Manufacturing: the New Consensus a Blueprint for Better Jobs and Higher Wages June 2013 Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

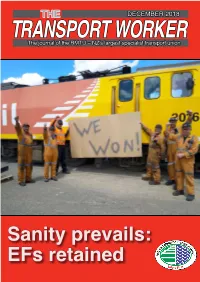

Sanity Prevails: Efs Retained 2 Contents Editorial ISSUE 4 • DECEMBER 2018

THE DECEMBER 2018 TRANSPORThe journal of the RMTU – NZ'sT largest WORKER specialist transport union Sanity prevails: EFs retained 2 CONTENTS EDITORIAL ISSUE 4 • DECEMBER 2018 12 SHANE JONES DOES HUTT SHOPS MP Shane Jones paid a visit to Hutt Workshops to familiarise himself with what the Work- shops can do and the affects of HPHE at the work face. 14 BIENNIAL CONFERENCE Wayne Butson General secretary RMTU Once again your Union held a very successful conference in Wellington with Plenty of positives a line-up of inspiring speakers. HIS time last year I wrote that rail, coastal shipping, public transport and regional development would see real gains during this Parliamentary term 36 MONGOLIAN MAGIC and that by late 2018 it would be a great time to be an RMTU member. Pare-Ana Bysterveld The good news is that by and large all has come to pass. (pictured) reports So it was with great joy that I was a member of the RMTU team to attend the Labour TParty Conference in Dunedin this year. That was its official name. However, we, and from the ICLS conference in a number of other parties, were calling it the Labour and RMTU Victory Conference. Mongolia where she Labour because, despite the nay-sayers, we remain with a viable coalition Gov- was blown away in ernment with partners working well together, and who, just one week prior, had more ways than one. announced a $35m funding of the rejuvenation of the North Island Main Trunk electric locomotives. When we launched the campaign to save the electric locos in 2016 I certainly did not fully appreciate the difficulty we would have in getting the victory and, secondly how we would pick up support from a wide range of community and environmental COVER PHOTOGRAPH: RMTU members of the groups, academics and other like-minded individuals. -

Thrf-2019-1-Winners-V3.Pdf

TO ALL 21,100 Congratulations WINNERS Home Lottery #M13575 JohnDion Bilske Smith (#888888) JohnGeoff SmithDawes (#888888) You’ve(#105858) won a 2019 You’ve(#018199) won a 2019 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 KymJohn Tuck Smith (#121988) (#888888) JohnGraham Smith Harrison (#888888) JohnSheree Smith Horton (#888888) You’ve won the Grand Prize Home You’ve(#133706) won a 2019 You’ve(#044489) won a 2019 in Brighton and $1 Million Cash BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 GaryJohn PeacockSmith (#888888) (#119766) JohnBethany Smith Overall (#888888) JohnChristopher Smith (#888888)Rehn You’ve won a 2019 Porsche Cayenne, You’ve(#110522) won a 2019 You’ve(#132843) won a 2019 trip for 2 to Bora Bora and $250,000 Cash! BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 Holiday for Life #M13577 Cash Calendar #M13576 Richard Newson Simon Armstrong (#391397) Win(#556520) a You’ve won $200,000 in the Cash Calendar You’ve won 25 years of TICKETS Win big TICKETS holidayHolidays or $300,000 Cash STILL in$15,000 our in the Cash Cash Calendar 453321 Annette Papadulis; Dernancourt STILL every year AVAILABLE 383643 David Allan; Woodville Park 378834 Tania Seal; Wudinna AVAILABLE Calendar!373433 Graeme Blyth; Para Hills 428470 Vipul Sharma; Mawson Lakes for 25 years! 361598 Dianne Briske; Modbury Heights 307307 Peter Siatis; North Plympton 449940 Kate Brown; Hampton 409669 Victor Sigre; Henley Beach South 371447 Darryn Burdett; Hindmarsh Valley 414915 Cooper Stewart; Woodcroft 375191 Lynette Burrows; Glenelg North 450101 Filomena Tibaldi; Marden 398275 Stuart Davis; Hallett Cove 312911 Gaynor Trezona; Hallett Cove 418836 Deidre Mason; Noarlunga South 321163 Steven Vacca; Campbelltown 25 years of Holidays or $300,000 Cash $200,000 in the Cash Calendar Winner to be announced 29th March 2019 Winners to be announced 29th March 2019 Finding cures and improving care Date of Issue Home Lottery Licence #M13575 2729 FebruaryMarch 2019 2019 Cash Calendar Licence ##M13576M13576 in South Australia’s Hospitals. -

