Nzjer, 2014, 39(1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Court of Appeal, 1958

The Court of Appeal, 1958 (from left) WSTICE CLEARY; WSTICE GRESSON, President; WSTICE BARROWCLOUGH, Chief Justice; WSTICE NORTH The Court of Appeal, 1968 (from left) JUSTICE McCARTHY; JUSTICE NORTH, President; JUSTICE WILD, Chief Justice; JUSTICE TURNER. Inset: Temporary judges of the Court of Appeal (left) JUSTICE WOODHOUSE; (right) JUSTICE RICHMOND. JUDGES AT WORK: THE NEW ZEALAND COURT OF APPEAL (1958-1976) BY PETER SPILLER* I. INTRODUCTION On 11 September 1957, the New Zealand Attorney-General, the Hon John Marshall, moved the second reading of the Bill for the establishment of a "permanent and separate" Court of Appeal. He declared that this was "a notable landmark in our judicial history and a significant advance in the administration of justice in New Zealand".! The Bill was duly passed and the Court commenced sitting in February 1958. In this article I shall analyse the reasons for the creation of the so-called "permanent and separate" Court of Appeal. I shall then examine the Court of Appeal judiciary, the relationship between the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court, and the work of the Court of Appeal, during the tenures of the first four Presidents of the Court. I shall conclude by assessing the extent to which the expectations of the Court at its outset were realised in the period under review. The aim of this article is to provide insight into the personalities and processes that have shaped the development of the law in the highest local Court in New Zealand. II. GENESIS OF THE "PERMANENT AND SEPARATE" COURT OF APPEAL The New Zealand Court of Appeal existed as an effective entity from February 1863, when it commenced sitting in terms of the Court of Appeal Act 1862.2 The Court had been established in response to requests by the judges for a Court within New Zealand which would provide a level of appeal more accessible than that which lay to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London.3 The Court was composed of all the judges of the Supreme Court. -

From Privy Council to Supreme Court: a Rite of Passage for New Zealand’S Legal System

THE HARKNESS HENRY LECTURE FROM PRIVY COUNCIL TO SUPREME COURT: A RITE OF PASSAGE FOR NEW ZEALAND’S LEGAL SYSTEM BY PROFESSOR MARGARET WILSON* I. INTRODUCTION May I first thank Harkness Henry for the invitation to deliver the 2010 Lecture. It gives me an opportunity to pay a special tribute to the firm for their support for the Waikato Law Faculty that has endured over the 20 years life of the Faculty. The relationship between academia and the profession is a special and important one. It is essential to the delivery of quality legal services to our community but also to the maintenance of the rule of law. Harkness Henry has also employed many of the fine Waikato law graduates who continue to practice their legal skills and provide leadership in the profession, including the Hamilton Women Lawyers Association that hosted a very enjoyable dinner in July. I have decided this evening to talk about my experience as Attorney General in the establish- ment of New Zealand’s new Supreme Court, which is now in its fifth year. In New Zealand, the Attorney General is a Member of the Cabinet and advises the Cabinet on legal matters. The Solici- tor General, who is the head of the Crown Law Office and chief legal official, is responsible for advising the Attorney General. It is in matters of what I would term legal policy that the Attorney General’s advice is normally sought although Cabinet also requires legal opinions from time to time. The other important role of the Attorney General is to advise the Governor General on the appointment of judges in all jurisdictions except the Mäori Land Court, where the appointment is made by the Minister of Mäori Affairs in consultation with the Attorney General. -

