(CPD) Day 2018 Keynote Address Once Upon a Time, Contrac

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4 Comparative Law and Constitutional Interpretation in Singapore: Insights from Constitutional Theory 114 ARUN K THIRUVENGADAM

Evolution of a Revolution Between 1965 and 2005, changes to Singapore’s Constitution were so tremendous as to amount to a revolution. These developments are comprehensively discussed and critically examined for the first time in this edited volume. With its momentous secession from the Federation of Malaysia in 1965, Singapore had the perfect opportunity to craft a popularly-endorsed constitution. Instead, it retained the 1958 State Constitution and augmented it with provisions from the Malaysian Federal Constitution. The decision in favour of stability and gradual change belied the revolutionary changes to Singapore’s Constitution over the next 40 years, transforming its erstwhile Westminster-style constitution into something quite unique. The Government’s overriding concern with ensuring stability, public order, Asian values and communitarian politics, are not without their setbacks or critics. This collection strives to enrich our understanding of the historical antecedents of the current Constitution and offers a timely retrospective assessment of how history, politics and economics have shaped the Constitution. It is the first collaborative effort by a group of Singapore constitutional law scholars and will be of interest to students and academics from a range of disciplines, including comparative constitutional law, political science, government and Asian studies. Dr Li-ann Thio is Professor of Law at the National University of Singapore where she teaches public international law, constitutional law and human rights law. She is a Nominated Member of Parliament (11th Session). Dr Kevin YL Tan is Director of Equilibrium Consulting Pte Ltd and Adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore where he teaches public law and media law. -

The Decline of Oral Advocacy Opportunities: Concerns and Implications

Published on 6 September 2018 THE DECLINE OF ORAL ADVOCACY OPPORTUNITIES: CONCERNS AND IMPLICATIONS [2018] SAL Prac 1 Singapore has produced a steady stream of illustrious and highly accomplished advocates over the decades. Without a doubt, these advocates have lifted and contributed to the prominence and reputation of the profession’s ability to deliver dispute resolution services of the highest quality. However, the conditions in which these advocates acquired, practised and honed their advocacy craft are very different from those present today. One trend stands out, in particular: the decline of oral advocacy opportunities across the profession as a whole. This is no trifling matter. The profession has a moral duty, if not a commercial imperative, to apply itself to addressing this phenomenon. Nicholas POON* LLB (Singapore Management University); Director, Breakpoint LLC; Advocate and Solicitor, Supreme Court of Singapore. I. Introduction 1 Effective oral advocacy is the bedrock of dispute resolution.1 It is also indisputable that effective oral advocacy is the product of training and experience. An effective advocate is forged in the charged atmosphere of courtrooms and arbitration chambers. An effective oral advocate does not become one by dint of age. 2 There is a common perception that sustained opportunities for oral advocacy in Singapore, especially for junior lawyers, are on the decline. This commentary suggests * This commentary reflects the author’s personal opinion. The author would like to thank the editors of the SAL Practitioner, as well as Thio Shen Yi SC and Paul Tan for reading through earlier drafts and offering their thoughtful insights. 1 Throughout this piece, any reference to “litigation” is a reference to contentious dispute resolution practice, including but not limited to court and arbitration proceedings, unless otherwise stated. -

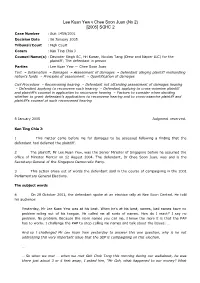

Lee Kuan Yew V Chee Soon Juan (No 2)

Lee Kuan Yew v Chee Soon Juan (No 2) [2005] SGHC 2 Case Number : Suit 1459/2001 Decision Date : 06 January 2005 Tribunal/Court : High Court Coram : Kan Ting Chiu J Counsel Name(s) : Davinder Singh SC, Hri Kumar, Nicolas Tang (Drew and Napier LLC) for the plaintiff; The defendant in person Parties : Lee Kuan Yew — Chee Soon Juan Tort – Defamation – Damages – Assessment of damages – Defendant alleging plaintiff mishandling nation's funds – Principles of assessment – Quantification of damages Civil Procedure – Reconvening hearing – Defendant not attending assessment of damages hearing – Defendant applying to reconvene such hearing – Defendant applying to cross-examine plaintiff and plaintiff's counsel in application to reconvene hearing – Factors to consider when deciding whether to grant defendant's applications to reconvene hearing and to cross-examine plaintiff and plaintiff's counsel at such reconvened hearing 6 January 2005 Judgment reserved. Kan Ting Chiu J: 1 This matter came before me for damages to be assessed following a finding that the defendant had defamed the plaintiff. 2 The plaintiff, Mr Lee Kuan Yew, was the Senior Minister of Singapore before he assumed the office of Minister Mentor on 12 August 2004. The defendant, Dr Chee Soon Juan, was and is the Secretary-General of the Singapore Democratic Party. 3 This action arose out of words the defendant said in the course of campaigning in the 2001 Parliamentary General Elections. The subject words 4 On 28 October 2001, the defendant spoke at an election rally at Nee Soon Central. He told his audience: Yesterday, Mr Lee Kuan Yew was at his best. -

