Workers' Ties

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter: Quarter 1, 2021

2021 TRANS-FORMTrans Pacific Union Newsletter 01, Jan-Mar Be a Transformer! On Easter weekend, I was sharing devotions for the youth camp that was held at Navesau Adventist High School in Fiji. What I saw really inspired me. These young people were not there just to have a good time, however were there to transform Navesau. They planted thousands of root crops, vegetables, painted railings and cleaned up the place. At the end of the camp, they donated many things for the school – from equipment for the computer lab, cooking utensils, fencing wire and even family household items. I am sure that it amounted to worth thousands of dollars. I literally saw our Vision Statement come alive. I saw ‘A Vibrant Adventist youth movement, living their hope in Jesus and transforming Navesau’. I know that there were many youth camps around the TPUM who also did similar things and I praise the Lord for the commitment our people have made to transform our Pacific. We can work together to transform our communities, and we can also do it individually. Jesus Christ illustrates this with this Parable in Matthew 13:33: “The kingdom of heaven is like yeast…mixed into…flour until it is worked all through the dough.” Jesus invites us to imagine the amazing properties of a little bit of yeast; it can make dough rise so that it bakes into wonderful bread. Like yeast, only a small expression of the kingdom of Jesus Christ in our lives can make an incredible impact on the lives and culture of people around us. -

Vanuatu Mission, Nambatu, Vila, Vanuatu

Vanuatu Mission, Nambatu, Vila, Vanuatu. Photo courtesy of Nos Terry. Vanuatu Mission BARRY OLIVER Barry Oliver, Ph.D., retired in 2015 as president of the South Pacific Division of Seventh-day Adventists, Sydney, Australia. An Australian by birth Oliver has served the Church as a pastor, evangelist, college teacher, and administrator. In retirement, he is a conjoint associate professor at Avondale College of Higher Education. He has authored over 106 significant publications and 192 magazine articles. He is married to Julie with three adult sons and three grandchildren. The Vanuatu Mission is a growing mission in the territory of the Trans-Pacific Union Mission of the South Pacific Division. Its headquarters are in Port Vila, Vanuatu. Before independence the mission was known as the New Hebrides Mission. The Territory and Statistics of the Vanuatu Mission The territory of the Vanuatu Mission is “Vanuatu.”1 It is a part of, and reports to the Trans Pacific Union Mission which is based in Tamavua, Suva, Fiji Islands. The Trans Pacific Union comprises the Seventh-day Adventist Church entities in the countries of American Samoa, Fiji, Kiribati, Nauru, Niue, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu, and Vanuatu. The administrative office of the Vanuatu Mission is located on Maine Street, Nambatu, Vila, Vanuatu. The postal address is P.O. Box 85, Vila Vanuatu.2 Its real and intellectual property is held in trust by the Seventh-day Adventist Church (Vanuatu) Limited, an incorporated entity based at the headquarters office of the Vanuatu Mission Vila, Vanuatu. The mission operates under General Conference and South Pacific Division (SPD) operating policies. -

2Nd Quarter 2016

MissionCHILDREN’S 2016 • QUARTER 2 • SOUTH PACIFIC DIVISION www.AdventistMission.org Contents On the Cover: Eleven-year-old Ngatia started a children’s Sabbath School under the trees. When the group couldn’t meet there anymore, God provided a very unusual meeting place. COOK ISLANDS FIJI 4 Life on the Island/ April 2 22 The Mystery of the Matches | June 4 24 Praying for Parents | June 11 SOLOMON ISLANDS 6 The Snooker Hut Girl| April 9 NEW ZEALAND 8 Giving the Invitation, Part 1 | April 16 26 Working With Jesus | June 18 10 Giving the Invitation, Part 2 | April 23 RESOURCES 12 The Children of Ngalitatae | April 30 28 Thirteenth Sabbath Program | June 25 PAPUA NEW GUINEA 30 Future Thirteenth Sabbath Projects 14 The Early Bird | May 7 31 Flags 16 Helping People | May 14 32 Recipes and Activities 18 Angels Are Real! | May 21 35 Resources/Masthead 20 The Unexpected Church | May 29 36 Map Your Offerings at Work The first quarter 2013, Thirteenth Sabbath Offering helped to build three Isolated Medical Outpost clinics in some of the most remote areas of Papua New Guiena, Vanuatu, and the Solomon Islands. These clinics provide the only easily accessible medical service to thousands of people living in these areas and offer a Seventh- day Adventist presence into these previously unentered areas. Thank you for your generosity! Above: The Buhalu Medical Clinic and staff house in Papua New Guiena were made possible in part through the Thirteenth Sabbath Offering. South Pacific Division ISSION ©2016 General Conference of M Seventh-day Adventists®• All rights reserved 12501 Old Columbia Pike, DVENTIST Silver Spring, MD 20904-6601 A 800.648.5824 • www.AdventistMission.org 2 Dear Sabbath School Leader, This quarter features the South Pacific and seashells. -