The Eagle 2013 the EAGLE

VOLUME 95 FOR MEMBERS OF ST JOHN’S COLLEGE The Eagle 2013 THE EAGLE Published in the United Kingdom in 2013 by St John’s College, Cambridge St John’s College Cambridge CB2 1TP johnian.joh.cam.ac.uk Telephone: 01223 338700 Fax: 01223 338727 Email: [email protected] Registered charity number 1137428 First published in the United Kingdom in 1858 by St John’s College, Cambridge Designed by Cameron Design (01284 725292, www.designcam.co.uk) Printed by Fisherprint (01733 341444, www.fisherprint.co.uk) Front cover: Divinity School by Ben Lister (www.benlister.com) The Eagle is published annually by St John’s College, Cambridge, and is sent free of charge to members of St John’s College and other interested parties. Page 2 www.joh.cam.ac.uk CONTENTS & MESSAGES CONTENTS & MESSAGES THE EAGLE Contents CONTENTS & MESSAGES Photography: John Kingsnorth Page 4 johnian.joh.cam.ac.uk Contents & messages THE EAGLE CONTENTS CONTENTS & MESSAGES Editorial..................................................................................................... 9 Message from the Master .......................................................................... 10 Articles Maggie Hartley: The best nursing job in the world ................................ 17 Esther-Miriam Wagner: Research at St John’s: A shared passion for learning......................................................................................... 20 Peter Leng: Living history .................................................................... 26 Frank Salmon: The conversion of Divinity -

Professor Richard Epstein and the New Zealand Employment Contract

Wailes: Professor Richard Epstein and the New Zealand Employment Contract PROFESSOR RICHARD EPSTEIN AND THE NEW ZEALAND EMPLOYMENT CONTRACTS ACT: A CRITIQUE NICK WAILES* Penelope Brook, one of the major proponents of radical reform in the New Zealand labor law system, has characterized the New Zealand Em- ployment Contracts Act (ECA) as an "incomplete revolution."' She argues that this "incompleteness" stems from the retention of a specialist labor law jurisdiction and the failure to frame the Act around the principle of contract at will.2 The emphasis placed on these two issues-specialist jurisdiction and contract at will-demonstrates the influence arguments made by Chi- cago Law Professor, Richard Epstein, have played on labor law reform in New Zealand. Despite reservations about its final form, Brook gives her support to the ECA, precisely because it operationalizes some of Epstein's ideas. It has been generally acknowledged that ideas like those of Epstein played a significant role in the introduction of the ECA in New Zealand. However, while critics of the ECA have acknowledged the importance of Epstein's ideas in the debate which led up to the passing of the Act, few at- tempts have been made to outline clearly or critique Epstein's views. This Paper attempts to fill this lacuna by providing a critique of the behavioral assumptions that Epstein brings to his analysis of labor law. The first sec- * The Department of Industrial Relations, The University of Sydney, Australia. This is an amended version of Nick Wailes, The Case Against Specialist Jurisdictionfor Labor Law: PhilosophicalAssumptions of a Common Law for Labor Relations, 19 N.Z.J. -