Valedictory Reference in Honour of Justice Chao Hick Tin 27 September 2017 Address by the Honourable the Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon

VALEDICTORY REFERENCE IN HONOUR OF JUSTICE CHAO HICK TIN 27 SEPTEMBER 2017 ADDRESS BY THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE SUNDARESH MENON -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon Deputy Prime Minister Teo, Minister Shanmugam, Prof Jayakumar, Mr Attorney, Mr Vijayendran, Mr Hoong, Ladies and Gentlemen, 1. Welcome to this Valedictory Reference for Justice Chao Hick Tin. The Reference is a formal sitting of the full bench of the Supreme Court to mark an event of special significance. In Singapore, it is customarily done to welcome a new Chief Justice. For many years we have not observed the tradition of having a Reference to salute a colleague leaving the Bench. Indeed, the last such Reference I can recall was the one for Chief Justice Wee Chong Jin, which happened on this very day, the 27th day of September, exactly 27 years ago. In that sense, this is an unusual event and hence I thought I would begin the proceedings by saying something about why we thought it would be appropriate to convene a Reference on this occasion. The answer begins with the unique character of the man we have gathered to honour. 1 2. Much can and will be said about this in the course of the next hour or so, but I would like to narrate a story that took place a little over a year ago. It was on the occasion of the annual dinner between members of the Judiciary and the Forum of Senior Counsel. Mr Chelva Rajah SC was seated next to me and we were discussing the recently established Judicial College and its aspiration to provide, among other things, induction and continuing training for Judges. -

![Jeyaretnam Joshua Benjamin V Lee Kuan Yew [2001]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8008/jeyaretnam-joshua-benjamin-v-lee-kuan-yew-2001-1248008.webp)

Jeyaretnam Joshua Benjamin V Lee Kuan Yew [2001]

Jeyaretnam Joshua Benjamin v Lee Kuan Yew [2001] SGCA 55 Case Number : CA 600023/2001 Decision Date : 22 August 2001 Tribunal/Court : Court of Appeal Coram : Chao Hick Tin JA; L P Thean JA Counsel Name(s) : Appellant in person; Davinder Singh SC and Hri Kumar (Drew & Napier LLC) for the respondent Parties : Jeyaretnam Joshua Benjamin — Lee Kuan Yew Civil Procedure – Striking out – Dismissal of action for want of prosecution – Principles applicable – Inordinate and inexcusable delay – Respondent's delay of over two years without reason or explanation – Whether delay amounts to intentional and contumelious default – Prejudice by reason of delay – Whether unavailability of services of particular Queen's Counsel amounts to prejudice – Whether inordinate and inexcusable delay amounts to abuse of court process – Limitation period yet to expire – Whether action should be struck out Statutory Interpretation – Statutes – Repealing – Repeal of Rules of Court O 3 r 5 – Effect of repeal – Distinction between substantive and procedural rights – Whether amendments to procedural rules affect rights of parties retrospectively – Whether rights under repealed order survive – s 16(1)(c) Interpretation Act (Cap 1, 1999 Ed) Words and Phrases – 'Contumelious conduct' (delivering the judgment of the court): Introduction This appeal arose from an application by Mr Joshua Benjamin Jeyaretnam, the appellant (`the appellant`), to strike out the action in Suit 224/97 initiated by Mr Lee Kuan Yew, the respondent (`the respondent`). The application was heard before the senior assistant registrar and was dismissed. The appellant appealed to a judge-in-chambers, and the appeal was heard before Lai Siu Chiu J. The judge dismissed it and against her decision the appellant now brings this appeal. -

