Download This Case As A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tan Wah Piow, Smokescreens & Mirrors: Tracing the “Marxist

ASIATIC, VOLUME 7, NUMBER 1, JUNE 2013 Tan Wah Piow, Smokescreens & Mirrors: Tracing the “Marxist Conspiracy.” Singapore: Function 8 Limited, 2012. 172 pp. ISBN 978-981-07-2104-6. On May 21, 1987, in an operation code named “Spectrum,” Singapore’s Internal Security Department (ISD) detained 16 Singaporeans under the International Security Act (ISA). Six more people were arrested the very next month. The government accused these 22-English educated Singaporeans of being involved in a Marxist plot under the leadership of Tan Wah Piow, a self- styled Maoist, and a dissident Singaporean student leader living in the United Kingdom (UK). He was released from prison in 1976 after serving out a jail term of two years for rioting. As soon as he was released from jail, Tan Wah Piow was served with the call-up notice for National Service (NS), which is compulsory for all male Singapore citizens of 18 years and above. But instead of joining the NS, he fled to the UK in 1976, and sought and given political asylum. He has remained there ever since and is now a British citizen. On 26 May, 1987, Singapore’s Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) released a 41-page press statement justifying the detention without trial of the original 16. They were accused of knowing Catholic Church social worker Vincent Cheng, who in turn was alleged to be receiving orders from Tan Wah Piow to organise a network of young people who were inclined towards Marxism, with the objective of capturing political power after Lee Kuan Yew was no longer the prime minister (Lai To 205). -

Singapore's Chinese-Speaking and Their Perspectives on Merger

Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies, Volume 5, 2011-12 南方華裔研究雜志, 第五卷, 2011-12 “Flesh and Bone Reunite as One Body”: Singapore’s Chinese- speaking and their Perspectives on Merger ©2012 Thum Ping Tjin* Abstract Singapore’s Chinese speakers played the determining role in Singapore’s merger with the Federation. Yet the historiography is silent on their perspectives, values, and assumptions. Using contemporary Chinese- language sources, this article argues that in approaching merger, the Chinese were chiefly concerned with livelihoods, education, and citizenship rights; saw themselves as deserving of an equal place in Malaya; conceived of a new, distinctive, multiethnic Malayan identity; and rejected communist ideology. Meanwhile, the leaders of UMNO were intent on preserving their electoral dominance and the special position of Malays in the Federation. Finally, the leaders of the PAP were desperate to retain power and needed the Federation to remove their political opponents. The interaction of these three factors explains the shape, structure, and timing of merger. This article also sheds light on the ambiguity inherent in the transfer of power and the difficulties of national identity formation in a multiethnic state. Keywords: Chinese-language politics in Singapore; History of Malaya; the merger of Singapore and the Federation of Malaya; Decolonisation Introduction Singapore’s merger with the Federation of Malaya is one of the most pivotal events in the country’s history. This process was determined by the ballot box – two general elections, two by-elections, and a referendum on merger in four years. The centrality of the vote to this process meant that Singapore’s Chinese-speaking1 residents, as the vast majority of the colony’s residents, played the determining role. -

Institutionalized Leadership: Resilient Hegemonic Party Autocracy in Singapore

Institutionalized Leadership: Resilient Hegemonic Party Autocracy in Singapore By Netina Tan PhD Candidate Political Science Department University of British Columbia Paper prepared for presentation at CPSA Conference, 28 May 2009 Ottawa, Ontario Work- in-progress, please do not cite without author’s permission. All comments welcomed, please contact author at [email protected] Abstract In the age of democracy, the resilience of Singapore’s hegemonic party autocracy is puzzling. The People’s Action Party (PAP) has defied the “third wave”, withstood economic crises and ruled uninterrupted for more than five decades. Will the PAP remain a deviant case and survive the passing of its founding leader, Lee Kuan Yew? Building on an emerging scholarship on electoral authoritarianism and the concept of institutionalization, this paper argues that the resilience of hegemonic party autocracy depends more on institutions than coercion, charisma or ideological commitment. Institutionalized parties in electoral autocracies have a greater chance of survival, just like those in electoral democracies. With an institutionalized leadership succession system to ensure self-renewal and elite cohesion, this paper contends that PAP will continue to rule Singapore in the post-Lee era. 2 “All parties must institutionalize to a certain extent in order to survive” Angelo Panebianco (1988, 54) Introduction In the age of democracy, the resilience of Singapore’s hegemonic party regime1 is puzzling (Haas 1999). A small island with less than 4.6 million population, Singapore is the wealthiest non-oil producing country in the world that is not a democracy.2 Despite its affluence and ideal socio- economic prerequisites for democracy, the country has been under the rule of one party, the People’s Action Party (PAP) for the last five decades. -