GLOBALISATION, SOVEREIGNTY and the TRANSFORMATION of NEW ZEALAND FOREIGN POLICY Robert G

Working Pape Working GLOBALISATION, SOVEREIGNTY AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF NEW ZEALAND FOREIGN POLICY Robert G. Patman Centre for Strategic Studies: New Zealand r Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. No.21/05 CENTRE FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES NEW ZEALAND Working Papers The Centre for Strategic Studies Working Paper series is designed to give a forum for scholars and specialists working on issues related directly to New Zealand’s security, broadly defined, and to the Asia-Pacific region. The Working Papers represent ‘work in progress’ and as such may be altered and expanded after feedback before being published elsewhere. The opinions expressed and conclusions drawn in the Working Papers are solely those of the writer. They do not necessarily represent the views of the Centre for Strategic Studies or any other organisation with which the writer may be affiliated. For further information or additional copies of the Working Papers please contact: Centre for Strategic Studies: New Zealand Victoria University of Wellington PO Box 600 Wellington New Zealand. Tel: 64 4 463 5434 Fax: 64 4 463 5737 Email: [email protected] Website: www.vuw.ac.nz/css/ Centre for Strategic Studies Victoria University of Wellington 2005 © Robert G. Patman ISSN 1175-1339 Desktop Design: Synonne Rajanayagam Globalisation, Sovereignty, and the Transformation of New Zealand Foreign Policy Working Paper 21/05 Abstract Structural changes in the global system have raised a big question mark over a traditional working principle of international relations, namely, state sovereignty. With the end of the Cold War and the subsequent break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991, the US has been left as the world’s only superpower. -

Trans Tasman Politics, Legislation, Trade, Economy Now in Its 50Th Year 22 March Issue • 2018 No

www.transtasman.co.nz Trans Tasman Politics, Legislation, Trade, Economy Now in its 50th year 22 March Issue • 2018 No. 18/2115 ISSN 2324-2930 Comment Tough Week For Ardern If Jacinda Ardern is in the habit of asking herself whether she’s doing a good job at the end of each week, she’ll have had the first one when the answer has probably been no. It has been a week in which she has looked less like a leader than she has at any time so far in her time as head of the Labour Party and then Prime Minister. Jacindamania is fading. The tough reality of weekly politics is taking over. The Party apparatus has dropped her in it – but she seems powerless to get rid of the source of the problem, because while she is Prime Minister, she’s not in charge of the party. The party seems to have asserted its rights to do things its own way, even if this means keeping the PM in the dark about a sex assault claim after an alleged incident at a party function. Even a Cabinet Minister knew and didn’t tell her. This made Ardern look powerless. Her coalition partner, Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Winston Peters also led her a merry dance this week over the Russia Free Trade agreement the two parties agreed to pursue as part of their coalition agree- ment. Peters unfortunately chose a week in which Russia was accused of a deadly nerve agent attack on one of its former spies in Britain to up the ante on pushing the FTA forward. -

Publ 408/Pols 436 State and the Economy – Globalisation Issues

School of Government PUBL 408/POLS 436 STATE AND THE ECONOMY – GLOBALISATION ISSUES Trimester 1 2007 COURSE OUTLINE Contact Details Course Co-ordinator: Dr John Wilson RH 212 Tel: 04 463 5082 [email protected] [email protected] Office hours: Wednesday 1.00pm – 2.30pm; other times by appointment. Administrator: Francine McGee RH 821 (Reception) 04 463 – 6599 [email protected] Class Times and Room Numbers Lectures: Wednesday 2.40pm – 4.30pm GB117 Additional information will be posted on the departmental notice board, or announced in class. Course aims and objectives The state and the market represent two different approaches to organising human behaviour, and the relationship between them has always affected the conduct of public policy. A key theme of the course is the way in which states manage their economic development within an international context increasingly characterised by patterns of globalisation. While globalisation may enhance a nation’s economic prosperity, it also has implications for the ability of national governments to autonomously pursue economic, social, and environmental objectives. Case studies examine how the pursuit of economic development goals can conflict with wider policy objectives in the energy, environmental, trade, and social policy areas. 1 By the end of the course, students should be able to: appreciate the evolution of the state- economy relationship: understand the role of government in managing the economy; understand and critique the challenges posed by globalisation to national and economic development; show to what extent states can autonomously pursue their public policy goals in the era of globalisation. -

