Alloys of Nickel and Cobalt with Chromium.*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Promotion Effects and Mechanism of Alkali Metals and Alkaline Earth

Subscriber access provided by RES CENTER OF ECO ENVIR SCI Article Promotion Effects and Mechanism of Alkali Metals and Alkaline Earth Metals on Cobalt#Cerium Composite Oxide Catalysts for N2O Decomposition Li Xue, Hong He, Chang Liu, Changbin Zhang, and Bo Zhang Environ. Sci. Technol., 2009, 43 (3), 890-895 • DOI: 10.1021/es801867y • Publication Date (Web): 05 January 2009 Downloaded from http://pubs.acs.org on January 31, 2009 More About This Article Additional resources and features associated with this article are available within the HTML version: • Supporting Information • Access to high resolution figures • Links to articles and content related to this article • Copyright permission to reproduce figures and/or text from this article Environmental Science & Technology is published by the American Chemical Society. 1155 Sixteenth Street N.W., Washington, DC 20036 Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 890–895 Promotion Effects and Mechanism such as Fe-ZSM-5 are more active in the selective catalytic reduction (SCR) of N2O by hydrocarbons than in the - ° of Alkali Metals and Alkaline Earth decomposition of N2O in a temperature range of 300 400 C (3). In recent years, it has been found that various mixed Metals on Cobalt-Cerium oxide catalysts, such as calcined hydrotalcite and spinel oxide, showed relatively high activities. Composite Oxide Catalysts for N2O One of the most active oxide catalysts is a mixed oxide containing cobalt spinel. Calcined hydrotalcites containing Decomposition cobalt, such as Co-Al-HT (9-12) and Co-Rh-Al-HT (9, 11), have been reported to be very efficient for the decomposition 2+ LI XUE, HONG HE,* CHANG LIU, of N2O. -

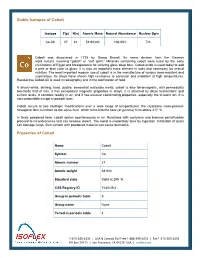

Stable Isotopes of Cobalt Properties of Cobalt

Stable Isotopes of Cobalt Isotope Z(p) N(n) Atomic Mass Natural Abundance Nuclear Spin Co-59 27 32 58.93320 100.00% 7/2- Cobalt was discovered in 1735 by Georg Brandt. Its name derives from the German word kobald, meaning "goblin" or "evil spirit." Minerals containing cobalt were used by the early civilizations of Egypt and Mesopotamia for coloring glass deep blue. Cobalt oxide is used today to add a pink or blue color to glass. It is also an important trace element in soils and necessary for animal nutrition. The most important modern use of cobalt is in the manufacture of various wear-resistant and superalloys. Its alloys have shown high resistance to corrosion and oxidation at high temperatures. Radioactive Cobalt-60 is used in radiography and in the sterilization of food. A silvery-white, shining, hard, ductile, somewhat malleable metal, cobalt is also ferromagnetic, with permeability two-thirds that of iron. It has exceptional magnetic properties in alloys. It is attached by dilute hydrochloric and sulfuric acids. It corrodes readily in air, and it has unusual coordinating properties, especially the trivalent ion. It is noncombustible except in powder form. Cobalt occurs in two allotropic modifications over a wide range of temperatures: the crystalline close-packed- hexagonal form is known as the alpha form, which turns into the beta (or gamma) form above 417 ºC. In finely powdered form, cobalt ignites spontaneously in air. Reactions with acetylene and bromine pentafluoride proceed to incandescence and can become violent. The metal is moderately toxic by ingestion. Inhalation of dusts can damage lungs. -

