The Decline of Oral Advocacy Opportunities: Concerns and Implications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bench & Bar Games 2007

South China Sea MALAYSIA SINGAPORE MALAYSIA | SINGAPORE Bench & Bar Games 2007 28 - 30 April 2007 Java Sea OFFICES SINGAPORE 80 RAFFLES PLACE #33-00 UOB PLAZA 1 SINGAPORE 048624 TEL: +65 6225 2626 FAX: +65 6225 1838 SHANGHAI UNIT 23-09 OCEAN TOWERS NO. 550 YAN AN EAST ROAD SHANGHAI 200001, CHINA TEL: +86 (21) 6322 9191 FAX: +86 (21) 6322 4550 EMAIL [email protected] CONTACT PERSON HELEN YEO, MANAGING PARTNER YEAR ESTABLISHED 1861 NUMBER OF LAWYERS 95 KEY PRACTICE AREAS CORPORATE FINANCE INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY & TECHNOLOGY LITIGATION & ARBITRATION REAL ESTATE LANGUAGES SPOKEN ENGLISH, MANDARIN, MALAY, TAMIL www.rodyk.com 1 Contents Message from The Honourable The Chief 2 10 Council Members of Bar Council Malaysia Justice, Singapore 2007/2008 Message from The Honourable Chief 3 15 Sports Committee - Singapore and Malaysia Justice, Malaysia Message from the President of The Law 4 16 Teams Society of Singapore Message from the President of Bar Council 5 Malaysia 22 Results of Past Games 1969 to 2006 Message from Chairman, Sports 6 Sports Suit No. 1 of 1969 Committee, The Law Society of Singapore 23 Message from Chairman, Sports 7 Acknowledgements Committee, Bar Council Malaysia 24 9 The Council of The Law Society of Singapore 2007 Malaysia | Singapore Bench & Bar Games 2007 022 Message from The Honourable The Chief Justice, Singapore The time of the year has arrived once again for the Malaysia/Singapore Bench & Bar Games. Last year we enjoyed the warm hospitality of our Malaysian hosts on the magical island of Langkawi and this year, we will do all that we can to reciprocate. -

OPENING of the LEGAL YEAR 2021 Speech by Attorney-General

OPENING OF THE LEGAL YEAR 2021 Speech by Attorney-General, Mr Lucien Wong, S.C. 11 January 2021 May it please Your Honours, Chief Justice, Justices of the Court of Appeal, Judges of the Appellate Division, Judges and Judicial Commissioners, Introduction 1. The past year has been an extremely trying one for the country, and no less for my Chambers. It has been a real test of our fortitude, our commitment to defend and advance Singapore’s interests, and our ability to adapt to unforeseen difficulties brought about by the COVID-19 virus. I am very proud of the good work my Chambers has done over the past year, which I will share with you in the course of my speech. I also acknowledge that the past year has shown that we have some room to grow and improve. I will outline the measures we have undertaken as an institution to address issues which we faced and ensure that we meet the highest standards of excellence, fairness and integrity in the years to come. 2. My speech this morning is in three parts. First, I will talk about the critical legal support which we provided to the Government throughout the COVID-19 crisis. Second, I will discuss some initiatives we have embarked on to future-proof the organisation and to deal with the challenges which we faced this past year, including digitalisation and workforce changes. Finally, I will share my reflections about the role we play in the criminal justice system and what I consider to be our grave and solemn duty as prosecutors. -

4 Comparative Law and Constitutional Interpretation in Singapore: Insights from Constitutional Theory 114 ARUN K THIRUVENGADAM

