The New Geo-Economics of a “Rising” India: State Transformation and the Recasting of Foreign Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9 Post & Telecommunications

POST AND TELECOMMUNICATIONS 441 9 Post & Telecommunications ORGANISATION The Office of the Director General of Audit, Post and Telecommunications has a chequered history and can trace its origin to 1837 when it was known as the Office of the Accountant General, Posts and Telegraphs and continued with this designation till 1978. With the departmentalisation of accounts with effect from April 1976 the designation of AGP&T was changed to Director of Audit, P&T in 1979. From July 1990 onwards it was designated as Director General of Audit, Post and Telecommunications (DGAP&T). The Central Office which is the Headquarters of DGAP&T was located in Shimla till early 1970 and thereafter it shifted to Delhi. The Director General of Audit is assisted by two Group Officers in Central Office—one in charge of Administration and other in charge of the Report Group. However, there was a difficult period from November 1993 till end of 1996 when there was only one Deputy Director for the Central office. The P&T Audit Organisation has 16 branch Audit Offices across the country; while 10 of these (located at Chennai, Delhi, Hyderabad, Kapurthala, Lucknow, Mumbai, Nagpur, Patna and Thiruvananthapuram as well as the Stores, Workshop and Telegraph Check Office, Kolkata) were headed by IA&AS Officers of the rank of Director/ Dy. Director. The charges of the remaining branch Audit Offices (located at Ahmedabad, Bangalore, Bhopal, Cuttack, Jaipur and Kolkata) were held by Directors/ Dy. Directors of one of the other branch Audit Offices (as of March 2006) as additional charge. P&T Audit organisation deals with all the three principal streams of audit viz. -

Public Notice-Merged.Pdf

No. 30-02/202 0-ws Government of lndia Ministry of Communications Department of Posts (PO Division) Dak Bhawan, Sansad Marg New Delhi- 110 001 Dated: 8th September, 2020 PUBLIC NOTICE SUBJECT: SEEKtNG suGGEsrloNs/FEEDBAcK/coMMENTS/|NpursrurEWs FROM GENERAL PUBLIC/STAKEHOLDERS ON THE DRAFT "INDIAN POST OFFICE RULES,2020" The central Government proposes to make a new set of lndian post office Rules' 2020 (lPo Rules, 2020) which wiil be in supersession of lpo Rures, 1933. passage 2- with the of time and induction of technorogy, the working of the post office has changed significanfly since 1933, so there is a need for a new set of rules in sync with the today's environment. 3. ln the new set of rpo Rures, 2020. some new rures have been framed, obsolete rules have been dereted from and many rures have been re- framed/modified in sync with the present scenario. The lndian post office Rules, 2020 will be a new set of Rures which wiil govern the functioning of the post offices henceforth. 4. ln the context of the above, the draft of proposed rpo Rures,2020 is hereby notified for information, seeking suggestions/feedbacucomments/inputs/views from general public/stakehorders/customers. Notice is hereby given that the suggestions/feedbacucomments/inputs/views received with regard to the said draft lPo Rules, 2020 will be taken into consideration tilr 6:00 p.m. of 9th october, 2020. 5. Suggestions/Feedback/comments/rnputsA/iews, if any, may be addressed to Ms. Sukriti Gupta, Assistant Director General (postal Operations, Room No. 340, Third Floor, Dak Bhawan, sansad Marg, New Derhi-i10001 , Ter. -

POSTAL SAVINGS Reaching Everyone in Asia

POSTAL SAVINGS Reaching Everyone in Asia Edited by Naoyuki Yoshino, José Ansón, and Matthias Helble ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK INSTITUTE Postal Savings - Reaching Everyone in Asia Edited by Naoyuki Yoshino, José Ansón, and Matthias Helble ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK INSTITUTE © 2018 Asian Development Bank Institute All rights reserved. First printed in 2018. ISBN: 978 4 89974 083 4 (Print) ISBN: 978 4 89974 084 1 (PDF) The views in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI), its Advisory Council, ADB’s Board or Governors, or the governments of ADB members. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. ADBI uses proper ADB member names and abbreviations throughout and any variation or inaccuracy, including in citations and references, should be read as referring to the correct name. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “recognize,” “country,” or other geographical names in this publication, ADBI does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Users are restricted from reselling, redistributing, or creating derivative works without the express, written consent of ADBI. ADB recognizes “China” as the People’s Republic of China. Note: In this publication, “$” refers to US dollars. Asian Development Bank Institute Kasumigaseki Building 8F 3-2-5, Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda-ku Tokyo 100-6008, Japan www.adbi.org Contents List of illustrations v List of contributors ix List of abbreviations xi Introduction 1 Naoyuki Yoshino, José Ansón, and Matthias Helble PART I: Global Overview 1. -

