GLOBALISATION, SOVEREIGNTY and the TRANSFORMATION of NEW ZEALAND FOREIGN POLICY Robert G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kiwisaver – Issues for Supplementary Drafting Instructions

PolicyP AdviceA DivisionD Treasury Report: KiwiSaver – Issues for Supplementary Drafting Instructions Date: 21 October 2005 Treasury Priority: High Security Level: IN-CONFIDENCE Report No: T2005/1974, PAD2005/186 Action Sought Action Sought Deadline Minister of Finance Agree to all recommendations 28 October 2005 Refer to Ministers of Education and Housing Minister of Commerce Agree to recommendations r to dd 28 October 2005 Minister of Revenue Agree to recommendations e to q 28 October 2005 Associate Minister of Finance Note None (Hon Phil Goff) Associate Minister of Finance Note None (Hon Trevor Mallard) Associate Minister of Finance Note None (Hon Clayton Cosgrove) Contact for Telephone Discussion (if required) Name Position Telephone 1st Contact Senior Analyst, Markets, Infrastructure 9 and Government, The Treasury Senior Policy Analyst, Regulatory and Competition Policy Branch, MED Michael Nutsford Policy Manager, Inland Revenue Enclosure: No Treasury:775533v1 IN-CONFIDENCE 21 October 2005 SH-13-0-7 Treasury Report: KiwiSaver – Issues for Supplementary Drafting Instructions Executive Summary Officials have provided the Parliamentary Counsel Office (PCO) with an initial set of drafting instructions on KiwiSaver. However, in preparing these drafting instructions, a range of further issues came to light. We are seeking decisions on these matters now so that officials can provide supplementary drafting instructions to PCO by early November. Officials understand that a meeting may be arranged between Ministers and officials for late next week to discuss the issues contained in this report and on the overall KiwiSaver timeline. A separate report discussing the timeline for KiwiSaver and the work on the taxation of qualifying collective investment vehicles will be provided to you early next week. -

1 NEWS Colmar Brunton Poll 22 – 26 May 2021

1 NEWS Colmar Brunton Poll 22 – 26 May 2021 Attention: Television New Zealand Contact: (04) 913-3000 Release date: 27 May 2021 Level One 46 Sale Street, Auckland CBD PO Box 33690 Takapuna Auckland 0740 Ph: (09) 919-9200 Level 9, Legal House 101 Lambton Quay PO Box 3622, Wellington 6011 Ph: (04) 913-3000 www.colmarbrunton.co.nz Contents Contents .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Methodology summary ................................................................................................................................... 2 Summary of results .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Key political events ................................................................ .......................................................................... 4 Question order and wording ............................................................................................................................ 5 Party vote ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 Preferred Prime Minister ................................................................................................................................. 8 Public Sector wage freeze ............................................................................................................................. -

Adapting to Institutional Change in New Zealand Politics

21. Taming Leadership? Adapting to Institutional Change in New Zealand Politics Raymond Miller Introduction Studies of political leadership typically place great stress on the importance of individual character. The personal qualities looked for in a New Zealand or Australian leader include strong and decisive action, empathy and an ability to both reflect the country's egalitarian traditions and contribute to a growing sense of nationhood. The impetus to transform leaders from extraordinary people into ordinary citizens has its roots in the populist belief that leaders should be accessible and reflect the values and lifestyle of the average voter. This fascination with individual character helps account for the sizeable biographical literature on past and present leaders, especially prime ministers. Typically, such studies pay close attention to the impact of upbringing, personality and performance on leadership success or failure. Despite similarities between New Zealand and Australia in the personal qualities required of a successful leader, leadership in the two countries is a product of very different constitutional and institutional traditions. While the overall trend has been in the direction of a strengthening of prime ministerial leadership, Australia's federal structure of government allows for a diffusion of leadership across multiple sources of influence and power, including a network of state legislatures and executives. New Zealand, in contrast, lacks a written constitution, an upper house, or the devolution of power to state or local government. As a result, successive New Zealand prime ministers and their cabinets have been able to exercise singular power. This chapter will consider the impact of recent institutional change on the nature of political leadership in New Zealand, focusing on the extent to which leadership practices have been modified or tamed by three developments: the transition from a two-party to a multi-party parliament, the advent of coalition government, and the emergence of a multi-party cartel. -

