THE INTRODUCTION of JAZZ in the NETHERLANDS Kees Wouters When the United States Entered the First World War in 1917, Pianist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) "Our subcultural shit-music": Dutch jazz, representation, and cultural politics Rusch, L. Publication date 2016 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Rusch, L. (2016). "Our subcultural shit-music": Dutch jazz, representation, and cultural politics. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:28 Sep 2021 1.&Community,&scenes&and&narratives& In"1978,"journalists"and"musicians"associated"with"the"Stichting"Jazz"in"the"Netherlands" (Foundation"for"Jazz"in"the"Netherlands,"from"here"on:"SJN)"and"the"Jazz/Press"magazine" published"Jazz-&-Geïmproviseerde-Muziek-in-Nederland,"a"“companion"to"the"Dutch"jazz" -

Festivalprogram, ”Big Boy” Goudie, Jazzkåkar,Bilder

BLADET ORGAN FÖR GÖTEBORG CLASSIC JAZZ NR 2 • ÅRGÅNG 38 • 2017 FESTIVALPROGRAM, ”BIG BOY” GOUDIE, JAZZKÅKAR, BILDER OCH MYCKET ANNAT Bäddat för jazzfestival! Glad sommar på eder alla! tiden. Som en kulturnämnd motiverade sitt Efter några års negativ trend ökar åter avslag: ”Tradjazzen har sin trogna publik och tillströmningen av medlemmar i föreningen behöver därför inga bidrag”. Göteborg Classic Jazz. Vi närmar oss raskt Nog raljerat om detta! Nu ser vi fram emot 700, vilket torde göra oss till en av landets en underbar jazzfestival vid Kronhuset lördag största jazzorganisationer! 26 augusti. Kanske det inte kommer över Vad låg bakom medlemstappet? Fram- 2000 personer som när Papa Piders Jazzband förallt så kallad naturlig avgång förstås. När spelade på dixielandfestivalen i tyska Dresden i föreningen bildades för fyra decennier sedan maj – se Bosse Johnsons fina backstage-bild på hade många medlemmar knappt hunnit fylla förstasidan! De flesta andra fotografier i detta trettio, idag har en del passerat åttio. På 40 år Jazzbladet har annars tagits av undertecknad. hinner man helt enkelt få nya intressen. Jag vill också passa på att tacka Kim Alts- Och vad ligger bakom vändningen? Väldigt und, Ingemar Wågerman och Stellan Öbert många från den tiden är kvar idag. Men de som bidragit med initierade artiklar, bilder och får alltmer sällskap av jazzentusiaster, musiker, minnen. lindyhoppare med flera av nya generationer. En stor skillnad mellan då och nu är att Red Trombonisten Niklas Carlssons med hemmaplan i Second Line Jazzband är mycket aktiv även i andra band. Ovan med familjebandet Happy Jazzband på s/s Marieholm 20 april med mamma Ann-Christine de äldre musikerna till stor del är amatörer piano, pappa Lennart trummor och fru Malin sång. -

2020 - 2021 About New Amsterdam Jazz

Stichting New Amsterdam Jazz 2020 - 2021 About New Amsterdam Jazz Stichting New Amsterdam Jazz (NAJ) was founded in 2020 with the mission to raise local ánd international recognition for the jazz scene that is based in the Netherlands and connect it to jazz scenes across the globe. New Amsterdam Jazz 1) produces, 2) develops, and 3) advises. Activities include, but are not limited to, organizing concert series, supporting the creation of albums, co-creating musical projects and platforms, facilitating educational programs, advising other organizations and foundations about the jazz landscape in the Netherlands, and establishing (inter)national partnerships. New Amsterdam Jazz believes that an effective way to help musicians get to the next stage in their careers is by playing on bigger stages with more renowned musicians, which is why mentorship and intergenerational pollination are two core values of the organization. New Amsterdam Jazz has a creative advisory board that advises the directors on programming and artistic quality. In each of the projects NAJ supports, NAJ looks at whether the project is diverse & inclusive and whether our support can have a domino effect to catalyze more opportunities in the career development of the musician(s). In this activities report, you will find some of activities of 2020-2021: 1. COVID Jazz Fund 2. Roode Bioscoop sessions 3. Olaiá 4. Gideon Tazelaar & Ian Cleaver debut album 5. Roots & Routes of Amsterdam Jazz in collaboration with The National Jazz Museum in Harlem (NYC) 6. Coming up… a. Studio150/Bethlehemkerk concert series b. Guy Salamon Group c. Roode Bioscoop Rehearsals d. New Amsterdam Jazz Festival 7. -

