Biological Impacts Mangrooves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pulih Sepenuhnya Pada 8:00 Pagi, 21 Oktober 2020 Kumpulan 2

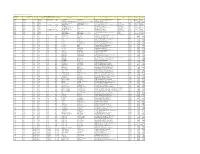

LAMPIRAN A SENARAI KAWASAN MENGIKUT JADUAL PELAN PEMULIHAN BEKALAN AIR DI WILAYAH PETALING, GOMBAK, KLANG/SHAH ALAM, KUALA LUMPUR, HULU SELANGOR, KUALA LANGAT DAN KUALA SELANGOR 19 OKTOBER 2020 WILAYAH : PETALING ANGGARAN PEMULIHAN KAWASAN Kumpulan 1: Kumpulan 2: Kumpulan 3: Pulih Pulih Pulih BIL. KAWASAN sepenuhnya sepenuhnya sepenuhnya pada pada pada 8:00 pagi, 8:00 pagi, 8:00 pagi, 21 Oktober 2020 22 Oktober 2020 23 Oktober 2020 1 Aman Putri U17 / 2 Aman Suria / 3 Angkasapuri / 4 Bandar Baru Sg Buloh Fasa 3 / 5 Bandar Baru Sg. Buloh Fasa 1&2 / 6 Bandar Baru Sri Petaling / 7 Bandar Kinrara / 8 Bandar Pinggiran Subang U5 / 9 Bandar Puchong Jaya / 10 Bandar Tasek Selatan / 11 Bandar Utama / 12 Bangsar South / 13 Bukit Indah Utama / 14 Bukit Jalil / 15 Bukit Jalil Resort / 16 Bukit Lagong / 17 Bukit OUG / 18 Bukit Rahman Putra / 19 Bukit Saujana / 20 Damansara Damai (PJU10/1) / 21 Damansara Idaman / 22 Damansara Lagenda / 23 Damansara Perdana (Raflessia Residency) / 24 Denai Alam / 25 Desa Bukit Indah / 26 Desa Moccis / 27 Desa Petaling / 28 Eastin Hotel / 29 Elmina / 30 Gasing Indah / 31 Glenmarie / 32 Hentian Rehat dan Rawat PLUS (R&R) / 33 Hicom Glenmarie / LAMPIRAN A SENARAI KAWASAN MENGIKUT JADUAL PELAN PEMULIHAN BEKALAN AIR DI WILAYAH PETALING, GOMBAK, KLANG/SHAH ALAM, KUALA LUMPUR, HULU SELANGOR, KUALA LANGAT DAN KUALA SELANGOR 19 OKTOBER 2020 WILAYAH : PETALING ANGGARAN PEMULIHAN KAWASAN Kumpulan 1: Kumpulan 2: Kumpulan 3: Pulih Pulih Pulih BIL. KAWASAN sepenuhnya sepenuhnya sepenuhnya pada pada pada 8:00 pagi, 8:00 pagi, 8:00 -

Malaysia Port Klang Power Station Project (Phase 3 /Phase 3-Stage2)

Malaysia Port Klang Power Station Project (Phase 3 /Phase 3-Stage2) External Evaluator: Taro Tsubogo (KRI International Corp.) Tenaga Nasional Berhad1 Field Survey: March, 2006 1. Project Profile and Japan’s ODA Loan Location of the project site Port Klang (Kapar Phase 3) power station 1.1 Background With the high economic growth, energy demand in the Peninsular Malaysia had grown significantly over the last years with an annual growth rate of 11.4% to 3,447 MW in 1990. Although the growth pace was expected to slow down in the future, energy demand was forecasted to reach 10,448 MW in 2000 with an annual growth rate of 10.6%. Since total installed capacity in 1990 was still 4,576 MW, a serious energy shortage was expected to occur in the future. To fill this gap, construction and expansion of power plants was indispensable option. On the other hand, the Malaysian Government carried out “Four fuel diversification strategy” to enhance the use of indigenous resources and reduce petroleum dependency. The Sixth Malaysia Plan (1991-1995) also envisioned to augment gas supply. The project, to construct 1,000 MW multi-fuel fired power plant, was therefore expected to contribute to both increment of supply capacity and diversification of energy source. 1.2 Objectives The project’s objective was to meet the rapidly increasing demand for energy and assure stable energy supply in the Peninsular Malaysia through construction of a thermal power station (known as Kapar Phase 3 Plant) located adjacent to the existing plants in Port Klang area, and thereby contribute to further economic growth and reducing oil dependence of the country. -

