Meteorological Glossary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Air Masses and Fronts

CHAPTER 4 AIR MASSES AND FRONTS Temperature, in the form of heating and cooling, contrasts and produces a homogeneous mass of air. The plays a key roll in our atmosphere’s circulation. energy supplied to Earth’s surface from the Sun is Heating and cooling is also the key in the formation of distributed to the air mass by convection, radiation, and various air masses. These air masses, because of conduction. temperature contrast, ultimately result in the formation Another condition necessary for air mass formation of frontal systems. The air masses and frontal systems, is equilibrium between ground and air. This is however, could not move significantly without the established by a combination of the following interplay of low-pressure systems (cyclones). processes: (1) turbulent-convective transport of heat Some regions of Earth have weak pressure upward into the higher levels of the air; (2) cooling of gradients at times that allow for little air movement. air by radiation loss of heat; and (3) transport of heat by Therefore, the air lying over these regions eventually evaporation and condensation processes. takes on the certain characteristics of temperature and The fastest and most effective process involved in moisture normal to that region. Ultimately, air masses establishing equilibrium is the turbulent-convective with these specific characteristics (warm, cold, moist, transport of heat upwards. The slowest and least or dry) develop. Because of the existence of cyclones effective process is radiation. and other factors aloft, these air masses are eventually subject to some movement that forces them together. During radiation and turbulent-convective When these air masses are forced together, fronts processes, evaporation and condensation contribute in develop between them. -

Postal Bulletin 22137 (9-16-04)

NATIONAL STAMP COLLECTING MONTH PUBLICITY KIT, PAGE 9 PUBLISHED SINCE MARCH 4, 1880 PB 22137, September 16, 2004 2 POSTAL BULLETIN 22137 (9-16-04) CONTENTS The Postal Bulletin is also available on the World Wide Finance Web at http://www.usps.com/cpim/ftp/bulletin/pb.htm for Notice: Household Diary Study. 81 customers and at http://blue.usps.gov for employees. International Mail ICM Updates: International Customized Mail. 82 USPSNEWS@WORK . 3 Licensing Administrative Services Promotions. 86 Directives and Forms Update. 5 Philately Customer Relations Stamp Announcement 04-31: Christmas: Madonna and Mail Alert. 7 Child by Lorenzo Monaco Stamp. 88 Publicity Kit: National Stamp Collecting Month. 9 Stamp Announcement 04-32: Hanukkah Stamp. 90 Stamp Announcement 04-33: Kwanzaa Stamp. 92 Domestic Mail The Postal Service Guide to U.S. Stamps, 31st DMM Revision: Labeling List Changes. 36 Edition. 94 DMM Revision: Periodicals Combined Mailing. 38 Pictorial Cancellations Announcement. 96 DMM Revision: Realignment of ZIP Codes: Destination Special Cancellation Die Hubs. 104 Entry and BMC Service Areas. 39 DMM Revision: Periodicals Irregular Parcels. 40 Post Offices New Form: PS Form 3811-I, Instructions for Requesting Post Office Changes. 106 Return Receipt (Electronic) . 41 Mover’s Guide News: September 2004 Mover’s Guide Fall Mailing Season. 42 Now Available. 108 Field Information Kit: Return Receipt (Electronic). 43 Deliver It Right. 109 Retail ReadyPost Sales Contest: Everyone Sells, Everyone Pull-Out Section Wins!. 110 Fraud Alert Postal Bulletin Index Withholding of Mail Orders. 45 Semiannual Index. PB 22132 (7-8-04) Invalid Express Mail Corporate Account Numbers. 46 Missing, Lost, or Stolen U.S. -

Hadley's Principle: Understanding and Misunderstanding the Trade

History of Meteorology 3 (2006) 17 Hadley’s Principle: Understanding and Misunderstanding the Trade Winds Anders O. Persson Department for research and development Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute SE 601 71 Norrköping, Sweden [email protected] Old knowledge will often be rediscovered and presented under new labels, causing much confusion and impeding progress—Tor Bergeron.1 Introduction In May 1735 a fairly unknown Englishman, George Hadley, published a groundbreaking paper, “On the Cause of the General Trade Winds,” in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. His path to fame was long and it took 100 years to have his ideas accepted by the scientific community. But today there is a “Hadley Crater” on the moon, the convectively overturning in the tropics is called “The Hadley Cell,” and the climatological centre of the UK Meteorological Office “The Hadley Centre.” By profession a lawyer, born in London, George Hadley (1685-1768) had in 1735 just became a member of the Royal Society. He was in charge of the Society’s meteorological work which consisted of providing instruments to foreign correspondents and of supervising, collecting and scrutinizing the continental network of meteorological observations2. This made him think about the variations in time and geographical location of the surface pressure and its relation to the winds3. Already in a paper, possibly written before 1735, Hadley carried out an interesting and far-sighted discussion on the winds, which he found “of so uncertain and variable nature”: Hadley’s Principle 18 …concerning the Cause of the Trade-Winds, that for the same Cause the Motion of the Air will not be naturally in a great Circle, for any great Space upon the surface of the Earth anywhere, unless in the Equator itself, but in some other Line, and, in general, all Winds, as they come nearer the Equator will become more easterly, and as they recede from it, more and more westerly, unless some other Cause intervene4. -

