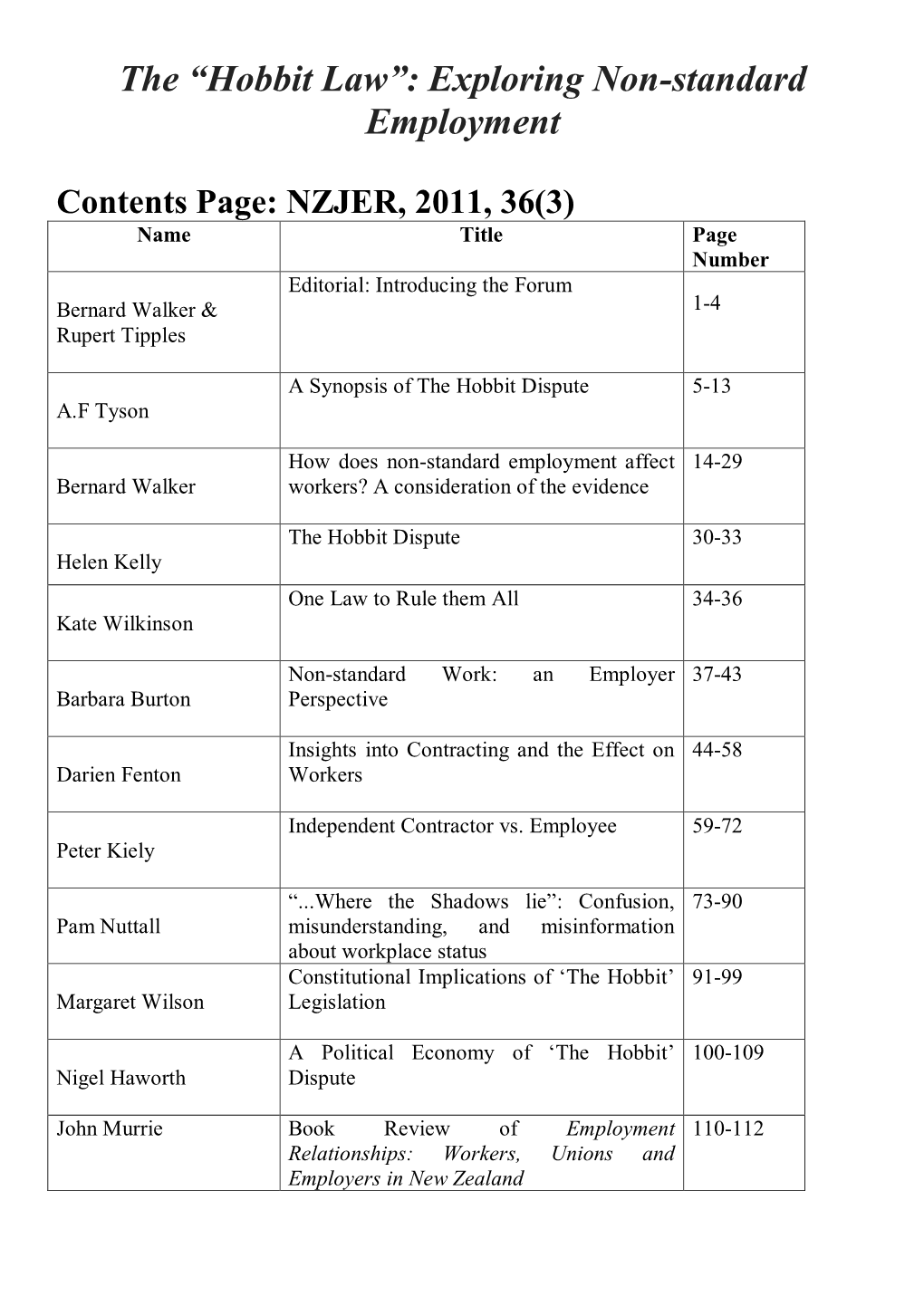

Hobbit Law”: Exploring Non-Standard Employment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