Is India Fit for a Role in Global Governance? the Predicament of Fragile Domestic Structures and Institutions

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Wulf, Herbert Working Paper Is India Fit for a Role in Global Governance? The Predicament of Fragile Domestic Structures and Institutions Global Cooperation Research Papers, No. 4 Provided in Cooperation with: University of Duisburg-Essen, Käte Hamburger Kolleg / Centre for Global Cooperation Research (KHK/GCR21) Suggested Citation: Wulf, Herbert (2014) : Is India Fit for a Role in Global Governance? The Predicament of Fragile Domestic Structures and Institutions, Global Cooperation Research Papers, No. 4, University of Duisburg-Essen, Käte Hamburger Kolleg / Centre for Global Cooperation Research (KHK/GCR21), Duisburg, http://dx.doi.org/10.14282/2198-0411-GCRP-4 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/214697 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Advancing Financial Inclusion Through Access to Insurance: the Role Of

Advancing financial inclusion through access to insurance: the role of postal networks Published by the Universal Postal Union (UPU) Berne, Switzerland and by the International Labour Organization (ILO) Geneva, Switzerland. Printed in Switzerland by the printing services of the International Bureau of the UPU. Copyright © 2016 UPU / ILO All rights reserved Except as otherwise indicated, the copyright in this publication is owned by the UPU and the ILO. Reproduction is authorized for non-commercial purposes, subject to proper acknowledgement of the source. This authorization does not extend to any material identified in this publication as being the copyright of a third party. Authorization to reproduce such third party materials must be obtained from the copyright holders concerned. AUTHOR: Guilherme Suedekum TITLE: Advancing financial inclusion through access to insurance: the role of postal networks ISBN: 978-92-95025-84-4 DESIGN: UPU Graphic Unit CONTACT: Nils Clotteau, UPU, [email protected] Craig Churchill, ILO, [email protected] COVER PICTURE: © 2009 Indian Post This study is the result of a joint effort between the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the Universal Postal Union (UPU). It was prepared by Guilherme Suedekum, financial inclusion independent consultant, with the guidance and advice of Craig Churchill, team leader of the ILO’s Impact Insurance Facility, and Nils Clotteau, Acknowledgements Partnerships and Resource Mobilization Expert at the UPU. The team is especially grateful to Dauren Turysbekov, Director of the Department of External Affairs at Kazpost, Michel Kabré, Director of Financial Services at SONAPOST, Titus Juma, Director of Payment Services at the Postal Corporation of Kenya, M’hamed El-Moussaoui, Assistant Director General of Al Barid Bank, and Rajagopal Krishnaswamy, Managing Director at Professional Life Assurance. -

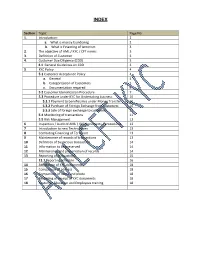

2 A. What Is Money Laundering 2 B. What Is Financing of Terrorism 3 2

INDEX Section Topic Page No 1. Introduction: 2 a. What is money laundering 2 b. What is Financing of terrorism 3 2. The objective of AML / KYC / CFT norms 3 3. Definition of Customer 3 4. Customer Due Diligence (CDD) 3 4.1 General Guidelines on CDD 3 5 KYC Policy 4 5.1 Customer Acceptance Policy 4 a. General 4 b. Categorization of Customers 5 c. Documentation required 6 5.2 Customer Identification Procedure 7 5.3 Procedure under KYC for Undertaking business 10 5.3.1 Payment to beneficiaries under Money Transfer 10 5.3.2 Purchase of Foreign Exchange from customers 10 5.3.3 Sale of foreign exchange to customers 11 5.4 Monitoring of transactions 11 5.5 Risk Management 12 6 Inspection / Audit of AML \ KYC documents / procedures 13 7 Introduction to new Technologies 13 8 Combating Financing of Terrorism 13 9 Maintenance of records of transactions 13 10 Definition of Suspicious transaction 14 11 Information to be preserved 14 12 Maintenance and preservation of records 14 13 Reporting of transactions 15 13.1 Reporting schedule 16 14 Attestation of KYC documents 18 15 Comparison of address 18 16 Comparison of name and photo 18 17 Recording of receipt of KYC documents 18 18 Customer Education and Employees training 18 Guidelines on Know Your Customer (KYC) Norms / Anti-Money Laundering (AML) Standards / Combating Financing of Terrorism (CFT) Norms under Prevention of Money Laundering Act, PMLA, 2002 as amended by Prevention of Money Laundering (Amendment) Act, 2009 for International Money Transfer Services(Inward) under the Money Transfer Service Scheme (MTSS) and Money Changing Services in India Post 1. -

