MOUNT WUTAI Mount Wutai, Considered the Most Sacred

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation in China Issue, Spring 2016

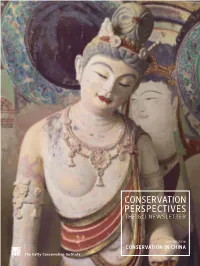

SPRING 2016 CONSERVATION IN CHINA A Note from the Director For over twenty-five years, it has been the Getty Conservation Institute’s great privilege to work with colleagues in China engaged in the conservation of cultural heritage. During this quarter century and more of professional engagement, China has undergone tremendous changes in its social, economic, and cultural life—changes that have included significant advance- ments in the conservation field. In this period of transformation, many Chinese cultural heritage institutions and organizations have striven to establish clear priorities and to engage in significant projects designed to further conservation and management of their nation’s extraordinary cultural resources. We at the GCI have admiration and respect for both the progress and the vision represented in these efforts and are grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage in China. The contents of this edition of Conservation Perspectives are a reflection of our activities in China and of the evolution of policies and methods in the work of Chinese conservation professionals and organizations. The feature article offers Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI a concise view of GCI involvement in several long-term conservation projects in China. Authored by Neville Agnew, Martha Demas, and Lorinda Wong— members of the Institute’s China team—the article describes Institute work at sites across the country, including the Imperial Mountain Resort at Chengde, the Yungang Grottoes, and, most extensively, the Mogao Grottoes. Integrated with much of this work has been our participation in the development of the China Principles, a set of national guide- lines for cultural heritage conservation and management that respect and reflect Chinese traditions and approaches to conservation. -

The Spreading of Christianity and the Introduction of Modern Architecture in Shannxi, China (1840-1949)

Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid Programa de doctorado en Concervación y Restauración del Patrimonio Architectónico The Spreading of Christianity and the introduction of Modern Architecture in Shannxi, China (1840-1949) Christian churches and traditional Chinese architecture Author: Shan HUANG (Architect) Director: Antonio LOPERA (Doctor, Arquitecto) 2014 Tribunal nombrado por el Magfco. y Excmo. Sr. Rector de la Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, el día de de 20 . Presidente: Vocal: Vocal: Vocal: Secretario: Suplente: Suplente: Realizado el acto de defensa y lectura de la Tesis el día de de 20 en la Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid. Calificación:………………………………. El PRESIDENTE LOS VOCALES EL SECRETARIO Index Index Abstract Resumen Introduction General Background........................................................................................... 1 A) Definition of the Concepts ................................................................ 3 B) Research Background........................................................................ 4 C) Significance and Objects of the Study .......................................... 6 D) Research Methodology ...................................................................... 8 CHAPTER 1 Introduction to Chinese traditional architecture 1.1 The concept of traditional Chinese architecture ......................... 13 1.2 Main characteristics of the traditional Chinese architecture .... 14 1.2.1 Wood was used as the main construction materials ........ 14 1.2.2 -

Knowing the Paths of Pilgrimage the Network of Pilgrimage Routes in Nineteenth-Century China

review of Religion and chinese society 3 (2016) 189-222 Knowing the Paths of Pilgrimage The Network of Pilgrimage Routes in Nineteenth-Century China Marcus Bingenheimer Temple University [email protected] Abstract In the early nineteenth century the monk Ruhai Xiancheng 如海顯承 traveled through China and wrote a route book recording China’s most famous pilgrimage routes. Knowing the Paths of Pilgrimage (Canxue zhijin 參學知津) describes, station by station, fifty-six pilgrimage routes, many converging on famous mountains and urban centers. It is the only known route book that was authored by a monk and, besides the descriptions of the routes themselves, Knowing the Paths contains information about why and how Buddhists went on pilgrimage in late imperial China. Knowing the Paths was published without maps, but by geo-referencing the main stations for each route we are now able to map an extensive network of monastic pilgrimage routes in the nineteenth century. Though most of the places mentioned are Buddhist sites, Knowing the Paths also guides travelers to the five marchmounts, popular Daoist sites such as Mount Wudang, Confucian places of worship such as Qufu, and other famous places. The routes in Knowing the Paths traverse not only the whole of the country’s geogra- phy, but also the whole spectrum of sacred places in China. Keywords Knowing the Paths of Pilgrimage – pilgrimage route book – Qing Buddhism – Ruhai Xiancheng – “Ten Essentials of Pilgrimage” 初探«參學知津»的19世紀行腳僧人路線網絡 摘要 十九世紀早期,如海顯承和尚在遊歷中國後寫了一本關於中國一些最著名 的朝聖之路的路線紀錄。這本「參學知津」(朝聖之路指引)一站一站地 -