Geography P1 November 2019 Marking Guidelines

NATIONAL SENIOR CERTIFICATE GRADE 12 GEOGRAPHY P1 NOVEMBER 2019 MARKING GUIDELINES MARKS: 225 These marking guidelines consist of 26 pages. Copyright reserved Please turn over Geography/P1 2 DBE/November 2019 NSC – Marking Guidelines Marking Guidelines The following marking guidelines have been developed to standardise marking in all provinces. Marking • ALL selected questions MUST be marked, irrespective of whether it is correct or incorrect • Candidates are expected to make a choice of THREE questions to answer. If all questions are answered, ONLY the first three questions are marked. • A clear, neat tick must be used: o If ONE mark is allocated, ONE tick must be used: o If TWO marks are allocated, TWO ticks must be used: o The tick must be placed at the FACT that a mark is being allocated for o Ticks must be kept SMALL, as various layers of moderation may take place • Incorrect answers must be marked with a clear, neat cross: o Use MORE than one cross across a paragraph/discussion style questions to indicate that all facts have been considered o Do NOT draw a line through an incorrect answer o Do NOT underline the incorrect facts • Where the maximum marks have been allocated in the first few sentences of a paragraph, place an M over the remainder of the text to indicate the maximum marks have been achieved For the following action words, ONE word answers are acceptable: give, list, name, state, identify For the following action words, a FULL sentence must be written: describe, explain, evaluate, analyse, suggest, differentiate, -

Study & Master Geography Grade 12 Teacher's Guide

Ge0graphy CAPS Grade Teacher’s Guide Helen Collett • Norma Catherine Winearls Peter J Holmes 12 SM_Geography_12_TG_CAPS_ENG.indd 1 2013/06/11 6:21 PM Study & Master Geography Grade 12 Teacher’s Guide Helen Collett • Norma Catherine Winearls • Peter J Holmes SM_Geography_12_TG_TP_CAPS_ENGGeog Gr 12 TG.indb 1 BW.indd 1 2013/06/116/11/13 7:13:30 6:09 PMPM CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Mexico City Cambridge University Press The Water Club, Beach Road, Granger Bay, Cape Town 8005, South Africa www.cup.co.za © Cambridge University Press 2013 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2013 ISBN 978-1-107-38162-9 Editor: Barbara Hutton Proofreader: Anthea Johnstone Artists: Sue Abraham and Peter Holmes Typesetter: Brink Publishing & Design Cover image: Gallo Images/Wolfgang Poelzer/Getty Images ………………………………………………......…………………………………………………………… ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Photographs: Peter Holmes: pp. 267, 271, 273 and 274 Maps: Chief Directorate: National Geo-spatial Information: Department of Rural Development and Land Reform: pp. 189, 233–235 and 284–289 ………………………………………………......…………………………………………………………… Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Information regarding prices, travel timetables and other factual information given in this work are correct at the time of first printing but Cambridge University Press does not guarantee the accuracy of such information thereafter. -

NATURE June 9, 1945, Vol

688 NATURE jUNE 9, 1945, VoL. 155 fashioned, they may be regarded as essays in the the incongruity between them and the castle and harmony of orange and red, and the employment of cathedral in the background is so violent as almos1 suitable contrasts and discords. So far as one may to be bad manners and not merely bad art ; if, or judge from the background of "Reclining Figure" the other hand, they are mere symbols to indicatt (No. 678), the artist himself would prefer the latter where new building will be necessary, one must theory. defer judgment until the designs for the actual Purple in its lighter tones has ruined many acres buildings have been produced. The other doubtful of canvas in pictures of the 'sheep-among-the-heather' case is Sir Giles Gilbert Scott's design for the new type, but in its deeper tones it is rich and magnificent, Coventry Cathedral, of which the interior does not though still dangerous. The State portraits by strike one as suitable for an ecclesiastical building, Gerald Kelly (Gallery III) are noteworthy for the neither does it appear to be in keeping with the skill with which the imperial purple is rendered, a exterior. skill which cannot be fully appreciated without the Taking the exhibition as a whole, it is lively, realization that instead of the usual foils of green varied, and of good quality. To expect it to indicate and brown these great masses of colour are displayed a definite trend in any particular direction, or in in a setting of parian coolness, and yet never for one favour of any one school, is unreasonable, since tc stroke of the brush does the colour get out of control. -

