FOTW: the Ultimate Vexillological Encyclopedia Or an Ephemeral Web Site?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE LION FLAG Norway's First National Flag Jan Henrik Munksgaard

THE LION FLAG Norway’s First National Flag Jan Henrik Munksgaard On 27 February 1814, the Norwegian Regent Christian Frederik made a proclamation concerning the Norwegian flag, stating: The Norwegian flag shall henceforth be red, with a white cross dividing the flag into quarters. The national coat of arms, the Norwegian lion with the yellow halberd, shall be placed in the upper hoist corner. All naval and merchant vessels shall fly this flag. This was Norway’s first national flag. What was the background for this proclamation? Why should Norway have a new flag in 1814, and what are the reasons for the design and colours of this flag? The Dannebrog Was the Flag of Denmark-Norway For several hundred years, Denmark-Norway had been in a legislative union. Denmark was the leading party in this union, and Copenhagen was the administrative centre of the double monarchy. The Dannebrog had been the common flag of the whole realm since the beginning of the 16th century. The red flag with a white cross was known all over Europe, and in every shipping town the citizens were familiar with this symbol of Denmark-Norway. Two variants of The Dannebrog existed: a swallow-tailed flag, which was the king’s flag or state flag flown on government vessels and buildings, and a rectangular flag for private use on ordinary merchant ships or on private flagpoles. In addition, a number of special flags based on the Dannebrog existed. The flag was as frequently used and just as popular in Norway as in Denmark. The Napoleonic Wars Result in Political Changes in Scandinavia At the beginning of 1813, few Norwegians could imagine dissolution of the union with Denmark. -

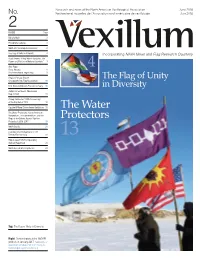

Vexillum, June 2018, No. 2

Research and news of the North American Vexillological Association June 2018 No. Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine de vexillologie Juin 2018 2 INSIDE Page Editor’s Note 2 President’s Column 3 NAVA Membership Anniversaries 3 The Flag of Unity in Diversity 4 Incorporating NAVA News and Flag Research Quarterly Book Review: "A Flag Worth Dying For: The Power and Politics of National Symbols" 7 New Flags: 4 Reno, Nevada 8 The International Vegan Flag 9 Regional Group Report: The Flag of Unity Chesapeake Bay Flag Association 10 Vexi-News Celebrates First Anniversary 10 in Diversity Judge Carlos Moore, Mississippi Flag Activist 11 Stamp Celebrates 200th Anniversary of the Flag Act of 1818 12 Captain William Driver Award Guidelines 12 The Water The Water Protectors: Native American Nationalism, Environmentalism, and the Flags of the Dakota Access Pipeline Protectors Protests of 2016–2017 13 NAVA Grants 21 Evolutionary Vexillography in the Twenty-First Century 21 13 Help Support NAVA's Upcoming Vatican Flags Book 23 NAVA Annual Meeting Notice 24 Top: The Flag of Unity in Diversity Right: Demonstrators at the NoDAPL protests in January 2017. Source: https:// www.indianz.com/News/2017/01/27/delay-in- nodapl-response-points-to-more.asp 2 | June 2018 • Vexillum No. 2 June / Juin 2018 Number 2 / Numéro 2 Editor's Note | Note de la rédaction Dear Reader: We hope you enjoyed the premiere issue of Vexillum. In addition to offering my thanks Research and news of the North American to the contributors and our fine layout designer Jonathan Lehmann, I owe a special note Vexillological Association / Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine of gratitude to NAVA members Peter Ansoff, Stan Contrades, Xing Fei, Ted Kaye, Pete de vexillologie. -

Lista Dei (Nicknames)