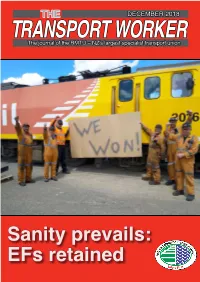

Sanity Prevails: Efs Retained 2 Contents Editorial ISSUE 4 • DECEMBER 2018

THE DECEMBER 2018 TRANSPORThe journal of the RMTU – NZ'sT largest WORKER specialist transport union Sanity prevails: EFs retained 2 CONTENTS EDITORIAL ISSUE 4 • DECEMBER 2018 12 SHANE JONES DOES HUTT SHOPS MP Shane Jones paid a visit to Hutt Workshops to familiarise himself with what the Work- shops can do and the affects of HPHE at the work face. 14 BIENNIAL CONFERENCE Wayne Butson General secretary RMTU Once again your Union held a very successful conference in Wellington with Plenty of positives a line-up of inspiring speakers. HIS time last year I wrote that rail, coastal shipping, public transport and regional development would see real gains during this Parliamentary term 36 MONGOLIAN MAGIC and that by late 2018 it would be a great time to be an RMTU member. Pare-Ana Bysterveld The good news is that by and large all has come to pass. (pictured) reports So it was with great joy that I was a member of the RMTU team to attend the Labour TParty Conference in Dunedin this year. That was its official name. However, we, and from the ICLS conference in a number of other parties, were calling it the Labour and RMTU Victory Conference. Mongolia where she Labour because, despite the nay-sayers, we remain with a viable coalition Gov- was blown away in ernment with partners working well together, and who, just one week prior, had more ways than one. announced a $35m funding of the rejuvenation of the North Island Main Trunk electric locomotives. When we launched the campaign to save the electric locos in 2016 I certainly did not fully appreciate the difficulty we would have in getting the victory and, secondly how we would pick up support from a wide range of community and environmental COVER PHOTOGRAPH: RMTU members of the groups, academics and other like-minded individuals. -

Thrf-2019-1-Winners-V3.Pdf

TO ALL 21,100 Congratulations WINNERS Home Lottery #M13575 JohnDion Bilske Smith (#888888) JohnGeoff SmithDawes (#888888) You’ve(#105858) won a 2019 You’ve(#018199) won a 2019 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 KymJohn Tuck Smith (#121988) (#888888) JohnGraham Smith Harrison (#888888) JohnSheree Smith Horton (#888888) You’ve won the Grand Prize Home You’ve(#133706) won a 2019 You’ve(#044489) won a 2019 in Brighton and $1 Million Cash BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 GaryJohn PeacockSmith (#888888) (#119766) JohnBethany Smith Overall (#888888) JohnChristopher Smith (#888888)Rehn You’ve won a 2019 Porsche Cayenne, You’ve(#110522) won a 2019 You’ve(#132843) won a 2019 trip for 2 to Bora Bora and $250,000 Cash! BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 Holiday for Life #M13577 Cash Calendar #M13576 Richard Newson Simon Armstrong (#391397) Win(#556520) a You’ve won $200,000 in the Cash Calendar You’ve won 25 years of TICKETS Win big TICKETS holidayHolidays or $300,000 Cash STILL in$15,000 our in the Cash Cash Calendar 453321 Annette Papadulis; Dernancourt STILL every year AVAILABLE 383643 David Allan; Woodville Park 378834 Tania Seal; Wudinna AVAILABLE Calendar!373433 Graeme Blyth; Para Hills 428470 Vipul Sharma; Mawson Lakes for 25 years! 361598 Dianne Briske; Modbury Heights 307307 Peter Siatis; North Plympton 449940 Kate Brown; Hampton 409669 Victor Sigre; Henley Beach South 371447 Darryn Burdett; Hindmarsh Valley 414915 Cooper Stewart; Woodcroft 375191 Lynette Burrows; Glenelg North 450101 Filomena Tibaldi; Marden 398275 Stuart Davis; Hallett Cove 312911 Gaynor Trezona; Hallett Cove 418836 Deidre Mason; Noarlunga South 321163 Steven Vacca; Campbelltown 25 years of Holidays or $300,000 Cash $200,000 in the Cash Calendar Winner to be announced 29th March 2019 Winners to be announced 29th March 2019 Finding cures and improving care Date of Issue Home Lottery Licence #M13575 2729 FebruaryMarch 2019 2019 Cash Calendar Licence ##M13576M13576 in South Australia’s Hospitals. -