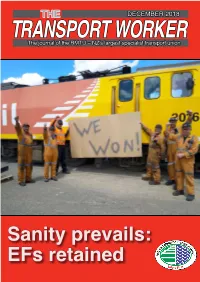

Sanity Prevails: Efs Retained 2 Contents Editorial ISSUE 4 • DECEMBER 2018

THE DECEMBER 2018 TRANSPORThe journal of the RMTU – NZ'sT largest WORKER specialist transport union Sanity prevails: EFs retained 2 CONTENTS EDITORIAL ISSUE 4 • DECEMBER 2018 12 SHANE JONES DOES HUTT SHOPS MP Shane Jones paid a visit to Hutt Workshops to familiarise himself with what the Work- shops can do and the affects of HPHE at the work face. 14 BIENNIAL CONFERENCE Wayne Butson General secretary RMTU Once again your Union held a very successful conference in Wellington with Plenty of positives a line-up of inspiring speakers. HIS time last year I wrote that rail, coastal shipping, public transport and regional development would see real gains during this Parliamentary term 36 MONGOLIAN MAGIC and that by late 2018 it would be a great time to be an RMTU member. Pare-Ana Bysterveld The good news is that by and large all has come to pass. (pictured) reports So it was with great joy that I was a member of the RMTU team to attend the Labour TParty Conference in Dunedin this year. That was its official name. However, we, and from the ICLS conference in a number of other parties, were calling it the Labour and RMTU Victory Conference. Mongolia where she Labour because, despite the nay-sayers, we remain with a viable coalition Gov- was blown away in ernment with partners working well together, and who, just one week prior, had more ways than one. announced a $35m funding of the rejuvenation of the North Island Main Trunk electric locomotives. When we launched the campaign to save the electric locos in 2016 I certainly did not fully appreciate the difficulty we would have in getting the victory and, secondly how we would pick up support from a wide range of community and environmental COVER PHOTOGRAPH: RMTU members of the groups, academics and other like-minded individuals. -

Thrf-2019-1-Winners-V3.Pdf

TO ALL 21,100 Congratulations WINNERS Home Lottery #M13575 JohnDion Bilske Smith (#888888) JohnGeoff SmithDawes (#888888) You’ve(#105858) won a 2019 You’ve(#018199) won a 2019 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 KymJohn Tuck Smith (#121988) (#888888) JohnGraham Smith Harrison (#888888) JohnSheree Smith Horton (#888888) You’ve won the Grand Prize Home You’ve(#133706) won a 2019 You’ve(#044489) won a 2019 in Brighton and $1 Million Cash BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 GaryJohn PeacockSmith (#888888) (#119766) JohnBethany Smith Overall (#888888) JohnChristopher Smith (#888888)Rehn You’ve won a 2019 Porsche Cayenne, You’ve(#110522) won a 2019 You’ve(#132843) won a 2019 trip for 2 to Bora Bora and $250,000 Cash! BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 Holiday for Life #M13577 Cash Calendar #M13576 Richard Newson Simon Armstrong (#391397) Win(#556520) a You’ve won $200,000 in the Cash Calendar You’ve won 25 years of TICKETS Win big TICKETS holidayHolidays or $300,000 Cash STILL in$15,000 our in the Cash Cash Calendar 453321 Annette Papadulis; Dernancourt STILL every year AVAILABLE 383643 David Allan; Woodville Park 378834 Tania Seal; Wudinna AVAILABLE Calendar!373433 Graeme Blyth; Para Hills 428470 Vipul Sharma; Mawson Lakes for 25 years! 361598 Dianne Briske; Modbury Heights 307307 Peter Siatis; North Plympton 449940 Kate Brown; Hampton 409669 Victor Sigre; Henley Beach South 371447 Darryn Burdett; Hindmarsh Valley 414915 Cooper Stewart; Woodcroft 375191 Lynette Burrows; Glenelg North 450101 Filomena Tibaldi; Marden 398275 Stuart Davis; Hallett Cove 312911 Gaynor Trezona; Hallett Cove 418836 Deidre Mason; Noarlunga South 321163 Steven Vacca; Campbelltown 25 years of Holidays or $300,000 Cash $200,000 in the Cash Calendar Winner to be announced 29th March 2019 Winners to be announced 29th March 2019 Finding cures and improving care Date of Issue Home Lottery Licence #M13575 2729 FebruaryMarch 2019 2019 Cash Calendar Licence ##M13576M13576 in South Australia’s Hospitals. -

