Lee Kuan Yew V Chee Soon Juan (No 2)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Are Gender Reforms Adopted in Singapore? Party Pragmatism and Electoral Incentives* Netina Tan

Why Are Gender Reforms Adopted in Singapore? Party Pragmatism and Electoral Incentives* Netina Tan Abstract In Singapore, the percentage of elected female politicians rose from 3.8 percent in 1984 to 22.5 percent after the 2015 general election. After years of exclusion, why were gender reforms adopted and how did they lead to more women in political office? Unlike South Korea and Taiwan, this paper shows that in Singapore party pragmatism rather than international diffusion of gender equality norms, feminist lobbying, or rival party pressures drove gender reforms. It is argued that the ruling People’s Action Party’s (PAP) strategic and electoral calculations to maintain hegemonic rule drove its policy u-turn to nominate an average of about 17.6 percent female candidates in the last three elections. Similar to the PAP’s bid to capture women voters in the 1959 elections, it had to alter its patriarchal, conservative image to appeal to the younger, progressive electorate in the 2000s. Additionally, Singapore’s electoral system that includes multi-member constituencies based on plurality party bloc vote rule also makes it easier to include women and diversify the party slate. But despite the strategic and electoral incentives, a gender gap remains. Drawing from a range of public opinion data, this paper explains why traditional gender stereotypes, biased social norms, and unequal family responsibilities may hold women back from full political participation. Keywords: gender reforms, party pragmatism, plurality party bloc vote, multi-member constituencies, ethnic quotas, PAP, Singapore DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5509/2016892369 ____________________ Netina Tan is an assistant professor of political science at McMaster University. -

![Goh Chok Tong V Chee Soon Juan [2003] SGHC 79](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6361/goh-chok-tong-v-chee-soon-juan-2003-sghc-79-156361.webp)

Goh Chok Tong V Chee Soon Juan [2003] SGHC 79

Goh Chok Tong v Chee Soon Juan [2003] SGHC 79 Case Number : Suit 1460/2001 Decision Date : 04 April 2003 Tribunal/Court : High Court Coram : MPH Rubin J Counsel Name(s) : Davinder Singh SC, Hri Kumar and Nicolas Tang (Drew & Napier LLC) for the plaintiff/respondent; Defendant/appellant in person Parties : Goh Chok Tong — Chee Soon Juan Civil Procedure – Pleadings – Defence – Particulars of defence of duress not pleaded – Effect on defendant's case Civil Procedure – Summary judgment – Whether to set aside summary judgment and grant defendant leave to defend claim – Whether defendant had real or bona fide defence Contract – Discharge – Breach – Whether intimidation a defence to breach of contract of compromise Contract – Duress – Illegitimate pressure – Whether threat to enforce one's legal rights could amount to duress Tort – Defamation – Defamatory statements – Republication – Words republished by mass media – Whether defendant liable for republication Tort – Defamation – Defamatory statements – Whether defamatory in natural and ordinary meaning or by way of innuendo 1 This was an appeal by Dr Chee Soon Juan to judge-in-chambers from the decision of Senior Assistant Registrar Mr Toh Han Li (‘the SAR’) granting interlocutory judgment with damages (including aggravated damages) to be assessed in a defamation action brought by the respondent, Mr Goh Chok Tong. Mr Goh is, and was at all material times, the Prime Minister of the Republic of Singapore. On 25 October 2001, Mr Goh, as a candidate of the People’s Action Party (‘PAP’), was returned unopposed as a Member of Parliament for Marine Parade Group Representation Constituency (‘GRC’) in the 2001 General Elections. -