Nzjer, 2014, 39(1)

Contents Page: NZJER, 2014, 39(1) Name Title Page Number Felicity Lamm, Erling Editorial Rasmussen and Rupert 1 Tipples Raymond Markey, Exploring employee participation Candice Harris, Herman and work environment in hotels: 2-20 Knudsen, Jens Lind and Case studies from Denmark and David Williamson New Zealand Erling Rasmussen, The major parties: National’s and Michael Fletcher and Labour’s employment relations 21-32 Brian Hannam policies Julienne Molineaux and The Minor Parties: Policies, Peter Skilling Priorities and Power 33-51 Danaë Anderson and Are vulnerable workers really Tipples protected in New Zealand? 52-67 Nigel Haworth and Commentary – The New Zealand Brenda Pilott Public Sector: Moving Beyond 68-78 New Public Management? Venkataraman Nilakant, Research Note: Conceptualising Bernard Walker, Kate Adaptive Resilience using 79-86 van Heugen, Rosemar Grounded Theory Baird and Herb de Vries Sir Geoffrey Palmer Eulogy for the Rt Hon Sir Owen Woodhouse 87-91 Ross Wilson Obituary 92-93 New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 39(1): 1 Editorial This issue shows the diverse range of employment relations issues in New Zealand. We begin with Markey et al.’s paper which reports on research into employee participation and well-being in the New Zealand hospitality sector and then compares it to the famous ‘Danish Model’. While Danish formal employee participation structures are clearly well embedded, this article shows that there is a more complex picture with several direct forms of participation available in New Zealand hospitality firms. However, the article also indicates that some of the direct forms of participation can be associated with negative well-being effects. -

Annual Report 2013

ANNUAL REPORT 2013 The Europe Institute is a multi-disciplinary research institute that brings together researchers from a large number of different departments and faculties, including Accounting and Finance, Anthropology, Art History, International Business and Management, Economics, Education, Engineering, European Languages and Literatures, Film, Media and TV Studies, Law, Medical and Health Sciences and Political Studies. The mission of the Institute is to promote research, scholarship and teaching on contemporary Europe and EU-related issues, including social and economic relations, political processes, trade and investment, security, human rights, education, culture and collaboration on shared Europe-New Zealand concerns. The goals of the Institute are to: • Initiate and organise a programme of research activities at the University of Auckland and in New Zealand • Build and sustain our network of expertise on contemporary European issues • Initiate and coordinate new research projects • Provide support and advice for developing research programmes • Support seminars, public lectures and other events on contemporary Europe Contents Staff of the Institute ................................................................................................................................ 2 Message from the Director ..................................................................................................................... 4 Major Projects ........................................................................................................................................ -

Wednesday, April 22, 2020

TE NUPEPA O TE TAIRAWHITI WEDNESDAY, APRIL 22, 2020 HOME-DELIVERED $1.90, RETAIL $2.20 Wairoa Mayor harassment investigation cost $55,000 DETAILS around Wairoa Mayor Craig Little’s Code of Conduct investigation over alleged harassment that cost ratepayers $55,000 in settlement and legal costs have been revealed. Stuff reported the investigation was sparked by a female employee after she complained to Wairoa District Council’s chief executive officer about Mr Little’s alleged behaviour towards her in mid-2017. The complainant claimed the Mayor’s behaviour breached the standards of ethical behaviour and the respect for others outlined in the council’s Code of Conduct. A preliminary assessment of the complaint by council concluded a full investigation was warranted and an independent investigator was instructed to carry this out. But before that went ahead the employee, who no longer works at the council, withdrew the complaint and said they had no objection to the council ceasing the investigation and taking no further action. The council spent $55,652, which included an undisclosed sum paid in compensation to the complainant, as well as legal fees incurred by the council and the complainant. Stuff reported that Mr Little would not comment and referred a request for comment to Wairoa District Council chief executive officer Steven May. In a statement, the council said the investigation was stopped after the complainant withdrew her complaint and DIVERSIFYING TO MEET DEMAND: Easts Outdoor Work and Leisure in Makaraka has adapted to the “the employment relationship between the Covid-19 times by making PVC face shields. -

