Rural Sanitation in the Tropics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malaysia, September 2006

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Malaysia, September 2006 COUNTRY PROFILE: MALAYSIA September 2006 COUNTRY Formal Name: Malaysia. Short Form: Malaysia. Term for Citizen(s): Malaysian(s). Capital: Since 1999 Putrajaya (25 kilometers south of Kuala Lumpur) Click to Enlarge Image has been the administrative capital and seat of government. Parliament still meets in Kuala Lumpur, but most ministries are located in Putrajaya. Major Cities: Kuala Lumpur is the only city with a population greater than 1 million persons (1,305,792 according to the most recent census in 2000). Other major cities include Johor Bahru (642,944), Ipoh (536,832), and Klang (626,699). Independence: Peninsular Malaysia attained independence as the Federation of Malaya on August 31, 1957. Later, two states on the island of Borneo—Sabah and Sarawak—joined the federation to form Malaysia on September 16, 1963. Public Holidays: Many public holidays are observed only in particular states, and the dates of Hindu and Islamic holidays vary because they are based on lunar calendars. The following holidays are observed nationwide: Hari Raya Haji (Feast of the Sacrifice, movable date); Chinese New Year (movable set of three days in January and February); Muharram (Islamic New Year, movable date); Mouloud (Prophet Muhammad’s Birthday, movable date); Labour Day (May 1); Vesak Day (movable date in May); Official Birthday of His Majesty the Yang di-Pertuan Agong (June 5); National Day (August 31); Deepavali (Diwali, movable set of five days in October and November); Hari Raya Puasa (end of Ramadan, movable date); and Christmas Day (December 25). Flag: Fourteen alternating red and white horizontal stripes of equal width, representing equal membership in the Federation of Malaysia, which is composed of 13 states and the federal government. -

13Th July, 1916

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL. 25 13TH JULY, 1916. PRESENT:― THE COLONIAL TREASURER seconded, and this was agreed to. HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR SIR FRANCIS HENRY MAY, K.C.M.G. THE COLONIAL SECRETARY, by command of H.E. the Governor, laid on the table report of HIS EXCELLENCY MAJOR-GENERAL F. VENTRIS proceedings of Finance Committee, No. 4, and (General Officer Commanding Troops in China). moved that it be adopted. HON. MR. CLAUD SEVERN (Colonial Secretary). THE COLONIAL TREASURER seconded, and this was agreed to. HON. MR. J. H. KEMP (Attorney-General). HON. MR. E. D. C. WOLFE (Colonial Treasurer). Hon. Mr. Pollock and the Government Civil Hospital Nursing Staff HON. MR. E. R. HALLIFAX (Secretary for Chinese Affairs). HON. MR. POLLOCK asked the following HON. MR. W. CHATHAM, C.M.G. (Director of questions:― Public Works). HON. MR. C. MCI. MESSER (Captain (1.)―With reference to the statement, made in Superintendent of Police). answer to my questions concerning the Government Nursing Staff, at the last meeting of the Legislative HON. MR. WEI YUK, C.M.G. Council, to the following effect: "In a further HON. MR. H. E. POLLOCK, K.C. telegram, dated the 8th January, Mr. Bonar Law stated that the Colonial Nursing Association were HON. MR. E. SHELLIM. unable to say when they would be in a position to HON. MR. D. LANDALE. recommend candidates," is it not the fact that (1.)― The Colonial Nursing Association have recently sent HON. MR. LAU CHU PAK. out a Matron and a Sister to the Staff of the Peak HON. -