1 Singapore's Dominant Party System

Tan, Kenneth Paul (2017) “Singapore’s Dominant Party System”, in Governing Global-City Singapore: Legacies and Futures after Lee Kuan Yew, Routledge 1 Singapore’s dominant party system On the night of 11 September 2015, pundits, journalists, political bloggers, aca- demics, and others in Singapore’s chattering classes watched in long- drawn amazement as the media reported excitedly on the results of independent Singa- pore’s twelfth parliamentary elections that trickled in until the very early hours of the morning. It became increasingly clear as the night wore on, and any optimism for change wore off, that the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) had swept the votes in something of a landslide victory that would have puzzled even the PAP itself (Zakir, 2015). In the 2015 general elections (GE2015), the incumbent party won 69.9 per cent of the total votes (see Table 1.1). The Workers’ Party (WP), the leading opposition party that had five elected members in the previous parliament, lost their Punggol East seat in 2015 with 48.2 per cent of the votes cast in that single- member constituency (SMC). With 51 per cent of the votes, the WP was able to hold on to Aljunied, a five-member group representation constituency (GRC), by a very slim margin of less than 2 per cent. It was also able to hold on to Hougang SMC with a more convincing win of 57.7 per cent. However, it was undoubtedly a hard defeat for the opposition. The strong performance by the PAP bucked the trend observed since GE2001, when it had won 75.3 per cent of the total votes, the highest percent- age since independence. -

4 Comparative Law and Constitutional Interpretation in Singapore: Insights from Constitutional Theory 114 ARUN K THIRUVENGADAM

Evolution of a Revolution Between 1965 and 2005, changes to Singapore’s Constitution were so tremendous as to amount to a revolution. These developments are comprehensively discussed and critically examined for the first time in this edited volume. With its momentous secession from the Federation of Malaysia in 1965, Singapore had the perfect opportunity to craft a popularly-endorsed constitution. Instead, it retained the 1958 State Constitution and augmented it with provisions from the Malaysian Federal Constitution. The decision in favour of stability and gradual change belied the revolutionary changes to Singapore’s Constitution over the next 40 years, transforming its erstwhile Westminster-style constitution into something quite unique. The Government’s overriding concern with ensuring stability, public order, Asian values and communitarian politics, are not without their setbacks or critics. This collection strives to enrich our understanding of the historical antecedents of the current Constitution and offers a timely retrospective assessment of how history, politics and economics have shaped the Constitution. It is the first collaborative effort by a group of Singapore constitutional law scholars and will be of interest to students and academics from a range of disciplines, including comparative constitutional law, political science, government and Asian studies. Dr Li-ann Thio is Professor of Law at the National University of Singapore where she teaches public international law, constitutional law and human rights law. She is a Nominated Member of Parliament (11th Session). Dr Kevin YL Tan is Director of Equilibrium Consulting Pte Ltd and Adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore where he teaches public law and media law. -

![Lee Kuan Yew V Chee Soon Juan [2002]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8339/lee-kuan-yew-v-chee-soon-juan-2002-708339.webp)

Lee Kuan Yew V Chee Soon Juan [2002]

Lee Kuan Yew v Chee Soon Juan [2002] SGHC 122 Case Number : OM 600028/2002, OM 600029/2002 Decision Date : 07 June 2002 Tribunal/Court : High Court Coram : Lee Seiu Kin JC Counsel Name(s) : Chee Soon Juan in person; Jeffrey Chan and Leong Wing Tuck for the A-G chambers; Yang Lih Shyng (Khattar Wong & Partners) for the Law Society; Davinder Singh SC and Hri Kumar (Drew & Napier LLC) for the plaintiffs in the suits Parties : Lee Kuan Yew — Chee Soon Juan Judgment GROUNDS OF DECISION 1 The two Originating Motions before me concern applications by two Queen’s Counsel for ad hoc admission to practise as advocates and solicitors in the High Court. The applicant in O.M. 600028/2002 is Mr. Martin Lee Chu Ming, Q.C. and in O.M. 600029/2002, Mr. William Henric Nicholas, Q.C. They apply to be admitted to represent the defendant, Dr. Chee Soon Juan, in two actions in the High Court, viz. Suit No 1459/2001 in which the plaintiff is Mr. Lee Kuan Yew and Suit No 1460/2001 in which the plaintiff is Mr. Goh Chok Tong. Dr. Chee appeared before me to make the applications on behalf of Mr. Martin Lee and Mr. William Nicholas. 2 The applications are made under s 21 of the Legal Profession Act ("the Act") which provides as follows: (1) Notwithstanding anything to the contrary in this Act, the court may, for the purpose of any one case where the court is satisfied that it is of sufficient difficulty and complexity and having regard to the circumstances of the case, admit to practise as an advocate and solicitor any person who - (a) holds Her Majesty`s Patent as Queen`s Counsel; (b) does not ordinarily reside in Singapore or Malaysia but who has come or intends to come to Singapore for the purpose of appearing in the case; and (c) has special qualifications or experience for the purpose of the case. -