Cobalt Publications Rejected As Not Acceptable for Plants and Invertebrates

Interim Final Eco-SSL Guidance: Cobalt Cobalt Publications Rejected as Not Acceptable for Plants and Invertebrates Published literature that reported soil toxicity to terrestrial invertebrates and plants was identified, retrieved and screened. Published literature was deemed Acceptable if it met all 11 study acceptance criteria (Fig. 3.3 in section 3 “DERIVATION OF PLANT AND SOIL INVERTEBRATE ECO-SSLs” and ATTACHMENT J in Standard Operating Procedure #1: Plant and Soil Invertebrate Literature Search and Acquisition ). Each study was further screened through nine specific study evaluation criteria (Table 3.2 Summary of Nine Study Evaluation Criteria for Plant and Soil Invertebrate Eco-SSLs, also in section 3 and ATTACHMENT A in Standard Operating Procedure #2: Plant and Soil Invertebrate Literature Evaluation and Data Extraction, Eco-SSL Derivation, Quality Assurance Review, and Technical Write-up.) Publications identified as Not Acceptable did not meet one or more of these criteria. All Not Acceptable publications have been assigned one or more keywords categorizing the reasons for rejection ( Table 1. Literature Rejection Categories in Standard Operating Procedure #4: Wildlife TRV Literature Review, Data Extraction and Coding). No Dose Abdel-Sabour, M. F., El Naggr, H. A., and Suliman, S. M. 1994. Use of Inorganic and Organic Compounds as Decontaminants for Cobalt T-60 and Cesium-134 by Clover Plant Grown on INSHAS Sandy Soil. Govt Reports Announcements & Index (GRA&I) 15, 17 p. No Control Adams, S. N. and Honeysett, J. L. 1964. Some Effects of Soil Waterlogging on the Cobalt and Copper Status of Pasture Plants Grown in Pots. Aust.J.Agric.Res. 15, 357-367 OM, pH Adams, S. -

Historical Development of the Periodic Classification of the Chemical Elements

THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE PERIODIC CLASSIFICATION OF THE CHEMICAL ELEMENTS by RONALD LEE FFISTER B. S., Kansas State University, 1962 A MASTER'S REPORT submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree FASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Physical Science KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 196A Approved by: Major PrafeLoor ii |c/ TABLE OF CONTENTS t<y THE PROBLEM AND DEFINITION 0? TEH-IS USED 1 The Problem 1 Statement of the Problem 1 Importance of the Study 1 Definition of Terms Used 2 Atomic Number 2 Atomic Weight 2 Element 2 Periodic Classification 2 Periodic Lav • • 3 BRIEF RtiVJiM OF THE LITERATURE 3 Books .3 Other References. .A BACKGROUND HISTORY A Purpose A Early Attempts at Classification A Early "Elements" A Attempts by Aristotle 6 Other Attempts 7 DOBEREBIER'S TRIADS AND SUBSEQUENT INVESTIGATIONS. 8 The Triad Theory of Dobereiner 10 Investigations by Others. ... .10 Dumas 10 Pettehkofer 10 Odling 11 iii TEE TELLURIC EELIX OF DE CHANCOURTOIS H Development of the Telluric Helix 11 Acceptance of the Helix 12 NEWLANDS' LAW OF THE OCTAVES 12 Newlands' Chemical Background 12 The Law of the Octaves. .........' 13 Acceptance and Significance of Newlands' Work 15 THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF LOTHAR MEYER ' 16 Chemical Background of Meyer 16 Lothar Meyer's Arrangement of the Elements. 17 THE WORK OF MENDELEEV AND ITS CONSEQUENCES 19 Mendeleev's Scientific Background .19 Development of the Periodic Law . .19 Significance of Mendeleev's Table 21 Atomic Weight Corrections. 21 Prediction of Hew Elements . .22 Influence -

The Development of the Periodic Table and Its Consequences Citation: J

Firenze University Press www.fupress.com/substantia The Development of the Periodic Table and its Consequences Citation: J. Emsley (2019) The Devel- opment of the Periodic Table and its Consequences. Substantia 3(2) Suppl. 5: 15-27. doi: 10.13128/Substantia-297 John Emsley Copyright: © 2019 J. Emsley. This is Alameda Lodge, 23a Alameda Road, Ampthill, MK45 2LA, UK an open access, peer-reviewed article E-mail: [email protected] published by Firenze University Press (http://www.fupress.com/substantia) and distributed under the terms of the Abstract. Chemistry is fortunate among the sciences in having an icon that is instant- Creative Commons Attribution License, ly recognisable around the world: the periodic table. The United Nations has deemed which permits unrestricted use, distri- 2019 to be the International Year of the Periodic Table, in commemoration of the 150th bution, and reproduction in any medi- anniversary of the first paper in which it appeared. That had been written by a Russian um, provided the original author and chemist, Dmitri Mendeleev, and was published in May 1869. Since then, there have source are credited. been many versions of the table, but one format has come to be the most widely used Data Availability Statement: All rel- and is to be seen everywhere. The route to this preferred form of the table makes an evant data are within the paper and its interesting story. Supporting Information files. Keywords. Periodic table, Mendeleev, Newlands, Deming, Seaborg. Competing Interests: The Author(s) declare(s) no conflict of interest. INTRODUCTION There are hundreds of periodic tables but the one that is widely repro- duced has the approval of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and is shown in Fig.1. -

