Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

360° Brand Engagement Presented by Munson Steed • (404) 635-1313 Ext

360° Brand Engagement Presented by Munson Steed • (404) 635-1313 ext. 113 • [email protected] Steed Media Is… DIGITAL PRINT •… a multimedia powerhouse with national reach. •…a year-round print presence in 19 of the top 25 urban DMAs •…a specialist in localization and nationalization, thanks to our network of city managers MOBILE SOCIAL •…an ideal urban marketing extension specializing in 360 degree integration and partnerships What Steed Media does… CUSTOM VIDEO ON • Custom publications PUBLISHING & DEMAND •Editorial Development INTEGRATION • Direct consumer engagement opportunities • Public Relations •Marketing and Brand Strategy •Content Propagation PHOTO & •Facilitation of app, software and technology EVENTS VIDEO development SERVICES •On-Demand cable exposure • Custom microsite design and management • Television production •We turn ideas into profits! A M E D I A A N D BRANDING SOLUTION 360° Degree Integrated Engagement of the Urban Consumer Print The nation’s largest chain of African-American newspapers, in 19 of the Top 25 AA markets. Events/Promotions Aimed at producing brand-engagement experiences, onsite activations and purchase activities. Digital Original content that rides the pulse of Urban America. Mobile Site Keeping Urban America’s lifestyle elements at their fingertips…even on the go Custom Publications Using the power of relevance to drive brand consideration. Video On Demand Harnessing the power of an engaged audience. A M E D I A A N D BRANDING SOLUTION Audience Demographics A M E D I A A N D BRANDING SOLUTION Print At nearly 40 million, the African- American population represents more than 13% of the U.S. population, is growing faster than the general population, and is experiencing faster income growth than the rest of the population. -

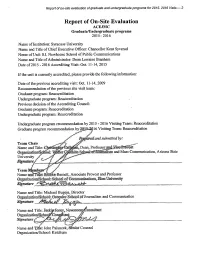

2015-16-Syracuse-Team-Report-And

PART I: General information Name of Institution: Syracuse University Name of Unit: S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications Year of Visit: 2015 Executive Summary: • The School’s skills courses comply with the ACEJMC mandate of no more than 20 students per section. • The Newhouse School’s Mission Statement is a part of its Strategic Plan, which is written to cover all academic programs in the School. It reinforces the School’s commitment to graduating communication leaders with a solid liberal arts foundation. Graduate students are selected in keeping with this mandate; the vast majority of them come to the School with baccalaureate education that has a focus on the liberal arts. Their rigorous professional Master’s education is designed in part to build from that liberal arts foundation. From there, the mandate that we graduate leaders who are agile, ethically responsible, who embrace diversity and who can demonstrate cutting-edge skill requires the Professional Master’s programs to concentrate uniquely rigorous activities into their shorter and more intense time frames. 1. Check regional association by which the institution now is accredited. X Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools _ New England Association of Schools and Colleges _ North Central Association of Colleges and Schools _ Northwest Association of Schools and Colleges _ Southern Association of Colleges and Schools _ Western Association of Schools and Colleges 2. Indicate the institution’s type of control; check more than one if necessary. X Private _ Public _ Other (specify) Report of on-site evaluation of graduate and undergraduate programs for 2015- 2016 Visits — 2 3. -

Joan B. Kroc Institute for Peace & Justice

OCTOBER 5-7, 2011 5-7, OCTOBER WOMEN, MEDIA, Laura Bifano Laura A public forum held in conjunction with the 2011 IPJ Women PeaceMakers Program REVOLUTION Sponsored by the Fred J. Hansen Foundation “Encounters with women who can change worlds” Joan B. Kroc Institute for Peace & Justice LUCY STONE 1818-1893 Now all we need is to continue to speak the truth fearlessly, and “ we shall add to our number those who will turn the scale to the side of equal and full justice in all things. ” October 5, 2011 Welcome to “Women, Media, Revolution,” It has been said that the one who writes the stories determines history. Women correspondents, directors and citizen journalists who are invested in capturing the broader array of community voices can open doors to different futures leading away from the seemingly endless cycles and costs of conflict. Women and men sensitive to gender-inclusive perspectives commonly take steps toward justice by documenting more than the facades and remnants of events. In doing so, they take risks, confront – and occasionally influence – conventional reporting or move beyond the comfortably entrenched traditional authorities who remain unable or unwilling to let go of habitual points of view. We applaud brave, committed storytellers, many who are gathered here for “Women, Media, Revolution.” While representing various forms of media, each has been successful in locating humanity in the myriad of troubles they have covered. Disclosing the stories of the venerable and vulnerable, the powerful and the humble, and those who risk everything in revolutionary calls for justice, these storytellers are courageous themselves. -