Sustainable Tourism Development---How Sustainable Are China’S Cultural Heritage Sites

SUSTAINABLE TOURISM DEVELOPMENT---HOW SUSTAINABLE ARE CHINA’S CULTURAL HERITAGE SITES Dan Liao Tourism & Hospitality Department, Kent State University, OH, 44240 E-mail: [email protected] Dr. Philip Wang Kent State University Abstract In many countries around the world, the UNESCO World Heritage sites are major tourist attractions. The purpose of this study is to examine the level of sustainability of 28 cultural heritage sites in the People’s Republic of China. An analysis of the official websites of the –28 heritage sites was conducted using five sustainable development criteria: authenticity, tourists’ understanding of cultural value, commercial development, cooperation with the tourism industry and the quality of life in the community. Results showed most of the tourism destinations did well in authenticity preservation, commercial development and in obtaining economic revenue. For sustainable management of the sites, it was recommended that more attention should be paid to tourists’ understanding, tourism stakeholders’ collaboration and the environment of the community. As such, a triangular relationship is formed with management authorities, commercial enterprises and the community. 1.0 Introduction The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has considered World Heritage Sites in order to safeguard unique and outstanding properties for humankind in three categories: cultural, natural and mixed. Of the 911 sites around the world, 40 are located in People’s Republic of China, including 28 cultural, 8 natural and 4 mixed sites (Unesco.org). Cultural heritage tourism is defined as “visits by persons from outside the host community motivated wholly or in part by interest in historical, artistic, scientific or life style /heritage offerings of a community, region, group or institution” (Silberberg, 1995, p.361). -

Mount Wutai Visions of a Sacred Buddhist

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction Traveling around the Buddhist sacred range of Mount Wutai 五臺山 in northern detail of fi g. 0.6 China in 2005 (fi g. 0.1), I used as my guide a scaled-down photocopy of a map from a museum in Helsinki (see fi g. 4.1).1 Th e map, a hand-colored print from a woodblock panel carved in 1846 by a Mongol lama residing at Mount Wutai’s Cifu Temple 慈福寺 (Benevolent Virtues Temple), is a panorama of some 150 sites in a mountain range fi lled with pilgrims, festivities, fl ora and fauna, and cloud-borne deities, accompanied by parallel inscriptions in Mongolian, Chinese, and Tibetan. Th e map led me not only to monasteries, villages, and other landmarks but also into lively conversations with groups of Tibetan monks traveling or residing on the mountain. Without fail, the monks’ eyes lit up when they saw the map. Despite never having seen the image before, they expressed reverence, delight, and the resolve to scrutinize its every detail (fi g. 0.2). It was clear they recognized in the map a kindred vision of the mountain as an important place for Tibetan Buddhism. Although this vision had been physically erased from the mountain itself after more than a century, the map pictorialized and materialized what the monks had learned through a rich textual and oral tradition that had attracted them to Mount Wutai in the fi rst place. -

BTY9E 249 199 499 320 110 260 90 30 Start from 3/31/2017 – 11/30/2017

Discount Airfare available, Please call for details. Chinese and English Tour Guides Tour Code Adult Child (no bed) Child (w/bed) Single Supp. Add Room Designated Fee Tour Guide Tips Add. Transfer BTY9E 249 199 499 320 110 260 90 30 Start from 3/31/2017 – 11/30/2017. Arrive in Beijing every Friday. Blackout date: 6/30, July, 8/4, 8/11, 8/18, 9/22, and 9/29. The above tour fares are based on US Dollar. Child fares apply to children 2 – 12 years old. Child without extra bed has to share room with 2 adults. Child without extra bed does not include breakfast. Bilingual Guide Beijing <Optional Tours> --- $150USD/per person 1 Pingyao Ancient City’s Storage Battery Car Arrive at Beijing International Airport. Free Buddhist Temple in Mount Wutai transportation and transfer to the hotel. Due to Yanmenguan Great Wall Pass various flights, please wait for others patiently. Accommodation: Courtyard by Marriott Beijing or similar Shanxi Shadow play Yungang Grottos’ Storage Battery Car Beijing Experience Shanxi Exclusive Handicrafts 2 (B/L/D) Mountain Wutai Vegetarian Cuisine After breakfast, visit The Summer Palace in Qing dynasty, the biggest royal garden in China. At noon, taste the authentic hotpot, Beijing Dong After breakfast, proceed to Hunyuan County in Shanxi for visiting Hanging Lai Shun lamb. After lunch, consult specialists about health for free in Royal Physician Hall. In the afternoon, continue to the world largest plaza, Temple, which is a temple built in the cliff. (Designated Tour) Built more Tiananmen Square and the National Theatre. Then, proceed to see great than 1,500 years ago, this temple is notable not only for its location on a sheer cultural heritage- the National Palace. -