The Eagle 2013 the EAGLE

VOLUME 95 FOR MEMBERS OF ST JOHN’S COLLEGE The Eagle 2013 THE EAGLE Published in the United Kingdom in 2013 by St John’s College, Cambridge St John’s College Cambridge CB2 1TP johnian.joh.cam.ac.uk Telephone: 01223 338700 Fax: 01223 338727 Email: [email protected] Registered charity number 1137428 First published in the United Kingdom in 1858 by St John’s College, Cambridge Designed by Cameron Design (01284 725292, www.designcam.co.uk) Printed by Fisherprint (01733 341444, www.fisherprint.co.uk) Front cover: Divinity School by Ben Lister (www.benlister.com) The Eagle is published annually by St John’s College, Cambridge, and is sent free of charge to members of St John’s College and other interested parties. Page 2 www.joh.cam.ac.uk CONTENTS & MESSAGES CONTENTS & MESSAGES THE EAGLE Contents CONTENTS & MESSAGES Photography: John Kingsnorth Page 4 johnian.joh.cam.ac.uk Contents & messages THE EAGLE CONTENTS CONTENTS & MESSAGES Editorial..................................................................................................... 9 Message from the Master .......................................................................... 10 Articles Maggie Hartley: The best nursing job in the world ................................ 17 Esther-Miriam Wagner: Research at St John’s: A shared passion for learning......................................................................................... 20 Peter Leng: Living history .................................................................... 26 Frank Salmon: The conversion of Divinity -

Professor Richard Epstein and the New Zealand Employment Contract

Wailes: Professor Richard Epstein and the New Zealand Employment Contract PROFESSOR RICHARD EPSTEIN AND THE NEW ZEALAND EMPLOYMENT CONTRACTS ACT: A CRITIQUE NICK WAILES* Penelope Brook, one of the major proponents of radical reform in the New Zealand labor law system, has characterized the New Zealand Em- ployment Contracts Act (ECA) as an "incomplete revolution."' She argues that this "incompleteness" stems from the retention of a specialist labor law jurisdiction and the failure to frame the Act around the principle of contract at will.2 The emphasis placed on these two issues-specialist jurisdiction and contract at will-demonstrates the influence arguments made by Chi- cago Law Professor, Richard Epstein, have played on labor law reform in New Zealand. Despite reservations about its final form, Brook gives her support to the ECA, precisely because it operationalizes some of Epstein's ideas. It has been generally acknowledged that ideas like those of Epstein played a significant role in the introduction of the ECA in New Zealand. However, while critics of the ECA have acknowledged the importance of Epstein's ideas in the debate which led up to the passing of the Act, few at- tempts have been made to outline clearly or critique Epstein's views. This Paper attempts to fill this lacuna by providing a critique of the behavioral assumptions that Epstein brings to his analysis of labor law. The first sec- * The Department of Industrial Relations, The University of Sydney, Australia. This is an amended version of Nick Wailes, The Case Against Specialist Jurisdictionfor Labor Law: PhilosophicalAssumptions of a Common Law for Labor Relations, 19 N.Z.J. -

Accident Compensation in Swiss and New Zealand

ACCIDENT COMPENSATION IN SWISS AND NEW ZEALAND LAW – SOME SELECTED ISSUES THAT UNDERMINE THE PURPOSE IN BOTH SCHEMES By Yvonne Wampfler Rohrer A dissertation submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Laws Victoria University of Wellington 2009 ABSTRACT This dissertation analyses selected issues that undermine the coherence and the purposes of the Swiss and New Zealand accident compensation schemes. Unlike other European states the Swiss accident compensation provides cover for non-work related accidental injury, which makes it a useful subject of comparison with the New Zealand accident compensation scheme which provides a comprehensive, no fault compensation scheme for personal injury. In undertaking a largely comparative approach the paper argues that both schemes have drifted away considerably from the original underlying purpose to provide compensation for work incapacity and, on the other hand, to restore the claimant to a level of work capacity as soon as possible. This thesis is illustrated by examining the vulnerability of the schemes to political change, the arbitrary dichotomy between incapacity to work caused by accidental injury and incapacity caused by sickness, the definitions of an accident in both schemes and the assessment of evidence. The paper finds that both schemes should be amended and suggests alternative approaches for each issue. STATEMENT ON WORD LENGTH The text of this paper (excluding abstract, table of contents, table of cases, -