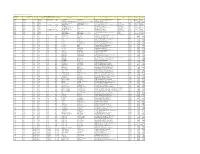

Pulih Sepenuhnya Pada 8:00 Pagi, 21 Oktober 2020 Kumpulan 2

LAMPIRAN A SENARAI KAWASAN MENGIKUT JADUAL PELAN PEMULIHAN BEKALAN AIR DI WILAYAH PETALING, GOMBAK, KLANG/SHAH ALAM, KUALA LUMPUR, HULU SELANGOR, KUALA LANGAT DAN KUALA SELANGOR 19 OKTOBER 2020 WILAYAH : PETALING ANGGARAN PEMULIHAN KAWASAN Kumpulan 1: Kumpulan 2: Kumpulan 3: Pulih Pulih Pulih BIL. KAWASAN sepenuhnya sepenuhnya sepenuhnya pada pada pada 8:00 pagi, 8:00 pagi, 8:00 pagi, 21 Oktober 2020 22 Oktober 2020 23 Oktober 2020 1 Aman Putri U17 / 2 Aman Suria / 3 Angkasapuri / 4 Bandar Baru Sg Buloh Fasa 3 / 5 Bandar Baru Sg. Buloh Fasa 1&2 / 6 Bandar Baru Sri Petaling / 7 Bandar Kinrara / 8 Bandar Pinggiran Subang U5 / 9 Bandar Puchong Jaya / 10 Bandar Tasek Selatan / 11 Bandar Utama / 12 Bangsar South / 13 Bukit Indah Utama / 14 Bukit Jalil / 15 Bukit Jalil Resort / 16 Bukit Lagong / 17 Bukit OUG / 18 Bukit Rahman Putra / 19 Bukit Saujana / 20 Damansara Damai (PJU10/1) / 21 Damansara Idaman / 22 Damansara Lagenda / 23 Damansara Perdana (Raflessia Residency) / 24 Denai Alam / 25 Desa Bukit Indah / 26 Desa Moccis / 27 Desa Petaling / 28 Eastin Hotel / 29 Elmina / 30 Gasing Indah / 31 Glenmarie / 32 Hentian Rehat dan Rawat PLUS (R&R) / 33 Hicom Glenmarie / LAMPIRAN A SENARAI KAWASAN MENGIKUT JADUAL PELAN PEMULIHAN BEKALAN AIR DI WILAYAH PETALING, GOMBAK, KLANG/SHAH ALAM, KUALA LUMPUR, HULU SELANGOR, KUALA LANGAT DAN KUALA SELANGOR 19 OKTOBER 2020 WILAYAH : PETALING ANGGARAN PEMULIHAN KAWASAN Kumpulan 1: Kumpulan 2: Kumpulan 3: Pulih Pulih Pulih BIL. KAWASAN sepenuhnya sepenuhnya sepenuhnya pada pada pada 8:00 pagi, 8:00 pagi, 8:00 -

SITUASI SEMASA LAPORAN MINGGUAN DEMAM DENGGI NEGERI SELANGOR Bagi Minggu Epidemiologi 35/2021 (Tarikh 29.08.21 - 04.09.21)

SITUASI SEMASA LAPORAN MINGGUAN DEMAM DENGGI NEGERI SELANGOR Bagi Minggu Epidemiologi 35/2021 (Tarikh 29.08.21 - 04.09.21) 1. Analisa bilangan kes berdasarkan daerah Pada minggu epidemiologi (ME) 35 iaitu bagi tempoh 29 Ogos hingga 4 September 2021, sejumlah 217 kes demam denggi telah dilaporkan di Negeri Selangor, iaitu penurunan sebanyak 18.4% berbanding 266 kes pada minggu sebelumnya. Sejumlah 10,797 kes demam denggi dilaporkan sehingga ME 35 yang berakhir pada 4 September 2021 iaitu penurunan sebanyak 70.6% ( 25,915 kes) berbanding minggu yang sama tahun 2020 (36,712 kes). Tiada kes kematian dilaporkan dalam tempoh ini. Kumulatif kes kematian sehingga ME 35 adalah dua kes menunjukkan penurunan 94.1 %, berbanding 34 kes kematian pada tempoh yang sama tahun lepas. Jadual 1: Perbandingan bilangan kes demam denggi mengikut daerah berdasarkan ME dan tahun sebelumnya KES KUMULATIF KES SEHINGGA DAERAH ME ME % Peningkatan/ ME ME % Peningkatan/ 34/2021 35/2021 Penurunan 35/2020 35/2021 Penurunan PETALING 88 82 -6.8% 12,942 3,419 -73.6% HULU LANGAT 74 72 -2.7% 7,352 3,044 -58.6% GOMBAK 63 29 -54.0% 5,279 1,986 -62.4% KLANG 25 24 -4.0% 6,303 1,534 -75.7% SEPANG 5 4 -20.0% 2,085 277 -86.7% HULU SELANGOR 6 1 -83.3% 1,220 123 -89.9% KUALA SELANGOR 4 2 -50.0% 721 205 -71.6% KUALA LANGAT 1 3 200.0% 699 202 -71.1% SABAK BERNAM 0 0 111 7 -93.7% SELANGOR 266 217 -18.4% 36,712 10,797 -70.6% ME 34/2021 = (22.08.2021 - 28.08.2021) ME 35/2021 = (29.08.2021 - 04.09.2021) Laporan Mingguan Demam Denggi Negeri Selangor...(MS 1/4) SITUASI SEMASA LAPORAN MINGGUAN DEMAM DENGGI NEGERI SELANGOR Bagi Minggu Epidemiologi 35/2021 (Tarikh 29.08.21 - 04.09.21) 2. -