China Danxia

ASIA / PACIFIC CHINA DANXIA CHINA WORLD HERITAGE NOMINATION - IUCN TECHNICAL EVALUATION CHINA DANXIA (CHINA) - ID Nº 1335 1. DOCUMENTATION i) Date nomination received by IUCN: 15th March 2009 ii) Additional information requested: IUCN requested supplementary information after the mission regarding a range of issues related to the scientifi c framework for China Danxia, site selection, comparative analysis, integrity, protection and management of the property and the protection of wider catchments. A response to all questions raised was provided by the State Party. iii) UNEP-WCMC data sheet: Sourced from original nomination. iv) Additional literature consulted: Engels, B., Ohnesorge and Burmester, A. (eds) (2009) Nominations and Management of Serial Natural World Heritage Properties, Present situation, Challenges and Opportunities. Federal Agency for Nature Conservation, Bonn; Guizhou Institute of Architectural Design (2008) Chishui of China Danxia Management Plan. Guizhou Tongh Co Ltd on Planning and Consultation, Chishui; Grimes, K., Wray, R., Spate, A. and Household, I. (2009) Karst and Pseudokarst in Northern Australia. draft report to the Commonwealth of Australia Department of Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts; Optimal Karst Management. Hall; Lockwood, M., Worboys, G.L. and Kothari, A. (2006); Protected Area Management, A Global Guide. IUCN and Earthscan, London; Longhushan-Guifeng National Park Heritage Coordination Committee (2008) Protection and Management Plan for Longhushan World Natural Heritage Nominated Site 2008-2012. Longhushan-Guifeng National Park Yingtan City and Shangrao City Jiangxi Province; OCWHN [Offi ce of China World Heritage Nomination] (2009) Joint Management Plan of China Danxia. Offi ce of China Danxia World Heritage Nomination, Changsha City, China; Ro, L. and Chen, H. -

Foguangsi on Mount Wutai: Architecture of Politics and Religion Sijie Ren University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 1-1-2016 Foguangsi on Mount Wutai: Architecture of Politics and Religion Sijie Ren University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Studies Commons, History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Ren, Sijie, "Foguangsi on Mount Wutai: Architecture of Politics and Religion" (2016). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1967. http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1967 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1967 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Foguangsi on Mount Wutai: Architecture of Politics and Religion Abstract Foguangsi (Monastery of Buddha’s Radiance) is a monastic complex that stands on a high terrace on a mountainside, in the southern ranges of Mount Wutai, located in present-day Shanxi province. The mountain range of Wutai has long been regarded as the sacred abode of the Bodhisattva Mañjuśrī and a prominent center of the Avataṃsaka School. Among the monasteries that have dotted its landscape, Foguangsi is arguably one of the best-known sites that were frequented by pilgrims. The er discovery of Foguangsi by modern scholars in the early 20th century has been considered a “crowning moment in the modern search for China’s ancient architecture”. Most notably, the Buddha Hall, which was erected in the Tang dynasty (618-907 CE), was seen as the ideal of a “vigorous style” of its time, and an embodiment of an architectural achievement at the peak of Chinese civilization. -

Digitisation of Scenic and Historic Interest Areas in China

ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume II-5/W3, 2015 25th International CIPA Symposium 2015, 31 August – 04 September 2015, Taipei, Taiwan Digitisation of Scenic and Historic Interest Areas in China Chen Yang a, *, Gillian Lawson b, Jeannie Simc, a World Heritage Institute of Training and Research for the Asia and the Pacific Region under the auspices of UNESCO (WHITRAP) – [email protected] b Dept. of Landscape Architecture, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia – [email protected] c Dept. of Landscape Architecture, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia – [email protected] Topic E, E-2 KEY WORDS: Digital Scenic Area project, Scenic Area, representation, Slender West Lake, China ABSTRACT: Digital documents have become the major information source for heritage conservation practice. More heritage managers today use electronic maps and digital information systems to facilitate management and conservation of cultural heritage. However, the social aspects of digital heritage have not been sufficiently recognised. The aim of this paper is to examine China’s ‘Digital Scenic Area’ project, a national program started in 2004, to reveal the political and economic powers behind digital heritage practice. It was found that this project was only conducted within the most popular tourist destinations in China. Tourism information was the main object but information about landscape cultures were neglected in this project. This project also demonstrated that digital management was more like a political or economic symbol rather than a tool for heritage conservation. However, using digital technologies are still considered by the local government as a highly objective way of heritage management. -