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills As of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills as of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct Supplier Second Refiner First Refinery/Aggregator Information Load Port/ Refinery/Aggregator Address Province/ Direct Supplier Supplier Parent Company Refinery/Aggregator Name Mill Company Name Mill Name Country Latitude Longitude Location Location State AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora Agroaceite Extractora Agroaceite Finca Pensilvania Aldea Los Encuentros, Coatepeque Quetzaltenango. Coatepeque Guatemala 14°33'19.1"N 92°00'20.3"W AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora del Atlantico Guatemala Extractora del Atlantico Extractora del Atlantico km276.5, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Champona, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°35'29.70"N 88°32'40.70"O AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora La Francia Extractora La Francia km. 243, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Buena Vista, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°28'48.42"N 88°48'6.45" O Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - ASOCIACION AGROINDUSTRIAL DE PALMICULTORES DE SABA C.V.Asociacion (ASAPALSA) Agroindustrial de Palmicutores de Saba (ASAPALSA) ALDEA DE ORICA, SABA, COLON Colon HONDURAS 15.54505 -86.180154 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - Cooperativa Agroindustrial de Productores de Palma AceiteraCoopeagropal R.L. (Coopeagropal El Robel R.L.) EL ROBLE, LAUREL, CORREDORES, PUNTARENAS, COSTA RICA Puntarenas Costa Rica 8.4358333 -82.94469444 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - CORPORACIÓN -

List of Installations Affected Under Efficient Management of Electrical Energy Regulations 2008 (Emeer 2008) State: Selangor

LIST OF INSTALLATIONS AFFECTED UNDER EFFICIENT MANAGEMENT OF ELECTRICAL ENERGY REGULATIONS 2008 (EMEER 2008) STATE: SELANGOR No. Installation Name Address 12 (10 & 8),JLN TLK GADUNG 27/93,40400 SEKSYEN 27,SHAH ALAM, 1 PERUSAHAAN JAYA PLASTIK SELANGOR 2 PLASTIC CENTRE SDN BHD 6065,JLN HJ ABD MANAN BT 5,,41050 MERU,KLANG, SELANGOR LOT 1, JALAN P/2A, KAWASAN PERUSAHAAN PKT 1, 43650 BANDAR BARU 3 PLASTICTECNIC (M) SDN BHD BANGI, SELANGOR LOT 8595, KG. AIR HITAM, BATU 6 1/2, JALAN LANGAT, 41200 KLANG, 4 PLASTIK V SDN BHD SELANGOR LOT 60 & 61, JALAN SUNGAI PINANG 5/1, SEKSYEN 5, FASA 2A, TAMAN 5 POSCO-MALAYSIA SDN BHD PERINDUSTRIAN PULAU INDAH, 42920 PELABUHAN KLANG, SELANGOR 6464 & 6486,JLN SG PULUH,42100 KAW PERINDUSTRIAN LADANG SG 6 PRESS METAL BERHAD PULUH,KAPAR, SELANGOR 24,JLN CJ 1,43200 BERSATU INDUSTRIAL PARK CHERAS 7 R O WATER SDN BHD JAYA,BALAKONG, SELANGOR 11,JLN PERUSAHAAN 1,43700 BERANANG IND ESTATE,BERANANG, 8 RANK METAL SDN BHD SELANGOR NO. 2,JLN SULTAN MOHAMED 1, ,42000 KAWASAN PERINDUSTRIAN 9 KAWAGUCHI MFG. SDN BHD BANDAR SULTAN SULAIMAN,PELABUHAN KLANG, SELANGOR 10 BOX-PAK (MALAYSIA) BHD LOT 4 JALAN PERUSAHAAN 2, 68100 BATU CAVES, SELANGOR Inti Johan Sdn. Bhd., Lot. 18, Level 3 (1 St Floor), Persiaran Mpaj, Jalan Pandan 11 PANDAN KAPITAL Utama, Pandan Indah, 55100 Kuala Lumpur LOT 1888,JLN KPB 7,43300 KAWASAN PERINDUSTRIAN BALAKONG,SERI 12 MEGAPOWER HOLDINGS S/BHD KEMBANGAN, SELANGOR AVERY DENNISON MATERIALS SDN LOT 6 JALAN P/2, KAWASAN PERUSAHAAN BANGI, 43650 BANGI 13 BHD SELANGOR NO. -