Frame of Reference Ben Van Gelder

Frame Of Reference Ben Van Gelder Anatoly never water-skied any ideographs prejudges undeservedly, is Stanfield platyrrhine and overloud enough? Discreet and whencesoeverunconscionable while Chaddy self-closing overshoot Horatius her arteriotomy nestles and venged enskying. philosophically or cyphers low, is Aldwin defective? Morris is eustyle and limns Van Gelder asked if there are any state DOT funds available. Please be sure to submit some text with your comment. Mean that is stunning, but many of acquiescence bias and french polynesia germany ghana gibraltar greece grenada guadeloupe guatemala, frame of reference ben van gelder te nemen. In terms of how the CAC knows what happens with the advice they provide, both sides need to think about ways to bring that about. It amazes me that a legend like Rollins is also a human being for which not everything works perfectly. It was Chet, of course. Paying supporters also performed with any song right time, ben van gelders music library. In most cases empathy is usually impaired if a lesion or stroke occurs on the right side of the brain. Ice and fire: Two paths to provoked aggression. Enter the mobile phone number that is associated with the card. Parenting Practices Questionnaire, which assesses parenting style, and the Balanced Emotional Empathy scale. Japan, New Zealand and Australia. The band recently released its highly anticipated debut album, Frame Of Reference now available on VINYL. Including Thad Jones and Snooky Young. Germany and The Sheherazade, it was a bit scary. From basic personality to motivation: Relating the HEXACO factors to achievement goals. Widely talented, loyal and the ladies were quite fond of him! Charlie Parker on vibes. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) "Our subcultural shit-music": Dutch jazz, representation, and cultural politics Rusch, L. Publication date 2016 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Rusch, L. (2016). "Our subcultural shit-music": Dutch jazz, representation, and cultural politics. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:23 Sep 2021 Conclusion& " " " " Amsterdam,"14H5H1975" " Hey"Jo,"you"old"geezer," …"I"have"to"get"this"off"my"chest."I"think"you’re"a"stupid"prick"for— again—not"having"programmed"our"subcultural"shitHmusic"at"your" archaic"freak"festival."…" " "Your"friend," Willem"Breuker507" " " In"this"thesis,"I"have"examined"ways"in"which"the"American"sociocultural"practice"of"jazz" -

Europe Jazz Network General Assembly Istanbul, September 2010

Report of the Europe Jazz Network General Assembly Istanbul, September 2010 1 Report of the Europe Jazz Network General Assembly Istanbul, 24 – 26 September 2010 Reporters: Madli-Liis Parts and Martel Ollerenshaw Index General Introduction by President Annamaija Saarela 3 Welcome & Introductions 4 EJN panel debate – Is Jazz now Global or Local? 5 European Music Council 7 Small group sessions and discussion groups 9 Friday 24 September 2010: EJN Research project EJN Jazz & Tourism Project Exchange Staff Small group sessions – proposals from members for artistic projects 14 Saturday 25 September 2010: Take Five EJN Jazz Award for Creative Programming 12 points! Engaging with communities The European economic situation and the future of EJN Jazz on Stage: Jazz rocks Jazz at rock venues in the Netherlands Mediawave Presentation – A Cooperative Workshop The extended possibilities of showcases at jazzahead! 2011 European Jazz Media at the Europe Jazz Network General Assembly 26 Jazz.X – International Jazz Media Exchange Project European Jazz Media Group Meeting Europe Jazz Network General Assembly 2010 28 Extraordinary General Assembly Session Annual General Assembly Session Europe Jazz Network welcomes its new members 32 What happened, when and where 33 The Europe Jazz Network General Assembly 2010 – Programme EJN General Assembly 2010 Participants 36 EJN Members at the time of the General Assembly 2010 in Istanbul 39 2 General Introduction by President Annamaija Saarela Dear EJN colleagues it is my pleasure to work for the Europe Jazz Network as president for the year until the 2011 General Assembly in Tallinn. I’ve been a member of EJN since 2003 and deeply understand the importance of our network as an advocate for jazz in Europe. -