An Access-Dictionary of Internationalist High Tech Latinate English

An Access-Dictionary of Internationalist High Tech Latinate English Excerpted from Word Power, Public Speaking Confidence, and Dictionary-Based Learning, Copyright © 2007 by Robert Oliphant, columnist, Education News Author of The Latin-Old English Glossary in British Museum MS 3376 (Mouton, 1966) and A Piano for Mrs. Cimino (Prentice Hall, 1980) INTRODUCTION Strictly speaking, this is simply a list of technical terms: 30,680 of them presented in an alphabetical sequence of 52 professional subject fields ranging from Aeronautics to Zoology. Practically considered, though, every item on the list can be quickly accessed in the Random House Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary (RHU), updated second edition of 2007, or in its CD – ROM WordGenius® version. So what’s here is actually an in-depth learning tool for mastering the basic vocabularies of what today can fairly be called American-Pronunciation Internationalist High Tech Latinate English. Dictionary authority. This list, by virtue of its dictionary link, has far more authority than a conventional professional-subject glossary, even the one offered online by the University of Maryland Medical Center. American dictionaries, after all, have always assigned their technical terms to professional experts in specific fields, identified those experts in print, and in effect held them responsible for the accuracy and comprehensiveness of each entry. Even more important, the entries themselves offer learners a complete sketch of each target word (headword). Memorization. For professionals, memorization is a basic career requirement. Any physician will tell you how much of it is called for in medical school and how hard it is, thanks to thousands of strange, exotic shapes like <myocardium> that have to be taken apart in the mind and reassembled like pieces of an unpronounceable jigsaw puzzle. -

Remember the Met Office in World War One and World War Two

Remember The Met Office in World War One and World War Two National Meteorological Library and Archive The National Meteorological Library and Archive Many people have an interest in the weather and the processes that cause it and the National Meteorological Library and Archive is a treasure trove of meteorological and related information. We are open to everyone. The Library and Archive are vital for maintaining the public memory of the weather, storing meteorological records and facilitating learning. Our collections We hold a world class collection on meteorology which includes a comprehensive library of published books, journals and reports as well as a unique archive of original meteorological data, weather charts, private weather diaries and much more. These records provide access to historical data and give a snapshot of life and the weather both before and after the establishment of the Met Office in 1854 when official records began. Online catalogue Details of all our holdings are catalogued and access to this is available across the internet just go to www.library.metoffice.gov.uk. From here you will also be able to directly access any of our electronic content. The Meteorological Office in World War One The Meteorological Office in World War One At the start of the war little significance was attached to the importance of meteorology in warfare; a pilot would simply look out of the window to assess whether conditions were suitable for flying and hope that they remained so. Following losses in the air and on the ground, and the deployment of gas as a weapon on the battlefield, attitudes changed rapidly. -

Biographical Sketches of Leading Meteorologists and Scientists of the Period from 1830 to 1920

Appendix Biographical Sketches of Leading Meteorologists and Scientists of the Period from 1830 to 1920 The scientists listed in this Appendix made important contributions to Nine teenth and early Twentieth Century meteorology and, in particular, to the develop ment of the thermal theory of cyclones .1 Their work forms the focus of this study. The brief sketches are intended to provide in a condensed form information about important steps in the professional careers of the scientists listed, and some indication of their major contributions to science. Information on aspects of the personal lives of these scientists has been included only sparingly. In many cases I found the source material very meager, especially with regard to personal informa tion; this is reflected in the brevity of a great number of the entries. The bibliographical references at the end of each sketch consist primarily of obituaries and contemporary memoirs. Modem biographies and memoirs have been listed whenever available. JOHANN FRIEDRICH WILHELM VON BEZOLD (1837 -1907) was born in Miinchen, Germany, the son of a high government official. He studied physics in Miinchen and Gottingen (under W. Weber and B. Riemann). After receiving his doctorate in 1860 he was appointed assistant to the physicist von Jolly in Miinchen. In 1861 he became privatdocent, and he was named extraordinary professor of physics 1 J. Bjerknes and H.' Solberg, who in 1920 stood just at the beginning of their careers, have not been included in this list. Accounts of J. Bjerknes' professional career may be found in J. A. B. Bjerknes, Selected Papers (Western Periodicals Company, 1975), pp. -