The King's Nation: a Study of the Emergence and Development of Nation and Nationalism in Thailand

THE KING’S NATION: A STUDY OF THE EMERGENCE AND DEVELOPMENT OF NATION AND NATIONALISM IN THAILAND Andreas Sturm Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London (London School of Economics and Political Science) 2006 UMI Number: U215429 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U215429 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I Declaration I hereby declare that the thesis, submitted in partial fulfillment o f the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and entitled ‘The King’s Nation: A Study of the Emergence and Development of Nation and Nationalism in Thailand’, represents my own work and has not been previously submitted to this or any other institution for any degree, diploma or other qualification. Andreas Sturm 2 VV Abstract This thesis presents an overview over the history of the concepts ofnation and nationalism in Thailand. Based on the ethno-symbolist approach to the study of nationalism, this thesis proposes to see the Thai nation as a result of a long process, reflecting the three-phases-model (ethnie , pre-modem and modem nation) for the potential development of a nation as outlined by Anthony Smith. -

4 Comparative Law and Constitutional Interpretation in Singapore: Insights from Constitutional Theory 114 ARUN K THIRUVENGADAM

Evolution of a Revolution Between 1965 and 2005, changes to Singapore’s Constitution were so tremendous as to amount to a revolution. These developments are comprehensively discussed and critically examined for the first time in this edited volume. With its momentous secession from the Federation of Malaysia in 1965, Singapore had the perfect opportunity to craft a popularly-endorsed constitution. Instead, it retained the 1958 State Constitution and augmented it with provisions from the Malaysian Federal Constitution. The decision in favour of stability and gradual change belied the revolutionary changes to Singapore’s Constitution over the next 40 years, transforming its erstwhile Westminster-style constitution into something quite unique. The Government’s overriding concern with ensuring stability, public order, Asian values and communitarian politics, are not without their setbacks or critics. This collection strives to enrich our understanding of the historical antecedents of the current Constitution and offers a timely retrospective assessment of how history, politics and economics have shaped the Constitution. It is the first collaborative effort by a group of Singapore constitutional law scholars and will be of interest to students and academics from a range of disciplines, including comparative constitutional law, political science, government and Asian studies. Dr Li-ann Thio is Professor of Law at the National University of Singapore where she teaches public international law, constitutional law and human rights law. She is a Nominated Member of Parliament (11th Session). Dr Kevin YL Tan is Director of Equilibrium Consulting Pte Ltd and Adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore where he teaches public law and media law. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)“ . If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in “sectioning" the material. It is customary tc begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from “ photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

MARUAH Singapore

J U N E 2012 DEFINED MARUAH FROM THE PRESIDENT’S DESK ignity is starving. It needs detainees to varying grades of Dattention. It needs activation. inhuman treatment. Dignity is inherent in the human In this inaugural issue of condition. We all want to live Dignity Defined, MARUAH’s e-news every day in dignity, with dignity magazine, we raise awareness on and hopefully also treat others human rights, human responsibilities with dignity. The challenge to and social justice through discussions realising dignity lies in the around Operation Spectrum. difficulty of conceptualising this I was a teacher when the quality. alleged Marxist Conspiracy broke Dignity - what does it entail, in 1987. I read the newspapers what values does it embody, intently and watched television what principles is it based on, hawkishly as the detentions and how do we hold it in the palm were unravelled. I unpicked and of our hands to own it. We at unpacked the presentations made MARUAH are committed to finding by the government, the Catholic WHAT’S INSIDE? some answers to visualising, Church and the detainees too when conceptualising and discussing they were paraded for television 3 From History.... Dignity. We believe that much confessions. Operation Spectrum of what we can do to activate I was sceptical then and today & the ISA on Dignity comes from a rights- I am still unconvinced that they Rizwan Ahmad based approach to self and to were a national threat. others. As such we premise much It was an awful time. I watched 4 The Internal Security of our work on the aspirations the 22 detainees being ferried Act and the “Marxist of the Universal Declaration of away, from view. -

