33559613.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Phase 5 Report 2017-2018

Maine-New Brunswick Cultural Initiative Task Force Phase 5 Report 2017-2018 Darren Emenau Prepared by the Department of Tourism, Heritage & Culture [email protected] 1 CONTENTS ❖ Introduction ❖ Projects and Events o 2017 o 2018 ❖ Overview Document ❖ Conclusion 2 Introduction Phase Report This Phase Report was developed by the New Brunswick Department of Tourism, Heritage and Culture in collaboration with the members of the Maine-New Brunswick Cultural Task Force to highlight initiatives and cross-border collaborative projects over the years of 2017 and 2018. The information included in this report results from the 2010 Memorandum of Understanding between the State of Maine and the Province of New Brunswick. This report is intended to elaborate on important initiatives and partnership events undertaken by the members of the Maine-New Brunswick Cultural Initiative that reflect the continued meaningful collaborative relationship between artists, organization leaders, communities, and cultural stakeholders from Maine and New Brunswick. The Phase I Report (December 2010), Phase 2 Report (October 2011), Phase 3 Report (October 2014), and Phase 4 Report (December 2016) encompass an overview of the status, priorities, and possibilities outlined in the original agreement. Each report identifies steps taken and tangible initiatives being considered or implemented. Task Force Summary A Memorandum of Understanding Between the State of Maine and the Province of New Brunswick was signed in July 2010 by the former Premier of New Brunswick, the Honorable Shawn Graham, and the former Governor of the State of Maine, Governor John Baldacci with the mandate to “Enhance the Mutual Benefits of Maine/New Brunswick Cultural Relations through the Establishment of a Maine/New Brunswick Cultural Initiative”. -

6 Inspiring Cajun Musicians

LeadingLadies 6 INSPIRING CAJUN MUSICIANS In what has become our now annual music their voices have been heard and met with guide, we decided to do something a little praise – even Grammy nominations. All six different. Rather than focus on venues, clubs of these women are carrying on the tradition and places to go, we chose to focus on faces of their Cajun ancestors and bringing it to look for – and more importantly, voices to into the future, and we hope that the trend hear. In the music industry in general – and of women leading their own bands will gain especially when it comes to Cajun music, momentum as they continue to inspire others. women are outnumbered by men. Fortunately, That, we think, is worth singing about. By Michael Patrick Welch \\ Photos by Romero & Romero acadianaprofile.com | 31 gigs as Petite et les Patates (Little and the AT THE AGE OF 18, Potatoes), a quieter three-piece traditional musician Jamie Lynn Fontenot was Cajun band. overtaken by the desire to learn Cajun Along with accordion player Jacques French. “My grandparents, Mary ‘Mimi’ fontenotBoudreaux, Petite et les Patates also often Fontenot and John ‘Toe’ Fontenot, from features Fontenot's husband, French fiddle Opelousas are great, really strong Cajun player Samuel Giarrusso, who moved to speakers,” says Fontenot from her home in Louisiana in 2012 from France to be near his Lafayette. “My siblings and I wanted them father, also a Cajun French musician. “Petite to teach us Cajun French, so she would play et les Patates is actually a constantly rotating me all these old Cajun vinyl records, and band, where I am the only constant,” says she’d tell me the stories the singers were Fontenot. -

RNN-Based Generation of Polyphonic Music and Jazz Improvisation

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2018 RNN-Based Generation of Polyphonic Music and Jazz Improvisation Andrew Hannum University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Artificial Intelligence and Robotics Commons, and the Music Pedagogy Commons Recommended Citation Hannum, Andrew, "RNN-Based Generation of Polyphonic Music and Jazz Improvisation" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1532. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1532 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. RNN-based generation of polyphonic music and jazz improvisation A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Daniel Felix Ritchie School of Engineering and Computer Science In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Andrew Hannum November 2018 Advisor: Mario A. Lopez c Copyright by Andrew Hannum 2018 All Rights Reserved Author: Andrew Hannum Title: RNN-based generation of polyphonic music and jazz improvisation Advisor: Mario A. Lopez Degree Date: November 2018 Abstract This paper presents techniques developed for algorithmic composition of both polyphonic music, and of simulated jazz improvisation, using multiple novel data sources and the character-based recurrent neural network architecture char- rnn. In addition, techniques and tooling are presented aimed at using the results of the algorithmic composition to create exercises for musical pedagogy. -

