Fall 2008 Volume XXII, No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coproduce Or Codevelop Military Aircraft? Analysis of Models Applicable to USAN* Brazilian Political Science Review, Vol

Brazilian Political Science Review ISSN: 1981-3821 Associação Brasileira de Ciência Política Svartman, Eduardo Munhoz; Teixeira, Anderson Matos Coproduce or Codevelop Military Aircraft? Analysis of Models Applicable to USAN* Brazilian Political Science Review, vol. 12, no. 1, e0005, 2018 Associação Brasileira de Ciência Política DOI: 10.1590/1981-3821201800010005 Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=394357143004 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Coproduce or Codevelop Military Aircraft? Analysis of Models Applicable to USAN* Eduardo Munhoz Svartman Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil Anderson Matos Teixeira Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil The creation of the Union of South American Nations (USAN) aroused expectations about joint development and production of military aircraft in South America. However, political divergences, technological asymmetries and budgetary problems made projects canceled. Faced with the impasse, this article approaches features of two military aircraft development experiences and their links with the regionalization processes to extract elements that help to account for the problems faced by USAN. The processes of adoption of the F-104 and the Tornado in the 1950s and 1970s by countries that later joined the European Union are analyzed in a comparative perspective. The two projects are compared about the political and diplomatic implications (mutual trust, military capabilities and regionalization) and the economic implications (scale of production, value chains and industrial parks). -

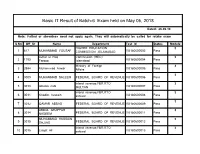

Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam Held on May 05, 2018

Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam held on May 05, 2018 Dated: 26-06-18 Note: Failled or absentees need not apply again. They will automatically be called for retake exam S.No Off_Sr Name Department Test Id Status Module HIGHER EDUCATION 3 1 617 MUHAMMAD YOUSAF COMMISSION ,ISLAMABAD VU180600002 Pass Azhar ul Haq Commission (HEC) 3 2 1795 Farooq Islamabad VU180600004 Pass Ministry of Foreign 3 3 2994 Muhammad Anwar Affairs VU180600005 Pass 3 4 3009 MUHAMMAD SALEEM FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600006 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 5 3010 Ghulan nabi MULTAN VU180600007 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 6 3011 Khadim hussain sahiwal VU180600008 Pass 3 7 3012 QAMAR ABBAS FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600009 Pass ABDUL GHAFFAR 3 8 3014 NADEEM FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600011 Pass MUHAMMAD HUSSAIN 3 9 3015 SAJJAD FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600012 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 10 3016 Liaqat Ali sahiwal VU180600013 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 11 3017 Tariq javed sahiwal VU180600014 Pass 3 12 3018 AFTAB AHMAD FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600015 Pass Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam held on May 05, 2018 Dated: 26-06-18 Muhammad inam-ul- inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 13 3019 haq MULTAN VU180600016 Pass Ministry of Defense (Defense Division) 3 Rawalpindi. 14 4411 Asif Mehmood VU180600018 Pass 3 15 4631 Rooh ul Amin Pakistan Air Force VU180600022 Pass Finance/Income Tax 3 16 4634 Hammad Qureshi Department VU180600025 Pass Federal Board Of Revenue 3 17 4635 Arshad Ali Regional Tax-II VU180600026 Pass 3 18 4637 Muhammad Usman Federal Board Of Revenue VU180600027 -