The Decline of Oral Advocacy Opportunities: Concerns and Implications

Published on 6 September 2018 THE DECLINE OF ORAL ADVOCACY OPPORTUNITIES: CONCERNS AND IMPLICATIONS [2018] SAL Prac 1 Singapore has produced a steady stream of illustrious and highly accomplished advocates over the decades. Without a doubt, these advocates have lifted and contributed to the prominence and reputation of the profession’s ability to deliver dispute resolution services of the highest quality. However, the conditions in which these advocates acquired, practised and honed their advocacy craft are very different from those present today. One trend stands out, in particular: the decline of oral advocacy opportunities across the profession as a whole. This is no trifling matter. The profession has a moral duty, if not a commercial imperative, to apply itself to addressing this phenomenon. Nicholas POON* LLB (Singapore Management University); Director, Breakpoint LLC; Advocate and Solicitor, Supreme Court of Singapore. I. Introduction 1 Effective oral advocacy is the bedrock of dispute resolution.1 It is also indisputable that effective oral advocacy is the product of training and experience. An effective advocate is forged in the charged atmosphere of courtrooms and arbitration chambers. An effective oral advocate does not become one by dint of age. 2 There is a common perception that sustained opportunities for oral advocacy in Singapore, especially for junior lawyers, are on the decline. This commentary suggests * This commentary reflects the author’s personal opinion. The author would like to thank the editors of the SAL Practitioner, as well as Thio Shen Yi SC and Paul Tan for reading through earlier drafts and offering their thoughtful insights. 1 Throughout this piece, any reference to “litigation” is a reference to contentious dispute resolution practice, including but not limited to court and arbitration proceedings, unless otherwise stated. -

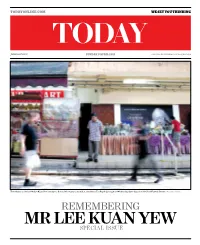

Lee Kuan Yew Continue to flow As Life Returns to Normal at a Market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, Three Days After the State Funeral Service

TODAYONLINE.COM WE SET YOU THINKING SUNDAY, 5 APRIL 2015 SPECIAL EDITION MCI (P) 088/09/2014 The tributes to the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew continue to flow as life returns to normal at a market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, three days after the State Funeral Service. PHOTO: WEE TECK HIAN REMEMBERING MR LEE KUAN YEW SPECIAL ISSUE 2 REMEMBERING LEE KUAN YEW Tribute cards for the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew by the PCF Sparkletots Preschool (Bukit Gombak Branch) teachers and students displayed at the Chua Chu Kang tribute centre. PHOTO: KOH MUI FONG COMMENTARY Where does Singapore go from here? died a few hours earlier, he said: “I am for some, more bearable. Servicemen the funeral of a loved one can tell you, CARL SKADIAN grieved beyond words at the passing of and other volunteers went about their the hardest part comes next, when the DEPUTY EDITOR Mr Lee Kuan Yew. I know that we all duties quietly, eiciently, even as oi- frenzy of activity that has kept the mind feel the same way.” cials worked to revise plans that had busy is over. I think the Prime Minister expected to be adjusted after their irst contact Alone, without the necessary and his past week, things have been, many Singaporeans to mourn the loss, with a grieving nation. fortifying distractions of a period of T how shall we say … diferent but even he must have been surprised Last Sunday, about 100,000 people mourning in the company of others, in Singapore. by just how many did. -

ASIAN REPRESENTATIONS of AUSTRALIA Alison Elizabeth Broinowski 12 December 2001 a Thesis Submitted for the Degree Of