Magazine Issue 29 2015 Australian Antarctic Magazine Issue 29 2015

AUSTRALIAN ANTARCTIC MAGAZINE ISSUE 29 2015 AUSTRALIAN ANTARCTIC MAGAZINE ISSUE 29 2015 The Australian Antarctic Division, a Division of the Department of the Environment, leads Australia’s Antarctic program and seeks to advance Australia’s Antarctic interests in pursuit of its vision of having ‘Antarctica valued, protected and understood’. It does this by managing Australian government activity in Antarctica, providing transport and logistic support to Australia’s Antarctic research program, maintaining four permanent Australian research stations, and conducting scientific research SCIENCE programs both on land and in the Southern Ocean. 12 Measuring algae in the fast ice Australia’s Antarctic national interests are to: • Preserve our sovereignty over the Australian Antarctic ICEBREAKER HISTORY Territory, including our sovereign rights over the 16 New icebreaker plans unveiled 24 Two-wheeled Antarctic adventures adjacent offshore areas. • Take advantage of the special opportunities Antarctica offers for scientific research. • Protect the Antarctic environment, having regard to its special qualities and effects on our region. • Maintain Antarctica’s freedom from strategic and/or political confrontation. • Be informed about and able to influence developments in a region geographically proximate to Australia. • Derive any reasonable economic benefits from living and non-living resources of the Antarctic (excluding deriving such benefits from mining and oil drilling). Australian Antarctic Magazine seeks to inform the Australian and international Antarctic community about the activities of the Australian Antarctic program. Opinions expressed in Australian Antarctic Magazine do not necessarily represent the position of the Australian CONTENTS Government. Australian Antarctic Magazine is produced twice a year DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE POLICY (June and December). All text and images published in the Australia’s Antarctic future 1 Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting 19 magazine are copyright of the Commonwealth of Australia, unless otherwise stated. -

SANGO 2019 Memo

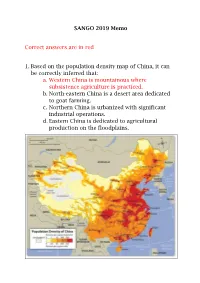

SANGO 2019 Memo Correct answers are in red 1. Based on the population density map of China, it can be correctly inferred that: a. Western China is mountainous where subsistence agriculture is practiced. b. North-eastern China is a desert area dedicated to goat farming. c. Northern China is urbanized with significant industrial operations. d. Eastern China is dedicated to agricultural production on the floodplains. 2. Which of the four stages in the demographic transition model are considered “homeostatic” stages, that is, when the forces of demographic change are in equilibrium? a. Stages 1 and 3. b. Stage 3 and 4. c. Stages 2 and 3. d. Stages 1 and 4. 3. Which of the following strategies was identified by the 2004 United Nations International Conference on Population and Development as the most powerful approach for reducing the global population growth rate? a. Removing anti-contraception laws in conservative countries. b. Reducing vaccination rates. c. Empowering women in less-developed countries. d. Enforcing demographic growth rate targets. 4. At the centre of this relief map is the country of Iran. What type of landscape feature dominates the Iranian landscape? a. Floodplain. b. Plateau. c. Rift valley. d. Mesa. 5. The islands of the Pacific are home to some of the world’s first climate change refugees. This is primarily because of: a. Floods destroying agriculture. b. Tropical cyclones destroying infrastructure. c. Rising sea levels inundating habitable areas. d. Increasing ocean salinity causing fish die off. 6. The correct labels for the numbers 3, 6, 12, and 13 in this cross-section of a volcano are, in order: a. -

World Weather Watch Information on The

WORLD METEOROLOGICAL ORGANIZATION WORLD WEATHER WATCH GLOBAL OBSERVING SYSTEM - SATELLITE SUB-SYSTEM INFORMATION ON THE APPLICATION OF METEOROLOGICAL SATELLITE DATA IN ROUTINE OPERATIONS AND RESEARCH ABSTRACTS, ANNUAL SUMMARIES AND BIBLIOGRAPHIES Supplement No. 2 (Papers and Publications issued in 1977) I WMO ·No. 475 I Secretariat of the World Meteorological Organization • Geneva • Switzerland CONTENTS Contributions from Australia Bulgaria Canada German Democratic Republic Germany, Federal Republic of Hungary India Israel Japan Poland Switzerland United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland Union of Soviet Socialist Republics United States of America AUSTRALIA 1 1. Title of the paper On the direction of mot~on Tropical Cyclone Tracy 2. Name of publication Bureau of Meteorology, Technical Report Series 3. Language in which the paper is available English 4. Author F~A. Lajoie 5. Affiliation : Bureau of Meteorology, Australia 6. Abstract ~ According to the guidelines of Lajoie and Nicholls (1974) for forecasting the direction of mo·Gion of tropical cyclones from satellite cloud pictures, a cyclone will move within 12 hours of picture time, in a direction paral lel to a line joining the position of the vortex centre and that of the most developed cumulonimbus cluster at or near the downstream end of the outer cloudba:nd. These guidelines imply that a time interval exists betvreen the formation of the outer cloudband and the moment the cyclone changes its direction of motion. There has always been some doubt about the veracity of this particular aspect of the guidelines beeause of the possibility that the best-determined positions of cyclone centres, and hence of the cyclone tracks, used in the previous investigation were not sufficiently accurate in time and space.