Clark Vader and the Helengrad Labour Lesbians

Clark Vader and the Helengrad Labour Lesbians Anatomy of a political-symbolic hate campaign Lewis Stoddart – [email protected] 2008-07-20 (This is a slightly revised edition of a research paper submitted toward a graduate diploma in political science at Victoria University of Wellington on 15 October 2007) And yet the rage that one felt was an abstract, undirected emotion which could be switched from one object to another like the flame of a blowlamp. — George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four Clark Vader and the Helengrad Labour Lesbians Lewis Stoddart – [email protected] – 2008-07-20 Contents Introduction 2 Methodology 3 Discourse . 3 Political symbols . 7 Communist lesbian dictator 9 Communist . 9 Feminazi . 10 Totalitarian . 10 Ideological conspiracy . 11 Information control . 12 Corruption . 14 Nanny State . 15 Violence . 17 Convergence . 18 Symbolic promotion 19 Hate................................................... 20 A theory of symbolic promotion . 21 Hope................................................... 22 Appendix A: Data collection 25 Appendix B: Symbolic vocabulary 26 Appendix C: Source audio 29 Bibliography 33 1 Clark Vader and the Helengrad Labour Lesbians Lewis Stoddart – [email protected] – 2008-07-20 Helen Clark, the first woman elected Prime Minister of New Zealand, has for decades been the subject of political attacks. These have been made on the basis of her history as an academic, her gender, domestic status and personal life, and not least her politics. John Banks and Lindsay Perigo, in their host roles on the Radio Pacific breakfast talk show The First Edition,1 crystallised various of these attack strategies into a characterisation which I describe as ‘communist lesbian dictator’. This is not to say that Banks or Perigo ever owned or controlled the discourse which feeds this charac- terisation; indeed it is quite widespread, enough so that caricatures of Clark2 routinely make fun of her ‘masculine’ characteristics, her ‘ruthlessness’, her tendency to wear red blazers, and other such symbolic matter. -

'About Turn': an Analysis of the Causes of the New Zealand Labour Party's

Newcastle University e-prints Date deposited: 2nd May 2013 Version of file: Author final Peer Review Status: Peer reviewed Citation for item: Reardon J, Gray TS. About Turn: An Analysis of the Causes of the New Zealand Labour Party's Adoption of Neo-Liberal Policies 1984-1990. Political Quarterly 2007, 78(3), 447-455. Further information on publisher website: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com Publisher’s copyright statement: The definitive version is available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-923X.2007.00872.x Always use the definitive version when citing. Use Policy: The full-text may be used and/or reproduced and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not for profit purposes provided that: A full bibliographic reference is made to the original source A link is made to the metadata record in Newcastle E-prints The full text is not changed in any way. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Robinson Library, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, Newcastle upon Tyne. NE1 7RU. Tel. 0191 222 6000 ‘About turn’: an analysis of the causes of the New Zealand Labour Party’s adoption of neo- liberal economic policies 1984-1990 John Reardon and Tim Gray School of Geography, Politics and Sociology Newcastle University Abstract This is the inside story of one of the most extraordinary about-turns in policy-making undertaken by a democratically elected political party. -

