Mount Wutai Visions of a Sacred Buddhist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation in China Issue, Spring 2016

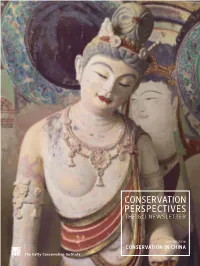

SPRING 2016 CONSERVATION IN CHINA A Note from the Director For over twenty-five years, it has been the Getty Conservation Institute’s great privilege to work with colleagues in China engaged in the conservation of cultural heritage. During this quarter century and more of professional engagement, China has undergone tremendous changes in its social, economic, and cultural life—changes that have included significant advance- ments in the conservation field. In this period of transformation, many Chinese cultural heritage institutions and organizations have striven to establish clear priorities and to engage in significant projects designed to further conservation and management of their nation’s extraordinary cultural resources. We at the GCI have admiration and respect for both the progress and the vision represented in these efforts and are grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage in China. The contents of this edition of Conservation Perspectives are a reflection of our activities in China and of the evolution of policies and methods in the work of Chinese conservation professionals and organizations. The feature article offers Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI a concise view of GCI involvement in several long-term conservation projects in China. Authored by Neville Agnew, Martha Demas, and Lorinda Wong— members of the Institute’s China team—the article describes Institute work at sites across the country, including the Imperial Mountain Resort at Chengde, the Yungang Grottoes, and, most extensively, the Mogao Grottoes. Integrated with much of this work has been our participation in the development of the China Principles, a set of national guide- lines for cultural heritage conservation and management that respect and reflect Chinese traditions and approaches to conservation. -

US Pagans and Indigenous Americans: Land and Identity

religions Article US Pagans and Indigenous Americans: Land and Identity Lisa A. McLoughlin Independent Scholar, Northfield, MA 01360, USA; [email protected] Received: 2 January 2019; Accepted: 27 February 2019; Published: 1 March 2019 Abstract: In contrast to many European Pagan communities, ancestors and traditional cultural knowledge of Pagans in the United States of America (US Pagans) are rooted in places we no longer reside. Written from a US Pagan perspective, for an audience of Indigenous Americans, Pagans, and secondarily scholars of religion, this paper frames US Paganisms as bipartite with traditional and experiential knowledge; explores how being transplanted from ancestral homelands affects US Pagans’ relationship to the land we are on, to the Indigenous people of that land, and any contribution these may make to the larger discussion of indigeneity; and works to dispel common myths about US Pagans by offering examples of practices that the author suggests may be respectful to Indigenous American communities, while inviting Indigenous American comments on this assessment. Keywords: US Pagans; Indigenous Americans; identity; land; cultural appropriation; indigeneity 1. Introduction Indigenous American scholar Vine Deloria Jr. (Deloria 2003, pp. 292–93) contends: “That a fundamental element of religion is an intimate relationship with the land on which the religion is practiced should be a major premise of future theological concern.” Reading of Indigenous American and Pagan literatures1 indicates that both communities, beyond simply valuing their relationship with the land, consider it as part of their own identity. As for example, in this 1912 Indigenous American quote: “The soil you see is not ordinary soil—it is the dust of the blood, the flesh, and the bones of our ancestors. -

3 Days Datong Pingyao Classical Tour

[email protected] +86-28-85593923 3 days Datong Pingyao classical tour https://windhorsetour.com/datong-pingyao-tour/datong-pingyao-classical-tour Datong Pingyao Exploring the highlights of Datong and Pingyao's World Culture Heritage sites gives you a chance to admire the superb artistic attainments of the craftsmen and understand the profound Chinese culture in-depth. Type Private Duration 3 days Theme Culture and Heritage, Family focused, Winter getaways Trip code DP-01 Price From € 304 per person Itinerary This is a 3 days’ culture discovery tour offering the possibility to have a glimpse of the profound culture of Datong and Pingyao and the outstanding artistic attainments of the craftsmen of ancient China in a short time. The World Cultural Heritage Site - Yungang Grottoes, Shanhua Monastery, Hanging Monastery, as well as Yingxian Wooden Pagoda gives you a chance to admire the rich Buddhist culture of ancient China deeply. The Pingyao Ancient City, one of the 4 ancient cities of China and a World Cultural Heritage site, displays a complete picture of the prosperity of culture, economy, and society of the Ming and Qing Dynasties for tourists. Day 01 : Datong arrival - Datong city tour Arrive Datong in the early morning, your experienced private guide, and a comfortable private car with an experienced driver will be ready (non-smoking) to serve for your 3 days ancient China discovery starts. The highlights today include Shanhua Monastery, Nine Dragons Wall, as well as Yungang Grottoes. Shanhua Monastery is the largest and most complete existing monastery in China. The Nine Dragons Wall in Datong is the largest Nine Dragons Wall in China, which embodies the superb carving skills of ancient China. -