ABOUT FACE: ASIAN REPRESENTATIONS OF AUSTRALIA Alison Elizabeth Broinowski 12 December 2001 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University ii Statement This thesis is my own work. Preliminary research was undertaken collaboratively with a team of Asian Australians under my co-direction with Dr Russell Trood and Deborah McNamara. They were asked in 1995-96 to collect relevant material, in English and vernacular languages, from the public sphere in their countries of origin. Three monographs based on this work were published in 1998 by the Centre for the Study of Australia Asia Relations at Griffith University and these, together with one unpublished paper, are extensively cited in Part 2. The researchers were Kwak Ki-Sung, Anne T. Nguyen, Ouyang Yu, and Heidi Powson and Lou Miles. Further research was conducted from 2000 at the National Library with a team of Chinese and Japanese linguists from the Australian National University, under an ARC project, ‘Asian Accounts of Australia’, of which Shun Ikeda and I are Chief Investigators. Its preliminary findings are cited in Part 2. Alison Broinowski iii Abstract This thesis considers the ways in which Australia has been publicly represented in ten Asian societies in the twentieth century. It shows how these representations are at odds with Australian opinion leaders’ assertions about being a multicultural society, with their claims about engagement with Asia, and with their understanding of what is ‘typically’ Australian. It reviews the emergence and development of Asian regionalism in the twentieth century, and considers how Occidentalist strategies have come to be used to exclude and marginalise Australia. -

Transcript of a Press Conference Given by the Prime Minister of Singapore, Mr. Lee Kuan Yew, at Broadcasting House, Singapore, A

1 TRANSCRIPT OF A PRESS CONFERENCE GIVEN BY THE PRIME MINISTER OF SINGAPORE, MR. LEE KUAN YEW, AT BROADCASTING HOUSE, SINGAPORE, AT 1200 HOURS ON MONDAY 9TH AUGUST, 1965. Question: Mr. Prime Minister, after these momentous pronouncements, what most of us of the foreign press would be interested to learn would be your attitude towards Indonesia, particularly in the context of Indonesian confrontation, and how you view to conduct relations with Indonesia in the future as an independent, sovereign nation. Mr. Lee: I would like to phrase it most carefully because this is a delicate matter. But I think I can express my attitude in this way: We want to be friends with Indonesia. We have always wanted to be friends with Indonesia. We would like to settle any difficulties and differences with Indonesia. But we must survive. We have a right to survive. And, to survive, we must be sure that we cannot be just overrun. You know, invaded by armies or knocked out by rockets, if they have rockets -- which they have, ground-to-air. I'm not sure whether they lky\1965\lky0809b.doc 2 have ground-to-ground missiles. And, what I think is also important is we want, in spite of all that has happened -- which I think were largely ideological differences between us and the former Central Government, between us and the Alliance Government -- we want to-operate with them, on the most fair and equal basis. The emphasis is co-operate. We need them to survive. Our water supply comes from Johore. Our trade, 20-odd per cent -- over 20 per cent; I think about 24 per cent -- with Malaya, and about 4 to 5 per cent with Sabah and Sarawak. -

One Party Dominance Survival: the Case of Singapore and Taiwan

One Party Dominance Survival: The Case of Singapore and Taiwan DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lan Hu Graduate Program in Political Science The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Professor R. William Liddle Professor Jeremy Wallace Professor Marcus Kurtz Copyrighted by Lan Hu 2011 Abstract Can a one-party-dominant authoritarian regime survive in a modernized society? Why is it that some survive while others fail? Singapore and Taiwan provide comparable cases to partially explain this puzzle. Both countries share many similar cultural and developmental backgrounds. One-party dominance in Taiwan failed in the 1980s when Taiwan became modern. But in Singapore, the one-party regime survived the opposition’s challenges in the 1960s and has remained stable since then. There are few comparative studies of these two countries. Through empirical studies of the two cases, I conclude that regime structure, i.e., clientelistic versus professional structure, affects the chances of authoritarian survival after the society becomes modern. This conclusion is derived from a two-country comparative study. Further research is necessary to test if the same conclusion can be applied to other cases. This research contributes to the understanding of one-party-dominant regimes in modernizing societies. ii Dedication Dedicated to the Lord, Jesus Christ. “Counsel and sound judgment are mine; I have insight, I have power. By Me kings reign and rulers issue decrees that are just; by Me princes govern, and nobles—all who rule on earth.” Proverbs 8:14-16 iii Acknowledgments I thank my committee members Professor R. -