Global Military Helicopters 2015-16 Market Report Contents

GLOBAL MILITARY HELICOPTERS 2015-16 MARKET REPORT CONTENTS MARKET OVERVIEW 2 MILITARY HELICOPTER KEY REQUIREMENTS 4 EUROPE 5 NORTH AMERICA 10 LATIN AMERICA & THE CARIBBEAN 12 AFRICA 15 ASIA-PACIFIC 16 MIDDLE EAST 21 WORLD MILITARY HELICOPTER HOLDINGS 23 EUROPE 24 NORTH AMERICA 34 LATIN AMERICA & THE CARIBBEAN 36 AFRICA 43 ASIA-PACIFIC 49 MIDDLE EAST 59 EVENT INFORMATION 65 Please note that all information herein is subject to change. Defence IQ endeavours to ensure accuracy wherever possible, but errors are often unavoidable. We encourage readers to contact us if they note any need for amendments or updates. We accept no responsibility for the use or application of this information. We suggest that readers contact the specific government and military programme offices if seeking to confirm the reliability of any data. 1 MARKET OVERVIEW Broadly speaking, the global helicopter market is currently facing a two- pronged assault. The military helicopter segment has been impacted significantly by continued defense budgetary pressures across most traditional markets, and a recent slide in global crude oil prices has impacted the demand for new civil helicopters as well as the level of activity for existing fleets engaged in the offshore oil & gas exploration sector. This situation has impacted industry OEMs significantly, many of which had been working towards strengthening the civil helicopter segment to partially offset the impact of budgetary cuts on the military segment. However, the medium- to long-term view of the market is promising given the presence of strong fundamentals and persistent, sustainable growth drivers. The market for military helicopters in particular is set to cross a technological threshold in the form of next-generation compound helicopters and tilt rotorcraft. -

U.S. Gato Class 26 Submarine Us Navy Measure 32/355-B

KIT 0384 85038410200 GENERAL HULL PAINT GUIDE U.S. GATO CLASS 26 SUBMARINE US NAVY MEASURE 32/355-B In the first few months immediately following the Japanese attack on surface and nine knots under water. Their primary armament consisted Pearl Harbor, it was the U. S. Navy’s submarine force that began unlimited of twenty-four 21-inch torpedoes which could be fired from six tubes in the warfare against Japan. While the surfaces forces regrouped, the submarines bow and four in the stern. Most GATO class submarines typically carried began attacking Japanese shipping across the Pacific. Throughout the war, one 3-inch, one 4-inch, or one 5-inch deck gun. To defend against aircraft American submarines sunk the warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy and while on the surface, one or two 40-mm guns were usually fitted, and cut the lifeline of merchant vessels that provided Japan with oil and other these were supplemented by 20mm cannon as well as .50 caliber and vital raw materials. They also performed other important missions like staging .30 caliber machine guns. Gato class subs were 311'9" long, displaced commando raids and rescuing downed pilots. The most successful of the 2,415 tons while submerged, and carried a crew of eighty-five men. U. S. fleet submarines during World War II were those of the GATO class. Your hightly detailed Revell 1/72nd scale kit can be used to build one of Designed to roam the large expanses of the Pacific Ocean, these submarines four different WWII GATO class submarines: USS COBIA, SS-245, USS were powered by two Diesel engines, generating 5,400 horse power for GROWLER, SS-215, USS SILVERSIDES, SS-236, and the USS FLASHER, operating on the surface, and batteries provided power while submerged. -

TOC, Committee, Awards.Fm

Barringer Medal Citation for Graham Ryder Item Type Article; text Authors Spudis, Paul D. Citation Spudis, P. D. (2003). Barringer Medal Citation for Graham Ryder. Meteoritics & Planetary Science, 38(Supplement), 5-6. DOI 10.1111/j.1945-5100.2003.tb00330.x Publisher The Meteoritical Society Journal Meteoritics & Planetary Science Rights Copyright © The Meteoritical Society Download date 02/10/2021 00:36:25 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Version Final published version Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/655722 66th Meeting of the Meteoritical Society: Awards A5 Barringer Medal Citation for Graham Ryder Graham Ryder, an extraordinary lunar scientist whose One of Graham’s lasting contributions to the community accomplishments revolutionized our understanding of lunar of lunar scientists was the work he conducted in Houston for processes and history, passed away on January 5, 2002 as a over a decade, preparing new catalogs of the lunar samples result of complications from cancer of the esophagus. In his returned by the Apollo 15, 16, and 17 missions. The lunar few years studying the lunar samples, Graham made sample catalogs not only described the nature of over 20,000 fundamental discoveries and came up with new insights that individually numbered lunar samples, but collated all the changed the way we look at the Moon and its history. published data (with full bibliographic references) into a handy Graham was born on January 28, 1949 in Shropshire, compendium that both guided existing projects and spurred England. He received his B.Sc. from the University of Wales new research throughout the 1980s. -

