Bill Birnbauer Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steering Committee

Steering Committee Steven Aftergood Federation of American Scientists Coalition Activities 21 July 2010 – 20 October 2010 Bill Allison Sunlight Foundation OTG engages in a variety of campaigns initiated by coalition staff, and by other partners Mary Alice Baish American Association themselves. Most of what the staff does is in coordination with partners and with others of Law Libraries outside the coalition. We are regularly asked to coordinate other groups and to identify Gary Bass* OMB Watch possible partners for campaigns. Tom Blanton* Advance the right-to-know at the federal and state levels through legislative National Security Archive and other vehicles/ Strengthen coordination and engagement of organizations Danielle Brian currently working on right to know and anti-secrecy issues Project on Government Oversight Promote and Sustain Openness and Transparency/ Promote a Culture of Openness in Government Lucy Dalglish Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Open Government Directive/Open Government Plans Press The coalition has continued monitoring and measuring federal agencies' progress Charles Davis National Freedom of toward fulfilling President Obama’s commitment to “creating an unprecedented level of Information Coalition openness in Government." Results of re-evaluations of open government plans that Leslie Harris were updated between their initial release and June 25, and updated audit results were Center for Democracy & Technology posted to the coalition’s Open Government Plans Audit site Robert Leger (http://sites.google.com/site/opengovtplans/) in July. Society of Professional Journalists Conrad Martin The updated results also include evaluations of plans produced by entities that were not Fund for Constitutional Government required to produce plans, but did so anyway. -

Journalism in Jordan: a Comparative Analysis of Press Freedom in the Post-Arab Spring Environment

Global Media Journal ISSN: 1550-7521 Special Issue 2015 Journalism in Jordan: A comparative analysis of press freedom in the post-Arab spring environment Matt J. Duffy, Hadil Maarouf 1. PhD, Berry College, GA,USA 2. Center for International Media Education, Georgia State University Corresponding author: Matt J. Duffy, PhD, Berry College, GA,USA. E-mail: [email protected] 1. Abstract Although once known for one of the most vibrant media sectors in the Arab world, the press freedom ranking of Jordan has declined in recent years. Despite governmental assurances during the height of the Arab Spring, promised reforms in freedom of the press have failed to materialize. By studying primary and secondary sources and interviewing Jordanian journalists, the authors identify four main developments that show diminished press freedom in Jordan. These developments will be described in detail and examined in the context of international media law. The analysis finds that the Jordanian approach to media regulation is often at odds with the approach recommended by the United Nations free speech rapporteurs. The authors also examine the press system of Jordan through the lens of Ostini and Fung’s press system theory. 1 Global Media Journal ISSN: 1550-7521 Special Issue 2015 2. Introduction organizations support the observation As the Arab region erupted in protests in that press freedom has gotten worse in early 2011, the king of Jordan appeared Jordan (see figures 1 and 2.) to see the writing on the wall. He fired Figure 1: Freedom House his cabinet and called for immediate changes in the organization of his Press Freedom Ranking government. -

Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia

Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia Geographically, Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam are situated in the fastest growing region in the world, positioned alongside the dynamic economies of neighboring China and Thailand. Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia compares the postwar political economies of these three countries in the context of their individual and collective impact on recent efforts at regional integration. Based on research carried out over three decades, Ronald Bruce St John highlights the different paths to reform taken by these countries and the effect this has had on regional plans for economic development. Through its comparative analysis of the reforms implemented by Cam- bodia, Laos and Vietnam over the last 30 years, the book draws attention to parallel themes of continuity and change. St John discusses how these countries have demonstrated related characteristics whilst at the same time making different modifications in order to exploit the strengths of their individual cultures. The book contributes to the contemporary debate over the role of democratic reform in promoting economic devel- opment and provides academics with a unique insight into the political economies of three countries at the heart of Southeast Asia. Ronald Bruce St John earned a Ph.D. in International Relations at the University of Denver before serving as a military intelligence officer in Vietnam. He is now an independent scholar and has published more than 300 books, articles and reviews with a focus on Southeast Asia, -