Blood on the Coal

Blood on the Coal The origins and future of New Zealand’s Accident Compensation scheme Blood on the Coal The origins and future of New Zealand’s Accident Compensation scheme Hazel Armstrong 2008 Oh, it’s easy money stacking carcasses in the half-dark. It’s easy money dodging timber that would burst you like a tick. yes, easy as pie as a piece of cake as falling off a log. Or being felled by one. extract from The Ballad of Fifty-One by Bill Sewell Hazel Armstrong is the principal of the Wellington firm Hazel Armstrong Law, which specialises in ACC law, employment law, occupational health and safety, occupational disease, vocational rehabilitation and retraining, and employment-related education. ISBN no. 978-0-473-13461-7 Publisher: Trade Union History Project, PO Box 27-425 Wellington, www.tuhp.org.nz First edition printed 2007 Revised and expanded edition printed May 2008 Acknowledgements The author would like to thank: Social Policy Evaluation and Research Linkages (SPEARS) funding programme for the Social Policy Research Award Rob Laurs for co-authoring the first edition Hazel Armstrong Law for additional funding to undertake the research Dr Grant Duncan, Senior Lecturer in Social and Public Policy Programmes, Massey University, Albany Campus, for academic supervision Sir Owen Woodhouse, Chair, Royal Commission of Inquiry into Compensation for Personal Injury in New Zealand (1969) for discussing the origins of the ACC scheme Mark Derby for editing the draft text Dave Kent for design and production DISCLAIMER The views expressed in this paper should not be taken to represent the views or policy of the Social Policy Evaluation and Research Committee (‘SPEaR’). -

GLOBALISATION, SOVEREIGNTY and the TRANSFORMATION of NEW ZEALAND FOREIGN POLICY Robert G

Working Pape Working GLOBALISATION, SOVEREIGNTY AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF NEW ZEALAND FOREIGN POLICY Robert G. Patman Centre for Strategic Studies: New Zealand r Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. No.21/05 CENTRE FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES NEW ZEALAND Working Papers The Centre for Strategic Studies Working Paper series is designed to give a forum for scholars and specialists working on issues related directly to New Zealand’s security, broadly defined, and to the Asia-Pacific region. The Working Papers represent ‘work in progress’ and as such may be altered and expanded after feedback before being published elsewhere. The opinions expressed and conclusions drawn in the Working Papers are solely those of the writer. They do not necessarily represent the views of the Centre for Strategic Studies or any other organisation with which the writer may be affiliated. For further information or additional copies of the Working Papers please contact: Centre for Strategic Studies: New Zealand Victoria University of Wellington PO Box 600 Wellington New Zealand. Tel: 64 4 463 5434 Fax: 64 4 463 5737 Email: [email protected] Website: www.vuw.ac.nz/css/ Centre for Strategic Studies Victoria University of Wellington 2005 © Robert G. Patman ISSN 1175-1339 Desktop Design: Synonne Rajanayagam Globalisation, Sovereignty, and the Transformation of New Zealand Foreign Policy Working Paper 21/05 Abstract Structural changes in the global system have raised a big question mark over a traditional working principle of international relations, namely, state sovereignty. With the end of the Cold War and the subsequent break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991, the US has been left as the world’s only superpower. -