Malaysia Port Klang Power Station Project (Phase 3 /Phase 3-Stage2)

Malaysia Port Klang Power Station Project (Phase 3 /Phase 3-Stage2) External Evaluator: Taro Tsubogo (KRI International Corp.) Tenaga Nasional Berhad1 Field Survey: March, 2006 1. Project Profile and Japan’s ODA Loan Location of the project site Port Klang (Kapar Phase 3) power station 1.1 Background With the high economic growth, energy demand in the Peninsular Malaysia had grown significantly over the last years with an annual growth rate of 11.4% to 3,447 MW in 1990. Although the growth pace was expected to slow down in the future, energy demand was forecasted to reach 10,448 MW in 2000 with an annual growth rate of 10.6%. Since total installed capacity in 1990 was still 4,576 MW, a serious energy shortage was expected to occur in the future. To fill this gap, construction and expansion of power plants was indispensable option. On the other hand, the Malaysian Government carried out “Four fuel diversification strategy” to enhance the use of indigenous resources and reduce petroleum dependency. The Sixth Malaysia Plan (1991-1995) also envisioned to augment gas supply. The project, to construct 1,000 MW multi-fuel fired power plant, was therefore expected to contribute to both increment of supply capacity and diversification of energy source. 1.2 Objectives The project’s objective was to meet the rapidly increasing demand for energy and assure stable energy supply in the Peninsular Malaysia through construction of a thermal power station (known as Kapar Phase 3 Plant) located adjacent to the existing plants in Port Klang area, and thereby contribute to further economic growth and reducing oil dependence of the country. -

Historical Development of the Federalism System in Malaysia: Prior to Independence

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research (ASSEHR), volume 75 2016 International Seminar on Education, Innovation and Economic Management (SEIEM 2016) Historical Development of the Federalism System in Malaysia: Prior to Independence Wan Kamal Mujani * Wan Hamdi Wan Sulaiman Department of Arabic Studies and Islamic Civilization, Department of Arabic Studies and Islamic Civilization, Faculty of Islamic Studies Faculty of Islamic Studies The National University of Malaysia The National University of Malaysia 43600 Bangi, Malaysia 43600 Bangi, Malaysia [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—This article discusses the development of the Australia etc. According to the book Comparing Federal federalism system in Malaysia prior to independence. During its Systems in the 1990s, Bodin states that even though this administration in Malaya, the British introduced the residents system requires city-states to hand over territorial sovereignty system to facilitate administrative affairs there. Hence in 1895, to the central government, this does not mean that the the Treaty of Federation was made and the Federated Malay territories will lose their identities. Meanwhile, the book States was formed by the British. The introduction of this treaty Decline of the Nation-State asserts that this type of marks the beginning of a new chapter in the development of the administrative system became more influential when the federalism system in Malaya. One of the objectives of this United States of America, which became independent from research is to investigate the development of the federalism British influence in 1776, chose this system to govern the vast system in Malaysia prior to independence. This entire research country. -

RECORDS CODIFICATION MANUAL Prepared by the Office Of

RECORDS CODIFICATION MANUAL Prepared by The Office of Communications and Records Department of State (Adopted January 1, 1950—Revised January 1, 1955) I I CLASSES OF RECORDS Glass 0 Miscellaneous. I Class 1 Administration of the United States Government. Class 2 Protection of Interests (Persons and Property). I Class 3 International Conferences, Congresses, Meetings and Organizations. United Nations. Organization of American States. Multilateral Treaties. I Class 4 International Trade and Commerce. Trade Relations, Treaties, Agreements. Customs Administration. Class 5 International Informational and Educational Relations. Cultural I Affairs and Programs. Class 6 International Political Relations. Other International Relations. I Class 7 Internal Political and National Defense Affairs. Class 8 Internal Economic, Industrial and Social Affairs. 1 Class 9 Other Internal Affairs. Communications, Transportation, Science. - 0 - I Note: - Classes 0 thru 2 - Miscellaneous; Administrative. Classes 3 thru 6 - International relations; relations of one country with another, or of a group of countries with I other countries. Classes 7 thru 9 - Internal affairs; domestic problems, conditions, etc., and only rarely concerns more than one I country or area. ' \ \T^^E^ CLASS 0 MISCELLANEOUS 000 GENERAL. Unclassifiable correspondence. Crsnk letters. Begging letters. Popular comment. Public opinion polls. Matters not pertaining to business of the Department. Requests for interviews with officials of the Department. (Classify subjectively when possible). Requests for names and/or addresses of Foreign Service Officers and personnel. Requests for copies of treaties and other publications. (This number should never be used for communications from important persons, organizations, etc.). 006 Precedent Index. 010 Matters transmitted through facilities of the Department, .1 Telegrams, letters, documents. -

