Defamation Bill [HL], 127 of 1995-96: Law and Procedure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steering Committee

Steering Committee Steven Aftergood Federation of American Scientists Coalition Activities 21 July 2010 – 20 October 2010 Bill Allison Sunlight Foundation OTG engages in a variety of campaigns initiated by coalition staff, and by other partners Mary Alice Baish American Association themselves. Most of what the staff does is in coordination with partners and with others of Law Libraries outside the coalition. We are regularly asked to coordinate other groups and to identify Gary Bass* OMB Watch possible partners for campaigns. Tom Blanton* Advance the right-to-know at the federal and state levels through legislative National Security Archive and other vehicles/ Strengthen coordination and engagement of organizations Danielle Brian currently working on right to know and anti-secrecy issues Project on Government Oversight Promote and Sustain Openness and Transparency/ Promote a Culture of Openness in Government Lucy Dalglish Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Open Government Directive/Open Government Plans Press The coalition has continued monitoring and measuring federal agencies' progress Charles Davis National Freedom of toward fulfilling President Obama’s commitment to “creating an unprecedented level of Information Coalition openness in Government." Results of re-evaluations of open government plans that Leslie Harris were updated between their initial release and June 25, and updated audit results were Center for Democracy & Technology posted to the coalition’s Open Government Plans Audit site Robert Leger (http://sites.google.com/site/opengovtplans/) in July. Society of Professional Journalists Conrad Martin The updated results also include evaluations of plans produced by entities that were not Fund for Constitutional Government required to produce plans, but did so anyway. -

Realism, Photography and Journalistic Objectivity in 19Th Century America

Studies in Visual Communication Volume 4 Issue 2 Winter 1977 Article 5 1977 Realism, Photography and Journalistic Objectivity in 19th Century America Dan Schiller Recommended Citation Schiller, D. (1977). Realism, Photography and Journalistic Objectivity in 19th Century America. 4 (2), 86-98. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/svc/vol4/iss2/5 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/svc/vol4/iss2/5 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Realism, Photography and Journalistic Objectivity in 19th Century America This contents is available in Studies in Visual Communication: https://repository.upenn.edu/svc/vol4/iss2/5 the whole field of 19th century painterly and literary art. The key assumption of photographic realism-that precisely accurate and complete copies of reality could be produced from symbolic materials-was rather freely translated across numerous visual and verbal codes, and not only within the REALISM, PHOTOGRAPHY accepted realm of art. After first explicating the general sig AND JOURNALISTIC OBJECTIVITY nificance of this increasingly ubiquitous assumption, I will IN 19th CENTURY AMERICA tentatively explore some of its consequences for literature and for journalism. DAN SCHILLER A JOUST WITH "REALISM" When we commend a work of art as being "realistic," we Hostile critics often choose to equate realism per se with commonly mean that it succeeds at faithfully copying events the demonstration of a few apparently basic qualities in or conditions in the "real" world. How can we believe that works of art. Foremost among these is "objectivity." Wellek pictures and writings can be made so as to copy, truly and (1963 :253), for example, defines realism as "the objective accurately, a "natural" reality? The search for an answer to representation of contemporary social reality." Hemmings this deceptively simple question motivates the present essay. -

Annotated Bibliography

Annotated Bibliography Primary Sources Ang, Tom. Photography: the Definitive Visual History. DK Publishing, 2014. This primary source provides me with information on Lewis Hine. Lewis Hine had skills of a great photographer. His photography made an impact on child labor laws. Hine was a muckraker, for he went undercover having people take photographic surveys of child labor from 1908 to 1918. “A Photograph of a Settlement House Kindergarten in Chicago, Illinois, 1901.” A Photograph of a Settlement House Kindergarten in Chicago, Illinois, 1901. | DPLA, dp.la/primary-source-sets/settlement-houses-in-the-progressive-era/sources/1168. This picture was used for a title background. It is a picture of a settlement house. Augustine, Jackie. “The Original Kodak Moment: Snapshots Taken from the Camera That Changed Photography in 1888.” The Imaging Alliance, The Imaging Alliance, 1 Oct. 2013, www.theimagingalliance.com/the-original-kodak-moment-snapshots-taken-from-the-camer a-that-changed-photography-in-1888/. I used the photo of a Kodak camera from this site for a title background. Bellis, Mary. “The History of Kodak: How Rolled Film Made Everyone a Photographer.” ThoughtCo, ThoughtCo, 5 Oct. 2019, www.thoughtco.com/george-eastman-history-of-kodak-1991619. The Kodak camera had different settings. This website includes information from the original Kodak Manual. There were certain ways to use the camera, as for a camera nowadays. Just like a professional camera now, the kodak had settings for exposure. Durkin, Erin. “Women's March 2019: Thousands to Protest across US.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 19 Jan. 2019, www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/jan/19/womens-march-2019-protests-latest-event. -