Evolution of a Revolution Between 1965 and 2005, changes to Singapore’s Constitution were so tremendous as to amount to a revolution. These developments are comprehensively discussed and critically examined for the first time in this edited volume. With its momentous secession from the Federation of Malaysia in 1965, Singapore had the perfect opportunity to craft a popularly-endorsed constitution. Instead, it retained the 1958 State Constitution and augmented it with provisions from the Malaysian Federal Constitution. The decision in favour of stability and gradual change belied the revolutionary changes to Singapore’s Constitution over the next 40 years, transforming its erstwhile Westminster-style constitution into something quite unique. The Government’s overriding concern with ensuring stability, public order, Asian values and communitarian politics, are not without their setbacks or critics. This collection strives to enrich our understanding of the historical antecedents of the current Constitution and offers a timely retrospective assessment of how history, politics and economics have shaped the Constitution. It is the first collaborative effort by a group of Singapore constitutional law scholars and will be of interest to students and academics from a range of disciplines, including comparative constitutional law, political science, government and Asian studies. Dr Li-ann Thio is Professor of Law at the National University of Singapore where she teaches public international law, constitutional law and human rights law. She is a Nominated Member of Parliament (11th Session). Dr Kevin YL Tan is Director of Equilibrium Consulting Pte Ltd and Adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore where he teaches public law and media law. -

Annual Report 2019 | 3 About the Academy

ANNUAL REPORT ACADEMY OF MEDICINE 2019 SINGAPORE Committed to specialist education and training since 1957 CONTENT ACADEMY OF MEDICINE, SINGAPORE The Academy 1 Master’s Message 2 The 2019-2020 Council 5 The Academy 5 Representation at Ministry of Health and Related Organisations 6 Year in Review 2019 7 Finance and Establishment Review Committee Events 8 Dinner & Dialogue with Senior Minister of State (Health) 9 AMS Chinese New Year Celebration 9 Formation of the Chapter of Pain Medicine Physicians 10 Induction Comitia 2019 10 Public Forum 2019 Sponsorships, Grants and Awards 11 Awards 11 Visiting Academicians 12 Visiting Lecturers 12 Travel Assistance 12 Letters of Support Deanery 13 In-Training Examinations 14 Diploma in Hospital Medicine 14 Mandatory Geriatric Medicine Modular Course 14 Master of Health Professionals Education, Singapore (MHPE-S) 14 2019 Intake (Unit One) and 2018 Intake (Unit Seven) 15 Self Learning Module (SLM) 15 CPD Bulletin 15 AMS Fellowship Training Programme 16 MOH Contract of Services for Healthcare Services 16 Dental Specialist Accreditation Assessment 16 Staff Registrar Scheme Office of Professional Affairs 18 Guidelines, Advisories & Consensus Committee (GACC) 21 Ad-Hoc OPA Activity – PDPA Awareness Talk 2019 21 Medical Experts Committee (MEC) 23 Faculty of Medical Experts (FME) Standing Committees 24 Membership 25 Joint Committee on Specialist Training 26 Publications Past Masters and Honorary Fellows List Our People 30 Staff List Finance Statements for the Financial Year Ended December 2019 COLLEGES AND -

4. Arbitration

(2012) 13 SAL Ann Rev Arbitration 59 4. ARBITRATION Lawrence BOO LLB (University of Singapore), LLM (National University of Singapore); FSIArb, FCIArb, FAMINZ, Chartered Arbitrator; Solicitor (England and Wales), Advocate and Solicitor (Singapore); Adjunct Professor, Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore; Adjunct Professor, Faculty of Law, Bond University (Australia); Visiting Professor, School of Law, Wuhan University (China). Recourse against awards – Domestic arbitration Institutional rules operating as “exclusion agreement” 4.1 An arbitral award made under the Arbitration Act (Cap 10, 2002 Rev Ed) (“AA”) may be appealed against on a question of law, upon notice to the other parties and to the arbitral tribunal. Such a right may nevertheless be excluded by agreement of the parties. The mere declaration by the parties that the award is intended to be “final and binding” is not of itself sufficient to constitute such an agreement: see Holland Leedon Pte Ltd v Metalform Asia Pte Ltd [2011] 1 SLR 517 at [5]. Adoption of the institutional rules which excludes an appeal to court without specific reservation has the effect of an exclusion agreement: Halsbury’s Laws of Singapore vol 1(2) (Singapore: LexisNexis, 2011 Reissue) at para 20.126. 4.2 In Daimler South East Asia Pte Ltd v Front Row Investment Holdings (Singapore) Pte Ltd [2012] 4 SLR 837, the parties entered into a joint venture agreement which provides for all disputes arising out of the said agreement to be finally settled under the International Chamber of Commerce (“ICC”) Rules of Arbitration 1998. Disputes arose and the plaintiff commenced arbitration to which the defendant lodged a counterclaim. -