Realism, Photography and Journalistic Objectivity in 19Th Century America

Studies in Visual Communication Volume 4 Issue 2 Winter 1977 Article 5 1977 Realism, Photography and Journalistic Objectivity in 19th Century America Dan Schiller Recommended Citation Schiller, D. (1977). Realism, Photography and Journalistic Objectivity in 19th Century America. 4 (2), 86-98. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/svc/vol4/iss2/5 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/svc/vol4/iss2/5 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Realism, Photography and Journalistic Objectivity in 19th Century America This contents is available in Studies in Visual Communication: https://repository.upenn.edu/svc/vol4/iss2/5 the whole field of 19th century painterly and literary art. The key assumption of photographic realism-that precisely accurate and complete copies of reality could be produced from symbolic materials-was rather freely translated across numerous visual and verbal codes, and not only within the REALISM, PHOTOGRAPHY accepted realm of art. After first explicating the general sig AND JOURNALISTIC OBJECTIVITY nificance of this increasingly ubiquitous assumption, I will IN 19th CENTURY AMERICA tentatively explore some of its consequences for literature and for journalism. DAN SCHILLER A JOUST WITH "REALISM" When we commend a work of art as being "realistic," we Hostile critics often choose to equate realism per se with commonly mean that it succeeds at faithfully copying events the demonstration of a few apparently basic qualities in or conditions in the "real" world. How can we believe that works of art. Foremost among these is "objectivity." Wellek pictures and writings can be made so as to copy, truly and (1963 :253), for example, defines realism as "the objective accurately, a "natural" reality? The search for an answer to representation of contemporary social reality." Hemmings this deceptively simple question motivates the present essay. -

![Defamation Bill [HL], 127 of 1995-96: Law and Procedure](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1549/defamation-bill-hl-127-of-1995-96-law-and-procedure-161549.webp)

Defamation Bill [HL], 127 of 1995-96: Law and Procedure

Defamation Bill [HL], Bill 127 of 1995-96: Law and Procedure Research Paper 96/60 16 May 1996 This paper seeks to give a brief outline of the law of defamation and to explain the main provisions of the Defamation Bill [HL] which is due to have its Second Reading on 21 May 1996. Although the paper deals mainly with the changes proposed to law and procedure in England and Wales it is pointed out where the changes affect Scotland and Northern Ireland. This paper should be read in conjuction with Research Paper 96/61 which discusses parliamentary privilege in the context of the law of defamation and the interpretation of 'proceedings in Parliament'. Helena Jeffs Home Affairs Section House of Commons Library Summary The Defamation Bill [HL] is intended to "simplify this complex area of law and procedure, and fit well with current developments in the conduct of civil litigation generally".1 In brief the Bill seeks to introduce the following amendments to the law and procedure in actions for defamation: a new statutory defence to supersede the common law defence of innocent dissemination and to concentrate on the concept of responsibility for publication a new and more streamlined defence of unintentional defamation which would be available to a defendant who is willing to make an 'offer of amends' (ie to pay compensation assessed by a judge and to publish an appropriate correction and apology) a one-year limitation period for actions for libel, slander or malicious falsehood a new fast-track offer of amends procedure intended to provide a prompt and inexpensive remedy in less serious defamation cases new powers for judges enabling them to dispose of a claim summarily and to grant damages of up to £10,000 There has long been consensus on the need for reform of defamation law and procedure, particularly in view of certain high awards of damages by juries and the high costs of proceedings. -

How to Fund Investigative Journalism Insights from the Field and Its Key Donors Imprint

EDITION DW AKADEMIE | 2019 How to fund investigative journalism Insights from the field and its key donors Imprint PUBLISHER RESPONSIBLE PUBLISHED Deutsche Welle Jan Lublinski September 2019 53110 Bonn Carsten von Nahmen Germany © DW Akademie EDITORS AUTHOR Petra Aldenrath Sameer Padania Nadine Jurrat How to fund investigative journalism Insights from the field and its key donors Sameer Padania ABOUT THE REPORT About the report This report is designed to give funders a succinct and accessible introduction to the practice of funding investigative journalism around the world, via major contemporary debates, trends and challenges in the field. It is part of a series from DW Akademie looking at practices, challenges and futures of investigative journalism (IJ) around the world. The paper is intended as a stepping stone, or a springboard, for those who know little about investigative journalism, but who would like to know more. It is not a defense, a mapping or a history of the field, either globally or regionally; nor is it a description of or guide to how to conduct investigations or an examination of investigative techniques. These are widely available in other areas and (to some extent) in other languages already. Rooted in 17 in-depth expert interviews and wide-ranging desk research, this report sets out big-picture challenges and oppor- tunities facing the IJ field both in general, and in specific regions of the world. It provides donors with an overview of the main ways this often precarious field is financed in newsrooms and units large and small. Finally it provides high-level practical ad- vice — from experienced donors and the IJ field — to help new, prospective or curious donors to the field to find out how to get started, and what is important to do, and not to do. -