Operation Nickel Grass: Airlift in Support of National Policy Capt Chris J

Secretary of the Air Force Janies F. McGovern Air Force Chief of Staff Gen Larry D. Welch Commander, Air University Lt Gen Ralph Lv Havens Commander, Center for Aerospace Doctrine, Research, and Education Col Sidney J. Wise Editor Col Keith W. Geiger Associate Editor Maj Michael A. Kirtland Professional Staff Hugh Richardson. Contributing Editor Marvin W. Bassett. Contributing Editor John A. Westcott, Art Director and Production Mu linger Steven C. Garst. Art Editor and Illustrator The Airpower Journal, published quarterly, is the professional journal of the United States Air Force. It is designed to serve as an open forum for presenting and stimulating innovative thinking on military doctrine, strategy, tactics, force structure, readiness, and other national defense matters. The views and opinions ex- pressed or implied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be construed as car- rying the official sanction of the Department of Defense, the Air Force, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. Articles in this edition may be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. If repro- duced, the Airpower Journal requests a cour- tesy line. JOURNAL SPRING 1989. Vol. Ill, No. I AFRP 50 2 Editorial 2 Air Interdiction Col Clifford R. Kxieger, USAF 4 Operation Nickel Grass: Airlift in Support of National Policy Capt Chris J. Krisinger, USAF 16 Paradox of the Headless Horseman Lt Col Joe Boyles, USAF Capt Greg K. Mittelman, USAF 29 A Rare Feeling of Satisfaction Maj Michael A. Kirtland, USAF 34 Weaseling in the BUFF Col A. Lee Harrell, USAF 36 Thinking About Air Power Maj Andrew J. -

World Air Forces 2018 in Association with 1 | Flightglobal

WORLD AIR FORCES 2018 IN ASSOCIATION WITH 1 | FlightGlobal Umschlag World Air Forces 2018.indd Alle Seiten 16.11.17 14:23 WORLD AIR FORCES Directory Power players While the new US president’s confrontational style of international diplomacy stoked rivalries, the global military fleet saw a modest rise in numbers: except in North America CRAIG HOYLE LONDON ground-attack aircraft had been destroyed, DATA COMPILED BY DARIA GLAZUNOVA, MARK KWIATKOWSKI & SANDRA LEWIS-RICE Flight Fleets Analyzer shows the action as hav- DATA ANALYSIS BY ANTOINE FAFARD ing had limited materiel effect. It did, however, draw Russia’s ire, as a detachment of its own rinkmanship was the name of the of US Navy destroyers launched 59 Raytheon combat aircraft was using the same Syrian base. game for much of the 2017 calendar Tomahawk cruise missiles towards Syria’s Al- Another spike in rhetoric came in mid-June, year, with global tensions in no small Shayrat air base, targeting its runways and hard- when a Syrian Su-22 was shot down by a US part linked to the head-on approach ened aircraft shelters housing Sukhoi Su-22s. Navy Boeing F/A-18E Super Hornet after attack- B to diplomacy taken by US President Don- Despite initial claims from the Pentagon that ing opposition forces backed by Washington. ald Trump. about one-third of its more than 40 such Syria threatened to target US combat aircraft Largely continuing with the firebrand with advanced surface-to-air missile systems in soundbites which brought him to the Oval Of- Trump and Kim Jong-un the wake of the incident. -