Lista dei (nicknames) Belgio - Driekleur, Tricolore o Flanders: De Vlaamse Leeuw o Wallonia: Le Coq Hardi Brasile: auriverde Canada: o Maple Leaf Flag o Unifolié (French) o Quebec: Fleurdelysé Cina: Five Stars Red Flag o Older Chinese flag nicknames o National Flag pre-1912: Dragon Flag o National Flag 1912-1928: Five Coloured Flag o Army Flag 1912-1928: 18 Stars Flag o Tibet: Snow Mountain and Lions Flag Colombia: tricolor o Colombian subdivisions o Cartagena: cuadrilonga o Barranquilla: cuadrilonga Croazia: Trobojnica (tricolor), Crven-Bijeli-Plavi (red white blue), Barjak (flag); the chequy shield: S'ahovnica (chessboard) Cuba: La Estrella Solitaria (the lonely star) Danimarca: Dannebrog Finlandia: Siniristilippu (flag with a blue cross) Francia: Tricolore o Bretagne: Gwenn Ha Du (white and black) Faroer Islands Merkið Germania: Schwarz-Rot- Giappone: Hinomaru (sun disc flag) o Naval ensign: Rising Sun Flag Olanda: Princenvlag, Oranje-Blanje-Bleu (orange white blue) o States-General flag of the Republic of United Netherlands: Statenvlag, Generaliteitsvlag Frisia del nord: Göljn-Rüuuml; Gold (black red gold) o Bavaria: Rautenflagge (Lozenges flag) o Bremen: Speckflagge o Third Reich: Hakenreuzflagge (swastika flag) o Weimar Republic: Schwarz-Rot-Mostrich (Black-Red-Mustard [derogatory nickname used by anti-democratic groups]) Germania dell’est - Spalterflagge (derogatory term) Grecia: Galanolefki (the blue-and-white) Guyana: Golden Arrow Indonesia: Sang Saka (Lofty Bicolor, off.), Merah Putih (red white) Italia: Tricolore (tricolor) Norwegia o Sweden and Norway (1844): Herring Salad (union of the flag) Polonia: bialo-czerwona (white-red) Pirati: Jolly Roger Portogallo: Verde E Rubra, Verde-Rubra (green and red) Porto Rico: La Monoestrellada (The Single Star Flag) Russia: Andreevsky (St. -

Flag Research Quarterly, September 2017, No. 14

FLAG RESEARCH QUARTERLY REVUE TRIMESTRIELLE DE RECHERCHE EN VEXILLOLOGIE SEPTEMBER / SEPTEMBRE 2017 No. 14 A research publication of the North American The Aztec Heritage of Vexillological Association-Une publication de recherche de l‘Association nord-américaine de vexillologie the Mexican Flag By John M. Hartvigsen Right: Current flag of Mexico. Source: The Mexican flag is not only recognizable and effec- http://encircleworldphotos.photoshelter.com/image/ tive, but it is also beautiful and beloved. In 2008, 20 I0000ERYcGfnhpag Minutos, a free Spanish language newspaper, ran a Background watermark: Golden-linear version survey contest to pick the “most beautiful flag in the of coat of arms of Mexico, adopted 1968. world.” Although the publication is based in Spain, the contest was picked up Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coat_of_arms_of_ Mexico#/media/File:Coat_of_arms_of_Mexico_(golden_ by other publications in Latin America. One of a series of “best-of surveys,” the linear).svg contest asked readers to rate the flags of 140 nations. Although this was a self- selecting sample and not a scientific survey, it was an interesting outgrowth of the phenomenon of flags. The contest attracted 1,920,000 entry ballots, which was three times the number of participant entries that are normally attracted by similar “best-of contests.” The article’s title announced the results dramati- cally: “Mexico sweeps the most beautiful flag in the world list.” Mexico’s flag received 901,607 points, or 47% of the vote.1 This, of course, does not prove that the Mexican flag is actually the most beautiful flag in the world, but this and extensive anecdotal evidence demonstrates that the flag “works” and is a beloved banner. -