The Spreading of Christianity and the Introduction of Modern Architecture in Shannxi, China (1840-1949)

Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid Programa de doctorado en Concervación y Restauración del Patrimonio Architectónico The Spreading of Christianity and the introduction of Modern Architecture in Shannxi, China (1840-1949) Christian churches and traditional Chinese architecture Author: Shan HUANG (Architect) Director: Antonio LOPERA (Doctor, Arquitecto) 2014 Tribunal nombrado por el Magfco. y Excmo. Sr. Rector de la Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, el día de de 20 . Presidente: Vocal: Vocal: Vocal: Secretario: Suplente: Suplente: Realizado el acto de defensa y lectura de la Tesis el día de de 20 en la Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid. Calificación:………………………………. El PRESIDENTE LOS VOCALES EL SECRETARIO Index Index Abstract Resumen Introduction General Background........................................................................................... 1 A) Definition of the Concepts ................................................................ 3 B) Research Background........................................................................ 4 C) Significance and Objects of the Study .......................................... 6 D) Research Methodology ...................................................................... 8 CHAPTER 1 Introduction to Chinese traditional architecture 1.1 The concept of traditional Chinese architecture ......................... 13 1.2 Main characteristics of the traditional Chinese architecture .... 14 1.2.1 Wood was used as the main construction materials ........ 14 1.2.2 -

The Daoist Tradition Also Available from Bloomsbury

The Daoist Tradition Also available from Bloomsbury Chinese Religion, Xinzhong Yao and Yanxia Zhao Confucius: A Guide for the Perplexed, Yong Huang The Daoist Tradition An Introduction LOUIS KOMJATHY Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 175 Fifth Avenue London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10010 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com First published 2013 © Louis Komjathy, 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Louis Komjathy has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury Academic or the author. Permissions Cover: Kate Townsend Ch. 10: Chart 10: Livia Kohn Ch. 11: Chart 11: Harold Roth Ch. 13: Fig. 20: Michael Saso Ch. 15: Fig. 22: Wu’s Healing Art Ch. 16: Fig. 25: British Taoist Association British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: 9781472508942 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Komjathy, Louis, 1971- The Daoist tradition : an introduction / Louis Komjathy. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4411-1669-7 (hardback) -- ISBN 978-1-4411-6873-3 (pbk.) -- ISBN 978-1-4411-9645-3 (epub) 1. -

Download Mountains.Pdf

MOUNTAINS AND THE SACRED Mountains loom large in any landscape and have long been invested with sacredness by many peoples around the world. They carry a rich symbolism. The vertical axis of the mountain drawn from its peak down to its base links it with the world-axis, and, as in the case of the Cosmic Tree (cf. Trees and the Sacred), is identified as the centre of the world. This belief is attached, for example, to Mount Tabor of the Israelites and Mount Meru of the Hindus. Besides natural mountains being invested with the sacred, there are numerous examples of mountains being built, such as the Mesopotamia ziggurats, the pyramids in Egypt [cf. Giza Plateau, Egypt], the pre- Columbian teocallis, and the temple-mountain of Borobudur. In most cases, the tops of real and artificial mountains are the locations for sanctuaries, shrines, or altars. In Ancient Greece the pre-eminent god of the mountain was Zeus for whom there existed nearly one hundred mountain cults. Zeus, who was born and brought up on a mountain (he was allegedly born in a cave [cf. The Sacred Cave] on Mount Ida on Crete), and who ruled supreme on Mount Olympus, was a god of rain and lightning (to Zeus as a god of rain is dedicated the sanctuary of Zeus Ombrios on Hymettos). Mountains figure a great deal in Greek mythology -- the Muses occupy on Mount Helikon, Apollo is associated with Parnassos [cf. Delphi], and Athena with the Athenian Acropolis. In Japan, Mount Fuji (Fujiyama) is revered by Shintoists as sacred to the goddess Sengen-Sama, whose shrine is found at the summit. -