N Ieman Reports

NIEMAN REPORTS Nieman Reports One Francis Avenue Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 Nieman Reports THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY VOL. 62 NO. 1 SPRING 2008 VOL. 62 NO. 1 SPRING 2008 21 ST CENTURY MUCKRAKERS THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION HARVARDAT UNIVERSITY 21st Century Muckrakers Who Are They? How Do They Do Their Work? Words & Reflections: Secrets, Sources and Silencing Watchdogs Journalism 2.0 End Note went to the Carnegie Endowment in New York but of the Oakland Tribune, and Maynard was throw- found times to return to Cambridge—like many, ing out questions fast and furiously about my civil I had “withdrawal symptoms” after my Harvard rights coverage. I realized my interview was lasting ‘to promote and elevate the year—and would meet with Tenney. She came to longer than most, and I wondered, “Is he trying to my wedding in Toronto in 1984, and we tried to knock me out of competition?” Then I happened to keep in touch regularly. Several of our class, Peggy glance over at Tenney and got the only smile from standards of journalism’ Simpson, Peggy Engel, Kat Harting, and Nancy the group—and a warm, welcoming one it was. I Day visited Tenney in her assisted living facility felt calmer. Finally, when the interview ended, I in Cambridge some years ago, during a Nieman am happy to say, Maynard leaped out of his chair reunion. She cared little about her own problems and hugged me. Agnes Wahl Nieman and was always interested in others. Curator Jim Tenney was a unique woman, and I thoroughly Thomson was the public and intellectual face of enjoyed her friendship. -

Muckraker Project.Pdf

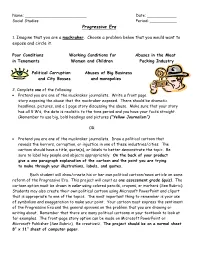

Name: _________________________ Date: ____________ Social Studies Period: ___________ Progressive Era 1. Imagine that you are a muckraker. Choose a problem below that you would want to expose and circle it. Poor Conditions Working Conditions for Abuses in the Meat in Tenements Women and Children Packing Industry Political Corruption Abuses of Big Business and City Bosses and monopolies 2. Complete one of the following: • Pretend you are one of the muckraker journalists. Write a front page story exposing the abuse that the muckraker exposed. There should be dramatic headlines, pictures, and a 1 page story discussing the abuse. Make sure that your story has all 5 W’s, the date is realistic to the time period and you have your facts straight. (Remember to use big, bold headings and pictures (“Yellow Journalism”) OR • Pretend you are one of the muckraker journalists. Draw a political cartoon that reveals the horrors, corruption, or injustice in one of these industries/cities. The cartoon should have a title, quote(s), or labels to better demonstrate the topic. Be sure to label key people and objects appropriately. On the back of your product give a one paragraph explanation of the cartoon and the point you are trying to make through your illustrations, labels, and quotes. Each student will draw/create his or her own political cartoon/news article on some reform of the Progressive Era. This project will count as one assessment grade (quiz). The cartoon option must be drawn in color using colored pencils, crayons, or markers (See Rubric). Students may also create their own political cartoon using Microsoft PowerPoint and clipart that is appropriate to one of the topics. -