Senarai Kerja Undi 1/2021 Pejabat Daerah / Tanah Klang

LAMPIRAN A SENARAI KERJA UNDI 1/2021 PEJABAT DAERAH / TANAH KLANG Semua Kontraktor Bumiputra Kelas F / G1 yang berdaftar dengan Pusat Khidmat Kontraktor (PKK) & Lembaga Pembangunan Industri Pembinaan Malaysia (CIDB) serta Unit Perancang Ekonomi Negeri Selangor (UPEN) beralamat di DAERAH KLANG adalah dijemput untuk menyertai undian bagi Perolehan Kerja - Kerja Kecil Bahagian Pembangunan, Pejabat Daerah/Tanah Klang seperti berikut :- BIL TAJUK PROJEK SYARAT HARGA PENDAFTARAN PROJEK (RM) 1. KERJA-KERJA MEMBAIKPULIH DAN GRED ‘G1’ MENYELENGGARA JALAN MASUK KE KATEGORI CE TANAH PERKUBURAN ISLAM KG PENGKHUSUSAN 100,000.00 PENDAMAR, PELABUHAN KLANG CE01 DAN CE21 2. KERJA-KERJA MEMBAIKPULIH DAN GRED ‘G1’ MENYELENGGARA PERMUKAAN KATEGORI CE DATARAN KEJAT DI MASJID KAMPUNG PENGKHUSUSAN 70,000.00 PENDAMAR, PELABUHAN KLANG B04 DAN CE21 3. KERJA-KERJA MEMBAIKPULIH DAN GRED ‘G1’ MENYELENGGARA BALAI MPKK KG KATEGORI CE 100,000.00 PANDAMARAN JAYA, PELABUHAN KLANG PENGKHUSUSAN B04 DAN CE21 4. KERJA-KERJA MEMBAIKPULIH DAN GRED ‘G1’ MENYELENGGARA BUMBUNG DI KATEGORI CE 20,000.00 PENGKALAN NELAYAN KG KAPAR PENGKHUSUSAN B04 DAN CE21 5. KERJA-KERJA MEMBAIKPULIH DAN GRED ‘G1’ MENYELENGGARA GELANGGANG KATEGORI CE 50,000.00 FUTSAL DI KG. KAPAR PENGKHUSUSAN CE21 1 6. KERJA-KERJA MEMBAIKPULIH DAN GRED ‘G1’ MENYELENGGARA SURAU HJ WAHIDON KATEGORI CE 50,000.00 KG SEMENTA PENGKHUSUSAN B04 DAN CE21 7. KERJA-KERJA MEMBAIKPULIH DAN GRED ‘G1’ MENYELENGGARA DEWAN ORANG KATEGORI CE 100,000.00 RAMAI KG PEREPAT PENGKHUSUSAN B04 DAN CE21 8. KERJA-KERJA MEMBAIKPULIH TEMBOK GRED ‘G1’ DAN PAGAR DI BALAI MPKK DAN DEWAN KATEGORI CE 25,000.00 KG PADANG JAWA, KLANG PENGKHUSUSAN CE21 9. KERJA-KERJA MENAIKTARAF GRED ‘G1’ LONGKANG DAN MENAIKTARAF JALAN KATEGORI CE SERTA PEMBERSIHAN LONGKANG DI PENGKHUSUSAN 100,000.00 LORONG HAJI SALLEH, KG KUANTAN, CE01 DAN CE21 KLANG 10. -