The Negritude Movements in Colombia

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses October 2018 THE NEGRITUDE MOVEMENTS IN COLOMBIA Carlos Valderrama University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Folklore Commons, Other Political Science Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Valderrama, Carlos, "THE NEGRITUDE MOVEMENTS IN COLOMBIA" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1408. https://doi.org/10.7275/11944316.0 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/1408 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEGRITUDE MOVEMENTS IN COLOMBIA A Dissertation Presented by CARLOS ALBERTO VALDERRAMA RENTERÍA Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts-Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SEPTEMBER 2018 Sociology © Copyright by Carlos Alberto Valderrama Rentería 2018 All Rights Reserved THE NEGRITUDE MOVEMENTS IN COLOMBIA A Dissertation Presented by CARLOS ALBERTO VALDERRAMA RENTERÍA Approved as to style and content by __________________________________________ Agustin Laó-Móntes, Chair __________________________________________ Enobong Hannah Branch, Member __________________________________________ Millie Thayer, Member _________________________________ John Bracey Jr., outside Member ______________________________ Anthony Paik, Department Head Department of Sociology DEDICATION To my wife, son (R.I.P), mother and siblings ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I could not have finished this dissertation without the guidance and help of so many people. My mentor and friend Agustin Lao Montes. My beloved committee members, Millie Thayer, Enobong Hannah Branch and John Bracey. -

Flags and Banners

Flags and Banners A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton Contents 1 Flag 1 1.1 History ................................................. 2 1.2 National flags ............................................. 4 1.2.1 Civil flags ........................................... 8 1.2.2 War flags ........................................... 8 1.2.3 International flags ....................................... 8 1.3 At sea ................................................. 8 1.4 Shapes and designs .......................................... 9 1.4.1 Vertical flags ......................................... 12 1.5 Religious flags ............................................. 13 1.6 Linguistic flags ............................................. 13 1.7 In sports ................................................ 16 1.8 Diplomatic flags ............................................ 18 1.9 In politics ............................................... 18 1.10 Vehicle flags .............................................. 18 1.11 Swimming flags ............................................ 19 1.12 Railway flags .............................................. 20 1.13 Flagpoles ............................................... 21 1.13.1 Record heights ........................................ 21 1.13.2 Design ............................................. 21 1.14 Hoisting the flag ............................................ 21 1.15 Flags and communication ....................................... 21 1.16 Flapping ................................................ 23 1.17 See also ............................................... -

Grb I Zastava

Grb i Zastava Glasnik Hrvatskog grboslovnog i zastavoslovnog društva Broj 0, Godina 0. Bulletin of the Croatian Heraldic & Vexillologic Association Zagreb, listopad 2006. Osnivačka skupština HGZD snivačka skupština HGZD održana Oje 4. svibnja 2006. godine u svečanoj dvorani Hrvatskog povijesnog muzeja, uz prisustvo tridesetak sudionika. Time je i formalno osnovano Hrvatsko grboslovno i zastavoslovno društvo (HGZD), kako je nakon diskusije Sa osnivačke skupštine (gore, lijevo). From the skupština odlučila da će se Društvo zvati. Establishing Assembly (top, left). Foto Boris Priester. Cilj osnivanja Društva je unaprjeđenje heraldike (grbopisa i grboslovlja) i Following it, in accordance with the Statutes veksilologije (zastavopisa i zastavoslovlja) the institutions of the association were elected. kao pomoćnih povijesnih znanosti i kao The newly elected president presented the grana suvremene primijenjene umjetnosti, agenda for the current year and the long term poticanje i razvijanje šireg interesa za The CHVA Establishing Assembly guidelines of the Association. After the working heraldiku i veksilologiju te srodne session, the participants continued the meeting znanstvene discipline kao što su sfragistika, The Establishing Assembly of CHVA was with a modest snack in the doorways of the faleristika i genealogija te očuvanja held on the 4th May 2006 in the Ceremonial Hall Croatian History Museum. heraldičke i veksilološke baštine posebice of the Croatian History Museum, with some thirty na području Republike Hrvatske. participants. Thus the Croatian Heraldic and Kao uvod u rad skupštine prikazana je Vexillologic Association (CHVA) was formally prezenacija s presjekom hrvatske established. heraldičke i veksilološke baštine u trajanju The goal of the establishment of the od dvadesetak minuta, nakon čega se prešlo association is the promotion of the heraldry and na radni dio skupa. -

![[Flags of Europe]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1836/flags-of-europe-1771836.webp)

[Flags of Europe]