The Eagle 2013 the EAGLE

VOLUME 95 FOR MEMBERS OF ST JOHN’S COLLEGE The Eagle 2013 THE EAGLE Published in the United Kingdom in 2013 by St John’s College, Cambridge St John’s College Cambridge CB2 1TP johnian.joh.cam.ac.uk Telephone: 01223 338700 Fax: 01223 338727 Email: [email protected] Registered charity number 1137428 First published in the United Kingdom in 1858 by St John’s College, Cambridge Designed by Cameron Design (01284 725292, www.designcam.co.uk) Printed by Fisherprint (01733 341444, www.fisherprint.co.uk) Front cover: Divinity School by Ben Lister (www.benlister.com) The Eagle is published annually by St John’s College, Cambridge, and is sent free of charge to members of St John’s College and other interested parties. Page 2 www.joh.cam.ac.uk CONTENTS & MESSAGES CONTENTS & MESSAGES THE EAGLE Contents CONTENTS & MESSAGES Photography: John Kingsnorth Page 4 johnian.joh.cam.ac.uk Contents & messages THE EAGLE CONTENTS CONTENTS & MESSAGES Editorial..................................................................................................... 9 Message from the Master .......................................................................... 10 Articles Maggie Hartley: The best nursing job in the world ................................ 17 Esther-Miriam Wagner: Research at St John’s: A shared passion for learning......................................................................................... 20 Peter Leng: Living history .................................................................... 26 Frank Salmon: The conversion of Divinity -

Professor Richard Epstein and the New Zealand Employment Contract

Wailes: Professor Richard Epstein and the New Zealand Employment Contract PROFESSOR RICHARD EPSTEIN AND THE NEW ZEALAND EMPLOYMENT CONTRACTS ACT: A CRITIQUE NICK WAILES* Penelope Brook, one of the major proponents of radical reform in the New Zealand labor law system, has characterized the New Zealand Em- ployment Contracts Act (ECA) as an "incomplete revolution."' She argues that this "incompleteness" stems from the retention of a specialist labor law jurisdiction and the failure to frame the Act around the principle of contract at will.2 The emphasis placed on these two issues-specialist jurisdiction and contract at will-demonstrates the influence arguments made by Chi- cago Law Professor, Richard Epstein, have played on labor law reform in New Zealand. Despite reservations about its final form, Brook gives her support to the ECA, precisely because it operationalizes some of Epstein's ideas. It has been generally acknowledged that ideas like those of Epstein played a significant role in the introduction of the ECA in New Zealand. However, while critics of the ECA have acknowledged the importance of Epstein's ideas in the debate which led up to the passing of the Act, few at- tempts have been made to outline clearly or critique Epstein's views. This Paper attempts to fill this lacuna by providing a critique of the behavioral assumptions that Epstein brings to his analysis of labor law. The first sec- * The Department of Industrial Relations, The University of Sydney, Australia. This is an amended version of Nick Wailes, The Case Against Specialist Jurisdictionfor Labor Law: PhilosophicalAssumptions of a Common Law for Labor Relations, 19 N.Z.J. -

Parliamentary Scrutiny of Human Rights in New Zealand (Report)