Lawlink 2019 Contents Contents

law link FROM ACADEMIA TO POLITICS AND BACK PROFESSOR S JAYAKUMAR ‘63 CHARTING THE NEXT CHAPTER JUSTICE ANDREW PHANG ‘82 ON LANGUAGE, LAW AND CODING STEPHANIE LAW ‘14 AN EMINENT CAREER EMERITUS PROFESSOR M. SORNARAJAH AI & THE LAW ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR DANIEL SENG ‘92 THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE FACULTY OF LAW LAWLINK 2019 CONTENTS CONTENTS 02 04 10 16 22 28 Dean’s Diary Alumni Spotlight Student Features Reunions Benefactors Law School Message from the Dean Professor S Jayakumar ’63: Highlights Congratulations Class of 2019 16 Class of 1989 22 From Academia to Politics and Back 03 Michael Hwang SC Class of 1999 24 An Eminent Career 10 30 Justice Andrew Phang ’82: Emeritus Professor M. Sornarajah Delivers SLR Annual Lecture 17 Charting The Next Chapter 05 Class of 2009 25 NUS Giving The Appeal of the Moot 18 AI & the Law 11 Stephanie Law ’14: LLM Class of 2009 26 Chandran Mohan K Nair ‘76 Associate Professor Daniel Seng ’92 & Susan de Silva ‘83: On Language, Law and Coding 08 Rag & Flag 2019 20 12 Scholarship to expand Kuala Lumpur & New York 27 Key Lectures minsets about success Law Alumni Mentor Programme Law IV: Unjust Enrichment 21 14 2019 09 Book Launches Alumni Relations & Development NUS Law Eu Tong Sen Building 469G Bukit Timah Road Singapore 259776 Tel: (65) 6516 3616 Fax: (65) 6779 0979 Email: [email protected] www.nuslawlink.com www.law.nus.edu.sg/alumni Please update your particulars at: www.law.nus.edu.sg/ alumni_update_particulars.asp 1 LAWLINK 2019 ALUMNI SPOTLIGHT DEAN’S DIARY FROM ACADEMIA TO POLITICS PROFESSOR SIMON CHESTERMAN AND BACK History often makes more sense in retrospect (TRAIL). -

Download This Case As A

CSJ‐ 08 ‐ 0006.0 Settle or fight? Far Eastern Economic Review and Singapore In the summer of 2006, Hugo Restall—editor-in-chief of the monthly Far Eastern Economic Review (FEER)--published an article about a marginalized member of the political opposition in Singapore. The piece asserted that the Singapore government had a remarkable record of winning libel suits, which suggested a deliberate effort to neutralize opponents and subdue the press. Restall hypothesized that instances of corruption were going unreported because the incentive to investigate them was outweighed by the threat of an unwinnable libel suit. Singapore’s ruling family reacted swiftly. Lawyers for Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong and his father Lee Kuan Yew, the founder of modern Singapore, asserted that the article amounted to an accusation against their clients of personal incompetence and corruption. In a series of letters, the Lees’ counsel demanded a printed apology, removal of the offending article from FEER’s website, and compensation for damages. The magazine maintained that Restall’s piece was not libelous; nonetheless, it offered to take mitigating action short of the three demands. But the Lees remained adamant. Then, in a move whose timing defied coincidence, the government Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts informed FEER that henceforth it would be subject to new, and onerous, regulations. These actions were not without precedent. Singapore was an authoritarian, if prosperous, country. The Lee family--which claimed that the country’s ruling precepts were rooted in Confucianism, a philosophy that vested power in an enlightened ruler—tolerated no criticism. The Lees had been in charge for decades. -

Pacific Century Regional Development Ltd V Canadian

Pacific Century Regional Development Ltd v Canadian Imperial Investment Pte Ltd [2001] SGCA 21 Case Number : CA 130/2000, 133/2000 Decision Date : 06 April 2001 Tribunal/Court : Court of Appeal Coram : Chao Hick Tin JA; L P Thean JA; Yong Pung How CJ Counsel Name(s) : Kasiviswanathan Shanmugam SC, Edwin Tong with Prakash Pillai and Vikhna Raj (Allen & Gledhill) for the appellant in CA 130/2000 and respondent in CA 133/2000; Davinder Singh SC with Hri Kumar and Siraj Omar (Drew & Napier) for the respondent in CA 130/2000 and appellant in CA 133/2000 Parties : Pacific Century Regional Development Ltd — Canadian Imperial Investment Pte Ltd Contract – Contractual terms – Rules of construction – Evidence on factual matrix – Scope of "factual matrix" – Admissibility of evidence of previous negotiations of parties and their declarations of subjective intent Contract – Contractual terms – Rules of construction – Whether "tag-along" clause applicable in circumstances of case – Regard to substance of transactions (delivering the judgment of the court): This appeal concerns the interpretation of a `tag-along` clause in a Shareholders` Agreement between the appellant and the predecessor company of the respondent, Orient Freedom Property Ltd (`OFPL`). The appellant, Pacific Century Regional Development (`PCRD`), is a public company listed on the Stock Exchange of Singapore. PCRD is a subsidiary of Pacific Century Group Holding Ltd (`PCG`) of Hong Kong. PCG is a company incorporated in the British Virgin Islands. Both PCRD and PCG are controlled by one Mr Richard Li (`Mr Li`) of Hong Kong. The respondent, Canadian Imperial Investment Pte Ltd (`CIIP`) is a Canadian company. -