Flags of Europe Item Type Book Authors McGiverin, Rolland Publisher Indiana State University Download date 06/10/2021 08:52:56 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10484/12199 Flag Flags of Europe: A Bibliography Rolland McGiverin Indiana State University 2016 i Contents Country 14 Flags of Europe: Andorra 15 European Union 1 Country 15 NATO 1 Andorra la Vella 15 European Contenant 1 Parish 15 Armed forces 6 Armenia 15 Merchant marine 9 Country 15 Navy 10 Asti 17 Abkhazia 11 Country 17 Partially Recognized State 11 Austria 17 Adjara 12 Country 17 Autonomous Republic in Georgia 12 Nagorno-Karabakh 19 Region 19 Aland 12 Autonomous part of Finland 12 Austro-Hungarian Empire 19 Political 12 Country 19 Ethnic 19 Albania 13 Navy 19 Country 13 Belarus 20 Alderney 13 Country 20 British Crown dependency 13 Air Force 21 Amalfi Republic 13 Armed forces 21 Country 13 Ethnic 21 Armed forces 14 Government 22 Ethnic 14 Azerbaijan 22 Political 14 Country 22 Tirana 14 Ethnic 22 County 14 Political 23 Cities and towns 14 Talysh-Mughan 23 Region 23 Anconine Republic 14 Grodno 23 ii Region 23 Cospaia, Republic 33 Barysaw 24 Country 33 Gomel 24 Krasnasielski 24 Croatia 33 Smarhon 24 Country 33 Hrodna 24 Region 24 Ethnic 33 Dzyatlava 24 Karelichy 24 Cyprus 34 Minsk 25 Country 34 Region 25 North Cyprus 34 Minsk 25 Nicosia 34 Mogilev 25 Czech Republic 34 Belgium 25 Country 34 Country 25 Cities and Towns 35 Armed forces 26 Prague 35 Ethnic 27 Czechoslovakia 35 Labor 27 Country 35 Navy 28 Armed forces 37 Political 28 Cities and Towns 37 Religion 29 Ethnic 38 Provinces -

Four Forgotten Norwegian Ensigns Jan Oskar Engene

Four Forgotten Norwegian Ensigns Jan Oskar Engene Abstract Standard narratives of Norwegian flag history usually discuss only two specially marked ensigns: the customs and postal ensigns, both based on the swallow-tailed and tongued state ensign of Norway. These were the two ensigns permitted under the 1898 Flag Act that removed the Swedish-Norwegian union mark from civic and state flags and ensigns of Norway. Yet in the last years of the union between Norway and Sweden several more specially marked ensigns existed. At the Yokohama ICV in 2009 I documented the ensign of the Lighthouse Service. In this paper attention is devoted to four more ensigns: those of the State Port Authority, the Port of Kristiania, the Christiania Harbour Police, and the Fisheries Inspection Service. A secondary written description is available for the two port ensigns, though no legal basis has been found for them. The legal basis is available for the Christiania Harbour Police and the Fisheries Inspection Service ensigns; the latter is also illustrated in international flag books of the late 1800s. All four ensigns would have been made defunct by the 1898 Flag Act, though sources indicate the continued use of the Christiania Harbour Police ensign and photographic evidence shows the Fisheries Inspection Service ensign flying as late as 1936. Redrawing of the ensign of the Fisheries Inspection Service, 1936 Proceedings of the 24th International Congress of Vexillology, Washington, D.C., USA 1–5 August 2011 © 2011 North American Vexillological Association (www.nava.org) 192 Four Forgotten Norwegian Ensigns In the standard narrative of Norwegian flag history, attention is usually devoted to the flag dispute of the 19th century and the struggle to get rid of the union mark, symbol of the union between Norway and Sweden. -