Iighiing Words T', FIGHTING WORDS

iighiing words t', FIGHTING WORDS HGHTING WORDS • Selections from twenty-five years of The Daily Worker New Century Publishers • New York • 1949 Copyright by NEW CENTURY PUBLISHERS, 832 Broadway, New York 3, New York FBINTED m V.8.A. CONTENTS PREFACE xi REMEMBER WHEN? EVENTS THAT MADE HISTORY. 1924 to 1949 THE DEATH OF V. I. LENIN 3 Mourners Pass Bier of V. I. Lenin 3 'Gene Debs Pays Glowing Tribute 4 SACCO AND VAN2ETTI 4 Boston Prepares for a Lynching, by Michael Gold 4 Sacco and Vanzetti Murdered 6 THE GREAT DEPRESSION 8 A Signal of Coming Struggle, Editorial 8 Jobless Demand Relief 10 The Hunger March 11 Hoover Ignores Hunger Marchers 13 Police Gas Bonus March 15 THE SCOTTSBORO CASE 17 Ruby Bates Denies Rape 17 "Why I Fled Prison," by Haywood Patterson 19 HERNDON GETS 20 YEARS ON CHAIN GANG, by R. H. Hart 20 THE REICHSTAG FIRE FRAME-UP 21 DinutroflF Shatters Frame^Up. ■.. ."7.~ 21 Unmasked by Dimitroff 22 SIT DOWNI by George Morris 23 SPAIN IN ARMS 26 In Madrid, by Robert Minor 26 Crossing the Ebro, by Joseph North 27 V THE MUNICH BETRAYAL 30 The Betrayal, Editorial by Harry Cannes 30 Three Years After, Editorial 32 TOM MOONEY S3 Tom Mooney Freed, by Al Richmond 33 The Most Celebrated Case of All Time, by Robert Minor 34 NAZIS INVADE U.S.S.R 37 Peqale Rally to Stalin 88 PEARL HARBOR, Editorial 40 STALINGRAD, by Veteran Commander 42 D-DAY 44 Rendezvous in Berlin, by Ilya Ehrenburg 45 I THE COMMUNIST PARTY 46 Foster Calls for Return to Party 47 Parley Reestablishes Party 47 Dreiser Joins the Communist Party 48 LYNCH TERROR NORTH AND SOUTH 50 Taps in Freeport, by Harry Raymond 50 Columbia, Tennessee, by Harry Raymond 52 FIGHTING JIM GROW IN SPORTS 54 Paige Asks Chance for Negro Stars, by Lester Rodney 55 "Robinson's a Dodger," the Guy Said, by Bill Mardo 56 GAMBLING WITH MINERS' LIVES, by Ruby Cooper 57 THE MARSHALL PLAN 59 The Ruhr—Can Liberals Support Revival of Reich Trusts? by Milton Howard,. -

What Is a Muckraker? (PDF, 67

What Is a Muckraker? President Theodore Roosevelt popularized the term muckrakers in a 1907 speech. The muckraker was a man in John Bunyan’s 1678 allegory Pilgrim’s Progress who was too busy raking through barnyard filth to look up and accept a crown of salvation. Though Roosevelt probably meant to include “mud-slinging” politicians who attacked others’ moral character rather than debating their ideas, the term has stuck as a reference to journalists who investigate wrongdoing by the rich or powerful. Historical Significance In its narrowest sense, the term refers to long-form, investigative journalism published in magazines between 1900 and World War I. Unlike yellow journalism, the reporters and editors of this period valued accuracy and the aggressive pursuit of information, often by searching through mounds of documents and data and by conducting extensive interviews. It sometimes included first- person reporting. Muckraking was seen in action when Ida M. Tarbell exposed the strong-armed practices of the Standard Oil Company in a 19-part series in McClure’s Magazine between 1902 and 1904. Her exposé helped end the company’s monopoly over the oil industry. Her stories include information from thousands of documents from across the nation as well as interviews with current and former executives, competitors, government regulators, antitrust lawyers and academic experts. It was republished as “The Rise of the Standard Oil Company.” Upton Sinclair’s investigation of the meatpacking industry gave rise to at least two significant federal laws, the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act. Sinclair spent seven weeks as a worker at a Chicago meatpacking plant and another four months investigating the industry, then published a fictional work based on his findings as serial from February to November of 1905 in a socialist magazine. -