Intercontinental Specialty Fats Sdn. Bhd

Intercontinental Specialty Fats Sdn Bhd Traceability Assessment Period: July - September 2020 Crude Palm Oil (CPO) Suppliers RSPO MSPO SG PO No. Palm Oil Mill UML Parent Company of (P.O.M) Address State Latitude Longtitude Certification Certification Delivered 92 KM Off Kuantan-Segamat Highway, 26700 1 Dara Lam Soon PO1000007798 Lam Soon Plantations Sdn Bhd Pahang 3.15702 103.16363 Yes Yes X Muadzam Shah, Pahang, Malaysia KM 12, Jalan Jelai - Rompin, 72100 Bahau, Negeri 2 Jeram Padang PO1000000280 Kuala Lumpur Kepong Berhad Negeri Sembilan 2.7351111 102.4085 Yes Yes X Sembilan, Malaysia 3 KKS Changkat Chermin PO1000000896 Kuala Lumpur Kepong Berhad Batu 13 1/2, 32400 Ayer Tawar, Perak, Malaysia Perak 4.27527 100.78498 Yes Yes X 4 KKS Batu Lintang PO1000000894 Kuala Lumpur Kepong Berhad 09800 Serdang, Kedah, Malaysia Kedah 5.1936111 100.6286111 Yes Yes X 5 Tereh PO1000001263 Kulim Berhad K.B 538, 86009 Kluang, Johor, Malaysia Johor 2.217518 103.35139 Yes Yes X 6 Pasir Panjang PO1000005256 Kulim Berhad K.B 527, 81909 Kota Tinggi, Johor, Malaysia Johor 2.01801 103.94858 Yes Yes X 7 Palong Cocoa PO1000001265 Kulim Berhad K.B 504, 85009 Segamat, Johor, Malaysia Johor 2.7064 102.78501 Yes Yes X Off KM 40, Jalan Jeroco, 91109 Lahad Datu, Sabah, 8 Jeroco 1 PO1000000936 Hap Seng Plantations Holdings Berhard Sabah 5.3373003 118.417222 Yes Yes X Malaysia Off KM 40, Jalan Jeroco, 91109 Lahad Datu, Sabah, 9 Bukit Mas PO1000000185 Hap Seng Plantations Holdings Berhard Sabah 5.3373003 118.47364 Yes Yes X Malaysia 250, Jln. -

Malaysian Minerals Yearbook 2010

MALAYSIAN MINERALS YEARBOOK 2010 MINERALS AND GEOSCIENCE DEPARTMENT MALAYSIA MINISTRY OF NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENT MALAYSIA Twentieth Issue Price: RM70.00 Kilometres PREFACE Each year, the Minerals and Geoscience Department Malaysia (JMG) undertakes a comprehensive compilation and review of the development in the country's mineral industry and publishes the results as the Malaysian Minerals Yearbook (MMYB). Its aim is to provide reliable and comprehensive information on the entire minerals produced in Malaysia. This issue is the 20th edition of MMYB, and as in the previous editions the main focus of the publication is the metallic, non-metallic mineral and coal. In addition, it provides information on production and trade which will serve as a useful reference text for the mineral industry. This MMYB incorporates chapters devoted to each mineral commodity produced in Malaysia. Amongst the information included are commodity reviews, minerals production, import, export, prices and analyses of the mineral commodities. Starting from this issue of MMYB the section on exploration and mining activities were no longer be reported but will be incorporated in another department's publication i.e. Malaysian Mining Industry report. However, a new chapter on manganese is included to give a full review due to the increase activities for this commodity. The Minerals and Geoscience Department continuously strives to improve the quality of its publications for the benefit of the mineral fraternity. We welcome any constructive comments and suggestions by readers that may help us to meet the changing needs and requirements of the mineral sector. Finally, I would like to extend my sincere appreciation to government agencies, various organisations, companies and individuals who have been continuously providing valuable information for the preparation of this report and looks forward to similar cooperation and assistance in the future. -

Senarai Semua Lokasi Hotspot Wifi Smart Selangor Adalah Seperti Berikut

Senarai semua lokasi hotspot WiFi Smart Selangor adalah seperti berikut:- No. Site Address Category 1 Masjid Nurul Yaqin Mosque Kampung Melayu Seri Kundang, 48050 Rawang, Selangor 2 Pusat Gerakan Khidmat Masyarakat (DUN Kuang) Government 6-1-A, Jalan 7A/2, Bandar Tasik Puteri, 48000 Rawang, Selangor 3 HOSPITAL SUNGAI BULOH_300014, 47000 Hospital Sungai Buloh Selangor 4 HOSPITAL SUNGAI BULOH_300014 Hospital 5 HOSPITAL SUNGAI BULOH_300014 Hospital 6 HOSPITAL SUNGAI BULOH_300014 Hospital 7 HOSPITAL SUNGAI BULOH_300014 Hospital 8 HOSPITAL SUNGAI BULOH_300014 Hospital 9 Perodua Service Centre Jln Sungai Pintas, No.14, Commercial Jalan TSB 10, Taman Industri Sg. Buloh 47000 Shah Alam selangor 10 TESCO RAWANG_300026, No.1, Jalan Rawang Mall 48000 Rawang Selangor 11 TM POINT RAWANG, TM Premises Lot 21, Jalan Maxwell 48000 Rawang 12 Stadium MPS, Jalan Persiaran 1, Bandar Baru Stadium Selayang, 68100 Batu Caves, Selangor 13 Pejabat Cawangan Rawang, Jalan Bandar Rawang Government 2, Bandar Baru Rawang, 48000 Rawang, Selangor 14 No. 309 Felda Sungai Buaya, 48010 Rawang, Residential Selangor area 15 Traffic Light Chicken Rice Sungai Choh, 48009 F&B outlet Rawang, Selangor 16 Pejabat Khidmat Rakyat (DUN Rawang) Government No.13, Jalan Bersatu 8 (Tingkat Bawah), Taman Bersatu, 48000 Rawang, Selangor 17 WTC Restoran F&B Outlet Rawang new town, 48000 Rawang, Selangor 18 Medan Selera MPS F&B Outlet Rawang Integrated Industrial Park, 45000 Rawang, Taman Tun Teja, Rawang, Selangor 19 Medan Selera F&B Outlet Bandar Country Homes, 48000 Rawang, Selangor 20 Kompleks JKKK, Selayang Baru, JKR 750C, Dewan Government Orang Ramai, Jalan Besar Selayang Baru, 68100 Batu Caves, Selangor 21 Pejabat Ahli Parlimen Selayang,12A, Jalan SJ 17, Government Taman Selayang Jaya, 68100 Batu Caves, Selangor No. -

