CESCR, NZ LOIPR, Peace Movement Aotearoa, February 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where Are the Audiences?

WHERE ARE THE AUDIENCES? Full Report Introduction • New Zealand On Air (NZ On Air) supports and funds audio and visual public media content for New Zealand audiences. It does so through the platform neutral NZ Media Fund which has four streams; scripted, factual, music, and platforms. • Given the platform neutrality of this fund and the need to efficiently and effectively reach both mass and targeted audiences, it is essential NZ On Air have an accurate understanding of the current and evolving behaviour of NZ audiences. • To this end NZ On Air conduct the research study Where Are The Audiences? every two years. The 2014 benchmark study established a point in time view of audience behaviour. The 2016 study identified how audience behaviour had shifted over time. • This document presents the findings of the 2018 study and documents how far the trends revealed in 2016 have moved and identify any new trends evident in NZ audience behaviour. • Since the 2016 study the media environment has continued to evolve. Key changes include: − Ongoing PUTs declines − Anecdotally at least, falling SKY TV subscription and growth of NZ based SVOD services − New TV channels (eg. Bravo, HGTV, Viceland, Jones! Too) and the closure of others (eg. FOUR, TVNZ Kidzone, The Zone) • The 2018 Where Are The Audiences? study aims to hold a mirror up to New Zealand and its people and: − Inform NZ On Air’s content and platform strategy as well as specific content proposals − Continue to position NZ On Air as a thought and knowledge leader with stakeholders including Government, broadcasters and platform owners, content producers, and journalists. -

Choice-Living-Jan-Feb-20

Jan/Feb 2020 Living Choice residents, Robert and Glenda Bretton with their beloved pooch, Buddy. You can see their home on pages 14 & 15. www.livingchoice.com.au The choice of luxury and the luxury of choice SET TO GROW IN 2020 Living Choice is poised to expand this year with a the human services sector specialising number of approvals pending for new villages and in aged care, disability, community further expansion at Living Choice Glenhaven. To development and social planning streamline operations, three key current staff members within large scale, high volume public have been promoted, including Jason Sack who has been and private sector organisations for appointed Group General Manager, Gail Eyres who over 30 years. is now Regional Manager for our Sydney and Central Kylie, together with her husband and two Coast villages and Tracy Blair who has been promoted daughters, lives on a farm at Mangrove Mountain to Regional Manager of our Sunshine Coast villages. on the Central Coast where they breed cattle and horses. in addition, Kylie Johnson has recently been appointed The Living Choice Design Team: Michael Alexander, Jason Morato, Teresa Agravante, Pictured top right: Jason Sack, previously GM Sydney & Azadeh Shahvarpour, Aaron Wong, Andrew Hii and Pedram Abbasi. Living Choice’s Home Care Operations Manager and Adelaide, is now the Group General Manager. she is brimming with ideas to grow the Home Care division and improve services for residents. Kylie is well- Pictured bottom right: Kylie Johnson, Living Choice’s new equipped for the role, having professionally served in Home Care Operations Manager. -

2019 Winners & Finalists

2019 WINNERS & FINALISTS Associated Craft Award Winner Alison Watt The Radio Bureau Finalists MediaWorks Trade Marketing Team MediaWorks MediaWorks Radio Integration Team MediaWorks Best Community Campaign Winner Dena Roberts, Dominic Harvey, Tom McKenzie, Bex Dewhurst, Ryan Rathbone, Lucy 5 Marathons in 5 Days The Edge Network Carthew, Lucy Hills, Clinton Randell, Megan Annear, Ricky Bannister Finalists Leanne Hutchinson, Jason Gunn, Jay-Jay Feeney, Todd Fisher, Matt Anderson, Shae Jingle Bail More FM Network Osborne, Abby Quinn, Mel Low, Talia Purser Petition for Pride Mel Toomey, Casey Sullivan, Daniel Mac The Edge Wellington Best Content Best Content Director Winner Ryan Rathbone The Edge Network Finalists Ross Flahive ZM Network Christian Boston More FM Network Best Creative Feature Winner Whostalk ZB Phil Guyan, Josh Couch, Grace Bucknell, Phil Yule, Mike Hosking, Daryl Habraken Newstalk ZB Network / CBA Finalists Tarore John Cowan, Josh Couch, Rangi Kipa, Phil Yule Newstalk ZB Network / CBA Poo Towns of New Zealand Jeremy Pickford, Duncan Heyde, Thane Kirby, Jack Honeybone, Roisin Kelly The Rock Network Best Podcast Winner Gone Fishing Adam Dudding, Amy Maas, Tim Watkin, Justin Gregory, Rangi Powick, Jason Dorday RNZ National / Stuff Finalists Black Sheep William Ray, Tim Watkin RNZ National BANG! Melody Thomas, Tim Watkin RNZ National Best Show Producer - Music Show Winner Jeremy Pickford The Rock Drive with Thane & Dunc The Rock Network Finalists Alexandra Mullin The Edge Breakfast with Dom, Meg & Randell The Edge Network Ryan -