PARLIAMENTARY SCRUTINY OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN NEW ZEALAND: GLASS HALF FULL? Prof. Judy McGregor and Prof. Margaret Wilson AUT UNIVERSITY | UNIVERSITY OF WAIKATO RESEARCH FUNDED BY THE NEW ZEALAND LAW FOUNDATION Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 2 Recent Scholarship ..................................................................................................................... 3 Methodology ............................................................................................................................ 22 Select committee controversy ................................................................................................. 28 Rights-infringing legislation. .................................................................................................... 32 Criminal Records (Expungement of Convictions for Historical Homosexual Offences) Bill. ... 45 Domestic Violence-Victims’ Protection Bill ............................................................................. 60 The Electoral (Integrity) Amendment Bill ................................................................................ 75 Parliamentary scrutiny of human rights in New Zealand: Summary report. .......................... 89 1 Introduction This research is a focused project on one aspect of the parliamentary process. It provides a contextualised account of select committees and their scrutiny of human rights with a particular -

CESCR, NZ LOIPR, Peace Movement Aotearoa, February 2016

Peace Movement Aotearoa PO Box 9314, Wellington 6141, Aotearoa New Zealand. Tel +64 4 382 8129 Email [email protected] Web site www.converge.org.nz/pma ______________________________________________________________________________ NGO information for the 57th session of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, February 2016 List of Issues Prior to Reporting: New Zealand Overview 1. This preliminary report provides an outline of some issues of concern with regard to the state party's compliance with the provisions of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR, the Covenant). Its purpose is to assist the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (the Committee) with its preparation of the List of Issues Prior to Reporting (LOIPR) in advance of New Zealand's Fourth Periodic Report (the Periodic Report). 2. There are five main sections below: A. Information on Peace Movement Aotearoa B. Constitutional and legal framework C. Indigenous Peoples’ Rights (Articles 1, 2 and 15) i) Overview, ii) Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement, and iii) Impact of the activities of New Zealand companies on indigenous communities overseas. D. Socio-economic conditions (Articles 2, 3, 7, 9 11, and others) i) Increasing levels of child poverty, ii) Right to an adequate standard of living: social welfare / paid employment, iii) Housing crisis, iv) Allocation of public spending E. The Optional Protocol to the Covenant 3. More detailed information will be provided on these and other issues in parallel reports from Peace Movement Aotearoa and other NGOs following the state party’s submission of the Periodic Report next year. Due to time constraints, we have not covered as many issues in this report as we would have liked to, and we therefore refer the Committee to the Human Rights Foundation’s report which covers a range of concerns that we share. -

Do We Need Kiwi Lessons in Biculturalism?

Do We Need Kiwi Lessons in Biculturalism? Considering the Usefulness of Aotearoa/New Zealand’sPakehā ̄Identity in Re-Articulating Indigenous Settler Relations in Canada DAVID B. MACDONALD University of Guelph Narratives of “métissage” (Saul, 2008), “settler” (Regan, 2010; Barker and Lowman, 2014) “treaty people” (Epp, 2008; Erasmus, 2011) and now a focus on completing the “unfinished business of Confederation” (Roman, 2015) reinforce the view that the government is embarking on a new polit- ical project of Indigenous recognition, inclusion and partnership. Yet recon- ciliation is a contested concept, especially since we are only now dealing with the inter-generational and traumatic legacies of the Indian residential schools, missing and murdered Indigenous women and a long history of (at least) cultural genocide. Further, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, with its focus on Indigenous self-determi- nation, has yet to be implemented in Canadian law. Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) presented over 94 recommendations and sub-recommendations to consider, outlining a long-term process of cre- ating positive relationships and helping to restore the lands, languages, David MacDonald, Department of Political Science, University of Guelph, 50 Stone Road East, Guelph ON, N1G 2W1, email: [email protected] Nga mihi nui, nya: weh,̨ kinana’skomitina’wa’w, miigwech, thank you, to Dana Wensley, Rick Hill, Paulette Regan, Dawnis Kennedy, Malissa Bryan, Sheryl Lightfoot, Kiera Ladner, Pat Case, Malinda Smith, Brian Budd, Moana Jackson, Margaret Mutu, Paul Spoonley, Stephen May, Robert Joseph, Dame Claudia Orange, Chris Finlayson, Makere Stewart Harawira, Hone Harawira, Te Ururoa Flavell, Tā Pita Sharples, Joris De Bres, Sir Anand Satyananand, Phil Goff, Shane Jones, Ashraf Choudhary, Andrew Butcher, Hekia Parata, Judith Collins, Kanwaljit Bakshi, Chris Laidlaw, Rajen Prasad, Graham White, and three anonymous reviewers. -