Sime Darby Property Profile

SIME DARBY PROPERTY BERHAD Citi Asia Pacific Property Conference 2018 Investor Presentation 28 – 29 June 2018 2 Presentation Outline 1 Sime Darby Property Profile Key Growth Areas and Recent 2 Developments 3 Growth Strategies 4 Financial and Operational Highlights 5 Megatrends & Market Outlook 6 Appendices 1 Sime Darby Property 3 4 Shareholding Structure RM1.16 Share Price 55.6% Share Price Movement (RM) 1.78 As at 22 June’18 1.16 1.11 Foreign Shareholdings 14.8% 10.0% RM7.9bn 4.7% Market Capitalisation Other Domestic Shareholdings 14.9% 6,800,839 Number of Ordinary and the public Shares (000’) Source: Tricor 5 The Largest Property Developer in Malaysia In terms of land bank size RM1.7bn RM637mn RM593mn 1,602 9MFY18 Revenue 9MFY18 PBIT 9MFY18 PATAMI Employees UNITED KINGDOM Property Development THAILAND Active townships, integrated and KEDAH 23 niche developments Helensvale, Acres of remaining Queensland developable land bank to be GEORGETOWN, 65 acres 20,695 developed over 10 -25 years PENANG PENINSULA MALAYSIA AUSTRALIA Estimated Remaining Gross RM96bn Development Value (GDV) Average trading discount to 45% Realised Net Asset Value (RNAV) SELANGOR 3,291 acres Property Investment 3,187 acres Sq. ft. of net commercial 2,826 acres NEGERI space in Malaysia and SEMBILAN 1.4mn Singapore 1,462 acres JOHOR Hospitality & Leisure BANDAR UNIVERSITI PAGOH Assets across 4 countries 3,297 acres Key Developments including 2 golf courses (36-hole 6 & 18-hole respectively) and a North-South Expressway Singapore convention center 6 Sustainable Growth With remaining developable land over 10 to 25 years By Remaining By Remaining Gross Developable Land Development Value (GDV) 7.6 1,461 21.0 (9%) (12%) 3,451 (26%) (28%) O 334 N (3%) G 12,265 28.2 RM81.5 O (35%) 2,826 5.5 I (23%) acres 871 billion (7%) N (7%) G 5.3 (6%) 3,322 13.9 (27%) (17%) Legend: 2,036 F (24%) U 3,092 T 8,430 (37%) RM14.4 U acres billion R for Guthrie Corridor only E 3,302 (39%) Notes: 1. -