Gender Stereotypes and Media Bias in Women's

Gender Stereotypes and Media Bias in Women’s Campaigns for Executive Office: The 2009 Campaign of Dora Bakoyannis for the Leadership of Nea Dimokratia in Greece by Stefanos Oikonomou B.A. in Communications and Media Studies, February 2010, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of College of Professional Studies of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Professional Studies August 31, 2014 Thesis directed by Michael Cornfield Associate Professor of Political Management Acknowledgments I would like to thank my parents, Stella Triantafullopoulou and Kostas Oikonomou, to whom this work is dedicated, for their continuous love, support, and encouragement and for helping me realize my dreams. I would also like to thank Chrysanthi Hatzimasoura and Philip Soucacos, for their unyielding friendship, without whom this work would have never been completed. Finally, I wish to express my gratitude to Professor Michael Cornfield for his insights and for helping me cross the finish line; Professor David Ettinger for his guidance during the first stage of this research and for helping me adjust its scope; and the Director of Academic Administration at The Graduate School of Political Management, Suzanne Farrand, for her tremendous generosity and understanding throughout this process. ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………..ii List of Figures…………………………………………………………………………….vi List of Tables…………………………………………………………………………….vii -

What Makes a Good Prime Minister of New Zealand? | 1 Mcguinness Institute Nation Voices Essay Competition

NATION VOICES ESSAY COMPETITION What makes a good About the author Brad is studying towards a BCom/ Prime Minister of BA majoring in Economics, Public Policy, International New Zealand? Relations and Political Science. He is a 2016 Brad Olsen Queen’s Young Leader for New Zealand after his work with territorial authorities, central government organizations and NGOs. He’s passionate about youth voice and youth participation in wider society. Leadership is a complex concept, necessitating vast amounts of patience, determination, and passion to work with others towards a position of improvement in the chosen field of expertise or service. Leaders not only bear the burden of setting the direction of actions or inactions for their team, but are also often accountable to stakeholders, with varying degrees of accountability and size of the cohort to which a leader is accountable. However, there is no more complex job in existence than the leadership of a country like New Zealand — this burden falls squarely on the Prime Minister, in charge of policy both foreign and domestic, all the while totally accountable to each and every citizen in his or her realm. Unsurprisingly, some make a better fist of it than others, with the essence of this good leadership a highly sought commodity. Three areas are critical to ensuring a Prime Minister can effectively lead — a measurement of how ‘good’ they are at their job — these fall under the umbrellas of political, social, and economic leadership ability. Politically, Prime Ministers must have foreign credibility, alongside the ability to form a cohesive support team. Socially a Prime Minster must not only recognize and promote popular ideas, but must also be relatable in part to the people. -

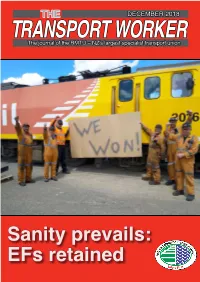

Sanity Prevails: Efs Retained 2 Contents Editorial ISSUE 4 • DECEMBER 2018

THE DECEMBER 2018 TRANSPORThe journal of the RMTU – NZ'sT largest WORKER specialist transport union Sanity prevails: EFs retained 2 CONTENTS EDITORIAL ISSUE 4 • DECEMBER 2018 12 SHANE JONES DOES HUTT SHOPS MP Shane Jones paid a visit to Hutt Workshops to familiarise himself with what the Work- shops can do and the affects of HPHE at the work face. 14 BIENNIAL CONFERENCE Wayne Butson General secretary RMTU Once again your Union held a very successful conference in Wellington with Plenty of positives a line-up of inspiring speakers. HIS time last year I wrote that rail, coastal shipping, public transport and regional development would see real gains during this Parliamentary term 36 MONGOLIAN MAGIC and that by late 2018 it would be a great time to be an RMTU member. Pare-Ana Bysterveld The good news is that by and large all has come to pass. (pictured) reports So it was with great joy that I was a member of the RMTU team to attend the Labour TParty Conference in Dunedin this year. That was its official name. However, we, and from the ICLS conference in a number of other parties, were calling it the Labour and RMTU Victory Conference. Mongolia where she Labour because, despite the nay-sayers, we remain with a viable coalition Gov- was blown away in ernment with partners working well together, and who, just one week prior, had more ways than one. announced a $35m funding of the rejuvenation of the North Island Main Trunk electric locomotives. When we launched the campaign to save the electric locos in 2016 I certainly did not fully appreciate the difficulty we would have in getting the victory and, secondly how we would pick up support from a wide range of community and environmental COVER PHOTOGRAPH: RMTU members of the groups, academics and other like-minded individuals. -