Table of Contents 4.0 Description of the Physical

TABLE OF CONTENTS 4.0 DESCRIPTION OF THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT............................................ 41 4.1 Geology ................................................................................................. 41 4.1.1 Methodology ........................................................................................ 41 4.1.2 Regional Geological Formations........................................................... 42 4.1.3 Local Geological Units ......................................................................... 47 4.1.3.1 Atlantic Coast .......................................................................... 47 4.1.3.2 Gatun Locks.............................................................................. 48 4.1.3.3 Gatun Lake ............................................................................... 49 4.1.3.4 Culebra Cut ......................................................................... ...410 4.1.3.5 Pacific Locks ...........................................................................411 4.1.3.6 Pacific Coast............................................................................412 4.1.4 Paleontological Resources ...................................................................413 4.1.5 Geotechnical Characterization .............................................................417 4.1.6 Tectonics.............................................................................................421 4.2 Geomorphology ..............................................................................................422 -

Climate Change: What Have We Already Observed?

Water resources and ecosystem services examples from Panamá, Puerto Rico, and Venezuela Matthew C. Larsen Director Ecosystem services from forested watersheds mainly product and goods - water resources - wood products - biodiversity, genetic resources, enhanced resilience to wildfire, pathogens, invasive species - recreation, ecotourism - reduced peak river flow during storms - increased availability of groundwater and base flow in streams during dry annual dry season & droughts - reduced soil erosion and landslide probability - buffer to storm surge and tsunamis [forested coastlines] Ecosystem service challenges Land use and governance - deforestation - forest fragmentation - increased wildfire frequency - urban encroachment on forest margins Climate-change - temperature & precipitation, both averages & extremes - intensity, frequency, duration of storms & droughts - sea level rise - rising atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration Climate change: What have we already observed? - 1983 to 2012: warmest 30-year period of last 1400 years northern hemisphere - 1880 to 2012: globally averaged air temps over land & 1928 ocean show warming of 0.85 °C - since 1901: increase in average mid-latitude northern hemisphere land area precipitation - 1979 to 2012: annual mean Arctic sea-ice extent decreased 3.5 to 4.1% per decade 2003 - 1901 to 2010: global mean sea level rose 0.19 m - since mid-19th century: rate of sea level rise has been larger than mean rate during previous 2000 years 2010 Source: IPCC, 2014: Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core South Cascade Glacier, U.S Writing Team, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp. -

Project JYP-1104 SALT INTRUSION in GATUN LAKE a Major Qualifying

Project JYP-1104 SALT INTRUSION IN GATUN LAKE A Major Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science By Assel Akhmetova Cristina Crespo Edwin Muñiz March 11, 2012 Jeanine D. Plummer, Major Advisor Associate Professor, Civil and Environmental Engineering 1. Gatun Lake 2. Salt Intrusion 3. Panama Canal Abstract The expansion of the Panama Canal is adding another lock lane to the canal, allowing passage of larger ships. Increases in the number of transits and the size of the locks may displace more salt from the oceans into the freshwater lake, Gatun Lake, which is a drinking water source for Panama City. This project evaluated future salinity levels in Gatun Lake. Water quality and hydrometeorological data were input into a predictive hydrodynamic software package to project salinity levels in the lake after the new lock system is completed. Modeling results showed that salinity levels are expected to remain in the freshwater range. In the event that the lake becomes brackish, the team designed a water treatment plant using electrodialysis reversal for salt removal and UV light disinfection. ii Executive Summary The Panama Canal runs from the Pacific Ocean in the southeast to the Atlantic Ocean in the northwest over a watershed area containing the freshwater lake, Gatun Lake. The canal facilitates the transit of 36 ships daily using three sets of locks, which displace large volumes of water into and out of Gatun Lake. The displacement of water has the potential to cause salt intrusion into the freshwater Gatun Lake. -