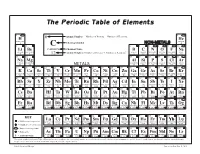

The Periodic Table of Elements

The Periodic Table of Elements 1 2 6 Atomic Number = Number of Protons = Number of Electrons HYDROGENH HELIUMHe 1 Chemical Symbol NON-METALS 4 3 4 C 5 6 7 8 9 10 Li Be CARBON Chemical Name B C N O F Ne LITHIUM BERYLLIUM = Number of Protons + Number of Neutrons* BORON CARBON NITROGEN OXYGEN FLUORINE NEON 7 9 12 Atomic Weight 11 12 14 16 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 SODIUMNa MAGNESIUMMg ALUMINUMAl SILICONSi PHOSPHORUSP SULFURS CHLORINECl ARGONAr 23 24 METALS 27 28 31 32 35 40 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 POTASSIUMK CALCIUMCa SCANDIUMSc TITANIUMTi VANADIUMV CHROMIUMCr MANGANESEMn FeIRON COBALTCo NICKELNi CuCOPPER ZnZINC GALLIUMGa GERMANIUMGe ARSENICAs SELENIUMSe BROMINEBr KRYPTONKr 39 40 45 48 51 52 55 56 59 59 64 65 70 73 75 79 80 84 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 RUBIDIUMRb STRONTIUMSr YTTRIUMY ZIRCONIUMZr NIOBIUMNb MOLYBDENUMMo TECHNETIUMTc RUTHENIUMRu RHODIUMRh PALLADIUMPd AgSILVER CADMIUMCd INDIUMIn SnTIN ANTIMONYSb TELLURIUMTe IODINEI XeXENON 85 88 89 91 93 96 98 101 103 106 108 112 115 119 122 128 127 131 55 56 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 CESIUMCs BARIUMBa HAFNIUMHf TANTALUMTa TUNGSTENW RHENIUMRe OSMIUMOs IRIDIUMIr PLATINUMPt AuGOLD MERCURYHg THALLIUMTl PbLEAD BISMUTHBi POLONIUMPo ASTATINEAt RnRADON 133 137 178 181 184 186 190 192 195 197 201 204 207 209 209 210 222 87 88 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 FRANCIUMFr RADIUMRa RUTHERFORDIUMRf DUBNIUMDb SEABORGIUMSg BOHRIUMBh HASSIUMHs MEITNERIUMMt DARMSTADTIUMDs ROENTGENIUMRg COPERNICIUMCn NIHONIUMNh -

Chromium Compounds Hazard Summary

Chromium Compounds Hazard Summary Chromium occurs in the environment primarily in two valence states, trivalent chromium (Cr III) and hexavalent chromium (Cr VI). Exposure may occur from natural or industrial sources of chromium. Chromium III is much less toxic than chromium (VI). The respiratory tract is also the major target organ for chromium (III) toxicity, similar to chromium (VI). Chromium (III) is an essential element in humans. The body can detoxify some amount of chromium (VI) to chromium (III). The respiratory tract is the major target organ for chromium (VI) toxicity, for acute (short-term) and chronic (long-term) inhalation exposures. Shortness of breath, coughing, and wheezing were reported from a case of acute exposure to chromium (VI), while perforations and ulcerations of the septum, bronchitis, decreased pulmonary function, pneumonia, and other respiratory effects have been noted from chronic exposure. Human studies have clearly established that inhaled chromium (VI) is a human carcinogen, resulting in an increased risk of lung cancer. Animal studies have shown chromium (VI) to cause lung tumors via inhalation exposure. Please Note: The main sources of information for this fact sheet are EPA's Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) (7), which contains information on inhalation chronic toxicity and the RfC and oral chronic toxicity and the RfD, and the carcinogenic effects of chromium including the unit cancer risk for inhalation exposure, EPA's Toxicological Review of Trivalent Chromium and Toxicological Review of Hexavalent Chromium (3), and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry's (ATSDR's) Toxicological Profile for Chromium. (1) Uses The metal chromium is used mainly for making steel and other alloys. -