Perspectives on a Pacific Partnership

The United States and New Zealand: Perspectives on a Pacific Partnership Prepared by Bruce Robert Vaughn, PhD With funding from the sponsors of the Ian Axford (New Zealand) Fellowships in Public Policy August 2012 Established by the Level 8, 120 Featherston Street Telephone +64 4 472 2065 New Zealand government in 1995 PO Box 3465 Facsimile +64 4 499 5364 to facilitate public policy dialogue Wellington 6140 E-mail [email protected] between New Zealand and New Zealand www.fulbright.org.nz the United States of America © Bruce Robert Vaughn 2012 Published by Fulbright New Zealand, August 2012 The opinions and views expressed in this paper are the personal views of the author and do not represent in whole or part the opinions of Fulbright New Zealand or any New Zealand government agency. Nor do they represent the views of the Congressional Research Service or any US government agency. ISBN 978-1-877502-38-5 (print) ISBN 978-1-877502-39-2 (PDF) Ian Axford (New Zealand) Fellowships in Public Policy Established by the New Zealand Government in 1995 to reinforce links between New Zealand and the US, Ian Axford (New Zealand) Fellowships in Public Policy provide the opportunity for outstanding mid-career professionals from the United States of America to gain firsthand knowledge of public policy in New Zealand, including economic, social and political reforms and management of the government sector. The Ian Axford (New Zealand) Fellowships in Public Policy were named in honour of Sir Ian Axford, an eminent New Zealand astrophysicist and space scientist who served as patron of the fellowship programme until his death in March 2010. -

NEW ZEALAND POLITICAL STUDIES ASSOCIATION Conference CONFERENCE 2010 Programme

1 NEW ZEALAND POLITICAL STUDIES ASSOCIATION Conference CONFERENCE 2010 Programme Thursday 2 December 8.00 Registration Opens (Ground Floor, S Block) 9.15 Welcome Former Prime Minister and New Zealand Ambassador to the United States, and Chancellor of the University of Waikato, Jim Bolger (S.G.01) 9.30 Opening Address Bryan Gould The End of Politics (S.G.01) 10.30 Morning Tea Break 11.00 S.G.01 S.G.02 S.G.03 Roundtable: Engaging the Public in Current Issues in New Zealand Local Gender and Political Leadership the MMP Referendum Campaign Government Politics Convenor and Chair: Jennifer Curtin Convenor and Chair: Chris Rudd Convenor and Chair: Therese Jennifer Curtin Arseneau Jean Drage Women and Prime Ministerial What Will Auckland’s Reforms Mean for the Leadership: Beyond the Symbolic. MP Amy Adams Rest of Us? Ana Gilling Kate Stone Andy Asquith Gendered Conceptions of Power Managing the Metro Sector MP Rahui Katene Jane Christie Margie Comrie, Janine Hayward and Chris Maternal Legacies in Human Rights Sandra Grey Rudd Discourses as a Pathway to Political Media Coverage of the Local Body Elections Success: The Case of Michelle Bachelet and Cristina Fernández Laura Young E-Consultation and Local Government: Linda Trimble Creating Active Citizenship? When a Woman Topples a Man: Media Coverage of New Zealand Leadership ‘Coups’ 12.30 Lunch 1.00 S.G.01 S.G.02 S.G.03 S.1.01 Roundtable: Does the Roundtable: Marketing in The Politics of the Intangible Postgraduate Workshop: History of Political Thought Government: An Convenor and Chair: Peter -