GLOBALISATION, SOVEREIGNTY and the TRANSFORMATION of NEW ZEALAND FOREIGN POLICY Robert G

Working Pape Working GLOBALISATION, SOVEREIGNTY AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF NEW ZEALAND FOREIGN POLICY Robert G. Patman Centre for Strategic Studies: New Zealand r Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. No.21/05 CENTRE FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES NEW ZEALAND Working Papers The Centre for Strategic Studies Working Paper series is designed to give a forum for scholars and specialists working on issues related directly to New Zealand’s security, broadly defined, and to the Asia-Pacific region. The Working Papers represent ‘work in progress’ and as such may be altered and expanded after feedback before being published elsewhere. The opinions expressed and conclusions drawn in the Working Papers are solely those of the writer. They do not necessarily represent the views of the Centre for Strategic Studies or any other organisation with which the writer may be affiliated. For further information or additional copies of the Working Papers please contact: Centre for Strategic Studies: New Zealand Victoria University of Wellington PO Box 600 Wellington New Zealand. Tel: 64 4 463 5434 Fax: 64 4 463 5737 Email: [email protected] Website: www.vuw.ac.nz/css/ Centre for Strategic Studies Victoria University of Wellington 2005 © Robert G. Patman ISSN 1175-1339 Desktop Design: Synonne Rajanayagam Globalisation, Sovereignty, and the Transformation of New Zealand Foreign Policy Working Paper 21/05 Abstract Structural changes in the global system have raised a big question mark over a traditional working principle of international relations, namely, state sovereignty. With the end of the Cold War and the subsequent break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991, the US has been left as the world’s only superpower. -

POLITICAL COMMENTARY Reflection on the 2014 Election: Implications for Women

88 POLITICAL COMMENTARY Reflection on the 2014 election: Implications for women SUE BRADFORD This has not been a good election for women, unless perhaps you’re white, wealthy and suf- ficiently lacking in empathy to believe that John Key and his mates are going to do a good job for us all over the next three years. Whether considering the gender makeup of Parliament and Cabinet, the likely consequences of a National government for women and children over the next few years, or the melancholy fate of the parties of the left, the aspiration of pre-election initiatives like the Women’s Election Agenda appear somewhat dimmed by reality. Parliament A noticeable feature of the 51st Parliament is the reduced number of women elected, down to 37 out of 84, meaning that women make up slightly under 32% of MPs. The 2011 Parliament had 39 women MPs. High hopes that the maturation of MMP and the legacy of the Helen Clark era would mean a steady increase in the numbers of women entering Parliament have clearly not been met. Apart from the Greens, it is hard to identify much success among the major political parties in achieving greater gender balance among their elected representatives. Just 34% of Labour’s MPs are women (11 out of 32), meaning that their goal of reaching 45% women MPs by this election has fallen sadly short. Turning to the makeup of the power holders in National’s third term Cabinet, a pitiful six out of 20 full Ministers are women, with the highest ranked being Paula Bennett at number five. -