Roaring Tiger Or Lumbering Elephant?

aUGUST 2006 ANALYSIS MARK THIRLWELL Roaring tiger or Program Director International Economy lumbering elephant? Tel. +61 2 8238 9060 [email protected] Assessing the performance, prospects and problems of India’s development model.1 In the past, there has been plenty of scepticism about India’s economic prospects: for many, Charles De Gaulle’s aphorism regarding Brazil, that it was a country with enormous potential, and always would be, seemed to apply equally well to the South Asian economy. While the ‘tiger’ economies of East Asia were enjoying economic take-off on the back of investment- and export-led growth, the lumbering Indian elephant seemed set to be a perpetual also-ran in the growth stakes. Yet following a series of reform efforts, first tentatively in the 1980s, and then with much more conviction in the 1990s, the Indian economic model has been transformed, and so too India’s growth prospects. High profile successes in the new economy sectors of information technology (IT) and business process outsourcing (BPO), along with faster economic growth, triggered a widespread rethink regarding India’s economic prospects, and a wave of foreign portfolio investment flowed into Indian markets. Perhaps India was set to be a tiger after all. Yet this new-found optimism received a setback in May and June of this year, when there were sharp falls in Indian stock markets. Had the optimism been overdone, and was another re-rating of India’s economic prospects on the cards? Perhaps India was only a lumbering elephant after all? This paper takes a closer look at the new Indian development model. -

Economic Performance the Indian Economy Achieved a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Growth Rate of 8.1% in FY2005 (1 April 2005–31 March 2006)

India The Indian economy grew by 8.1% in FY2005, according to official estimates. Price pressure has been building as the authorities are unlikely to have the resources to cushion domestic fuel prices from the full extent of fuel import price increases for much longer. On the supply side, growth will continue to be fueled by the opening up of space for private investment. India faces two key policy challenges as the economy undergoes a structural transformation. First, it must continue consolidating its fiscal position. It will have to do so while ensuring both adequate hard infrastructure improvements to support industrial and high-skill services development, and public investment to advance rural productivity and human development. Second, it needs to improve the investment environment by lowering the cost of doing business. Growth rates of 7.6% in FY2006 and 7.8% in FY2007 are forecast. The annual average growth rate over 2006–2010 is unlikely to exceed 8–8.5%. Economic performance The Indian economy achieved a gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate of 8.1% in FY2005 (1 April 2005–31 March 2006). On the expenditure side, the economy was lifted by broad-based domestic demand growth. 2.16.1 Business confidence index While aggregate expenditure data have not yet been released, consumption May 1993 = 100 160 growth is estimated at 8.0%, driven by a good monsoon, which supported 150 rural incomes. Gross fixed capital formation grew at an estimated rate 140 of 8.5%, reflecting rising investor confidence (Figure 2.16.1) in the face 130 of strongly entrenched demand growth and as a consequence of the 120 expansion in credit and companies’ initial public offerings. -

Logistics System and Process in Express Delivery Service Companies

LOGISTICS SYSTEM AND PROCESS IN EXPRESS DELIVERY SERVICE COMPANIES Hanzheng Zhu Bachelor’s Thesis May, 2010 Degree Programme in Logistics Engineering Technology, Communication and Transport DESCRIPTION Author(s) Type of publication Date Bachelor´s Thesis 25/05/2010 Zhu Hanzheng Pages Language 53+7 English Confidential Permission for web ( ) Until publication ( X ) Title LOGISTICS SYSTEM AND PROCESS IN EXPRESS DELIVERY SERVICE COMPANIES Degree Programme Degree Programme in Logistics Engineering Tutor(s) Salmijärvi Olli Assigned by Xi’an Express Mail Service Logistics Company of China Post Abstract Express delivery services (EDS), as a young industry, are currently experiencing a rapid growth to fulfill the increasing demand. With the aims of being fast, safe, controllable and traceable, EDS companies have developed a quite different logistics network and systems in their logistics process. The purpose of this study was to describe EDS network models, like the spoke-hub paradigm, as well as the way of EDS processing. It was also studied how much of advanced and automated technologies and methods, like geographical information system, are used for optimizing the network, accelerating the delivery speed and improving services. The whole logistics chain of EDS was to be presented in this thesis. Express Mail Service (EMS), a large Chinese express delivery corporation, plays an important role in this market. Its significant part, EMS of China Post corporation, is now experiencing hard competition. This thesis went deeper inside the Chinese EMS company and found reasons that have led to competitive advantages and weaknesses through using the SWOT analysis. The research material included a lot of information and data from EMS company and its market and from the author’s internship experience. -