Steep Rise Ltd V Attorney-General

Steep Rise Ltd v Attorney-General [2020] SGCA 20 Case Number : Civil Appeal No 30 of 2019 Decision Date : 24 March 2020 Tribunal/Court : Court of Appeal Coram : Tay Yong Kwang JA; Steven Chong JA; Woo Bih Li J Counsel Name(s) : Chan Tai-Hui, Jason SC, Tan Kai Liang, Daniel Seow Wei Jin, Victor Leong Hoi Seng and Lim Min Li Amanda (Allen & Gledhill LLP) for the appellant; Kristy Tan, Kenneth Wong, Ng Kexian and Tan Ee Kuan (Attorney-General's Chambers) for the respondent. Parties : Steep Rise Limited — Attorney-General Criminal Procedure and Sentencing – Mutual legal assistance – Duty of full and frank disclosure Criminal Procedure and Sentencing – Mutual legal assistance – Enforcement of foreign confiscation order – Risk of dissipation 24 March 2020 Tay Yong Kwang JA (delivering the grounds of decision of the court): Introduction 1 On 22 August 2017, a Restraint Order was made by the High Court on the application of the Attorney-General (“the AG”) pursuant to s 29 read with para 7(1) of the Third Schedule of the Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters Act (Cap 190A, 2001 Rev Ed) (“MACMA”), restraining any dealing with the funds in the bank account of Steep Rise Limited (“the appellant”) in the Bank of Singapore (“the BOS Account”). Subsequently, the appellant applied to the High Court to discharge the order of court. The High Court Judge (“the Judge”) dismissed the application and made no order as to costs as the AG did not seek an order for costs. 2 The appellant then appealed against the Judge’s decision. -

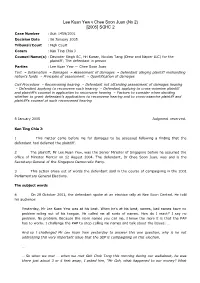

Lee Kuan Yew V Chee Soon Juan (No 2)

Lee Kuan Yew v Chee Soon Juan (No 2) [2005] SGHC 2 Case Number : Suit 1459/2001 Decision Date : 06 January 2005 Tribunal/Court : High Court Coram : Kan Ting Chiu J Counsel Name(s) : Davinder Singh SC, Hri Kumar, Nicolas Tang (Drew and Napier LLC) for the plaintiff; The defendant in person Parties : Lee Kuan Yew — Chee Soon Juan Tort – Defamation – Damages – Assessment of damages – Defendant alleging plaintiff mishandling nation's funds – Principles of assessment – Quantification of damages Civil Procedure – Reconvening hearing – Defendant not attending assessment of damages hearing – Defendant applying to reconvene such hearing – Defendant applying to cross-examine plaintiff and plaintiff's counsel in application to reconvene hearing – Factors to consider when deciding whether to grant defendant's applications to reconvene hearing and to cross-examine plaintiff and plaintiff's counsel at such reconvened hearing 6 January 2005 Judgment reserved. Kan Ting Chiu J: 1 This matter came before me for damages to be assessed following a finding that the defendant had defamed the plaintiff. 2 The plaintiff, Mr Lee Kuan Yew, was the Senior Minister of Singapore before he assumed the office of Minister Mentor on 12 August 2004. The defendant, Dr Chee Soon Juan, was and is the Secretary-General of the Singapore Democratic Party. 3 This action arose out of words the defendant said in the course of campaigning in the 2001 Parliamentary General Elections. The subject words 4 On 28 October 2001, the defendant spoke at an election rally at Nee Soon Central. He told his audience: Yesterday, Mr Lee Kuan Yew was at his best. -