Valedictory Reference in Honour of Justice Chao Hick Tin 27 September 2017 Address by the Honourable the Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon

VALEDICTORY REFERENCE IN HONOUR OF JUSTICE CHAO HICK TIN 27 SEPTEMBER 2017 ADDRESS BY THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE SUNDARESH MENON -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon Deputy Prime Minister Teo, Minister Shanmugam, Prof Jayakumar, Mr Attorney, Mr Vijayendran, Mr Hoong, Ladies and Gentlemen, 1. Welcome to this Valedictory Reference for Justice Chao Hick Tin. The Reference is a formal sitting of the full bench of the Supreme Court to mark an event of special significance. In Singapore, it is customarily done to welcome a new Chief Justice. For many years we have not observed the tradition of having a Reference to salute a colleague leaving the Bench. Indeed, the last such Reference I can recall was the one for Chief Justice Wee Chong Jin, which happened on this very day, the 27th day of September, exactly 27 years ago. In that sense, this is an unusual event and hence I thought I would begin the proceedings by saying something about why we thought it would be appropriate to convene a Reference on this occasion. The answer begins with the unique character of the man we have gathered to honour. 1 2. Much can and will be said about this in the course of the next hour or so, but I would like to narrate a story that took place a little over a year ago. It was on the occasion of the annual dinner between members of the Judiciary and the Forum of Senior Counsel. Mr Chelva Rajah SC was seated next to me and we were discussing the recently established Judicial College and its aspiration to provide, among other things, induction and continuing training for Judges. -

![Jeyaretnam Joshua Benjamin V Lee Kuan Yew [2001]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8008/jeyaretnam-joshua-benjamin-v-lee-kuan-yew-2001-1248008.webp)

Jeyaretnam Joshua Benjamin V Lee Kuan Yew [2001]

Jeyaretnam Joshua Benjamin v Lee Kuan Yew [2001] SGCA 55 Case Number : CA 600023/2001 Decision Date : 22 August 2001 Tribunal/Court : Court of Appeal Coram : Chao Hick Tin JA; L P Thean JA Counsel Name(s) : Appellant in person; Davinder Singh SC and Hri Kumar (Drew & Napier LLC) for the respondent Parties : Jeyaretnam Joshua Benjamin — Lee Kuan Yew Civil Procedure – Striking out – Dismissal of action for want of prosecution – Principles applicable – Inordinate and inexcusable delay – Respondent's delay of over two years without reason or explanation – Whether delay amounts to intentional and contumelious default – Prejudice by reason of delay – Whether unavailability of services of particular Queen's Counsel amounts to prejudice – Whether inordinate and inexcusable delay amounts to abuse of court process – Limitation period yet to expire – Whether action should be struck out Statutory Interpretation – Statutes – Repealing – Repeal of Rules of Court O 3 r 5 – Effect of repeal – Distinction between substantive and procedural rights – Whether amendments to procedural rules affect rights of parties retrospectively – Whether rights under repealed order survive – s 16(1)(c) Interpretation Act (Cap 1, 1999 Ed) Words and Phrases – 'Contumelious conduct' (delivering the judgment of the court): Introduction This appeal arose from an application by Mr Joshua Benjamin Jeyaretnam, the appellant (`the appellant`), to strike out the action in Suit 224/97 initiated by Mr Lee Kuan Yew, the respondent (`the respondent`). The application was heard before the senior assistant registrar and was dismissed. The appellant appealed to a judge-in-chambers, and the appeal was heard before Lai Siu Chiu J. The judge dismissed it and against her decision the appellant now brings this appeal.