Syracuse University S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications Fall 2007 Vol

SyracuSe univerSity S.i. newhouSe School of Public communicationS fall 2007 vol. 19 no. 3 SyracuSe univerSity S.i. newhouSe School of Public communicationS fall 2007 vol. 19 no. 3 Dean in this issue: David M. Rubin Executive Editor Dean’s Column 1 Wendy S. Loughlin G’95 Newhouse III Dedication 2 Editor Carol L. Boll Year of the First Amendment 6 Contributors Jean Brooks First Amendment Scholars Program 7 Rob Enslin Shavon S. Greene ’10 2 Newhouse in New York 8 Kathleen Haley ’92 Jason Levy G’07 Agatha Lutoborski ’08 Executive Education 9 Kevin Morrow Christy Perry TRF Semester Study 10 George Thomas G’07 Nhouse Productions 11 Photography Steve Sartori Images of the South Side 12 Graphic Design Elizabeth Percival 7 Emergency Preparedness 14 Assistant Dean of External Relations Student News 15 Lynn A. Vanderhoek ’89 Mirror Awards 16 Office of External Relations Ivory Tower Goes Statewide 17 315-443-5711 Web Site Envi Magazine 17 newhouse.syr.edu 8 Faculty Briefs 18 On the cover: Newhouse III “ribbon-cutting” Lauren Pomerantz ’03 20 participants (from left) Stephanie Rivetz ’08, S.I. Newhouse Jr., William Kagler ’51 22 Victoria Newhouse, U.S. Chief Justice John Roberts Jr., Chancellor Class Notes 23 Nancy Cantor, Donald Newhouse, Susan Newhouse, and Dean David Rubin 9 Newhouse III is now open. Students are finding their • Scholarship assistance. We are increasingly coziest hideaways for studying and socializing. The competing for students with Ivy League schools favorite food items at Food.com are becoming clear. and others with much larger endowments. To Faculty members and students are learning their way remain competitive for these students, we need around the new experimental newsroom. -

OPC Attends JPC Freedom of the Press Conference Panelists

MONTHLY NEWSLETTER I June 2017 Panelists Discuss the Future of Journalism and Mentorship With The Media Line INSIDE hosted to discuss the crucial link EVENT RECAP Event Recap: between policy and journalism Preview of ‘Letters by chad bouchard and to celebrate the agency’s Press From Baghdad’ 3 and Policy Student Program. The any journalists and Event Recap: program offers students studying media watchers have Screening of journalism, public policy or interna- voiced growing concern ‘Hell on Earth’ 4 M tional relations one- about the future of journalism in on-one mentorships, Event Recap: an era of constant challenges and Foreign Editors Circle GREGORY PARTANIO GREGORY either remote or Click here uncertainty. With diminishing trust by Michael Serrill 5 on-site in the to watch video in traditional media, sound reporting Felice Friedson, left, talks to Shirley from the event. Middle East with 6-8 dismissed as “fake news” and blatant and Arthur Sotloff. People Column The Media Line falsehoods passing for news content, news bureau’s veteran Press Freedom the information stream has been Update 9-10 cy covering the Middle East, told at- journalists. Selected students can polluted. tendees during a recent forum at the earn academic credit or pursue inde- “Many of us are disgusted when Q&A: OPC. “I tell you that our forefathers pendent study. Yaroslav Trofimov 11 we look at the media and try to un- would turn in their graves.” Former OPC President David derstand what is going on,” Felice 12 Friedson made her remarks on Andelman, who serves on the pro- New Books Friedson, president and CEO of The Tuesday, June 13 at an event that Media Line, an American news agen- the OPC and The Media Line co- Continued on Page 2 OPC Attends JPC Freedom of the Press Conference staff cuts and the closing of for- McClatchy, the Miami Herald and interaction with subscribers. -