NZ Politics Daily: 7 November 2016 Today's Content

NZ Politics Daily: 7 November 2016 Page 1 of 330 NZ Politics Daily: 7 November 2016 Today’s content Labour Party conference Claire Trevett (Herald): Andrew Little: No frills, but not budget brand Claire Trevett (Herald): Look who's back: Sir Michael Cullen returns to duty with a warning for Grant Robertson Claire Trevett (Herald): Andrew Little revs up party faithful: 'It's neck and neck' Richard Harman (Politik): Inside Labour's conference Jane Patterson (RNZ): Does Labour truly believe it can beat Key? Toby Manhire (The Spinoff): Andrew Little rolls out the rug for a Labour tilt at power in 2017 Vernon Small (Stuff): Labour puts storms behind it as Little navigates into calmer waters Herald: Editorial: Labour needs to look more like Auckland Claire Trevett (Herald): Labour and how to win Auckland in 50 minutes Newshub: Labour compulsory voting policy just a quick fix - expert Adriana Weber (RNZ): Business critical of Labour's proposed no training tax Alex Mason (Newstalk ZB): Labour's job policy "wrong policy at the wrong time" - Joyce Jenna Lynch (Newshub): Did Labour plagiarise Newshub? Claire Trevett (Herald): devilish detail puts Grant Robertson in a fresh hell Newshub: Has Labour got its youth work scheme numbers right? Andrea Vance (TVNZ): Labour proposing new tax targeting business employing foreign workers TVNZ: Labour keen to embrace Greens under MMP Claire Trevett (Herald): Grant Robertson: training levy not part of crackdown on migrant labour Vernon Small (Stuff): Labour offers six months paid work to young long-term unemployed -

Hobbit Law”: Exploring Non-Standard Employment

The “Hobbit Law”: Exploring Non-standard Employment Contents Page: NZJER, 2011, 36(3) Name Title Page Number Editorial: Introducing the Forum Bernard Walker & 1-4 Rupert Tipples A Synopsis of The Hobbit Dispute 5-13 A.F Tyson How does non-standard employment affect 14-29 Bernard Walker workers? A consideration of the evidence The Hobbit Dispute 30-33 Helen Kelly One Law to Rule them All 34-36 Kate Wilkinson Non-standard Work: an Employer 37-43 Barbara Burton Perspective Insights into Contracting and the Effect on 44-58 Darien Fenton Workers Independent Contractor vs. Employee 59-72 Peter Kiely “...Where the Shadows lie”: Confusion, 73-90 Pam Nuttall misunderstanding, and misinformation about workplace status Constitutional Implications of „The Hobbit‟ 91-99 Margaret Wilson Legislation A Political Economy of „The Hobbit‟ 100-109 Nigel Haworth Dispute John Murrie Book Review of Employment 110-112 Relationships: Workers, Unions and Employers in New Zealand New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations 36(3): 1-4 Introducing the Forum The emergence of this Issue High profile disputes bring less-recognised employment relations topics to the forefront of public attention. The 2010 dispute surrounding the Hobbit production involved one of the world‟s major screen productions, an international boycott by actors, and the possibility of the production being relocated to another country. As such, it formed a major event in employment relations. The passion and controversy associated with the dispute gained international attention, creating a renewed interest in the relationships between business, Government, and unions as well as rekindling the debates surrounding non-standard employment and collective representation.