The Decline of Oral Advocacy Opportunities: Concerns and Implications

Published on 6 September 2018 THE DECLINE OF ORAL ADVOCACY OPPORTUNITIES: CONCERNS AND IMPLICATIONS [2018] SAL Prac 1 Singapore has produced a steady stream of illustrious and highly accomplished advocates over the decades. Without a doubt, these advocates have lifted and contributed to the prominence and reputation of the profession’s ability to deliver dispute resolution services of the highest quality. However, the conditions in which these advocates acquired, practised and honed their advocacy craft are very different from those present today. One trend stands out, in particular: the decline of oral advocacy opportunities across the profession as a whole. This is no trifling matter. The profession has a moral duty, if not a commercial imperative, to apply itself to addressing this phenomenon. Nicholas POON* LLB (Singapore Management University); Director, Breakpoint LLC; Advocate and Solicitor, Supreme Court of Singapore. I. Introduction 1 Effective oral advocacy is the bedrock of dispute resolution.1 It is also indisputable that effective oral advocacy is the product of training and experience. An effective advocate is forged in the charged atmosphere of courtrooms and arbitration chambers. An effective oral advocate does not become one by dint of age. 2 There is a common perception that sustained opportunities for oral advocacy in Singapore, especially for junior lawyers, are on the decline. This commentary suggests * This commentary reflects the author’s personal opinion. The author would like to thank the editors of the SAL Practitioner, as well as Thio Shen Yi SC and Paul Tan for reading through earlier drafts and offering their thoughtful insights. 1 Throughout this piece, any reference to “litigation” is a reference to contentious dispute resolution practice, including but not limited to court and arbitration proceedings, unless otherwise stated. -

Lee Kuan Yew Continue to flow As Life Returns to Normal at a Market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, Three Days After the State Funeral Service

TODAYONLINE.COM WE SET YOU THINKING SUNDAY, 5 APRIL 2015 SPECIAL EDITION MCI (P) 088/09/2014 The tributes to the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew continue to flow as life returns to normal at a market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, three days after the State Funeral Service. PHOTO: WEE TECK HIAN REMEMBERING MR LEE KUAN YEW SPECIAL ISSUE 2 REMEMBERING LEE KUAN YEW Tribute cards for the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew by the PCF Sparkletots Preschool (Bukit Gombak Branch) teachers and students displayed at the Chua Chu Kang tribute centre. PHOTO: KOH MUI FONG COMMENTARY Where does Singapore go from here? died a few hours earlier, he said: “I am for some, more bearable. Servicemen the funeral of a loved one can tell you, CARL SKADIAN grieved beyond words at the passing of and other volunteers went about their the hardest part comes next, when the DEPUTY EDITOR Mr Lee Kuan Yew. I know that we all duties quietly, eiciently, even as oi- frenzy of activity that has kept the mind feel the same way.” cials worked to revise plans that had busy is over. I think the Prime Minister expected to be adjusted after their irst contact Alone, without the necessary and his past week, things have been, many Singaporeans to mourn the loss, with a grieving nation. fortifying distractions of a period of T how shall we say … diferent but even he must have been surprised Last Sunday, about 100,000 people mourning in the company of others, in Singapore. by just how many did. -