Trans Tasman Politics, Legislation, Trade, Economy Now in Its 50Th Year 22 March Issue • 2018 No

www.transtasman.co.nz Trans Tasman Politics, Legislation, Trade, Economy Now in its 50th year 22 March Issue • 2018 No. 18/2115 ISSN 2324-2930 Comment Tough Week For Ardern If Jacinda Ardern is in the habit of asking herself whether she’s doing a good job at the end of each week, she’ll have had the first one when the answer has probably been no. It has been a week in which she has looked less like a leader than she has at any time so far in her time as head of the Labour Party and then Prime Minister. Jacindamania is fading. The tough reality of weekly politics is taking over. The Party apparatus has dropped her in it – but she seems powerless to get rid of the source of the problem, because while she is Prime Minister, she’s not in charge of the party. The party seems to have asserted its rights to do things its own way, even if this means keeping the PM in the dark about a sex assault claim after an alleged incident at a party function. Even a Cabinet Minister knew and didn’t tell her. This made Ardern look powerless. Her coalition partner, Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Winston Peters also led her a merry dance this week over the Russia Free Trade agreement the two parties agreed to pursue as part of their coalition agree- ment. Peters unfortunately chose a week in which Russia was accused of a deadly nerve agent attack on one of its former spies in Britain to up the ante on pushing the FTA forward. -

February 2018 END-OF-LIFE CHOICE SOCIETY of NEW ZEALAND INC Issue 49 Member of the World Federation of Right to Die Societies

February 2018 END-OF-LIFE CHOICE SOCIETY OF NEW ZEALAND INC Issue 49 Member of the World Federation of Right to Die Societies EDITORIAL - 2018 IS MAKE OR BREAK YEAR We have entered a critical new year for the cause we conservatives - are in a minority but they are bent on have been fighting four decades so far. fighting a campaign blatantly built on lies and Whether it will prove to be a happy one remains misinformation to stop us and overseas experience to be seen. shows they are funded by wealthy church coffers. For while we made history in December when We expect a better deal from Parliament's Parliament voted for the first time to allow an assisted Justice Select Committee than we received from the dying Bill to progress beyond the first stage, we can biased group that last considered the issue, but we have no doubts about the struggle ahead to win the have only until February 20 to make formal ultimate human right of the 21st century. submissions and we need all our members to make It has never been more important for every their voices heard. member of our society to do whatever they can to The committee then has until mid-September promote the right to die with dignity and persuade our to make its recommendations to Parliament before all politicians to go on and pass an enlightened law. MPs vote again on whether New Zealand will join 110 This is a make or break year. It has been 15 million Americans and millions more in Canada, years since Parliament last tackled the issue and if we Europe, South America and Australia with the right to miss out on this opportunity there will be another long allow our terminally ill who are suffering intolerably to gap before it faces it again. -

Publ 408/Pols 436 State and the Economy – Globalisation Issues

School of Government PUBL 408/POLS 436 STATE AND THE ECONOMY – GLOBALISATION ISSUES Trimester 1 2007 COURSE OUTLINE Contact Details Course Co-ordinator: Dr John Wilson RH 212 Tel: 04 463 5082 [email protected] [email protected] Office hours: Wednesday 1.00pm – 2.30pm; other times by appointment. Administrator: Francine McGee RH 821 (Reception) 04 463 – 6599 [email protected] Class Times and Room Numbers Lectures: Wednesday 2.40pm – 4.30pm GB117 Additional information will be posted on the departmental notice board, or announced in class. Course aims and objectives The state and the market represent two different approaches to organising human behaviour, and the relationship between them has always affected the conduct of public policy. A key theme of the course is the way in which states manage their economic development within an international context increasingly characterised by patterns of globalisation. While globalisation may enhance a nation’s economic prosperity, it also has implications for the ability of national governments to autonomously pursue economic, social, and environmental objectives. Case studies examine how the pursuit of economic development goals can conflict with wider policy objectives in the energy, environmental, trade, and social policy areas. 1 By the end of the course, students should be able to: appreciate the evolution of the state- economy relationship: understand the role of government in managing the economy; understand and critique the challenges posed by globalisation to national and economic development; show to what extent states can autonomously pursue their public policy goals in the era of globalisation.