POSTER SESSION 5:30 P.M

Monday, July 27, 1998 POSTER SESSION 5:30 p.m. Edmund Burke Theatre Concourse MARTIAN AND SNC METEORITES Head J. W. III Smith D. Zuber M. MOLA Science Team Mars: Assessing Evidence for an Ancient Northern Ocean with MOLA Data Varela M. E. Clocchiatti R. Kurat G. Massare D. Glass-bearing Inclusions in Chassigny Olivine: Heating Experiments Suggest Nonigneous Origin Boctor N. Z. Fei Y. Bertka C. M. Alexander C. M. O’D. Hauri E. Shock Metamorphic Features in Lithologies A, B, and C of Martian Meteorite Elephant Moraine 79001 Flynn G. J. Keller L. P. Jacobsen C. Wirick S. Carbon in Allan Hills 84001 Carbonate and Rims Terho M. Magnetic Properties and Paleointensity Studies of Two SNC Meteorites Britt D. T. Geological Results of the Mars Pathfinder Mission Wright I. P. Grady M. M. Pillinger C. T. Further Carbon-Isotopic Measurements of Carbonates in Allan Hills 84001 Burckle L. H. Delaney J. S. Microfossils in Chondritic Meteorites from Antarctica? Stay Tuned CHONDRULES Srinivasan G. Bischoff A. Magnesium-Aluminum Study of Hibonites Within a Chondrulelike Object from Sharps (H3) Mikouchi T. Fujita K. Miyamoto M. Preferred-oriented Olivines in a Porphyritic Olivine Chondrule from the Semarkona (LL3.0) Chondrite Tachibana S. Tsuchiyama A. Measurements of Evaporation Rates of Sulfur from Iron-Iron Sulfide Melt Maruyama S. Yurimoto H. Sueno S. Spinel-bearing Chondrules in the Allende Meteorite Semenenko V. P. Perron C. Girich A. L. Carbon-rich Fine-grained Clasts in the Krymka (LL3) Chondrite Bukovanská M. Nemec I. Šolc M. Study of Some Achondrites and Chondrites by Fourier Transform Infrared Microspectroscopy and Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy Semenenko V. -

Realignment and Indian Air Power Doctrine

Realignment and Indian Airpower Doctrine Challenges in an Evolving Strategic Context Dr. Christina Goulter Prof. Harsh Pant Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed or implied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanction of the Department of Defense, Air Force, Air Education and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. This article may be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. If it is reproduced, the Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs requests a courtesy line. ith a shift in the balance of power in the Far East, as well as multiple chal- Wlenges in the wider international security environment, several nations in the Indo-Pacific region have undergone significant changes in their defense pos- tures. This is particularly the case with India, which has gone from a regional, largely Pakistan-focused, perspective to one involving global influence and power projection. This has presented ramifications for all the Indian armed services, but especially the Indian Air Force (IAF). Over the last decade, the IAF has been trans- forming itself from a principally army-support instrument to a broad spectrum air force, and this prompted a radical revision of Indian aipower doctrine in 2012. It is akin to Western airpower thought, but much of the latest doctrine is indigenous and demonstrates some unique conceptual work, not least in the way maritime air- power is used to protect Indian territories in the Indian Ocean and safeguard sea lines of communication. Because of this, it is starting to have traction in Anglo- American defense circles.1 The current Indian emphases on strategic reach and con- ventional deterrence have been prompted by other events as well, not least the 1999 Kargil conflict between India and Pakistan, which demonstrated that India lacked a balanced defense apparatus. -

UNITED STATES SUBMARINE VETERANS INCORPORTATED PALMETTO BASE NEWSLETTER July 2013

OUR CREED: To perpetuate the memory of our shipmates who gave their lives in the pursuit of duties while serving their country. That their dedication, deeds, and supreme sacrifice be a constant source of motivation toward greater accomplishments. Pledge loyalty and patriotism to the United States of America and its constitution. UNITED STATES SUBMARINE VETERANS INCORPORTATED PALMETTO BASE NEWSLETTER July 2013 1 Lost Boats 3 Picture of the Month 10 Members 11 Honorary Members 11 CO’s Stateroom 12 XO’S Stateroom 14 Meeting Attendees 15 Minutes 15 Old Business 15 New Business 16 Good of the Order 16 Base Contacts 17 Birthdays 17 Welcome 17 Binnacle List 17 Quote of the Month 17 Word of the Month 17 Member Profile of the Month 18 Traditions of the Naval Service 21 Dates in U.S. Naval History 23 Dates in U.S. Submarine History 28 Submarine Memorials 48 Monthly Calendar 53 Submarine Trivia 54 Advertising Partners 55 2 USS S-28 (SS-133) Lost on July 4, 1944 with the loss of 50 crew members. She was conducting Lost on: training exercises off Hawaii with the US Coast Guard Cutter Reliance. After S-28 dove for a practice torpedo approach, Reliance lost contact. No 7/4/1944 distress signal or explosion was heard. Two days later, an oil slick was found near where S-28. The exact cause of her loss remains a mystery. US Navy Official Photo BC Patch Class: SS S Commissioned: 12/13/1923 Launched: 9/20/1922 Builder: Fore River Shipbuilding Co Length: 219 , Beam: 22 #Officers: 4, #Enlisted: 34 Fate: Brief contact with S-28 was made and lost. -