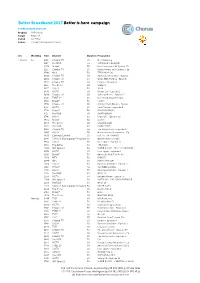

BB2017 Media Overview for Rsps

Better Broadband 2017 Better is here campaign TV PRE AIRDATE SPOTLIST Product All Products Target All 25-54 Period wc 7 May Source TVmap/The Nielsen Company w/c WeekDay Time Channel Duration Programme 7 May 17 Su 1112 Choice TV 30 No Advertising 7 May 17 Su 1217 the BOX 60 SURVIVOR: CAGAYAN 7 May 17 Su 1220 Bravo* 30 Real Housewives Of Sydney, Th 7 May 17 Su 1225 Choice TV 30 Better Homes and Gardens - Ep 7 May 17 Su 1340 MTV 30 TEEN MOM OG 7 May 17 Su 1410 Choice TV 30 American Restoration - Episod 7 May 17 Su 1454 Choice TV 60 Walks With My Dog - Episode 7 May 17 Su 1542 Choice TV 60 Empire - Episode 4 7 May 17 Su 1615 The Zone 60 SLIDERS 7 May 17 Su 1617 HGTV 30 16:00 7 May 17 Su 1640 HGTV 60 Hawaii Life - Episode 2 7 May 17 Su 1650 Choice TV 60 Jamie at Home - Episode 5 7 May 17 Su 1710 TVNZ 2* 60 Home and Away Omnibus 7 May 17 Su 1710 Bravo* 30 Catfish 7 May 17 Su 1710 Choice TV 30 Jimmy's Farm Diaries - Episod 7 May 17 Su 1717 HGTV 30 Yard Crashers - Episode 8 7 May 17 Su 1720 Prime* 30 RUGBY NATION 7 May 17 Su 1727 the BOX 30 SMACKDOWN 7 May 17 Su 1746 HGTV 60 Island Life - Episode 10 7 May 17 Su 1820 Bravo* 30 Catfish 7 May 17 Su 1854 The Zone 60 WIZARD WARS 7 May 17 Su 1905 the BOX 30 MAIN EVENT 7 May 17 Su 1906 Choice TV 60 The Living Room - Episode 37 7 May 17 Su 1906 HGTV 30 House Hunters Renovation - Ep 7 May 17 Su 1930 Comedy Central 30 LIVE AT THE APOLLO 7 May 17 Su 1945 Crime & Investigation Network 30 DEATH ROW STORIES 7 May 17 Su 1954 HGTV 30 Fixer Upper - Episode 6 7 May 17 Su 1955 The Zone 60 THE CAPE 7 May 17 Su 2000 -