SEPTEMBER 2005 Cataloguing It

Oral history news Elayne retires from MOTAT Elayne Robertson worked with great NOHANZ enthusiasm at MOTAT in various Newsletter roles from 2001 to 2005. She found her metier in the Walsh Memorial Library and worked with the tenacity Volume 19, number 3 of a bloodhound researching the MOTAT photograph collection and SEPTEMBER 2005 cataloguing it. But really Elayne’s lasting achievement was the establishment EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE of the MOTAT Oral History section. In 2002 the new MOTAT Director, President: Jeremy Hubbard, took advice from Lesley Hall the existing staff and volunteers and approached Elayne. Executive Committee: Emma Dewson His faith was very well rewarded Linda Evans when Elayne immediately drew up Gillian Headifen equipment lists, plans, and budgets. Megan Hutching She recruited volunteers to carry out Alison Laurie interviews and brought all the Rachel Morley resources together, organised Rachael Selby training for us in interview Anne Thorpe techniques, machine operation and project planning. She was a model of Distance members of committee: how to do things and was unflagging Mary Donald (Auckland) in her energy which even extended Anna Green (Auckland) to assisting with organising the 2003 Marie Burgess (Gisborne) NOHANZ conference in Auckland. Ruth Greenaway (Christchurch) She and Ian gave many, many hours Jacqui Foley (Oamaru) of their weekends to the hard work Helen Frizzell (Dunedin) of copying and time coding, liaising with Alexander Turnbull Library and monitoring the output of the www.oralhistory.org.nz interviews as well as arranging and training staff. So it was with great sadness that we allowed Elayne to resign from the Newsletter: We seek news and Walsh Memorial Library and the Oral views from around the country about History Section. -

Singapore Campus a Coup for Massey

MasseyAuckland • Palmerston North • Wellington • Extramural News26 Haratua, May 2008 Issue 7 Rare kakariki take fl ight in new home Page 3 Future leader’s march with recent graduates during the procession following the ceremony to honour Mäori graduates. Graduation Palmerston North Writers’ Read in the capital Celebrating the collaboration with Singapore Polytechnic are, from left: Acting Vice-Chancellor Professor Ian Warrington, Principal of Singapore Polytechnic Page 6 Tan Hang Cheong, New Zealand High Commissioner to Singapore Martin Harvey, Senior Minister of State Lui and Dr Thomas Chai. On the table is a drink developed by Singapore Polytechnic and some Zespri gold and green kiwifruit. Singapore campus a coup for Massey A unique collaboration between Massey University and Education, Rear-Admiral Lui Tuck Yew, speaking at the Singapore Polytechnic will see the University’s fi rst offshore launch, said the collaboration was a strategic and timely campus developed. The venture, launched in Singapore last move given the value of the food and beverage industry in week, allows top polytechnic students to complete the fi nal Singapore reaching $SG17.6 billion ($NZ16.6 billion). two years of a Bachelor in Food Technology through Massey “Massey University’s Food Technology Institute is papers offered in Singapore. ranked among the top fi ve in the world,” Mr Yew said. “The To have the University’s food technology honours degree ministry has done a lot of groundwork and comparative selected from would-be providers all around the world is a studies before granting this degree tie-up and I am Graduation Wellington signifi cant achievement, Head of the Institute of Food Nutrition confi dent the programme will be of very high quality and and Palmerston North and Human Health Professor Richard Archer says. -