World Air Forces Flight 2011/2012 International

SPECIAL REPORT WORLD AIR FORCES FLIGHT 2011/2012 INTERNATIONAL IN ASSOCIATION WITH Secure your availability. Rely on our performance. Aircraft availability on the flight line is more than ever essential for the Air Force mission fulfilment. Cooperating with the right industrial partner is of strategic importance and key to improving Air Force logistics and supply chain management. RUAG provides you with new options to resource your mission. More than 40 years of flight line management make us the experienced and capable partner we are – a partner you can rely on. RUAG Aviation Military Aviation · Seetalstrasse 175 · P.O. Box 301 · 6032 Emmen · Switzerland Legal domicile: RUAG Switzerland Ltd · Seetalstrasse 175 · P.O. Box 301 · 6032 Emmen Tel. +41 41 268 41 11 · Fax +41 41 260 25 88 · [email protected] · www.ruag.com WORLD AIR FORCES 2011/2012 CONTENT ANALYSIS 4 Worldwide active fleet per region 5 Worldwide active fleet share per country 6 Worldwide top 10 active aircraft types 8 WORLD AIR FORCES World Air Forces directory 9 TO FIND OUT MORE ABOUT FLIGHTGLOBAL INSIGHT AND REPORT SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES, CONTACT: Flightglobal Insight Quadrant House, The Quadrant Sutton, Surrey, SM2 5AS, UK Tel: + 44 208 652 8724 Email:LQVLJKW#ÁLJKWJOREDOFRP Website: ZZZÁLJKWJOREDOFRPLQVLJKt World Air Forces 2011/2012 | Flightglobal Insight | 3 WORLD AIR FORCES 2011/2012 The French and Qatari air forces deployed Mirage 2000-5s for the fight over Libya JOINT RESPONSE Air arms around the world reacted to multiple challenges during 2011, despite fleet and budget cuts. We list the current inventories and procurement plans of 160 nations. -

Company Profile

Shaheen Medical Services, Opposite Benazir Bhutto Airport Chaklala, Rawalpindi Phone: +92-51-5405270,5780328, PAF: 3993 http://shaheenmedicalservices.com / Email: [email protected] Page 1 MISSION Gain trust of our valuable clients, with most efficient and ethical services, by providing quality pharmaceutical products with maximum shelf life procured from authentic sources. VISION SMS is continuously striving to be recognized as a leading distributor of pharmaceutical products by focusing on efficient and ethical delivery of services. GOAL To work in collaboration with our worthy partners, to provide high value and premium quality pharmaceutical products to our clients, in order to sustain long-term business relationship. Shaheen Medical Services, Opposite Benazir Bhutto Airport Chaklala, Rawalpindi Phone: +92-51-5405270,5780328, PAF: 3993 http://shaheenmedicalservices.com / Email: [email protected] Page 2 INTRODUCTION Shaheen Foundation, Pakistan Air Force (PAF), was established in 1977 under the Charitable Endowment Act, 1890, essentially to promote welfare for the benefit of serving and retired PAF personnel including its civilian’s employees and their dependents, and to this end generates funds through industrial and commercial enterprises. Since then, it has launched a number of profitable ventures to generate funds necessary for financing the Foundation’s welfare activities. Shaheen Medical Services (SMS) was established to fulfill the pharmaceutical and surgical requirement of Armed forces and public/private sector. Since it’s founding in Rawalpindi in 1996, Shaheen Medical Services, Shaheen Foundation, PAF has become the leading distributor of Pharmaceuticals & Surgical products in Pakistan Air Force Hospitals, with offices in 22 cities nationwide. SMS is a registered member of Rawalpindi Chamber of Commerce and Industries (RCC&I), Export Promotion Bureau (EPB) of Pakistan and Director General Defense Purchase (DGDP).