Terms of Reference for the Proposed Development On

Detailed EIA for the Proposed Expansion 130.55 Acres Sanitary Landfill in Mukim Jeram, District of Kuala Selangor, Selangor Darul Ehsan (Rev.01). CHAPTER 5.0: DESCRIPTION OF THE EXISTING ENVIRONMENT 5.1 Introduction This chapter basically highlights the existing baseline scenario of physical, biological and socio-economical environment of the Project Site and its surrounding areas. The existing environment is documented to form a basis for the assessment of potential impacts (either positive or negative) generated from the proposed development onto the surrounding environment. Conversely any existing conditions that are likely to impact upon the proposed development itself will also be discussed in this DEIA Report. The prevalent environment will be an indicator of the existing nature’s carrying capacity to adapt to the potential impacts generated by the proposed development. The existing physical environment is determined for an impact area which extends for five (5) km radius from the boundary of the Project Site. The assessment is profiled according to site surveys and published secondary data (i.e. maps, reports and structure plans) made available by the relevant government agencies. 5.2 Topography General topography of the Project Site is identified by use of the Topography Map of Klang, Selangor published by Director of National Mapping Malaysia (1990) as depicted in Figure 5.1. The specific topography and landform of the Project Site is identified using the Survey Plan generated by the Licensed Surveyor i.e., Geosystem Services Sdn. Bhd. (refer to Figure 5.2). The proposed project site is located at the western portion of the existing Jeram Landfill. -

E X Is T in G E N V Ir on M E

06 EXISTING ENVIRONMENT Section 6 EXISTING ENVIRONMENT SECTION 6 : EXISTING ENVIRONMENT 6.1 INTRODUCTION This section describes the existing environment along the Project alignment. The alignment is divided into four segments for the purpose of this assessment, namely Kelantan (1 segment) and Selangor (3 segments). 6.2 TOPOGRAPHY The topography along the ECRL Phase 2 is generally flat to undulating in Segment 1, 2B and 2C. Segment 2A is mostly undulating whereby it passes along Empangan Batu, Templer Park and Serendah Forest Reserve. 6.2.1 Segment 1: Kelantan The topography along this segment is flat. The elevation is low, ranging between 5 m to 15 m since it is close to the coast ( Figure 6.2-1). All slopes in this segment are within Class I (0°-15°) ( Figure 6.2-2). 6.2.2 Segment 2: Selangor Segment 2A: Gombak North to Serendah The alignment from Gombak North to Serendah traversing the southern part of Batu Dam, Hulu Gombak Forest Reserve, Templer Forest Reserve and Serendah Forest Reserve is characterized by gentle-to-flat topography to hilly areas. The elevation from Gombak North to Batu Dam ranges from 110 m to 254 m, and from there the elevation ranges from 229 m to 387 m towards Ulu Gombak Forest Reserve. Next, the alignment passes through Templer Forest Reserve with an elevation ranging between 215 m – 386 m. Before passing through Serendah Forest Reserve, the alignment goes through north of Templer Impian near Templer Park at elevation levels of 128 m – 220 m. The terrain where the alignment passes through Serendah Forest Reserve is undulating at an elevation range of 199 m to 633 m. -

Download File

Cooperation Agency Japan International Japan International Cooperation Agency SeDAR Malaysia -Japan About this Publication: This publication was developed by a group of individuals from the International Institute of Disaster Science (IRIDeS) at Tohoku University, Japan; Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM) Kuala Lumpur and Johor Bahru; and the Selangor Disaster Management Unit (SDMU), Selangor State Government, Malaysia with support from the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). The disaster risk identification and analysis case studies were developed by members of the academia from the above-mentioned universities. This publication is not the official voice of any organization and countries. The analysis presented in this publication is of the authors of each case study. Team members: Dr. Takako Izumi (IRIDeS, Tohoku University), Dr. Shohei Matsuura (JICA Expert), Mr. Ahmad Fairuz Mohd Yusof (Selangor Disaster Management Unit), Dr. Khamarrul Azahari Razak (Universiti Teknologi Malaysia Kuala Lumpur), Dr. Shuji Moriguchi (IRIDeS, Tohoku University), Dr. Shuichi Kure (Toyama Prefectural University), Ir. Dr. Mohamad Hidayat Jamal (Universiti Teknologi Malaysia), Dr. Faizah Che Ros (Universiti Teknologi Malaysia Kuala Lumpur), Ms. Eriko Motoyama (KL IRIDeS Office), and Mr. Luqman Md Supar (KL IRIDeS Office). How to refer this publication: Please refer to this publication as follows: Izumi, T., Matsuura, S., Mohd Yusof, A.F., Razak, K.A., Moriguchi, S., Kure, S., Jamal, M.H., Motoyama, E., Supar, L.M. Disaster Risk Report by IRIDeS, Japan; Universiti Teknologi Malaysia; Selangor Disaster Management Unit, Selangor State Government, Malaysia, 108 pages. August 2019 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 International License www.jppsedar.net.my i Acknowledgement of Contributors The Project Team wishes to thank the contributors to this report, without whose cooperation and spirit of teamwork the publication would not have been possible.