Allocation of Postal Circle to Candidates Recommended by SSC

No. W-04-7/2018-SPB-I Govemment of India Ministry of Communications Department of Posts Dak Bhawan, Sansad Marg New Delhi, dated 11.06.2018 Subject:-Allocation of Postal Circle to candidates recommended by SSC for appointment as Postal Assistant / Sorting Assistant on the basis of Combined Higher Secondary Level Examination, 2016. Attention is invited to Department of Posts letter No. W-04-712017-SPB-I dated 07.03.2018 read with letter dated 14.05.2018 wherein candidates recommended by Staff Selection Commission (SSC), on the basis of Combined Higher Secondary Level (CHSL) Examination,2016, for appointment as Postal Assistant / Sorting Assistant, were advised to submit their preference / option for allocation of Postal Circles by email and Speed Post / Register Post. 2. Although SSC has recommended 3295 candidates for appointment as Postal Assistant / Sorting Assistant on the basis of CHSL Examination,2016; SSC has confirmed nomination of 3215 candidates and their dossiers have been received till date. Postal Circles have been allocated to all 3295 cmdidates, as per the criteria stipulated in aforesaid letter dated 07.03.2018, irrespective of the status of receipt of dossiers in Department of Posts. All those candidates whose dossiers are yet to be forwarded by the SSC, their candidature shall be subject to confirmation of nomination / forwarding of dossiers by SSC and they shall have no claim over the appointment to the said posts in the Department of Posts. Consequently, in case of candidates whose nominations are yet to be confirmed / dossiers are yet to be forwarded by SSC, the appointing authority shall not issue offer of appointment till confirmation of nomination by SSC and receipt of dossiers by Department of Posts. -

Edited by Accelerating Growth and Job

2 Cont’d from front flap ‘In this excellent volume, Ejaz Ghani and Sadiq Ahmed have invited GHANI Accelerating Growth and the world’s leading scholars to apply their talents to understanding the Timely and relevant in the context of the economies of South Asia. They cover a wide range of topics. Scholars AHMED Job Creation in South Asia ongoing global crisis, this book will be useful interested in South Asia will find the volume most illuminating.’ for policymakers, NGOs, development agencies, —Arvind Panagariya, Columbia University In recent times, South Asia has attracted global and industry strategists. It will also be of interest attention for demonstrating rapid growth. What to students and scholars of economics and ‘The importance of this book cannot be overestimated. It powerfully explores is not so well known is that this is the least the link between regional integration, economic growth, and job creation. Public Disclosure Authorized South Asian studies. integrated region in the world. South Asia has It has several imaginative proposals that can be debated and discussed. It is opened its door to the rest of the world but ambitious but not unmindful of the difficult political economy of the region …’ Accelerating Growth Ejaz Ghani is Economic Adviser, Poverty remains closed to its neighbours. Poor market —Pratap Bhanu Mehta, Centre for Policy Research Reduction and Economic Management Job Creation in South Asia integration, weak connectivity, and a history Accelerating Growth and and Job Creation of conflict have created ‘two South Asias’. The Department, South Asia Region, The World Bank. ‘This book … usefully turns the spotlight away from India to the regional context. -

Government Response to Self-Determination Movements: a Case Study Comparison in India

GOVERNMENT RESPONSE TO SELF-DETERMINATION MOVEMENTS: A CASE STUDY COMPARISON IN INDIA By Pritha Hariharan Submitted to the graduate degree program in MA Global and International Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson: John James Kennedy ________________________________ Committee Member: MichaelWuthrich ________________________________ Committee Member: Eric Hanley Date Defended: November 18th 2014 The Thesis Committee for Pritha Hariharan certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: GOVERNMENT RESPONSE TO SELF-DETERMINATION MOVEMENTS: A CASE STUDY COMPARISON IN INDIA ________________________________ Chairperson: John James Kennedy Date approved: November 18th 2014 ii Abstract The Indian government’s response to multiple separatist and self-determination movements the nation has encountered in its sixty-six year history has ranged from violent repression to complete or partial accommodation of demands. My research question asks whether the central government of India’s response to self-determination demands varies based on the type of demand or type of group. The importance of this topic stems from the geopolitical significance of India as an economic giant; as the largest and fastest growing economy in the subcontinent, the stability of India as a federal republic is crucial to the overall strength of the region. While the dispute between India and Pakistan in the state of Kashmir gets international attention, other movements that are associated with multiple fatalities and human rights abuses are largely ignored. I conduct a comparative case study analysis comparing one movement each in the states of Tamil Nadu, Punjab, Assam, Kashmir, and Mizoram; each with a diverse set of demands and where agitation has lasted more than five years.