Wasimahmad.Netahmad Syracuse University, S.I

109 Lenore Lane Centereach, N.Y. 11720 (516) 521-0488 [email protected] Twitter/Instagram: @journographica WASIMwww.wasimahmad.netAHMAD SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY, S.I. NEWHOUSE SCHOOL OF PUBLIC COMMUNICATIONS Education: M.S., Photography, concentration in photojournalism (2010) BINGHAMTON UNIVERSITY, HARPUR COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES B.A., English (2000 – 2004) SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY / SYRACUSE.EDU / SYRACUSE, NEW YORK Instructor, part time: Sept. 2015 – present • Teach online class in multimedia storytelling for Communications@Syracuse M.S. Program CANON USA / USA.CANON.COM / MELVILLE, NEW YORK Technical Specialist: Jan. 2015 – present • Create photography, DSLR and Cinema EOS trainings for internal, external audiences • Coordinate and teach internal and external photography workshops • Teach one-on-one sessions for Canon Live Learning Long Island program • Photograph in studio settings and on location for internal and social media use • Learn camera systems before release to public to create training documents • Study photography trends and train on competitors’ DSLRs to stay up-to-date on industry • Serve as public relations representative at industry trade shows (NAB, PhotoPlus, etc.) Experience: STONY BROOK UNIVERSITY / STONYBROOK.EDU/JOURNALISM / STONY BROOK, NEW YORK Assistant Professor of Multimedia, School of Journalism: Aug. 2009 – Jan. 2015 • Created and taught curriculum for web/social media/multimedia classes • Secured more than $75,000 photo/video equipment consignment from Nikon USA • Created, updated and maintained school’s -

Wallace House Journal

WALLACE HOUSE JOURNAL Fall 2018 Volume 29 | No. 1 The world’s gone mad! At least there’s Wallace House... and a royal baby! BY CATHERINE MACKIE ‘19 are still demanding a second referendum, while the Twitteratti, from both sides of the argument are still shouting a lot and putting eghan Markle is due to give birth in the Spring of 2019. their thoughts in capital letters to show HOW RIGHT THEY ARE. MHallelujah! I’m guessing I’m not alone in hoping the And if you don’t agree with me, THEN YOU’RE AN IDIOT. Queen’s eighth great-grandchild arrives in the world on March 29th. Ideally at around 11pm (GMT) because that’s the time the Which brings me to Donald Trump. No, stop it! I’m not calling the UK is scheduled to leave the European Union. If there’s one thing U.S. president an idiot. You’re taking me out of context! that’s guaranteed to give a brief respite to hours and hours of All I’m saying is that in coming to the U.S. for a year, I’ve moved hand-wringing, tediously repetitive arguments and media naval from a Brexit-obsessed media to a Trump-obsessed gazing, it’s a royal baby. media. I’m not arguing that what happens with Brexit I had hoped that coming to Ann Arbor would free me and Trump aren’t vitally important. Brexit is a key from the daily reports of EU “crisis talks” post-Brexit, moment in British modern political history. -

Syracuse University S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications Spring 2008 Vol. 20 No. 2 David Rubin in 1990, the Year He Became Dean of the Newhouse School