ADVISORY BOARD MEETING MAY 11 and 12, 2016

BEST LAWYERS ADVISORY BOARD MEETING MAY 11 and 12, 2016 Bringing together the distinguished members of the Best Lawyers Advisory Board for discussions about management of law firms and in-house legal departments. elcome to the 2016 Best Lawyers Advisory WBoard Meeting. We are so pleased you are able to join us for the gathering of this unique group of the world’s preeminent law firm leaders and general counsel—a complete membership list appears in this brochure. For those arriving early May 11, Best Lawyers has organized a special viewing of Sylvia by the American Ballet Theatre at the Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center. This showing of Sylvia will feature company leads Isabella Boylston, Alban Lendorf, and Danill Simkin. The performance will be preceded by a discussion about the ballet and followed by a backstage tour of the opera house. The same evening, Best Lawyers will host a dinner where board members can see old friends and meet new ones. welcome The board meeting will take place May 12 at the offices of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. The meeting will focus on the challenges faced by law firm leaders and general counsel in our current economic climate. The meeting will feature a keynote address by Linda Klein, the incoming president of the American Bar Association, followed by a panel discussion chaired by former ABA president Carolyn Lamm on the globalization of the market for legal services and the impact of lawyer regulation worldwide. It is my pleasure to host this distinguished group, and I hope you enjoy the meeting. -

Chan Sek Keong the Accidental Lawyer

December 2012 ISSN: 0219-6441 Chan Sek Keong The Accidental Lawyer Against All Odds Interview with Nicholas Aw Be The Change Sustainable Development from Scraps THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE FACULTY OF LAW Contents DEAN’S MESSAGE A law school, more so than most professional schools at a university, is people. We have no laboratories; our research does not depend on expensive equipment. In our classes we use our share of information technology, but the primary means of instruction is the interaction between individuals. This includes teacher and student interaction, of course, but as we expand our project- based and clinical education programmes, it also includes student-student and student-client interactions. 03 Message From The Dean MESSAGE FROM The reputation of a law school depends, almost entirely, on the reputation of its people — its faculty LAW SCHOOL HIGHLIGHTS THE DEAN and staff, its students, and its alumni — and their 05 Benefactors impact on the world. 06 Class Action As a result of the efforts of all these people, NUS 07 NUS Law in the World’s Top Ten Schools Law has risen through the ranks of our peer law 08 NUS Law Establishes Centre for Asian Legal Studies schools to consolidate our reputation as Asia’s leading law school, ranked by London’s QS Rankings as the 10 th p12 09 Asian Law Institute Conference 10 NUS Law Alumni Mentor Programme best in the world. 11 Scholarships in Honour of Singapore’s First CJ Let me share with you just a few examples of some of the achievements this year by our faculty, our a LAWMNUS FEATURES students, and our alumni. -

Dinner Hosted by the Judiciary for the Forum of Senior Counsel

DINNER HOSTED BY THE JUDICIARY FOR THE FORUM OF SENIOR COUNSEL FRIDAY, 14 MAY 2010 REMARKS BY CHIEF JUSTICE CHAN SEK KEONG Ladies and Gentlemen: My colleagues and I warmly welcome you to tonight’s dinner, the second that the Judiciary is hosting for the Forum of Senior Counsel. In particular, I would welcome my predecessor as AG, Mr Tan Boon Teik who, instead of relaxing at home, has taken the trouble to join us tonight. The presence of so many Judges of the Supreme Court and Senior Counsel augurs well for this annual series of dinners evolving into a tradition that will continue to strengthen the bonds between the Bar and the Judiciary. 2. This dinner is not meant to be an occasion for long boring speeches, so I will keep my remarks short and make only three points. First, the Institute of Legal Education is in the process of developing a framework for Continuing Professional Development (CPD) in Singapore. Justice V K Rajah and his committee have been working very hard to set up a CPD programme that will be effective and meaningful to the Bar. It will be a serious programme, under which we will drag unwilling horses to the trough to drink. But we hope that the CPD programme will provide a true learning experience and not be a wasteful imposition on the Bar. It will be a great achievement if members of the Bar welcome this programme and not dismiss it as being a PR exercise. 2 3. When the CPD programme is finalised, we will need Senior Counsel and leading members of the corporate Bar to become lecturers, instructors and mentors. -

Appendix C Description of Judicial Institutions 87 and Stakeholders

38779 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public SectorPublic Governance DIRECTIONS INDEVELOPMENT Framework, Strategies, andLessons Judiciary-Led Reforms in Judiciary-Led Reforms Singapore Waleed HaiderMalik Waleed Judiciary-Led Reforms in Singapore Judiciary-Led Reforms in Singapore Framework, Strategies, and Lessons Waleed Haider Malik ©2007 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org E-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved 1 2 3 4 5 10 09 08 07 This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgement on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA; telephone: 978-750-8400; fax: 978-750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com.