An End Run Around the First Amendment: „Libel Tourists‟ Take Aim Overseas

An End Run Around the First Amendment: „Libel Tourists‟ Take Aim Overseas By Ryan Feeney 2008 Pulliam Kilgore Intern Bruce W. Sanford Bruce D. Brown Laurie A. Babinski BAKER & HOSTETLER LLP Washington, D.C. Counsel to the Society of Professional Journalists September 2008 In the throes of the American Civil Rights movement as Southern blacks flexed their political might against segregation, a city commissioner in Alabama sued the country‟s most prominent newspaper, The New York Times. L.B. Sullivan‟s libel suit sought to silence the implication of his critics that he was part of a racist Southern oligarchy responsible for the violent suppression of black protests in Montgomery. It failed, and an uniquely American brand of free speech was born. In deciding that landmark free-speech case, New York Times v. Sullivan, 1 the U.S. Supreme Court noted how libel suits such as Sullivan‟s threatened “the very existence of an American press virile enough to publish unpopular views on public affairs.” Throughout modern American history, linking a person to an unpopular group has often led to a rash of libel suits against the press. It happened with communism in the 1940s, organized crime in the 1970s, and homosexuality in the 1980s under the stigmatizing glare of the AIDS epidemic. Yet in the more than four decades since the New York Times decision, American libel plaintiffs have found it acutely difficult to muzzle the press. But these free speech protections apply only on American soil, which means they cannot be used against the latest wave of libel litigants who bring suits overseas – foreigners accused of terrorism ties. -

The Problem of Trans-National Libel, 60 Am

University of Miami Law School University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository Articles Faculty and Deans 2012 The rP oblem of Trans-National Libel Lili Levi University of Miami School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/fac_articles Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, and the Jurisdiction Commons Recommended Citation Lili Levi, The Problem of Trans-National Libel, 60 Am. J. Comp. L. 507 (2012). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty and Deans at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LILI LEVI* The Problem of Trans-National Libelt Forum shopping in trans-nationallibel cases-"libel tourism"- has a chilling effect on journalism, academic scholarship,and scien- tific criticism. The United States and Britain (the most popular venue for such cases) have recently attempted to address the issue legisla- tively. In 2010, the United States passed the SPEECH Act, which prohibits recognition and enforcement of libel judgments from juris- dictions applying law less speech-protective than the First Amendment. In Britain, consultation has closed and the Parliamen- tary Joint Committee has issued its report on a broad-ranginglibel reform bill proposed by the Government in March 2011. This Article questions the extent to which the SPEECH Act and the Draft Defama- tion Bill will accomplish their stated aims. -

DIVERSE EQUITABLE INCLUSIVE K-12 Public Schools a New Call for Philanthropic Support

DIVERSE EQUITABLE INCLUSIVE K-12 Public Schools A New Call for Philanthropic Support the Sillerman Center FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF PHILANTHROPY Acknowledgements This report was written by Dr. Susan Eaton and Dr. Suchi Saxena. This report grows out of a long-running project of the Sillerman Center that engages grantmakers who want to better understand the causes, myriad harms and potential cures for racial and socioeconomic segregation in our nation's K-12 public schools. This report was informed by interviews with a wide variety of educators and other practitioners working towards diverse, equitable and inclusive schools, by numerous convenings and conferences, by research and by the authors' experience in this field. We wish to thank our project collabora- tors and sponsors, The Ford Foundation and the Einhorn Family Charitable Trust. We deeply appreciate all the people who reviewed this report for us, who participated in interviews and who attended meetings that we hosted in 2017. Special thanks to Sheryl Seller, Stacey King, Amber Abernathy and Victoria St. Jean at the Sillerman Center, to Mary Pettigrew, who designed this report and our beloved proofreader, Kelly Garvin. We especially appreciate the thorough reviews from Gina Chirichigno, Itai Dinour, Sanjiv Rao and Melissa Johnson Hewitt, whose suggestions greatly improved this report. Susan E. Eaton Director, The Sillerman Center for the Advancement of Philanthropy Professor of Practice in Social Policy The Heller School for Social Policy and Management Brandeis University Table of -