Channel Lineup January 2018

MyTV CHANNEL LINEUP JANUARY 2018 ON ON ON SD HD• DEMAND SD HD• DEMAND SD HD• DEMAND My64 (WSTR) Cincinnati 11 511 Foundation Pack Kids & Family Music Choice 300-349• 4 • 4 A&E 36 536 4 Music Choice Play 577 Boomerang 284 4 ABC (WCPO) Cincinnati 9 509 4 National Geographic 43 543 4 Cartoon Network 46 546 • 4 Big Ten Network 206 606 NBC (WLWT) Cincinnati 5 505 4 Discovery Family 48 548 4 Beauty iQ 637 Newsy 508 Disney 49 549 • 4 Big Ten Overflow Network 207 NKU 818+ Disney Jr. 50 550 + • 4 Boone County 831 PBS Dayton/Community Access 16 Disney XD 282 682 • 4 Bounce TV 258 QVC 15 515 Nickelodeon 45 545 • 4 Campbell County 805-807, 810-812+ QVC2 244• Nick Jr. 286 686 4 • CBS (WKRC) Cincinnati 12 512 SonLife 265• Nicktoons 285 • 4 Cincinnati 800-804, 860 Sundance TV 227• 627 Teen Nick 287 • 4 COZI TV 290 TBNK 815-817, 819-821+ TV Land 35 535 • 4 C-Span 21 The CW 17 517 Universal Kids 283 C-Span 2 22 The Lebanon Channel/WKET2 6 Movies & Series DayStar 262• The Word Network 263• 4 Discovery Channel 32 532 THIS TV 259• MGM HD 628 ESPN 28 528 4 TLC 57 557 4 STARZEncore 482 4 ESPN2 29 529 Travel Channel 59 559 4 STARZEncore Action 497 4 EVINE Live 245• Trinity Broadcasting Network (TBN) 18 STARZEncore Action West 499 4 EVINE Too 246• Velocity HD 656 4 STARZEncore Black 494 4 EWTN 264•/97 Waycross 850-855+ STARZEncore Black West 496 4 FidoTV 688 WCET (PBS) Cincinnati 13 513 STARZEncore Classic 488 4 Florence 822+ WKET/Community Access 96 596 4 4 STARZEncore Classic West 490 Food Network 62 562 WKET1 294• 4 4 STARZEncore Suspense 491 FOX (WXIX) Cincinnati 3 503 WKET2 295• STARZEncore Suspense West 493 4 FOX Business Network 269• 669 WPTO (PBS) Oxford 14 STARZEncore Family 479 4 FOX News 66 566 Z Living 636 STARZEncore West 483 4 FOX Sports 1 25 525 STARZEncore Westerns 485 4 FOX Sports 2 219• 619 Variety STARZEncore Westerns West 487 4 FOX Sports Ohio (FSN) 27 527 4 AMC 33 533 FLiX 432 4 FOX Sports Ohio Alt Feed 601 4 Animal Planet 44 544 Showtime 434 435 4 Ft. -

Come Join Us in “New Zealand's Happiest Place”*

THE BULLER GUIDE TO LIVING WELL Come join us in “New Zealand’s Happiest Place”* * The Happiness of New Zealand Report – UMR Research 2012 Top 10 reasons why people move here • Easy lifestyle and quality of life • We’re kid-safe and family focused • A strong sense of community and caring • So much to see and do right on your doorstep • World-renowned scenery • Get a great house on an average wage • Getting to work, school or play takes just minutes • An unbeatable range of sport and recreation • Great retail, support services and cafes • Great transport links to main centres Click on our interactive menu and links throughout to go directly to the section you would like to see. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 10 great Housing, Perfect Place Education & Sports, Health and Culture, Relocation reasons Living for the Active Community Recreation, Wellbeing The Arts, Support Intro Essentials Retiree Learning Entertainment Heritage & Useful & Climate contacts SPACE & freedom The Buller district covers Reefton just less than 8600 square – gateway to the Buller from the Lewis Pass route from kilometers with 84% in Christchurch - born from gold in the 1860’s and now a conservation land and National modern goldmining town with a wonderfully preserved Park. All of this wonderful play heritage main street. Entry way to the magnificent Victoria Conservation Park. area for a population of around 10,000 people! Westport Choose your town – – our biggest little town of around 5,500 with all mod cons. The service centre for the Buller sited at the mouth or go country of the Buller River. -