Thrf-2019-1-Winners-V3.Pdf

TO ALL 21,100 Congratulations WINNERS Home Lottery #M13575 JohnDion Bilske Smith (#888888) JohnGeoff SmithDawes (#888888) You’ve(#105858) won a 2019 You’ve(#018199) won a 2019 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 KymJohn Tuck Smith (#121988) (#888888) JohnGraham Smith Harrison (#888888) JohnSheree Smith Horton (#888888) You’ve won the Grand Prize Home You’ve(#133706) won a 2019 You’ve(#044489) won a 2019 in Brighton and $1 Million Cash BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 GaryJohn PeacockSmith (#888888) (#119766) JohnBethany Smith Overall (#888888) JohnChristopher Smith (#888888)Rehn You’ve won a 2019 Porsche Cayenne, You’ve(#110522) won a 2019 You’ve(#132843) won a 2019 trip for 2 to Bora Bora and $250,000 Cash! BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 Holiday for Life #M13577 Cash Calendar #M13576 Richard Newson Simon Armstrong (#391397) Win(#556520) a You’ve won $200,000 in the Cash Calendar You’ve won 25 years of TICKETS Win big TICKETS holidayHolidays or $300,000 Cash STILL in$15,000 our in the Cash Cash Calendar 453321 Annette Papadulis; Dernancourt STILL every year AVAILABLE 383643 David Allan; Woodville Park 378834 Tania Seal; Wudinna AVAILABLE Calendar!373433 Graeme Blyth; Para Hills 428470 Vipul Sharma; Mawson Lakes for 25 years! 361598 Dianne Briske; Modbury Heights 307307 Peter Siatis; North Plympton 449940 Kate Brown; Hampton 409669 Victor Sigre; Henley Beach South 371447 Darryn Burdett; Hindmarsh Valley 414915 Cooper Stewart; Woodcroft 375191 Lynette Burrows; Glenelg North 450101 Filomena Tibaldi; Marden 398275 Stuart Davis; Hallett Cove 312911 Gaynor Trezona; Hallett Cove 418836 Deidre Mason; Noarlunga South 321163 Steven Vacca; Campbelltown 25 years of Holidays or $300,000 Cash $200,000 in the Cash Calendar Winner to be announced 29th March 2019 Winners to be announced 29th March 2019 Finding cures and improving care Date of Issue Home Lottery Licence #M13575 2729 FebruaryMarch 2019 2019 Cash Calendar Licence ##M13576M13576 in South Australia’s Hospitals. -

The Eagle 2013 the EAGLE

VOLUME 95 FOR MEMBERS OF ST JOHN’S COLLEGE The Eagle 2013 THE EAGLE Published in the United Kingdom in 2013 by St John’s College, Cambridge St John’s College Cambridge CB2 1TP johnian.joh.cam.ac.uk Telephone: 01223 338700 Fax: 01223 338727 Email: [email protected] Registered charity number 1137428 First published in the United Kingdom in 1858 by St John’s College, Cambridge Designed by Cameron Design (01284 725292, www.designcam.co.uk) Printed by Fisherprint (01733 341444, www.fisherprint.co.uk) Front cover: Divinity School by Ben Lister (www.benlister.com) The Eagle is published annually by St John’s College, Cambridge, and is sent free of charge to members of St John’s College and other interested parties. Page 2 www.joh.cam.ac.uk CONTENTS & MESSAGES CONTENTS & MESSAGES THE EAGLE Contents CONTENTS & MESSAGES Photography: John Kingsnorth Page 4 johnian.joh.cam.ac.uk Contents & messages THE EAGLE CONTENTS CONTENTS & MESSAGES Editorial..................................................................................................... 9 Message from the Master .......................................................................... 10 Articles Maggie Hartley: The best nursing job in the world ................................ 17 Esther-Miriam Wagner: Research at St John’s: A shared passion for learning......................................................................................... 20 Peter Leng: Living history .................................................................... 26 Frank Salmon: The conversion of Divinity