SyracuSe univerSity S.i. newhouSe School of Public communicationS SPring 2008 vol. 20 no. 2 David Rubin in 1990, the year he became dean of the Newhouse School. SyracuSe univerSity S.i. newhouSe School of Public communicationS SPring 2008 vol. 20 no. 2 Dean in this issue: David M. Rubin Dean’s Column 2 Executive Editor Wendy S. Loughlin G’95 New Dean Named 4 Editor Mirror Awards 5 Carol L. Boll Newhouse at Beijing 6 Contributors Jaime Winne Alvarez ’02 Student Protesters Remembered 7 Jim Baxter G’07, G’08 4 Aleta Burchyski G’08 Primary Coverage 8 Kathleen Haley ’92 Ashley Hanry ’04 Tully Award for Free Speech 8 Larry Kramer ’72 David Marc Learning by Doing 9 Jac’leen Smith G’08 Amy Speach New/Retiring Faculty 10 Photography Student Ambassadors 11 Steve Sartori Wendy S. Loughlin G’95 I-3 Center 12 Tony Golden 5 A Tribute to David Rubin 13 Graphic Design Elizabeth Percival Faculty Briefs 16 Assistant Dean of Student News 17 External Relations Lynn A. Vanderhoek ’89 Howard ’80 and Gail Campbell Woolley ’79 18 Office of External Eric Bress ’92 19 Relations 315-443-5711 8 Reflections from a Trailblazer 20 Web Site In Memoriam: Fred Dressler ’63 21 newhouse.syr.edu Newhouse Challenge 21 On the cover: Newspaper Design Awards 22 Dean David Rubin Class Notes 23 2 13 In the spring and summer of 1990, once I knew I was going to serve as the dean of the Newhouse School but before I arrived on campus, I tried to find something to read that would help me function as a dean. -

Capturing a Revolution Syracuse University S.I

SyracuSe univerSity S.i. newhouSe School of Public communicationS SPring 2011 vol. 23 no. 2 Capturing a revolution SyracuSe univerSity S.i. newhouSe School of Public communicationS SPring 2010 vol. 22 no. 2 Dean in this issue: Lorraine E. Branham Executive Editors Dean’s Column 1 Wendy S. Loughlin G’95 Kathleen M. Haley ’92 2011 Mirror Awards 2 Center for Digital Graphic Design Media Entrepreneurship 3 W. Michael McGrath First Toner Prize Awarded 4 Contributors International Experience 5 Jaime Winne Alvarez ’02 3 Carol L. Boll Photographic Excellence 6 Kate Morin ’11 Daniel Ellsberg 7 Valentina Palladino ’13 Cover: Egyptians Christy Perry take to the streets “CR-Z: You & Me” 8 Amanda Waltz G’11 of Cairo during the uprising earlier this The Best of Newspapers 9 Photography year in this photo On Assignment: Revolution 10 Daniel Barker ’11 shot by freelance Andrew Burton ’10 photojournalist SU Goes to South Africa 14 Andrew Burton ’10. Steve Davis Democracy in Action 16 Sean Harp ’11 Andrew Hida G’12 10 Professor Frank Biocca 18 Bob Miller G’11 Tron Legacy 19 Mackenzie Reiss ’11 Steve Sartori Let’s Talk 20 Assistant Dean of Focus on Refugees 22 External Relations The “Fox Kid” 23 Lynn A. Vanderhoek G’89 Covering the Capitol 24 Office of External Newhouse Guests 25 Relations 315-443-5711 Class Notes 26 20 Report of Donors 30 Web Site newhouse.syr.edu Facebook www.facebook.com/NewhouseSU Twitter @NewhouseSU 2 26 The Public’s Right to Know Forty years ago this spring, the Pentagon Papers hit materials involving the war dispatches. -

Curriculum Vitae 22Feb19

Curriculum Vitae Simon Perez Assistant Professor S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications Syracuse University 215 University Place, Syracuse, NY 13244 315 443 9253 [email protected] Education Universidad Complutense Madrid, Spain Master of Professional Journalism Washington and Lee University Lexington, Virginia Bachelor of Arts in Journalism Academic Assistant Professor – Broadcast and Digital Journalism Department experience S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications, Syracuse University August 2011 to present Courses taught: Television News Reporting, BDJ 664, BDJ 464: Graduate and undergraduate level students learn how to produce quality television news stories by defining what distinguishes a good news story, locating reliable information, applying ethical principles and understanding the impact of diversity in the newsgathering process. Long-form Television Reporting, BDJ MIL 530: The military students add to their proficiency in technical skills by learning how to tell long-form stories, which demand more time and go into more depth than those found in regularly scheduled news broadcasts. Planning and organization are key features of this course, so the final stories reflect a more thorough level of reporting. Television News Producing and Anchoring, BDJ 465: Undergraduate students learn how to use news judgment, news writing, reporting, shooting and editing skills to assemble a newscast, paying particular attention to the demands and leadership responsibilities of the producer. The students also work on their on-camera presentation skills as anchors. Broadcast/Digital News Writing, BDJ 311: The focus of this undergraduate course is on writing deadline stories for radio and the web and, by the end of the course, the basics of television news writing. -