Thinktv FACT PACK NEW ZEALAND

ThinkTV FACT PACK JAN TO DEC 2017 NEW ZEALAND TV Has Changed NEW ZEALAND Today’s TV is a sensory experience enjoyed by over 3 million viewers every week. Powered by new technologies to make TV available to New Zealanders anywhere, any time on any screen. To help advertisers and agencies understand how TV evolved over the last year, ThinkTV has created a Fact Pack with all the stats for New Zealand TV. ThinkTV’s Fact Pack summarises the New Zealand TV marketplace, in-home TV viewing, timeshifted viewing and online video consumption. And, because we know today’s TV is powered by amazing content, we’ve included information on some top shows, top advertisers and top adverts to provide you with an insight into what was watched by New Zealanders in 2017. 2017 THE NEW ZEALAND TV MARKETPLACE BIG, SMALL, MOBILE, SMART, CONNECTED, 1. HD-capable TV sets are now in CURVED, VIRTUAL, 3D, virtually every home in New Zealand DELAYED, HD, 4K, 2. Each home now has on average ON-DEMAND, CAST, 7.6 screens capable of viewing video STREAM… 3. Almost 1 in every 3 homes has a internet-connected smart TV THE TV IS AS CENTRAL TO OUR ENTERTAINMENT AS IT’S EVER BEEN. BUT FIRST, A QUICK PEAK INSIDE NEW ZEALAND’S LIVING ROOMS • In 2015 New Zealand TV celebrated 55 years of broadcast with the first transmission on 1 June, 1960 • Today’s TV experience includes Four HD Free-to-air channels Two Commercial Free-to-Air broadcasters One Subscription TV provider • Today’s TV is DIGITAL in fact, Digital TV debuted in 2006 followed by multi-channels in 2007 • In its 58th year, New Zealand TV continues to change and evolve. -

HKBN Bbtv Launches Discovery Channels

For Immediate Release HKBN bbTV launches Discovery Channels (Hong Kong, 14 January 2010) Hong Kong Broadband Network Ltd (“HKBN”), a wholly owned subsidiary of City Telecom (HK) Limited (HKSE: 1137, NASDAQ: CTEL), today announced the launch of Discovery Channels on its bbTV Pay-TV platform. Starting January 2010, HKBN customers can explore and examine the world at the 6 exciting channels offered by Discovery Networks. HKBN kicks start the 2010 New Year with a world of exploration and discovery, and expands the already comprehensive program list of bbTV with the Discovery Network suite of six channels: Discovery Channel Animal Planet Discovery Science Discovery Turbo Discovery Travel & Living Discovery Home & Health New subscribers can enjoy these new channels at US$9.10/month (HK$70) as add-on to our basic “AWSOME SPEED. FOR EVERYONE” base price of US$13/month (HK$99/month) for symmetric 100Mbps broadband service. HKBN’s Managing Director of Business Development, Ms. To Wai Bing said, “With this latest partnership, bbTV has now over 100 channels in total, offering an enriching range of TV entertainment to the audience of Hong Kong through our world class fibre broadband network. We are very confident bbTV will become the key driver for the continuous growth of our overall business and subscriptions.” Tommy Lin, senior vice president and general manager – North Asia, Discovery Networks Asia Pacific said, “Discovery is dedicated to providing the best in high-quality non-fiction entertainment, encouraging our viewers to explore the world around them and satisfy their curiosity. We are delighted with our new partnership with HKBN, where our channels can now reach more homes in Hong Kong through HKBN’s pioneering Fibre Network.” - End - 1 About City Telecom/Hong Kong Broadband Network Limited Established in 1992, City Telecom (H.K.) Limited (HKEX: 1137, NASDAQ: CTEL) provides integrated telecommunications services in Hong Kong. -

Frontier Fiberoptic TV Florida Residential Channel Lineup and TV

Frontier® FiberOptic TV Florida Channel Lineup Effective September 2021 Welcome to Frontier ® FiberOptic TV Got Questions? Get Answers. Whenever you have questions or need help with your Frontier TV service, we make it easy to get the answers you need. Here’s how: Online, go to Frontier.com/helpcenter to fi nd the Frontier User Guides to get help with your Internet and Voice services, as well as detailed instructions on how to make the most of your TV service. Make any night movie night. Choose from a selection of thousands of On Demand titles. Add to your plan with our great premium off erings including HBO, Showtime, Cinemax and Epix. Get in on the action. Sign up for NHL Center Ice, NBA League Pass and MLS Direct Kick. There is something for everyone. Check out our large selection of international off erings and specialty channels. Viewing Options: Look for this icon for channels that you can stream in the FrontierTV App or website, using your smart phone, tablet or laptop. The availability of streaming content depends on your Frontier package and content made available via various programmers. Certain channels are not available in all areas. Some live streaming channels are only available through the FrontierTV App and website when you are at home and connected to your Frontier equipment via Wi-Fi. Also, programmers like HBO, ESPN and many others have TV Everywhere products that Frontier TV subscribers can sign into and watch subscribed content. These partner products are available here: https://frontier.com/resources/tveverywhere 2 -