Post-Colonial Relationships on the Flagpole

Middle States Geographer, 2018, 51: 77-86 IMPERIAL BANNERS? POST-COLONIAL RELATIONSHIPS ON THE FLAGPOLE Noah Anders Carlen Department of Geography and Environmental Engineering United States Military Academy West Point, NY 10997 ABSTRACT: This research was conducted to examine trends in the flags of post-colonial nations around the world, grouping them by the empire to which they belonged. A flag is the preeminent symbol of a nation, typically representing a country’s most important values. As empires broke up, dozens of new countries struggled to find and establish common identities. As expected, countries that went through similar colonial experiences produced flags with similar values, reflecting their history with imperialism. This research compiled data of what was represented on the national flag of every former colonial country and tallied how many from each empire (Portuguese, Spanish, French, and British) included certain values or ideas. The resulting information showed that the institution of independence was much more prominent in Portuguese and Spanish countries than it was in French and British countries, caused by greater struggles during their colonial period. This project reveals how flags can be used collectively as a powerful tool to analyze geographic and historical trends, using national symbols as a point of comparison between countries across the globe. Keywords: Flags, vexillology, colonialism, identity INTRODUCTION Flags are strongly connected to the concepts of patriotism and national identity, and as such they reveal a lot about who they represent. Like any symbol, they are dynamic over time, depicting only a snippet of a people’s values and how they define their country. -

Colombia Curriculum Guide 090916.Pmd

National Geographic describes Colombia as South America’s sleeping giant, awakening to its vast potential. “The Door of the Americas” offers guests a cornucopia of natural wonders alongside sleepy, authentic villages and vibrant, progressive cities. The diverse, tropical country of Colombia is a place where tourism is now booming, and the turmoil and unrest of guerrilla conflict are yesterday’s news. Today tourists find themselves in what seems to be the best of all destinations... panoramic beaches, jungle hiking trails, breathtaking volcanoes and waterfalls, deserts, adventure sports, unmatched flora and fauna, centuries old indigenous cultures, and an almost daily celebration of food, fashion and festivals. The warm temperatures of the lowlands contrast with the cool of the highlands and the freezing nights of the upper Andes. Colombia is as rich in both nature and natural resources as any place in the world. It passionately protects its unmatched wildlife, while warmly sharing its coffee, its emeralds, and its happiness with the world. It boasts as many animal species as any country on Earth, hosting more than 1,889 species of birds, 763 species of amphibians, 479 species of mammals, 571 species of reptiles, 3,533 species of fish, and a mind-blowing 30,436 species of plants. Yet Colombia is so much more than jaguars, sombreros and the legend of El Dorado. A TIME magazine cover story properly noted “The Colombian Comeback” by explaining its rise “from nearly failed state to emerging global player in less than a decade.” It is respected as “The Fashion Capital of Latin America,” “The Salsa Capital of the World,” the host of the world’s largest theater festival and the home of the world’s second largest carnival. -

Contemporary Flags of the Ukrainian Regions: Old Traditions and New Designs

Contemporary flags of the Ukrainian regions: Old traditions and new designs Andriy Grechylo Abstract Ukraine consists of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and 24 oblasts (regions or provinces). The new law on local self-governments, adopted by the Verkhovna Rada (Parliament) of Ukraine in 1997, allowed local authorities to confirm the coats of arms, flags, and other symbols of oblasts, rayons (districts), cities, towns, and villages. Over the last six years, all oblasts have adopted their own symbols. Most of them have already adopted regional flags. Many of these flags have old historical signs and colours (Volyn, Ivano-Frankivsk, Lviv, etc.), but some oblasts have chosen new designs (Donetsk, Cherkasy, Kherson, and others). Ukraine is divided into 25 administrative territories — 24 oblasts (provinces or re- gions) and the Autonomous Republic of Crimea. Two cities, Kyiv and Sevastopol, have a special, national status. The oblast borders have remained unchanged since 1959, when Drohobych oblast was joined to the Lviv oblast (Fig. 1). After the disintegration of the Ruthenian Kingdom (Galician-Volynian State) in the middle of the 14th c., the Ukrainian lands were divided among various neighbour- ing countries. During this time the arms of separate administrative territories were used. When Ukraine was absorbed into the USSR, none of the oblasts possessed their own arms or flag. Only after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the declaration of Ukrainian independence did a process of the formation of symbols of administrative territories begin. The first regional coat of arms was ratified for the Transcarpathian (Zakarpattya) oblast in December 1990. In 1992 the symbols of Crimea, which received the status of an autonomous republic, were adopted.