Soft Magnetic Cobalt-Iron Alloys Vacoflux and Vacodur

SOFT MAGNETIC COBALT-IRON ALLOYS VACOFLUX AND VACODUR ADVANCED MAGNETIC SOLUTIONS THE COMPANY VACUUMSCHMELZE ADVANCED MAGNETIC SOLUTIONS VAC is a leading manufacturer of magnetic materials as well as our refined solutions and their special magnetic and solutions. We passionately advance the tech- properties are the key to making our customers’ nologies of today and tomorrow. As a reliable partner, systems smaller, lighter, more efficient and, last but we work with our customers to develop application not least, safer. Thereby we contribute significantly to solutions that make it possible to meet constantly the saving of resources and the protection of our increasing requirements. We push technical boundaries environment. with groundbreaking solutions. The use of our materials 2 SOFT MAGNETIC COBALT-IRON ALLOYS VACOFLUX® AND VACODUR® THE COMPANY VACUUMSCHMELZE Contents Introduction Page 4 Magnetic properties Page 7 DC magnetic properties of strip material Page 8 DC magnetic properties of solid material Page 9 Specific iron losses of strip material Page 9 Mechanical properties Page 10 Mechanical properties of strip material Page 11 Mechanical properties of solid material Page 11 Physical properties Page 12 Corrosion resistance of VACOFLUX 9 CR Page 13 Processing Page 14 Magnetic final annealing Page 14 Adjusting mechanical properties for VACODUR strip material Page 16 General processing information Page 17 Forms of supply Page 18 SOFT MAGNETIC COBALT-IRON ALLOYS VACOFLUX® AND VACODUR® 3 INTRODUCTION VACUUMSCHMELZE is one of the world’s leading manufac- Our range of soft magnetic materials comprises nickel-iron, turers of special alloys with a particular focus on magnetic silicon-iron and cobalt-iron alloys, as well as amorphous and and specific physical properties. -

Determination of Acute Toxicity of Copper and Cobalt for Tilapia Nilotica

Journal of Bioresource Management Volume 2 Issue 1 Article 3 Determination of Acute Toxicity of Copper and Cobalt for Tilapia nilotica Asif Naseem Rai University of Agriculture Faisalabad, [email protected] Asmat Ullah Hazara University, Mansehra Jibran Haider Forest and Wildlife Department, Gilgit-Baltistan Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/jbm Part of the Biodiversity Commons, and the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Rai, A. N., Ullah, A., & Haider, J. (2015). Determination of Acute Toxicity of Copper and Cobalt for Tilapia nilotica, Journal of Bioresource Management, 2 (1). DOI: 10.35691/JBM.5102.0012 ISSN: 2309-3854 online This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Bioresource Management by an authorized editor of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Determination of Acute Toxicity of Copper and Cobalt for Tilapia nilotica © Copyrights of all the papers published in Journal of Bioresource Management are with its publisher, Center for Bioresource Research (CBR) Islamabad, Pakistan. This permits anyone to copy, redistribute, remix, transmit and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes provided the original work and source is appropriately cited. Journal of Bioresource Management does not grant you any other rights in relation to this website or the material on this website. In other words, all other rights are reserved. For the avoidance of doubt, you must not adapt, edit, change, transform, publish, republish, distribute, redistribute, broadcast, rebroadcast or show or play in public this website or the material on this website (in any form or media) without appropriately and conspicuously citing the original work and source or Journal of Bioresource Management’s prior written permission. -