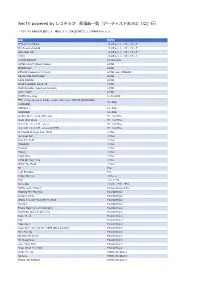

Rectv Powered by レコチョク 配信曲 覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」 )

RecTV powered by レコチョク 配信曲⼀覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」⾏) ※2021/7/19時点の配信曲です。時期によっては配信が終了している場合があります。 曲名 歌手名 アワイロサクラチル バイオレント イズ サバンナ It's Power of LOVE バイオレント イズ サバンナ OH LOVE YOU バイオレント イズ サバンナ つなぐ バイオレント イズ サバンナ I'M DIFFERENT HI SUHYUN AFTER LIGHT [Music Video] HYDE INTERPLAY HYDE ZIPANG (Japanese Version) HYDE feat. YOSHIKI BELIEVING IN MYSELF HYDE FAKE DIVINE HYDE WHO'S GONNA SAVE US HYDE MAD QUALIA [Japanese Version] HYDE LET IT OUT HYDE 数え切れないKiss Hi-Fi CAMP 雲の上 feat. Keyco & Meika, Izpon, Take from KOKYO [ACOUSTIC HIFANA VERSION] CONNECT HIFANA WAMONO HIFANA A Little More For A Little You ザ・ハイヴス Walk Idiot Walk ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン(ライヴ) ザ・ハイヴス If I Could Change Your Mind ハイム Summer Girl ハイム Now I'm In It ハイム Hallelujah ハイム Forever ハイム Falling ハイム Right Now ハイム Little Of Your Love ハイム Want You Back ハイム BJ Pile Lost Paradise Pile I Was Wrong バイレン 100 ハウィーD Shine On ハウス・オブ・ラヴ Battle [Lyric Video] House Gospel Choir Waiting For The Sun Powderfinger Already Gone Powderfinger (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderfinger Sunsets Powderfinger These Days [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Stumblin' [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Take Me In Powderfinger Tail Powderfinger Passenger Powderfinger Passenger [Live At The 1999 ARIA Awards] Powderfinger Pick You Up Powderfinger My Kind Of Scene Powderfinger My Happiness Powderfinger Love Your Way Powderfinger Reap What You Sow Powderfinger Wake We Up HOWL BE QUIET fantasia HOWL BE QUIET MONSTER WORLD HOWL BE QUIET 「いくらだと思う?」って聞かれると緊張する(ハタリズム) バカリズムと アステリズム HaKU 1秒間で君を連れ去りたい HaKU everything but the love HaKU the day HaKU think about you HaKU dye it white HaKU masquerade HaKU red or blue HaKU What's with him HaKU Ice cream BACK-ON a day dreaming.. -

Here It Might, As Long As It’S Somewhere Worth Traveling

BRUCE ROBISON Bruce Robison has been making music professionally for decades. He still discusses his craft with so much enthusiasm he sounds almost like a kid raving about superheroes. That infectious energy is evident in every note of his new album, Bruce Robison & the Back Porch Band, as well as his new project, The Next Waltz, a blossoming community of artists, fans and friends gathering both virtually and at his recording studio in Lockhart, just outside of Austin. In both cases, the point is to celebrate country music’s rich traditions while giving creativity free rein to go where it might, as long as it’s somewhere worth traveling. It’s also about celebrating Robison’s “love of the craft of song.” “Writing is where it all starts for me,” he explains. “Whether it’s my writing, or songs I want to do with somebody else. I love the mechanics of it; how simple it can be.” Keeping it simple — and organic — was the guiding principle behind the latest album, a collection of Robison originals, co-writes and covers that capture country’s most beloved stylistic elements: good-time, lighthearted romps (“Rock and Roll Honky Tonk Ramblin’ Man”; “Paid My Dues”) and wistful, sometimes bittersweet ballads (“Long Time Coming”; “Still Doin’ Time”). But even the Who’s “Squeezebox” — which Robison calls “a great country song by some English dudes” — shows up, in a lively version dressed with cajun fiddle by Warren Hood and acoustic guitar and harmonies by Robison’s wife, Kelly Willis. Hood is one of a hand-picked crew of regulars tapped for Next Waltz recording sessions with Jerry Jeff Walker, Randy Rogers, Jack Ingram, Rodney Crowell, Willis, Hayes Carll, Turnpike Troubadours, Sunny Sweeney, Reckless Kelly and others. -