Sacred Mountains

SACRED MOUNTAINS How the revival of Daoism is turning China's ecological crisis around Sacred Mountains Allerd Stikker First published in 2014 by Bene Factum Publishing Ltd PO Box 58122 London SW8 5WZ Email: [email protected] www.bene-factum.co.uk SACRED ISBN: 978-1-909657-56-4 Text © Allerd Stikker Illustrations © Rosa Vitalie MOUNTAINS How the revival of Daoism is The rights of Allerd Stikker to be identified as the Author of this Work have been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, turning China's ecological Designs and Patents Act, 1988. crisis around The rights of Rosa Vitalie to be identified as the Illustrator of this Work have been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. All rights reserved. This book is sold under the condition that no part of it may be reproduced, copied, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior permission in writing of the publisher. A CIP catalogue record of this is available from the British Library. Cover and book design by Rosa Vitalie Editor Maja Nijessen Printed and bound in Slovenia on behalf of Latitude Press Picture credits: All photographs are from the ARC archives or the Design and illustrations Rosa Vitalie personal collections of the Stikker family, Michael Shackleton and Lani van Petten. Bene Factum Publishing Contents Foreword by Martin Palmer vii Introduction by Allerd Stikker ix 1. A Journey into Daoism 3 A Personal Story 2. The Price of a Miracle 33 The Ecology Issue on Taiwan 3. -

Knowing the Paths of Pilgrimage the Network of Pilgrimage Routes in Nineteenth-Century China

review of Religion and chinese society 3 (2016) 189-222 Knowing the Paths of Pilgrimage The Network of Pilgrimage Routes in Nineteenth-Century China Marcus Bingenheimer Temple University [email protected] Abstract In the early nineteenth century the monk Ruhai Xiancheng 如海顯承 traveled through China and wrote a route book recording China’s most famous pilgrimage routes. Knowing the Paths of Pilgrimage (Canxue zhijin 參學知津) describes, station by station, fifty-six pilgrimage routes, many converging on famous mountains and urban centers. It is the only known route book that was authored by a monk and, besides the descriptions of the routes themselves, Knowing the Paths contains information about why and how Buddhists went on pilgrimage in late imperial China. Knowing the Paths was published without maps, but by geo-referencing the main stations for each route we are now able to map an extensive network of monastic pilgrimage routes in the nineteenth century. Though most of the places mentioned are Buddhist sites, Knowing the Paths also guides travelers to the five marchmounts, popular Daoist sites such as Mount Wudang, Confucian places of worship such as Qufu, and other famous places. The routes in Knowing the Paths traverse not only the whole of the country’s geogra- phy, but also the whole spectrum of sacred places in China. Keywords Knowing the Paths of Pilgrimage – pilgrimage route book – Qing Buddhism – Ruhai Xiancheng – “Ten Essentials of Pilgrimage” 初探«參學知津»的19世紀行腳僧人路線網絡 摘要 十九世紀早期,如海顯承和尚在遊歷中國後寫了一本關於中國一些最著名 的朝聖之路的路線紀錄。這本「參學知津」(朝聖之路指引)一站一站地 -

Origin Narratives: Reading and Reverence in Late-Ming China

Origin Narratives: Reading and Reverence in Late-Ming China Noga Ganany Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Noga Ganany All rights reserved ABSTRACT Origin Narratives: Reading and Reverence in Late Ming China Noga Ganany In this dissertation, I examine a genre of commercially-published, illustrated hagiographical books. Recounting the life stories of some of China’s most beloved cultural icons, from Confucius to Guanyin, I term these hagiographical books “origin narratives” (chushen zhuan 出身傳). Weaving a plethora of legends and ritual traditions into the new “vernacular” xiaoshuo format, origin narratives offered comprehensive portrayals of gods, sages, and immortals in narrative form, and were marketed to a general, lay readership. Their narratives were often accompanied by additional materials (or “paratexts”), such as worship manuals, advertisements for temples, and messages from the gods themselves, that reveal the intimate connection of these books to contemporaneous cultic reverence of their protagonists. The content and composition of origin narratives reflect the extensive range of possibilities of late-Ming xiaoshuo narrative writing, challenging our understanding of reading. I argue that origin narratives functioned as entertaining and informative encyclopedic sourcebooks that consolidated all knowledge about their protagonists, from their hagiographies to their ritual traditions. Origin narratives also alert us to the hagiographical substrate in late-imperial literature and religious practice, wherein widely-revered figures played multiple roles in the culture. The reverence of these cultural icons was constructed through the relationship between what I call the Three Ps: their personas (and life stories), the practices surrounding their lore, and the places associated with them (or “sacred geographies”). -