WHERE ARE the EXTRA ANALYSIS September 2020

WHERE ARE THE AUDIENCES? EXTRA ANALYSIS September 2020 Summary of the net daily reach of the main TV broadcasters on air and online in 2020 Daily reach 2020 – net reach of TV broadcasters. All New Zealanders 15+ • Net daily reach of TVNZ: 56% – Includes TVNZ 1, TVNZ 2, DUKE, TVNZ OnDemand • Net daily reach of Mediaworks : 25% – Includes Three, 3NOW • Net daily reach of SKY TV: 22% – Includes all SKY channels and SKY Ondemand Glasshouse Consulting June 20 2 The difference in the time each generation dedicate to different media each day is vast. 60+ year olds spend an average of nearly four hours watching TV and nearly 2½ hours listening to the radio each day. Conversely 15-39 year olds spend nearly 2½ hours watching SVOD, nearly two hours a day watching online video or listening to streamed music and nearly 1½ hours online gaming. Time spent consuming media 2020 – average minutes per day. Three generations of New Zealanders Q: Between (TIME PERIOD) about how long did you do (activity) for? 61 TV Total 143 229 110 Online Video 56 21 46 Radio 70 145 139 SVOD Total 99 32 120 Music Stream 46 12 84 Online Gaming 46 31 30 NZ On Demand 37 15-39s 26 15 40-59s Music 14 11 60+ year olds 10 Online NZ Radio 27 11 16 Note: in this chart average total minutes are based on a ll New Zealanders Podcast 6 and includes those who did not do each activity (i.e. zero minutes). 3 Media are ranked in order of daily reach among all New Zealanders. -

Download 2018 Media Guide

14–18 May 2018 Be heard A media guide for schools TOGETHER WE CAN STOP BULLYING AT OUR SCHOOL www.bullyingfree.nz Contents Why use the media? ................................................................................................... 3 Developing key messages .......................................................................................... 4 News outlets ............................................................................................................... 6 Being in the news ...................................................................................................... 9 Writing a media release ........................................................................................... 10 Tips on media interviews ......................................................................................... 12 Involving students in media activity ........................................................................... 13 Responding to media following an incident .............................................................. 14 Who we are Bullying-Free NZ Week is coordinated by the Bullying Prevention Advisory Group (BPAG). BPAG is an interagency group of 17 organisations, with representatives from the education, health, justice and social sectors, as well as internet safety and human rights advocacy groups. BPAG members share the strongly held view that bullying behaviour of any kind is unacceptable and are committed to ensuring combined action is taken to reduce bullying in New Zealand Schools. Find out more -

Critical Literacy in Support of Critical-Citizenship Education in Social Studies

TEACHING AND LEARNING Critical literacy in support of critical-citizenship education in social studies JANE ABBISS KEY POINTS • Critical-literacy approaches support justice-oriented, critical-citizenship education in social studies. • Developing learner criticality involves analysis of texts, including exploration of author viewpoints, assumptions made, matters of inclusion, and learner responses to social issues and how they are represented in texts. • Taking a critical literacy approach to support critical citizenship involves re-thinking how students in social studies engage with media sources. • Critical literacy aids informed decision-making on social issues. https://doi.org/10.18296/set.0054 set 3, 2016 29 TEACHING AND LEARNING How might social-studies teachers enact critical forms of citizenship education in classrooms and what pedagogies support this? This question is explored in relation to literature about critical citizenship and critical literacy. Also, possibilities for practice are considered and two approaches for critical literacy in social studies are presented: a) using critical questions to engage with texts; and b) focusing on media literacy in relation to current events. It is argued that critical literacy offers a collection of approaches that support justice-oriented, critical-citizenship education in social studies. Introduction Methodologically, this article presents a literature- based, small-scale practitioner inquiry relating to The aim of this article is twofold: first, to briefly challenges in supporting citizenship teaching and explore some contested views of citizenship education learning in social studies. At its core is a commitment and to consider the aims and foundations of critical to informing practice (Cochrane-Smith & Donnell, literacy as a collection of pedagogical approaches 2006; Smith & Helfenbein, 2009).