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills As of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills as of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct Supplier Second Refiner First Refinery/Aggregator Information Load Port/ Refinery/Aggregator Address Province/ Direct Supplier Supplier Parent Company Refinery/Aggregator Name Mill Company Name Mill Name Country Latitude Longitude Location Location State AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora Agroaceite Extractora Agroaceite Finca Pensilvania Aldea Los Encuentros, Coatepeque Quetzaltenango. Coatepeque Guatemala 14°33'19.1"N 92°00'20.3"W AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora del Atlantico Guatemala Extractora del Atlantico Extractora del Atlantico km276.5, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Champona, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°35'29.70"N 88°32'40.70"O AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora La Francia Extractora La Francia km. 243, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Buena Vista, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°28'48.42"N 88°48'6.45" O Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - ASOCIACION AGROINDUSTRIAL DE PALMICULTORES DE SABA C.V.Asociacion (ASAPALSA) Agroindustrial de Palmicutores de Saba (ASAPALSA) ALDEA DE ORICA, SABA, COLON Colon HONDURAS 15.54505 -86.180154 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - Cooperativa Agroindustrial de Productores de Palma AceiteraCoopeagropal R.L. (Coopeagropal El Robel R.L.) EL ROBLE, LAUREL, CORREDORES, PUNTARENAS, COSTA RICA Puntarenas Costa Rica 8.4358333 -82.94469444 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - CORPORACIÓN -

Sejarah SELANGO. I

· sejarah SELANGOI. I T I sejarah SELANGOR 0000002549 Sejarah Selangor, SIRI SEJARAH NUSANTARA sejarah , SELANGOR oleh HAJI BUYONG ADIL DEWAN BAHASA DAN PUSTAKA KEMENTERIAN PELAJARAN MALAYSIA KUALA LUMPUR 1981 KK. 291 -783 0102 J disunting oleh ABO. KARIM BIN ABU BAKAR SAHAGIAN BUKU PELAJARAN DEWAN BAHASA DAN PUSTAKA CETAKAN PERTAMA 1971 CETAKAN KEDUA (DENGAN PEMBETULAN) 1981 ©HAKCIPTA HAJI BUYONG ADIL (1971) OICETAK OLEH:· PERCETAKAN BERSATU PRAI, PULAU PINANG. HARGA: $7.00 No. Tel. 362446 8hb. Feb., 1979. DATO' HORMAT RAFEI, (D.P.M.S., S.M.S., J.M.N., A.M.N.,) MENTER! BESAR, SELANGOR. KATA-KATA ALUNAN Y.A.B. DATO' MENTER! BESAR SELANGOR Setakat ini tidak banyak terdapat buku-buku ilmiah yang berharga mengenai sejarah Negeri Selangor yang tersimpan di dalam perbendaharaan kita. Penulisan buku-buku yang berbentuk seperti ini memerlu kan penulis yang benar-benar berpengalaman dan sanggup membuat kajian yang mendalam bagi mempastikan isi kan dungannya dapat dipertanggungjawabkan agar menjadi satu CATITAN zaman yang berharga untuk kenangan generasi yangad a. Buku SEJARAH NEGERI SELANGOR hasil pena Allah yarham Tuan Haji Buyung Adil ini sesungguhnya amatlah bernilai dan mempunyai unsur"unsur akademik yang boleh dijadikan sumber rujukan utama untuk mengenali dan memahamilatar belakang sejarah Negeri Selangor. Kepada sekalian yang berkenaan, terutamanya kepada go Iongan kaum pelajar, saya percaya penerbitan buku ini akan dapat memberikan sumbangan yang besar ertinya kepada tuan-tuan semua. Sekian. I (OATO' HORMAT BIN RAFEI, DPMS, SMS, JMN, AMN) Menteri Besar, Selangor. '"'��� \ i;. I PENDAHULUAN Saya mengucapkan Alhamdulillah dan bersyukur ke had I hrat Allah s.w.t. yang telah memberikan saya tenaga untuk menyusun dan menulis sejarah negeri Selangor yang diterbit kan oleh Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka ini.