360° Brand Engagement Presented by Munson Steed • (404) 635-1313 Ext

360° Brand Engagement Presented by Munson Steed • (404) 635-1313 ext. 113 • [email protected] Steed Media Is… DIGITAL PRINT •… a multimedia powerhouse with national reach. •…a year-round print presence in 19 of the top 25 urban DMAs •…a specialist in localization and nationalization, thanks to our network of city managers MOBILE SOCIAL •…an ideal urban marketing extension specializing in 360 degree integration and partnerships What Steed Media does… CUSTOM VIDEO ON • Custom publications PUBLISHING & DEMAND •Editorial Development INTEGRATION • Direct consumer engagement opportunities • Public Relations •Marketing and Brand Strategy •Content Propagation PHOTO & •Facilitation of app, software and technology EVENTS VIDEO development SERVICES •On-Demand cable exposure • Custom microsite design and management • Television production •We turn ideas into profits! A M E D I A A N D BRANDING SOLUTION 360° Degree Integrated Engagement of the Urban Consumer Print The nation’s largest chain of African-American newspapers, in 19 of the Top 25 AA markets. Events/Promotions Aimed at producing brand-engagement experiences, onsite activations and purchase activities. Digital Original content that rides the pulse of Urban America. Mobile Site Keeping Urban America’s lifestyle elements at their fingertips…even on the go Custom Publications Using the power of relevance to drive brand consideration. Video On Demand Harnessing the power of an engaged audience. A M E D I A A N D BRANDING SOLUTION Audience Demographics A M E D I A A N D BRANDING SOLUTION Print At nearly 40 million, the African- American population represents more than 13% of the U.S. population, is growing faster than the general population, and is experiencing faster income growth than the rest of the population. -

2015-16-Syracuse-Team-Report-And

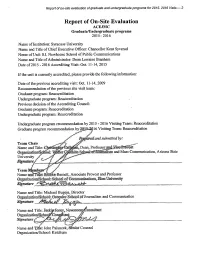

PART I: General information Name of Institution: Syracuse University Name of Unit: S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications Year of Visit: 2015 Executive Summary: • The School’s skills courses comply with the ACEJMC mandate of no more than 20 students per section. • The Newhouse School’s Mission Statement is a part of its Strategic Plan, which is written to cover all academic programs in the School. It reinforces the School’s commitment to graduating communication leaders with a solid liberal arts foundation. Graduate students are selected in keeping with this mandate; the vast majority of them come to the School with baccalaureate education that has a focus on the liberal arts. Their rigorous professional Master’s education is designed in part to build from that liberal arts foundation. From there, the mandate that we graduate leaders who are agile, ethically responsible, who embrace diversity and who can demonstrate cutting-edge skill requires the Professional Master’s programs to concentrate uniquely rigorous activities into their shorter and more intense time frames. 1. Check regional association by which the institution now is accredited. X Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools _ New England Association of Schools and Colleges _ North Central Association of Colleges and Schools _ Northwest Association of Schools and Colleges _ Southern Association of Colleges and Schools _ Western Association of Schools and Colleges 2. Indicate the institution’s type of control; check more than one if necessary. X Private _ Public _ Other (specify) Report of on-site evaluation of graduate and undergraduate programs for 2015- 2016 Visits — 2 3. -

First Quarterly Report: January-March, 2012

mCÄmNÐlÉkßrkm<úCa Documentation Center of Cambodia Quarterly Report: January‐March, 2012 DC‐Cam Team Leaders and the Management Team Prepared and Compiled by Farina So Office Manager Edited by Norman (Sambath) Pentelovitch April, 2012 Sirik Savina, Outreach Coordinator, discusses with the villagers about the hearing process at Khmer Rouge Tribunal. Abbreviations CHRAC Cambodian Human Rights Action Committee CP Civil Party CTM Cambodia Tribunal Monitor DC‐Cam Documentation Center of Cambodia DK Democratic Kampuchea ECCC Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia ICC International Criminal Court ITP Sida Advanced International Training Programme KID Khmer Institute for Democracy KR Khmer Rouge MMMF Margaret McNamara Memorial Fund MRDC Mondul Kiri Resource and Documentation Centre OCP Office of Co‐Prosecutors OCIJ Office of Co‐Investigating Judges PTSD Post‐Traumatic Stress Disorder Sida Swedish International Development Agency TSL Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum UN United Nations UNDP United Nation for Development Program USAID United States Agency for International Development VOT Victims of Torture VPA Victims Participation Project VSS Victim Support Section YFP Youth for Peace YRDP Youth Resource Development Program 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary.............................................................................................................. 1 Results/Outcome................................................................................................................. 7 Raised Public Awareness on the Value of Documents.............................................