![[2020] SGCA 108 Civil Appeal No 34 of 2019 Between (1) BRS … Appellant and (1) BRQ (2) BRR … Respondents in the Matter of Or](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0788/2020-sgca-108-civil-appeal-no-34-of-2019-between-1-brs-appellant-and-1-brq-2-brr-respondents-in-the-matter-of-or-970788.webp)

[2020] SGCA 108 Civil Appeal No 34 of 2019 Between (1) BRS … Appellant and (1) BRQ (2) BRR … Respondents in the Matter of Or

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE [2020] SGCA 108 Civil Appeal No 34 of 2019 Between (1) BRS … Appellant And (1) BRQ (2) BRR … Respondents In the matter of Originating Summons No 770 of 2018 Between (1) BRS … Plaintiff And (1) BRQ (2) BRR … Defendants Civil Appeal No 35 of 2019 Between (1) BRQ (2) BRR … Appellants And (1) BRS … Respondent In the matter of Originating Summons No 512 of 2018 Between (1) BRQ (2) BRR … Plaintiffs And (1) BRS (2) BRT … Defendants JUDGMENT [Arbitration] — [Award] — [Recourse against award] — [Setting aside] — [Whether three-month time limit extended by request for correction] [Arbitration] — [Award] — [Recourse against award] — [Setting aside] — [Breach of natural justice] TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION............................................................................................1 BACKGROUND FACTS ................................................................................2 THE PARTIES ...................................................................................................3 THE SPA.........................................................................................................3 THE BULK POWER TRANSMISSION AGREEMENT .............................................6 DELAYS IN THE PROJECT AND COST OVERRUN ...............................................6 THE ARBITRATION...........................................................................................7 Relief sought...............................................................................................8 -

Giving Report 2010/2011 Report Giving

Medicine Engineering Public Policy Music Business Law Arts and Social Sciences National University Singapore of GIVING REPORT 2010/2011 GIVING REPORT DEVELOPMENT OFFICE National University of Singapore Shaw Foundation Alumni House 2010/2011 #03-01, 11 Kent Ridge Drive Singapore 119244 t: +65 6516 8000 / 1-800-DEVELOP f: +65 6775 9161 e: [email protected] www.giving.nus.edu.sg PRESIDENT’S STATEMENT Dear alumni and friends, Your support this past year has provided countless opportunities for the National Science University of Singapore (NUS), particularly From music to for the students who are at the heart of our University. For example, approximately medicine, your 1,700 students received bursaries. Around 1,400 of these were partially supported by gift today makes the Annual Giving campaign and about 300 are Named Bursaries. Thank you for Computing a difference to a making this possible. student’s tomorrow Our future is very exciting. NUS University Town will open its doors in the coming months and the Yale-NUS College will follow a few years later. These new President’s Statement........................................... 01 initiatives will allow NUS to continue pursuing its goal of offering students, Thank You For Your Contribution.................... 02 from the entire NUS campus, a broader Education { 02 } education that will challenge them and Research { 06 } position them well for the future. Service { 10 } Design and Environment Through these and other innovations, Annual Giving – NUS is also breaking new ground in Making A Difference Together......................... 14 higher education, both in Singapore and the region. The NUS experience will Strength In Numbers............................................ -

Valedictory Reference in Honour of Justice Chao Hick Tin 27 September 2017 Address by the Honourable the Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon

VALEDICTORY REFERENCE IN HONOUR OF JUSTICE CHAO HICK TIN 27 SEPTEMBER 2017 ADDRESS BY THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE SUNDARESH MENON -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon Deputy Prime Minister Teo, Minister Shanmugam, Prof Jayakumar, Mr Attorney, Mr Vijayendran, Mr Hoong, Ladies and Gentlemen, 1. Welcome to this Valedictory Reference for Justice Chao Hick Tin. The Reference is a formal sitting of the full bench of the Supreme Court to mark an event of special significance. In Singapore, it is customarily done to welcome a new Chief Justice. For many years we have not observed the tradition of having a Reference to salute a colleague leaving the Bench. Indeed, the last such Reference I can recall was the one for Chief Justice Wee Chong Jin, which happened on this very day, the 27th day of September, exactly 27 years ago. In that sense, this is an unusual event and hence I thought I would begin the proceedings by saying something about why we thought it would be appropriate to convene a Reference on this occasion. The answer begins with the unique character of the man we have gathered to honour. 1 2. Much can and will be said about this in the course of the next hour or so, but I would like to narrate a story that took place a little over a year ago. It was on the occasion of the annual dinner between members of the Judiciary and the Forum of Senior Counsel. Mr Chelva Rajah SC was seated next to me and we were discussing the recently established Judicial College and its aspiration to provide, among other things, induction and continuing training for Judges. -