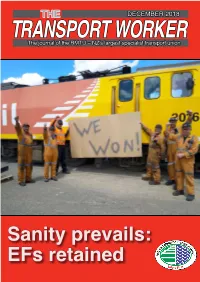

Sanity Prevails: Efs Retained 2 Contents Editorial ISSUE 4 • DECEMBER 2018

THE DECEMBER 2018 TRANSPORThe journal of the RMTU – NZ'sT largest WORKER specialist transport union Sanity prevails: EFs retained 2 CONTENTS EDITORIAL ISSUE 4 • DECEMBER 2018 12 SHANE JONES DOES HUTT SHOPS MP Shane Jones paid a visit to Hutt Workshops to familiarise himself with what the Work- shops can do and the affects of HPHE at the work face. 14 BIENNIAL CONFERENCE Wayne Butson General secretary RMTU Once again your Union held a very successful conference in Wellington with Plenty of positives a line-up of inspiring speakers. HIS time last year I wrote that rail, coastal shipping, public transport and regional development would see real gains during this Parliamentary term 36 MONGOLIAN MAGIC and that by late 2018 it would be a great time to be an RMTU member. Pare-Ana Bysterveld The good news is that by and large all has come to pass. (pictured) reports So it was with great joy that I was a member of the RMTU team to attend the Labour TParty Conference in Dunedin this year. That was its official name. However, we, and from the ICLS conference in a number of other parties, were calling it the Labour and RMTU Victory Conference. Mongolia where she Labour because, despite the nay-sayers, we remain with a viable coalition Gov- was blown away in ernment with partners working well together, and who, just one week prior, had more ways than one. announced a $35m funding of the rejuvenation of the North Island Main Trunk electric locomotives. When we launched the campaign to save the electric locos in 2016 I certainly did not fully appreciate the difficulty we would have in getting the victory and, secondly how we would pick up support from a wide range of community and environmental COVER PHOTOGRAPH: RMTU members of the groups, academics and other like-minded individuals. -

Register of Pecuniary and Other Specified Interests Summary 2017

J. 7 Register of Pecuniary and Other Specified Interests of Members of Parliament: Summary of annual returns as at 31 January 2017 Fifty-first Parliament Presented to the House of Representatives pursuant to Appendix B of the Standing Orders of the House of Representatives REGISTER OF PECUNIARY AND OTHER SPECIFIED INTERESTS OF MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT: SUMMARY OF ANNUAL RETURNS J. 7 2 REGISTER OF PECUNIARY AND OTHER SPECIFIED INTERESTS OF MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT: SUMMARY OF ANNUAL RETURNS J. 7 MISTER SPEAKER I have the honour to provide to you, pursuant to clause 18(3) of Appendix B of the Standing Orders of the House of Representatives, a copy of the summary booklet containing a fair and accurate description of the information contained in the Register of Pecuniary and Other Specified Interests of Members of Parliament, as at 31 January 2017. Sir Maarten Wevers KNZM Registrar of Pecuniary and Other Specified Interests of Members of Parliament 3 REGISTER OF PECUNIARY AND OTHER SPECIFIED INTERESTS OF MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT: SUMMARY OF ANNUAL RETURNS J. 7 Introduction Since 2005, members of Parliament have been required to make an annual return of their pecuniary and other specified personal interests, as set out in clauses 5 to 8 of Appendix B of the Standing Orders of the House of Representatives. The interests that are required to be registered are listed below. Items 1 to 9 provide a “snapshot” or stock of pecuniary and specified interests of members as at 31 January 2017. Items 10 to 13 identify a flow of members’ interests for the period from the member’s previous return. -