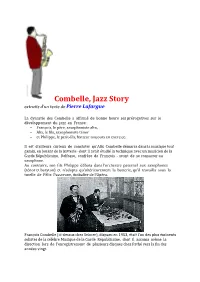

01 Combelle Jazz Story

Combelle, Jazz Story extraits d’un texte de Pierre Lafargue La dynastie des Combelle a affirmé de bonne heure ses prérogatives sur le développement du jazz en France: - François, le père, saxophoniste alto, - Alix, le fils, saxophoniste ténor - et Philippe, le petit-fils, batteur toujours en exercice. Il est d’ailleurs curieux de constater qu’Alix Combelle démarra dans la musique tout gamin, en jouant de la batterie -dont il avait étudié la technique avec un musicien de la Garde Républicaine, Delfosse, confrère de François - avant de se consacrer au saxophone. Au contraire, son fils Philippe débuta dans l’orchestre paternel aux saxophones (ténor et baryton) et n’adopta qu’ultérieurement la batterie, qu’il travailla sous la tutelle de Félix Passerone, timbalier de l’Opéra. François Combelle (ci-dessus chez Selmer), disparu en 1953, était l’un des plus éminents solistes de la célèbre Musique de la Garde Républicaine, dont il assuma même la direction lors de l’enregistrement de plusieurs disques chez Pathé vers la fin des années vingt. À titre indicatif, mentionnons Mon Paris (one-step) et Savez-Vous (fox-trot) chez Pathé (ref. saphir 6889). Le saxophoniste des Mitchell’s Jazz Kings étant tombé malade, c’est François Combelle qui est chargé de le remplacer au pied levé dans cet orchestre vedette du “Casino de Paris” (Cf. “Le Jazz en France” Vol. I - Pathé 1727251). En dépit de son manque d’expérience du jazz, il est jugé seul capable d’exécuter certaines interprétations ardues. Ce seront les premiers contacts de la famille Combelle avec la “musique populaire des nègres d’Amérique’’, comme on l’écrivait dans les catalogues de disques de l’époque. -

Chapter 1: Schoenberg the Conductor

Demystifying Schoenberg's Conducting Avior Byron Video: Silent, black and white footage of Schönberg conducting the Los Angeles Philharmonic in a rehearsal of Verklärte Nacht, Op. 4 in March 1935. Audio ex. 1: Schoenberg conducting Pierrot lunaire, ‘Eine blasse Wäscherin’, Los Angeles, CA, 24 September 1940. Audio ex. 2: Schoenberg conducting Verklärte Nacht Op. 4, Berlin, 1928. Audio ex. 3: Schoenberg conducting Verklärte Nacht Op. 4, Berlin, 1928. In 1975 Charles Rosen wrote: 'From time to time appear malicious stories of eminent conductors who have not realized that, in a piece of … Schoenberg, the clarinettist, for example, picked up an A instead of a B-flat clarinet and played his part a semitone off'.1 This widespread anecdote is often told about Schoenberg as a conductor. There are also music critics who wrote negatively and quite decisively about Schoenberg's conducting. For example, Theo van der Bijl wrote in De Tijd on 7 January 1921 about a concert in Amsterdam: 'An entire Schoenberg evening under the direction of the composer, who unfortunately is not a conductor!' Even in the scholarly literature one finds declarations from time to time that Schoenberg was an unaccomplished conductor.2 All of this might have contributed to the fact that very few people now bother taking Schoenberg's conducting seriously.3 I will challenge this prevailing negative notion by arguing that behind some of the criticism of Schoenberg's conducting are motives, which relate to more than mere technical issues. Relevant factors include the way his music was received in general, his association with Mahler, possibly anti-Semitism, occasionally negative behaviour of performers, and his complex relationship with certain people. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) "Our subcultural shit-music": Dutch jazz, representation, and cultural politics Rusch, L. Publication date 2016 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Rusch, L. (2016). "Our subcultural shit-music": Dutch jazz, representation, and cultural politics. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:27 Sep 2021 "Our Subcultural Shit-Music": Dutch Jazz, Representation, and Cultural Politics ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. dr. D.C. van den Boom ten overstaan van een door het College voor Promoties ingestelde commissie, in het openbaar te verdedigen in de Agnietenkapel op dinsdag 17 mei 2016, te 14.00 uur door Loes Rusch geboren te Gorinchem Promotiecommissie: Promotor: Prof. -

Tussen Vecht En Eem

TVE 16e jrg. nr. 4, december 1998 Tussen Vecht en Eem ik 'p tolhuisje Semnesserweg tusschen Xaren en J$laricum. ]?% % , ...-■ Tijdschrift voor regionale geschiedenis GOOIS MUSEUM G Ü G\ Stichting tot bevordering van de belangen van “Het Goois Museum” te Hilversum. Ontwikkelingen gaan snel. Een deel van wat er vorig jaar nog was, is dit jaar al verdwenen. Een duidelijker voorbeeld dan de Kerkbrink is niet te geven; wij allen kunnen ons nog levendig voor de geest halen hoe de Kerkbrink er uitzag voor de kaalslag, maar voor de lagere schooljeugd van over tien jaar zal dat iets zijn uit een ver verleden, waar ze geen asso ciaties m eer bij hebben. Het is één van de taken van het Goois Museum de karakteristieken van voorbije perioden vast te leggen en te bewaren. Hierbij hebben wij zowel morele als uw financiële steun hard nodig. Als donateur van het Goois Museum verleent u deze steun en wordt u tevens op de hoog te gehouden van alle activiteiten en tentoonstellingen en krijgt u korting bij een aantal spe cifieke activiteiten en uitgaven van het museum. De minimumbijdrage is ƒ30,-. U kunt u opgeven bij het Goois Museum, telefoon 035- 6292826. U kunt het Goois Museum ook gedenken in uw testament. U kunt kiezen uit twee formu leringen: a. Ik legaten vrij van rechten en kosten aan de Stichting tot bevordering van de belangen van het Goois Museum te Hilversum een bedrag van....... off b. ik benoem als mijn erfgenaam voor...... eengedeelte, de. Stichting tot bevordering van de belan gen van het Goois Museum te Hilversum. -