Acadiens and Cajuns.Indb

canadiana oenipontana 9 Ursula Mathis-Moser, Günter Bischof (dirs.) Acadians and Cajuns. The Politics and Culture of French Minorities in North America Acadiens et Cajuns. Politique et culture de minorités francophones en Amérique du Nord innsbruck university press SERIES canadiana oenipontana 9 iup • innsbruck university press © innsbruck university press, 2009 Universität Innsbruck, Vizerektorat für Forschung 1. Auflage Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Umschlag: Gregor Sailer Umschlagmotiv: Herménégilde Chiasson, “Evangeline Beach, an American Tragedy, peinture no. 3“ Satz: Palli & Palli OEG, Innsbruck Produktion: Fred Steiner, Rinn www.uibk.ac.at/iup ISBN 978-3-902571-93-9 Ursula Mathis-Moser, Günter Bischof (dirs.) Acadians and Cajuns. The Politics and Culture of French Minorities in North America Acadiens et Cajuns. Politique et culture de minorités francophones en Amérique du Nord Contents — Table des matières Introduction Avant-propos ....................................................................................................... 7 Ursula Mathis-Moser – Günter Bischof des matières Table — By Way of an Introduction En guise d’introduction ................................................................................... 23 Contents Herménégilde Chiasson Beatitudes – BéatitudeS ................................................................................................. 23 Maurice Basque, Université de Moncton Acadiens, Cadiens et Cajuns: identités communes ou distinctes? ............................ 27 History and Politics Histoire -

Maine State Legislature

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from electronic originals (may include minor formatting differences from printed original) MAINE STATE CULTURAL AFFAIRS COUNCIL 2012 Annual Report Maine Arts Commission Maine Historic Preservation Commission Maine Historical Society Maine Humanities Council Maine State Library Maine State Museum Submitted to the Joint Committee on Education and Cultural Affairs June 2013 Maine State Cultural Affairs Council Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 3 Maine State Cultural Affairs Council History and Purpose ............................................................... 3 MAINE STATE CULTURAL AFFAIRS COUNCIL .................................................................... 5 Purpose and Organization: .................................................................................................................... 5 Program / Acquisitions: ........................................................................................................................... 5 Accomplishments:.......................................................................................................................................5 Program Needs: ........................................................................................................................................6 -

Abstracts (Pdf)

2004 ABSTRACTS / RÉSUMÉS 2004 Abedi, Amir and Schneider - Adapt, or Die! Organizational Change in Office-Seeking Anti-Political Establishment Parties There is relatively little work dealing with anti-political establishment (APE) parties in the extensive party organization literature. Organizational change within that party type remains an under-researched area even as a number of APE parties has joined governments in several West European countries. Government participation should put stress on APE parties because they differ from mainstream parties both in terms of policy profiles and of their organizational make-up. Being in government should foster more moderate policy positions and organizational structures more closely resembling those of mainstream parties. APE parties that fail to adapt may be less successful in their attempts to establish themselves permanently as (potentially) governing parties. We examine these issues by focusing on Germany, which not only provides examples of APE parties that have become serious contenders for government participation but also formations that have succeeded in gaining access to government but not in establishing themselves long-term. Despite growing political cynicism, APE parties have faced considerable hurdles in Germany. Organizationally challenges often proved at least as important - and in many cases, fatal - as the hurdles built into the electoral system. These challenges stemmed from conflicts between the very rationale of being anti-establishment on the one hand and the objective of government participation on the other. Using the most similar cases design, our paper compares the experiences of successful and unsuccessful cases of organizational change. This should help us in answering the larger theoretical question of whether APE parties can transform themselves into establishment parties, and if so, which factors are most important in predicting the likelihood of successful organizational adaptation. -