Māori and Aboriginal Women in the Public Eye

MĀORI AND ABORIGINAL WOMEN IN THE PUBLIC EYE REPRESENTING DIFFERENCE, 1950–2000 MĀORI AND ABORIGINAL WOMEN IN THE PUBLIC EYE REPRESENTING DIFFERENCE, 1950–2000 KAREN FOX THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Fox, Karen. Title: Māori and Aboriginal women in the public eye : representing difference, 1950-2000 / Karen Fox. ISBN: 9781921862618 (pbk.) 9781921862625 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Women, Māori--New Zealand--History. Women, Aboriginal Australian--Australia--History. Women, Māori--New Zealand--Social conditions. Women, Aboriginal Australian--Australia--Social conditions. Indigenous women--New Zealand--Public opinion. Indigenous women--Australia--Public opinion. Women in popular culture--New Zealand. Women in popular culture--Australia. Indigenous peoples in popular culture--New Zealand. Indigenous peoples in popular culture--Australia. Dewey Number: 305.4880099442 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover image: ‘Maori guide Rangi at Whakarewarewa, New Zealand, 1935’, PIC/8725/635 LOC Album 1056/D. National Library of Australia, Canberra. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2011 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Abbreviations . ix Illustrations . xi Glossary of Māori Words . xiii Note on Usage . xv Introduction . 1 Chapter One . -

Debate Recovery? Ch

JANUARY 16, 1976 25 CENTS VOLUME 40/NUMBER 2 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE actions nee - DEBATE U.S. LEFT GROUPS DISCUSS VITAL ISSUES IN REVOLUTION. PAGE 8. RECOVERY? MARXIST TELLS WHY ECONOMIC UPTURN HAS NOT BROUGHT JOBS. PAGE 24. RUSSELL MEANS CONVICTED IN S.D. FRAME-UP. PAGE 13. Original murder charges against Hurricane Carter stand exposed and discredited. Now New Jersey officials seek to keep him' behind bars on new frame-up as 'accomplice/ See page 7. PITTSBURGH STRIKERS FIGHT TO SAVE SCHOOLS. PAGE 14. CH ACTION TO HALT COP TERROR a Ira me- IN NATIONAL CITY. PAGE 17. In Brief NO MORE SHACKLES FOR SAN QUENTIN SIX: The lation that would deprive undocumented workers of their San Quentin Six have scored a victory with their civil suit rights. charging "cruel and unusual punishment" in their treat The group's "Action Letter" notes, "[These] bills are ment by prison authorities. In December a federal judge nothing but the focusing on our people and upon all Brown THIS ordered an end to the use of tear gas, neck chains, or any and Asian people's ability to obtain and keep a job, get a mechanical restraints except handcuffs "unless there is an promotion, and to be able to fight off discrimination. But imminent threat of bodily harm" for the six Black and now it will not only be the government agencies that will be WEEK'S Latino prisoners. The judge also expanded the outdoor qualifying Brown people as to whether we have the 'right' to periods allowed all prisoners in the "maximum security" be here, but every employer will be challenging us at every MILITANT Adjustment Center at San Quentin. -