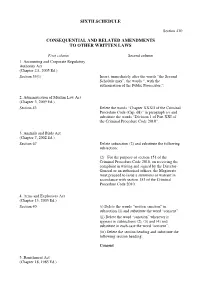

Sixth Schedule Consequential and Related

SIXTH SCHEDULE Section 430 CONSEQUENTIAL AND RELATED AMENDMENTS TO OTHER WRITTEN LAWS First column Second column 1. Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority Act (Chapter 2A, 2005 Ed.) Section 33(1) Insert, immediately after the words “the Second Schedule may”, the words “, with the authorisation of the Public Prosecutor,”. 2. Administration of Muslim Law Act (Chapter 3, 2009 Ed.) Section 43 Delete the words “Chapter XXXII of the Criminal Procedure Code (Cap. 68)” in paragraph ( e) and substitute the words “Division 1 of Part XXI of the Criminal Procedure Code 2010”. 3. Animals and Birds Act (Chapter 7, 2002 Ed.) Section 67 Delete subsection (2) and substitute the following subsection: (2) For the purpose of section 151 of the Criminal Procedure Code 2010, on receiving the complaint in writing and signed by the Director- General or an authorised officer, the Magistrate must proceed to issue a summons or warrant in accordance with section 153 of the Criminal Procedure Code 2010. 4. Arms and Explosives Act (Chapter 13, 2003 Ed.) Section 40 (i) Delete the words “written sanction” in subsection (1) and substitute the word “consent”. (ii) Delete the word “sanction” wherever it appears in subsections (2), (3) and (4) and substitute in each case the word “consent”. (iii) Delete the section heading and substitute the following section heading: Consent 5. Banishment Act (Chapter 18, 1985 Ed.) Section 8(4) (i) Delete the words “section 43 of the Criminal Procedure Code” and substitute the words “section 116 of the Criminal Procedure Code 2010”. (ii) Delete the marginal reference “Cap. 68.”. 6. Banking Act (Chapter 19, 2008 Ed.) Section 73 (i) Delete the word “Attorney-General” and substitute the words “Public Prosecutor”. -

3668212B-95De-4Ea1-9934

THE STATUTES OF THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE CORRUPTION, DRUG TRAFFICKING AND OTHER SERIOUS CRIMES (CONFISCATION OF BENEFITS) ACT (CHAPTER 65A) (Original Enactment: Act 29 of 1992) REVISED EDITION 2000 (1st July 2000) Prepared and Published by THE LAW REVISION COMMISSION UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF THE REVISED EDITION OF THE LAWS ACT (CHAPTER 275) Informal Consolidation – version in force from 2/1/2021 CHAPTER 65A 2000 Ed. Corruption, Drug Trafficking and Other Serious Crimes (Confiscation of Benefits) Act ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I PRELIMINARY Section 1. Short title 2. Interpretation 2A. Meaning of “item subject to legal privilege” 3. Application 3A. Suspicious Transaction Reporting Office PART II CONFISCATION OF BENEFITS OF DRUG DEALING OR CRIMINAL CONDUCT 4. Confiscation orders 5. Confiscation orders for benefits derived from criminal conduct 5A. Confiscation order unaffected by confiscation order under Organised Crime Act 2015 6. Live video or live television links 7. Assessing benefits of drug dealing 8. Assessing benefits derived from criminal conduct 9. Statements relating to drug dealing or criminal conduct 10. Amount to be recovered under confiscation order 11. Interest on sums unpaid under confiscation order 12. Definition of principal terms used 13. Protection of rights of third party PART III ENFORCEMENT, ETC., OF CONFISCATION ORDERS 14. Application of procedure for enforcing fines 1 Informal Consolidation – version in force from 2/1/2021 Corruption, Drug Trafficking and Other Serious Crimes 2000 Ed. (Confiscation of Benefits) CAP. 65A 2 Section 15. Cases in which restraint orders and charging orders may be made 16. Restraint orders 17. Charging orders in respect of land, capital markets products, etc. -

Criminal Procedure Code (Chapter 68)

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE CODE (CHAPTER 68) (Original Enactment: Act 15 of 2010) REVISED EDITION 2012 (31st August 2012) An Act relating to criminal procedure. [2nd January 2011] PART I PRELIMINARY Short title 1. This Act may be cited as the Criminal Procedure Code and is generally referred to in this Act as this Code. Interpretation 2. —(1) In this Code, unless the context otherwise requires — ―advocate‖ means an advocate and solicitor lawfully entitled to practise criminal law in Singapore; ―arrestable offence‖ and ―arrestable case‖ mean, respectively, an offence for which and a case in which a police officer may ordinarily arrest without warrant according to the third column of the First Schedule or under any other written law; ―bailable offence‖ means an offence shown as bailable in the fifth column of the First Schedule or which is made bailable by any other written law, and ―non-bailable offence‖ means any offence other than a bailable offence; ―complaint‖ means any allegation made orally or in writing to a Magistrate with a view to his taking action under this Code that some person, whether known or unknown, has committed or is guilty of an offence; ―computer‖ has the same meaning as in the Computer Misuse and Cybersecurity Act (Cap. 50A); [Act 3 of 2013 wef 13/03/2013] ―court‖ means the Court of Appeal, the High Court, a District Court or a Magistrate’s Court, as the case may be, which exercises criminal jurisdiction; ―criminal record‖ means the record of any — (a) conviction in any court, or subordinate military court established under section 80 of the Singapore Armed Forces Act (Cap.