American Folklife Center & Veterans History Project

AMERICAN FOLKLIFE CENTER & VETERANS HISTORY PROJECT Library of Congress Annual Report, Fiscal Year 2010 (October 2009-September 2010) The American Folklife Center (AFC), which includes the Veterans History Project (VHP), had another productive year. Over 150,000 items were acquired, and over 127,000 items were processed by AFC's archive, which is the country’s first national archive of traditional culture, and one of the oldest and largest of such repositories in the world. VHP continued making strides in its mission to collect and preserve the stories of our nation's veterans, acquiring 7,408 collections (13,744 items) in FY2010. The VHP public database provided access to information on all processed collections; its fully digitized collections, whose materials are available through the Library’s web site to any computer with internet access, now number over 8,000. Together, AFC and VHP acquired a total of 168,198 items in FY2010, of which 151,230 were Non-Purchase Items by Gift. AFC and VHP processed a total of 279,298 items in FY2010, and cataloged 54,758 items. AFC and VHP attracted just under five million “Page Views” on the Library of Congress website, not counting AFC’s popular “American Memory” collections. ARCHIVAL ACCOMPLISHMENTS KEY ACQUISITIONS American Voices with Senator Bill Bradley (AFC 2010/004) 117 born-digital audio recordings of interviews from the radio show American Voices, hosted by Sen. Bill Bradley (also appearing under the title American Voices with Senator Bill Bradley), produced by Devorah Klahr for Sirius XM Satellite Radio, Washington, D.C. Dyann Arthur and Rick Arthur Collection of MusicBox Project Materials (AFC 2010/029) Over 100 hours of audio and video interviews of women working as roots musicians and/or singers. -

Wavelength (January 1985)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 1-1985 Wavelength (January 1985) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (January 1985) 51 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/51 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEW ORLEANS MUSIC MAGAZ, " ISSUE NO. 51 JANUARY • 1985 $1.50 S . s DrPT. IULK RATE US POSTAGE JAH ' · 5 PAID Hew Orleans. LA EARL K.LC~G Perm1t No. 532 UBRf\RYu C0550 EARL K LONG LIBRARY UNIV OF N. O. ACQUISITIONS DEPT N. O. I HNNY T L)e GO 1ST B T GOSP RO P E .NIE • THE C T ES • T 0 S & T ALTER MOUTON, , 0 T & BOUR E (C JU S) • OBER " UNI " 0 KWO • E ·Y AY • PLEASA T JOSE H AL BL ES N GHT) 1 Music Pfogramming M A ~ -----leans, 2120 Canal, New Orleans, LA-70112 WAVELENGTH ISSUE NO. 51 e JANUARY 1985 "I'm not sure, but I'm almost positive, that all music came from New Orleans." Ernie K-Doe, 1979 FEATURES Remembering the Beaconette ...... 14 The Line ........................ 22 An American Mother . ............. 24 1984 Band Guide ................. 27 DEPARTMENTS January News .................. ... 4 It's Music . 8 Radio ........................... 14 New Bands ...................... 13 Rhythmics. 10 January Listings . ................. 3 3 C/assijieds ...................... -

Suspension and Light: the Films of V~Ctor Erice

SUSPENSION AND LIGHT: THE FILMS OF V~CTORERICE Dominique Russell A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Graduate Department of Spanish and Portuguese 0 Copyright by Dominique Russell 1998 The author has granted a non- L'auteur a sccorde me licence non exclusive licence dowing the exclusive permettant a la National Lrirary of Canada to Bibliothkque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduke, preter' distniiuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de microfiche/£h, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format electronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur consewe la propriete du copyright in this thesis. Neither the clroit d'auteur qui protkge cette these. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes reproduced without the author's ou autrement repmduits sans son permission. autorisation. Thesis Abstract Suspension and Light: The Films of Victor Erie Ph-DI 1998 Dominique Russell Department of Spanish and Portuguese University of Toronto This thesis is a st~~dyof Victor Erice's cinematic style through a close analysis of his three feature films: El espiiinc de la cohena [lk Spmt ofthe Beehive] ( 1973),El SM South] ( 1982) and El sol dei membrillo [The Quince Tree Sun] ( 1992). It examines stylistic choices made in editing, sound, mise en dne,camera movement and structure, focusing on the elements which contribute to the ambiguous and meditative quality of Erice's films.