Thrf-2019-1-Winners-V3.Pdf

TO ALL 21,100 Congratulations WINNERS Home Lottery #M13575 JohnDion Bilske Smith (#888888) JohnGeoff SmithDawes (#888888) You’ve(#105858) won a 2019 You’ve(#018199) won a 2019 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 KymJohn Tuck Smith (#121988) (#888888) JohnGraham Smith Harrison (#888888) JohnSheree Smith Horton (#888888) You’ve won the Grand Prize Home You’ve(#133706) won a 2019 You’ve(#044489) won a 2019 in Brighton and $1 Million Cash BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 GaryJohn PeacockSmith (#888888) (#119766) JohnBethany Smith Overall (#888888) JohnChristopher Smith (#888888)Rehn You’ve won a 2019 Porsche Cayenne, You’ve(#110522) won a 2019 You’ve(#132843) won a 2019 trip for 2 to Bora Bora and $250,000 Cash! BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 Holiday for Life #M13577 Cash Calendar #M13576 Richard Newson Simon Armstrong (#391397) Win(#556520) a You’ve won $200,000 in the Cash Calendar You’ve won 25 years of TICKETS Win big TICKETS holidayHolidays or $300,000 Cash STILL in$15,000 our in the Cash Cash Calendar 453321 Annette Papadulis; Dernancourt STILL every year AVAILABLE 383643 David Allan; Woodville Park 378834 Tania Seal; Wudinna AVAILABLE Calendar!373433 Graeme Blyth; Para Hills 428470 Vipul Sharma; Mawson Lakes for 25 years! 361598 Dianne Briske; Modbury Heights 307307 Peter Siatis; North Plympton 449940 Kate Brown; Hampton 409669 Victor Sigre; Henley Beach South 371447 Darryn Burdett; Hindmarsh Valley 414915 Cooper Stewart; Woodcroft 375191 Lynette Burrows; Glenelg North 450101 Filomena Tibaldi; Marden 398275 Stuart Davis; Hallett Cove 312911 Gaynor Trezona; Hallett Cove 418836 Deidre Mason; Noarlunga South 321163 Steven Vacca; Campbelltown 25 years of Holidays or $300,000 Cash $200,000 in the Cash Calendar Winner to be announced 29th March 2019 Winners to be announced 29th March 2019 Finding cures and improving care Date of Issue Home Lottery Licence #M13575 2729 FebruaryMarch 2019 2019 Cash Calendar Licence ##M13576M13576 in South Australia’s Hospitals. -

The Eagle 2013 the EAGLE

VOLUME 95 FOR MEMBERS OF ST JOHN’S COLLEGE The Eagle 2013 THE EAGLE Published in the United Kingdom in 2013 by St John’s College, Cambridge St John’s College Cambridge CB2 1TP johnian.joh.cam.ac.uk Telephone: 01223 338700 Fax: 01223 338727 Email: [email protected] Registered charity number 1137428 First published in the United Kingdom in 1858 by St John’s College, Cambridge Designed by Cameron Design (01284 725292, www.designcam.co.uk) Printed by Fisherprint (01733 341444, www.fisherprint.co.uk) Front cover: Divinity School by Ben Lister (www.benlister.com) The Eagle is published annually by St John’s College, Cambridge, and is sent free of charge to members of St John’s College and other interested parties. Page 2 www.joh.cam.ac.uk CONTENTS & MESSAGES CONTENTS & MESSAGES THE EAGLE Contents CONTENTS & MESSAGES Photography: John Kingsnorth Page 4 johnian.joh.cam.ac.uk Contents & messages THE EAGLE CONTENTS CONTENTS & MESSAGES Editorial..................................................................................................... 9 Message from the Master .......................................................................... 10 Articles Maggie Hartley: The best nursing job in the world ................................ 17 Esther-Miriam Wagner: Research at St John’s: A shared passion for learning......................................................................................... 20 Peter Leng: Living history .................................................................... 26 Frank Salmon: The conversion of Divinity -

Life Stories of Robert Semple

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. From Coal Pit to Leather Pit: Life Stories of Robert Semple A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of a PhD in History at Massey University Carina Hickey 2010 ii Abstract In the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography Len Richardson described Robert Semple as one of the most colourful leaders of the New Zealand labour movement in the first half of the twentieth century. Semple was a national figure in his time and, although historians had outlined some aspects of his public career, there has been no full-length biography written on him. In New Zealand history his characterisation is dominated by two public personas. Firstly, he is remembered as the radical organiser for the New Zealand Federation of Labour (colloquially known as the Red Feds), during 1910-1913. Semple’s second image is as the flamboyant Minister of Public Works in the first New Zealand Labour government from 1935-49. This thesis is not organised in a chronological structure as may be expected of a biography but is centred on a series of themes which have appeared most prominently and which reflect the patterns most prevalent in Semple’s life. The themes were based on activities which were of perceived value to Semple. Thus, the thematic selection was a complex interaction between an author’s role shaping and forming Semple’s life and perceived real patterns visible in the sources.