Taming the Sacred? Pilgrimage, Worship and Tourism in Contemporary China

Historisch Tijdschrift Groniek, 215 - Devotie Robert Shepherd Taming the sacred? Pilgrimage, Worship and Tourism in Contemporary China In this paper I describe and analyze the impact of tourism on the Buddhist pilgrimage destination of Mount Wutai (Ch. Wutai Shan) in Shanxi, China. Designated a national park in 1982 and world heritage site in 2009, Wutai Shan now attracts more than four million visitors a year, raising concerns about degradation of a sacred landscape. But, contrary to state suggestions, religious practice remains widespread among visitors, although the extent to which most visitors identify as Buddhists is questionable. In this paper I describe and analyze the impact of tourism on the Buddhist pilgrimage destination of Mount Wutai (Ch. Wutai Shan) in Shanxi, China. Wutai Shan has been one of the most important Buddhist sites in East Asia for centuries, drawing visitors from China, Tibet, Mongolia, Nepal, India, and Japan. In 1982 the Wutai Valley was included on China’s first list of national parks and in 2009 (was) listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site. In the last two decades Wutai Shan has become one of the most visited religious destinations in northern China, attracting approximately four million annual visitors, the vast majority of whom are citizens of the People’s Republic of China. Is this then yet another example of a once-sacred place that has been “Disneyfied” by mass tourism? In other words, does Wutai Shan demonstrate the corroding effects tourism is supposed to have on the sacred and authentic? At least in this case, the answer is no. -

Danxia (China) No 1335

2. THE PROPERTY Danxia (China) Extensive cultural values of China Danxia are described No 1335 at length in the nomination dossier. With millennia of human occupation, the region and the individual sites within it are filled with rich cultural associations, ranging from prehistoric human use of natural resources and ancient agricultural settlement to contemporary human 1. BASIC DATA activities with long histories including farming, religious and scholarly activities, tourism and scientific activities. Official name as proposed by the State Party: Each of the six areas has notable cultural associations and resources, including strong associations with and China Danxia material evidences of Taoist, Buddhist and Confucian cultures. Location: China already has inscribed a number of World Heritage Chishui, Zunyi City, Guizhou Province Sites related to significant representations of these Taining, Sanming City, Fujian Province cultures that are justified under criterion (vi). They Langshan, Shaoyang City, Hu’nan Province include Lushan National Park (1996), where Mount Danxiashan, Shaoguan City, Guangdong Province Lushan is described as “one of the spiritual centres of Longhushan, Yingtan City, Shangrao City, Chinese civilization. Buddhist and Taoist temples, along Jiangxi Province with landmarks of Confucianism…”; Mount Qingcheng Jianglangshan, Quzhou City, Zhejiang Province and the Dujiangyan Irrigation System (2000), with People’s Republic of China temples closely associated with the founding of Taoism; Mogao Caves (1987), “spanning 1,000 years of Buddhist Brief description: art”; Mount Emei Scenic Area, including Leshan Giant Buddha Scenic Area (1996); Mount Wutai (2009), “one This nomination proposes the inscription of six areas, of the four sacred Buddhist mountains in China”; and with buffer zones, that are representative of Danxia (red Mount Taishan (1987), associated with the emergence bed) landscapes in the southern humid zones of China. -

THE CASE of the ITINERANT MONK- ARCHITECT MIAOFENG FUDENG (1540-1613) Caroline Bodolec

TECHNOLOGY AND PATRONAGE OF CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS IN LATE MING CHINA: THE CASE OF THE ITINERANT MONK- ARCHITECT MIAOFENG FUDENG (1540-1613) Caroline Bodolec To cite this version: Caroline Bodolec. TECHNOLOGY AND PATRONAGE OF CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS IN LATE MING CHINA: THE CASE OF THE ITINERANT MONK- ARCHITECT MIAOFENG FU- DENG (1540-1613). Ming Qing Studies 2018, 2018, 978-88-85629-38-7. halshs-02428821 HAL Id: halshs-02428821 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02428821 Submitted on 6 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. TECHNOLOGY AND PATRONAGE OF CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS IN LATE MING CHINA - THE CASE OF THE ITINERANT MONK-ARCHITECT MIAOFENG FUDENG (1540-1613)1 CAROLINE BODOLEC (Centre d'études sur la Chine moderne et contemporaine, UMR 8173 Chine, Corée, Japon. CNRS, France) This paper focuses on the figure of Miaofeng Fudeng 妙峰福登 (1540-1613), a Chan Buddhist monk. After a first period devoted to religious and spiritual activ- ities (pilgrimages, pious actions, hermitage and so on), his life changed at the age of 42, when he received funds for building a Buddhist temple and a pagoda from several members of imperial family, notably the Empress Dowager Li Shi 李 氏 (Cisheng Huang taihou) 慈 聖 皇 太 后 , mother of The Wanli Emperor (1572-1620).