Trans Tasman Politics, Legislation, Trade, Economy Now in Its 50Th Year 22 March Issue • 2018 No

www.transtasman.co.nz Trans Tasman Politics, Legislation, Trade, Economy Now in its 50th year 22 March Issue • 2018 No. 18/2115 ISSN 2324-2930 Comment Tough Week For Ardern If Jacinda Ardern is in the habit of asking herself whether she’s doing a good job at the end of each week, she’ll have had the first one when the answer has probably been no. It has been a week in which she has looked less like a leader than she has at any time so far in her time as head of the Labour Party and then Prime Minister. Jacindamania is fading. The tough reality of weekly politics is taking over. The Party apparatus has dropped her in it – but she seems powerless to get rid of the source of the problem, because while she is Prime Minister, she’s not in charge of the party. The party seems to have asserted its rights to do things its own way, even if this means keeping the PM in the dark about a sex assault claim after an alleged incident at a party function. Even a Cabinet Minister knew and didn’t tell her. This made Ardern look powerless. Her coalition partner, Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Winston Peters also led her a merry dance this week over the Russia Free Trade agreement the two parties agreed to pursue as part of their coalition agree- ment. Peters unfortunately chose a week in which Russia was accused of a deadly nerve agent attack on one of its former spies in Britain to up the ante on pushing the FTA forward. -

Publ 408/Pols 436 State and the Economy – Globalisation Issues

School of Government PUBL 408/POLS 436 STATE AND THE ECONOMY – GLOBALISATION ISSUES Trimester 1 2007 COURSE OUTLINE Contact Details Course Co-ordinator: Dr John Wilson RH 212 Tel: 04 463 5082 [email protected] [email protected] Office hours: Wednesday 1.00pm – 2.30pm; other times by appointment. Administrator: Francine McGee RH 821 (Reception) 04 463 – 6599 [email protected] Class Times and Room Numbers Lectures: Wednesday 2.40pm – 4.30pm GB117 Additional information will be posted on the departmental notice board, or announced in class. Course aims and objectives The state and the market represent two different approaches to organising human behaviour, and the relationship between them has always affected the conduct of public policy. A key theme of the course is the way in which states manage their economic development within an international context increasingly characterised by patterns of globalisation. While globalisation may enhance a nation’s economic prosperity, it also has implications for the ability of national governments to autonomously pursue economic, social, and environmental objectives. Case studies examine how the pursuit of economic development goals can conflict with wider policy objectives in the energy, environmental, trade, and social policy areas. 1 By the end of the course, students should be able to: appreciate the evolution of the state- economy relationship: understand the role of government in managing the economy; understand and critique the challenges posed by globalisation to national and economic development; show to what extent states can autonomously pursue their public policy goals in the era of globalisation. -

Manufacturing: the New Consensus a Blueprint for Better Jobs and Higher Wages June 2013 Contents

Manufacturing: The New Consensus A Blueprint for Better Jobs and Higher Wages June 2013 Contents Acknowledgments Executive Summary Recommendations Chapter 1: The Inquiry Introduction Terms of reference Chair, membership and meetings Chapter 2: Manufacturing in New Zealand: contemporary structure and background Manufacturing in New Zealand: background The Contemporary Debate The Strategic Dimension The Global Future of Manufacturing Chapter 3: Analysing the Submissions Passion and Commitment The Pressing Challenges The Broader Factors Chapter 4: Ways forward and Recommendations Bibliography 2 Acknowledgements The Chair wishes to acknowledge the support offered to the Inquiry by many people. The many submitters are to be congratulated for the time and effort involved in writing and presenting wide-ranging, informed and often passionate submissions. The MPs, who constituted the Inquiry panel, or who participated during its hearings, devoted much time and effort to its successful conclusion. The support staff, and, in particular, Richard Bicknell, who managed the logistics of the Inquiry and 3 Executive Summary The message of this Inquiry and Report is simple: a strong and successful manufacturing sector is vital for improved export performance, better jobs and higher incomes in New Zealand. Moreover, we can do a great deal more to support a sector that has been marginalised for a generation and faces continuing pressure on many fronts. Whilst recognising that the primary sector will always play an important role in our economy, it alone cannot deliver the standard of living to which we aspire, especially as our population grows. Submitters have described in great detail the challenges they face under current policy settings, especially in comparison with manufacturers in other countries.