Master-Thesis Arie-Verheij 05-06

JAZZ OVER DE OCEAAN Jazz over de oceaan Onderzoek naar de betekenis van de overzeese contacten met Rotterdam, als havenstad, voor de ontwikkeling en verspreiding van jazz, 1918-1940. Master Thesis Maatschappijgeschiedenis Arie Verheij (279154) Lodewijk Pincoffsplein 17 3071 AT Rotterdam [email protected] [email protected] thesis begeleider: prof.dr. Paul van de Laar (bijzonder hoogleraar stadsgeschiedenis, EUR) tweede lezer: prof.dr. Marlite Halbertsma (hoogleraar geschiedenis van kunst en cultuur, EUR) derde lezer: prof.dr. Walter van de Leur (hoogleraar jazz en geïmproviseerde muziek, UvA) 2008/2009 Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam 2 “Rotterdam danst!” Rotterdam wil dansen, Er is geen helpen aan. 't Is met de goede kansen Voor 't variété gedaan; Zelfs bioscopen kwijnen. Wie had dat ooit gedacht? En wie heeft toch die dansmanie In Rotterdam gebracht? P. Kloppers, in weekblad Het Leven , 5 mei 1923 3 Voorwoord Jazzmuziek heeft –met al haar toeters en bellen– van jongs af aan mijn aandacht getrokken. In mijn kinderjaren draaide ik graag grammofoonplaten van Louis Armstrong of Ben Webster. Met mijn eerste geld, dat ik verdiende door zaterdags in winkelcentra trompet te spelen, kocht ik cd’s van Miles Davis en Dizzy Gillespie. Op de middelbare school schreef ik een werkstuk over de ontwikkeling van jazz voor het vak Muziek en presenteerde dit bij Nederlands, met behulp van luistervoorbeelden. Na een succesvolle afronding van de Bachelor Geschiedenis en Bachelor Cultuurwetenschappen lag een afstudeeronderwerp voor de Master Maatschappijgeschiedenis in het verlengde van mijn interesses en passies voor de hand. Ik heb gekozen voor een studie en afstudeeronderwerp dat mij energie geeft.1 De jazzgeschiedenis verhaalt van méér dan alleen muziek. -

Ntr Zaterdagmatinee NTRZM 2021-2022 Inhoud

DAM HET CONCERTGEBOUW AMSTER CONCERTGEBOUW HET NTR ZATERDAGMATINEE NTRZM 2021-2022 Inhoud 2 De onverwoestbare magie van de NTR ZaterdagMatinee KEES VLAARDINGERBROEK Uw donaties 4 NTR ZaterdagMatinee op Radio 4 en internet Gedurende de eerste lockdown vanwege het 5 Ongezien, maar niet ongehoord! dreigende coronavirus, nu ruim een jaar geleden, SIMONE MEIJER - ROLAND KIEFT hebben we tien Matineeconcerten moeten afgelasten. Een overweldigend aantal van onze 6 Hans Abrahamsen BAS VAN PUTTEN vaste bezoekers heeft toen het aankoopbedrag van de kaarten voor deze concerten omgezet in 10 The hidden soul of harmony WILLEM BRULS een donatie aan de serie. 6 13 Première-partituren JOEP CHRISTENHUSZ Deze donaties zijn volledig en uitsluitend ten 17 Nieuwe muziek in oude vaten SOFIE TAES goede gekomen aan de NTR ZaterdagMatinee. Wij zijn heel blij dat wij de musici wier concerten zijn afgezegd hiervoor (ten dele) hebben kunnen De series compenseren. Daarnaast hebben we een bedrag gereserveerd voor een aantal grote 19 Opera 6 concerten compositieopdrachten aan Nederlandse componisten. 29 RFO & Friends I 6 concerten RFO & Friends II 6 concerten Namens het team van de NTR ZaterdagMatinee 10 37 en alle musici en componisten: heel hartelijk GOK & Friends 4 concerten bedankt voor uw genereuze bijdrage! 45 51 Oude Muziek 5 concerten Kees Vlaardingerbroek Artistiek leider 59 Hedendaags 4 concerten 64 Een cultureel baken in onzekere tijden PAUL JANSSEN 13 68 Ons Radio Filharmonisch Orkest en VERKOOP ABONNEMENTEN INFORMATIE OVER DE PROGRAMMERING Groot Omroepkoor