![Jeyaretnam Joshua Benjamin V Lee Kuan Yew [2001]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8008/jeyaretnam-joshua-benjamin-v-lee-kuan-yew-2001-1248008.webp)

Jeyaretnam Joshua Benjamin V Lee Kuan Yew [2001]

Jeyaretnam Joshua Benjamin v Lee Kuan Yew [2001] SGCA 55 Case Number : CA 600023/2001 Decision Date : 22 August 2001 Tribunal/Court : Court of Appeal Coram : Chao Hick Tin JA; L P Thean JA Counsel Name(s) : Appellant in person; Davinder Singh SC and Hri Kumar (Drew & Napier LLC) for the respondent Parties : Jeyaretnam Joshua Benjamin — Lee Kuan Yew Civil Procedure – Striking out – Dismissal of action for want of prosecution – Principles applicable – Inordinate and inexcusable delay – Respondent's delay of over two years without reason or explanation – Whether delay amounts to intentional and contumelious default – Prejudice by reason of delay – Whether unavailability of services of particular Queen's Counsel amounts to prejudice – Whether inordinate and inexcusable delay amounts to abuse of court process – Limitation period yet to expire – Whether action should be struck out Statutory Interpretation – Statutes – Repealing – Repeal of Rules of Court O 3 r 5 – Effect of repeal – Distinction between substantive and procedural rights – Whether amendments to procedural rules affect rights of parties retrospectively – Whether rights under repealed order survive – s 16(1)(c) Interpretation Act (Cap 1, 1999 Ed) Words and Phrases – 'Contumelious conduct' (delivering the judgment of the court): Introduction This appeal arose from an application by Mr Joshua Benjamin Jeyaretnam, the appellant (`the appellant`), to strike out the action in Suit 224/97 initiated by Mr Lee Kuan Yew, the respondent (`the respondent`). The application was heard before the senior assistant registrar and was dismissed. The appellant appealed to a judge-in-chambers, and the appeal was heard before Lai Siu Chiu J. The judge dismissed it and against her decision the appellant now brings this appeal. -

Market Surveillance & Compliance Panel Annual

MARKET SURVEILLANCE & COMPLIANCE PANEL ANNUAL REPORT 2017 IN MEMORIAM JOSEPH GRIMBERG SC It is with great sadness that we mark of the Middle Temple. Joe retained the approached to represent the Presidency. He the passing of Mr Joseph Grimberg on graciousness and bearing of the best accepted the brief with reluctance, claiming 17 August 2017. English barristers all his life. He spoke with that he had lost his nerve. His performance a refined and cultured English accent – a in court belied his modesty; those who had Mr Joe Grimberg was the first Chairman of natural one, not an artificial snobby stage the privilege of watching him in action can the Market Surveillance and Compliance accent put on to impress others. He was testify to the elegant eloquence with which Panel (MSCP). He took office on also a keen sportsman who played rugby he presented the case for the Presidency. 1 January 2003, right at the beginning when and cricket for the Singapore Cricket the Singapore wholesale electricity market Club, a reflection perhaps of his anglophile Joe was undoubtedly one of the very best was inaugurated. He served for five years character. advocates to grace our courts. His leading until 31 December 2007, at a time when the role in the legal profession was recognised fledgling market was just taking off. The role In 1956, Joe returned to Singapore where when he was appointed Senior Counsel in of the Chairman was crucial in those days he joined the firm in which he spent the bulk 1997, one of the first batch of local ‘silks’.