Les Rose Complete CV 2021

LES ROSE Professor of Practice S.I. Newhouse School, Syracuse University Broadcast and Digital Journalism 215 University Place, Newhouse 2-376 Syracuse, NY 13210 213-999-5516 (cell) [email protected] [email protected] www.lesroseonline.com @LesRoseSyracuse Since the Fall of 2016, I have served as a Professor of Practice at the S.I. Newhouse School at Syracuse University, in Broadcast and Digital Journalism. My duties include teaching at least three classes per semester, mentoring students, helping students get their first jobs through industry contacts, service to the University, community, and service to the TV News photojournalism industry, which I represent to the school. For 38 years, I was a television news photojournalist/field producer/video editor/ live truck operator. For 22 years, I was a photojournalist/field producer for CBS National News, Los Angeles Bureau. During that time I worked with Steve Hartman in Everybody Has a Story, Assignment America, 60 Minutes 2, and On the Road with Steve Hartman. I have been awarded five Emmy Awards, one National Peabody Award, and one National Edward R. Murrow. Since 1998, I have taught seminars across the United States and in five countries for professionals, college and high school students. EDUCATION Master of Arts, Broadcast Journalism, 2010 University of Nebraska, Lincoln Bachelor of Arts, Broadcast Journalism, 1979 University of South Florida, Tampa Minor: American History ACADEMIC HONORS AND AWARDS 2011 University Libraries Influence Award Winner, University of Nebraska, for Influence of Thesis: Edward R. Murrow’s Ethics and Influence 2010 and 2011 Most Downloaded Thesis for the University of Nebraska Library2000 Alumni of the Year, Mass Communications Department, University of South Florida 1 PROFESSIONAL HONORS AND AWARDS 2015 Edward R. -

Syracuse University S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications Spring 2013 Vol

SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY S.I. NEWHOUSE SCHOOL OF PUBLIC COMMUNICATIONS SPRING 2013 VOL. 25 NO.2 SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY S.I. NEWHOUSE SCHOOL OF PUBLIC COMMUNICATIONS SPRING 2013 VOL. 25 NO. 2 IN THIS ISSUE: Dean’s Column 1 Dick Clark Studios 2 Dean Lorraine E. Branham Mirror Award Winners 5 Harnessing Big Data 6 Executive Editor Wendy S. Loughlin G’95 Students Win at Telly Awards 9 Student Film Project Partnership 9 Editor 10 Kathleen M. Haley ’92 Toner Prize 10 Graphic Design Bright Future for Journalists 10 Elizabeth Percival Acclaimed Photographer Joins Faculty 11 Contributors Finding Entrepreneurial Success 12 Elina Berzins ’13 Student App Looks at CNY Winters 18 Debbie Letchman Fachler ’13 Ruth Li G’13 Student Startup Madness 19 Parade of Speakers 2o Photography 18 Alyssa Greenberg ’13 Interning with Charles Barkley 22 Steve Sartori Alexia Awards 22 Marina Zarya ’11, G’12 Class Notes 23 Assistant Dean of External Relations Report of Donors 24 Lynn A. Vanderhoek G’89 Office of External Relations 315-443-5711 Website newhouse.syr.edu 20 Facebook www.facebook.com/NewhouseSU Twitter @NewhouseSU On the cover: artist’s rendering of the renovated Newhouse 2 atrium 2 22 Communications in the 21st Century: The Great Balancing act Last spring, the Newhouse School honored Molly Ball, Alliance, which will support the creation of a digital a staff writer at The Atlantic, with the Toner Prize for advertising program at Newhouse. Alumnus Peter Horvitz Excellence in Political Reporting. The prize is named for ’76 endowed our chair in journalism innovation with the the late Robin Toner, first female political correspondent intention of allowing students to explore the intersection for The New York Times and, we are proud to say, a of journalism and technology, and to work collaboratively Newhouse alumna.