Silver & Cobalt

JULY 2020 CORPORATE PRESENTATION High-Grade and Technology Leader in Canada’s Silver-Cobalt Heartland SILVER & COBALT CANADA’S SILVER-COBALT HEARTLAND TSX-V CCW | OTC CCWOF | FRANKFURT 4T9B Forward-Looking Statements D I S C L A I M E R Q U A L I F I E D P E R S O N Neither the TSX Venture Exchange nor its Regulation Service Provider (as The technical information in that term is defined in the policies of the TSX Venture Exchange) this corporate presentation was accepts responsibility for the adequacy or accuracy of this material. This prepared under the supervision of presentation may contain forward-looking statements including but not Canada Silver Cobalt Works Inc.’s limited to comments regarding the timing and content of upcoming work President and CEO, Frank J. Basa, programs, geological interpretations, receipt of property titles, potential P.Eng., who is a member of mineral recovery processes, etc. Professional Engineers Ontario and is a Qualified Person in accordance with Forward-looking statements address future events and conditions and National Instrument 43-101. therefore, involve inherent risks and uncertainties. Actual results may differ materially from those currently anticipated in such statements. TSX-V CCW | OTC CCWOF | FRANKFURT 4T9B 2 CCW’s High-Grade Castle East Discovery Meets Robust New Silver Bull Market! The Right Location! Scale Potential Top-Tier Grades Team with Proven Local Success Strategy To Leverage Discovery & Resource TSX-V CCW | OTC CCWOF | FRANKFURT 4T9B 3 Breaking News Matt Halliday New President and Chief Operating Officer • Powerful, expanded team with fresh leadership and energy to take CCW to next level. -

Structures of Cobalt, Zinc and Lead Niobates Based On

1 Structures at the Atomic Level of Cobalt, Zinc and Lead Niobates Raji Heyrovska Institute of Biophysics, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, 135 Kralovopolska, 612 65 Brno, Czech Republic. Email: [email protected] The author has found in recent years that bond lengths are exact sums of the radii of adjacent atoms and or ions, where the ions have Golden ratio based radii. This work was prompted by the exciting observation last year of the Golden ratio in the magnetic properties of cobalt niobate. It is shown here that in cobalt and zinc niobates, cobalt, zinc and oxygen ions have Golden ratio based ionic radii, whereas in lead niobate, all atoms have covalent radii. Also, the angles at the single bond oxygen anion and atom are close to 1080, as in a pentagon. 1-3 The experimental finding of the E8 symmetry in the magnetic properties of cobalt niobate, CoNb2O6 provoked the author's interest to look into the atomic Nature Precedings : hdl:10101/npre.2011.6059.1 Posted 24 Jun 2011 structures of niobates. It was found4-7 in recent years that the Golden sections of the covalent bond lengths d(AA) between two atoms of the same kind are sums of the radii of Pauling's ionic resonance forms8, which are the cations and anions of the atom (A), i.e., d(AA) = d(AA)/φ + d(AA)/φ2, where φ (= 51/2 + 1)/2 is the Golden ratio. In particular, the inter-ionic distances in all alkali halides (M+X-) were shown to be exact sums of the Golden ratio based ionic radii, d(M+) = d(MM)/φ2 and d(X-) = d(XX)/φ. -

The Influence of Heavy Metals and Organic Matter on Hexavalent

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archivio della ricerca- Università di Roma La Sapienza 289 A publication of CHEMICAL ENGINEERING TRANSACTIONS VOL. 47, 2016 The Italian Association of Chemical Engineering Online at www.aidic.it/cet Guest Editors: Angelo Chianese, Luca Di Palma, Elisabetta Petrucci, Marco Stoller Copyright © 2016, AIDIC Servizi S.r.l., ISBN 978-88-95608-38-9; ISSN 2283-9216 DOI: 10.3303/CET1647049 The Influence of Heavy Metals and Organic Matter on Hexavalent Chromium Reduction by Nano Zero Valent Iron in Soil Mouhamadou Thierno Gueyea, Luca Di Palmab, Gunel Allahverdeyevac, Irene b b b b Bavasso , Elisabetta Petrucci , Marco Stoller , Giorgio Vilardi a Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar (UCAD), Dakar Fann, Senegal b Sapienza Università di Roma, Dipartimento di Ingegneria Chimica Materiali Ambiente, via Eudossiana 18, 00184 Roma c Baku State University, 23 Khalilov St., Baku, Azerbaijan During the last decades great attention has been payed at evaluating the feasibility of Cr(VI) reduction in soil 0 by nano zero valent iron (nZVI). An inhibitory effect on the Cr(VI) reduction by Fe nanoparticles is generally shown in the presence of high level of heavy metals and natural organic matter in soil. Heavy metals in the environment can react with nZVI by redox reactions, precipitation/dissolution reactions, and adsorption/desorption phenomena. As a result of the presence of metals as Ni, Pb, a decrease in the rate of Cr(VI) reduction was observed. Hence, in the present study, experimental tests of Cr(VI) reduction by nZVI in the presence of selected heavy metals, such as nickel and lead, and in the presence of high level of organic matter, are presented and discussed.