The Image of China As a Tourist Destination and Its Market in Spain

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repositorio Universidad de Zaragoza FACULTAD DE EMPRESA Y GESTIÓN PÚBLICA Máster en Dirección y Planificación de Turismo The Image of China as a Tourist Destination and its Market in Spain Hao Zhang Huesca, January, 18th, 2013 The Image of China as a Destination and Its Market in Spain Content I Abstract...........................................................................................5 1. INTRODUCTION..........................................................................6 1.1. OBJECTIVES...............................................................................................7 1.2. STRUCTURE...............................................................................................8 1.3. METHODOLOGY........................................................................................9 2. LITERATURE REVIEW..............................................................10 2.1. TOURIST DESTINATION IMAGE.........................................................10 2.2. COGNITIVE IMAGE DIMENSIONS......................................................13 2.2.1. Dimensionality........................................................................................13 2.2.2. The Image of China as Tourist Destination……………………..…...17 2.2.2.1. General Introduction of China…………...…………………………..17 2.2.2.2. Natural Resources……...………………………………………………18 2.2.2.3. Infrastructures…………...……………………………………………20 2.2.2.4. Tourist leisure and recreation…………….…………..………………22 -

Download Article (PDF)

4th International Education, Economics, Social Science, Arts, Sports and Management Engineering Conference (IEESASM 2016) Several Suggestions on Development of Tourism Economy in China Ying Dai School of Travel Information, Changjiang Professional College, Wuhan Hubei, 430074, China Key words: Chinese tourism, Tourism economy, Tourism pattern. Abstract. With the constant improvement of national economy, more and more developing countries gradually start to pay attention to the development of their tourism economy. As different countries or regions have different economic situation and custom, the development of tourism in various countries shows different status. This paper mainly discusses problems existing in the development of Chinese tourism and relevant policies for solving such problems and provides reference for the future development of Chinese tourism. Introduction Since the implementation of reform and opening-up policy in China, the living quality of people has improved greatly. Their economic incomes start to increase gradually and their lifestyle and consumption attitude also changes constantly. While material life and civilization of people are constantly improved, they have higher requirements for spiritual civilization. Traveling in holidays and festivals has become a fashion of tourism, which makes tourism economy emerge. Now, tourism economy has become an indispensable economic source in national income. However, we should be aware of some problems and restraining factors of the development of tourism economy in China. We should endeavor to solve such problems and make due contributions to better development of tourism economy. Development status of tourism economy in China Due to vast territory, geology, famous mountains, great waters and tourist attractions of China, Chinese tourism has good advantages compared to other countries, including the following: 1. -

Buddhism, Four Sacred Sites of Sì Dà Fójiào Míng Shān 四大佛教名山

◀ Buddhism, Chan Comprehensive index starts in volume 5, page 2667. Buddhism, Four Sacred Sites of Sì Dà Fójiào Míng Shān 四大佛教名山 The four sacred sites of Buddhism in China long journeys, from their points of departure to one of are Wutai Shan, Emei Shan, Jiuhua Shan, and the mountains, by making a prostration— touching the Putuoshan, mountain homes of Buddhist en- ground with the head every three steps. It was customary lightened ones. Although the religious com- for pilgrims to visit in this way all the temples and shrines in the mountains. Lay Buddhists visited these mountains plexes at these sites are smaller than those in great numbers to make vows (huanyuan) or to perform existing at the height of Buddhism’s existence penance. Many nonbelievers also traveled to the sacred China, the “holy mountains” remain attrac- sites to accomplish a feat from which they could derive tions for their religious context and artifacts prestige. The pilgrimages were often in groups because and for their natural beauty. the journey to the nearest cities to the sites was sometimes long and dangerous. he “four most famous Buddhist mountains” (sida Wutai Shan: Five Fojiao mingshan) were traditionally considered as Terraces Mountain bodhimanda (mountain residences) of bodhisat- tvas (pusa in Chinese), spiritual beings who, according to Wutai Shan, or the “five terraces mountain,” in Shanxi Buddhist scriptures, assist all sentient beings in transcend- Province, is the bodhimanda for Wenshu Pusa (the bo- ing suffering. The Chinese tradition of “paying respect to dhisattva of Wisdom; in Sanskrit, Manjusri, “Gentle a holy mountain” through pilgrimage (chaobai sheng shan) Glory”).