A Muckraker's Aftermath: the Jungle of Meat-Packing Regulation After A

William Mitchell Law Review Volume 27 | Issue 4 Article 1 2001 A Muckraker's Aftermath: The unJ gle of Meat- packing Regulation after a Century Roger I. Roots Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr Recommended Citation Roots, Roger I. (2001) "A Muckraker's Aftermath: The unJ gle of Meat-packing Regulation after a Century," William Mitchell Law Review: Vol. 27: Iss. 4, Article 1. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol27/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in William Mitchell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Roots: A Muckraker's Aftermath: The Jungle of Meat-packing Regulation af A MUCKRAKER'S AFTERMATH: THEJUNGLE OF MEAT-PACKING REGULATION AFTER A CENTURY Roger Rootst I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................... 2413 II. T HEJUNGLE ......................................................................... 2415 III. WHAT WAS DONE ................................................................. 2419 IV. THE MICROSCOPIC WORLD ESCAPES CONTROL ................... 2426 V . CO NCLUSION ........................................................................ 2433 I. INTRODUCTION If Harriet Beecher Stowe can be blamed for the Civil War,' then Upton Sinclair must be blamed for the entirety of the gov- ernment's interdiction into American meat quality regulation dur- ing the twentieth century.2 Sinclair's novel The Jungle-set amid the wretched working conditions of Chicago's meat packing plants at the turn of the century-created an immense populist eruption in 1906, and led directly to passage of federal meat inspection laws3 t Roger Isaac Roots graduated from Roger Williams University School of Law in 1999 and Montana University-Billings (B.S. -

Kennedy-Chapter 01

PART FOUR FORGING AN INDUSTRIAL SOCIETY ᇻᇾᇻ 1865–1899 nation of farmers fought the Civil War in the authority was invoked to regulate the use of natural A 1860s. By the time the Spanish-American War resources. The rise of powerful monopolies called into broke out in 1898, America was an industrial nation. question the government’s traditional hands-off pol- For generations Americans had plunged into the icy toward business, and a growing band of reformers wilderness and plowed their fields. Now they settled increasingly clamored for government regulation of in cities and toiled in factories. Between the Civil private enterprise. The mushrooming cities, with their War and the century’s end, economic and techno- needs for transport systems, schools, hospitals, sani- logical change came so swiftly and massively that it tation, and fire and police protection, required bigger seemed to many Americans that a whole new civi- governments and budgets than an earlier generation lization had emerged. could have imagined. As never before, Americans In some ways it had. The sheer scale of the new struggled to adapt old ideals of private autonomy to industrial civilization was dazzling. Transcontinen- the new realities of industrial civilization. tal railroads knit the country together from sea to With economic change came social and politi- sea. New industries like oil and steel grew to stag- cal turmoil. Labor violence brought bloodshed to gering size—and made megamillionaires out of places such as Chicago and Homestead, Pennsylva- entrepreneurs like oilman John D. Rockefeller and nia. Small farmers, squeezed by debt and foreign steel maker Andrew Carnegie. -

IN SULLIVAN's SHADOW: the USE and ABUSE of LIBEL LAW DURING the CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT a Dissertation Presented to the Facult

IN SULLIVAN’S SHADOW: THE USE AND ABUSE OF LIBEL LAW DURING THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by AIMEE EDMONDSON Dr. Earnest L. Perry Jr., Dissertation Supervisor DECEMBER 2008 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled: IN SULLIVAN’S SHADOW: THE USE AND ABUSE OF LIBEL LAW DURING THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT presented by Aimee Edmondson, a candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. ________________________________ Associate Professor Earnest L. Perry Jr. ________________________________ Professor Richard C. Reuben ________________________________ Associate Professor Carol Anderson ________________________________ Associate Professor Charles N. Davis ________________________________ Assistant Professor Yong Volz In loving memory of my father, Ned Edmondson ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It would be impossible to thank everyone responsible for this work, but special thanks should go to Dr. Earnest L. Perry, Jr., who introduced me to a new world and helped me explore it. I could not have asked for a better mentor. I also must acknowledge Dr. Carol Anderson, whose enthusiasm for the work encouraged and inspired me. Her humor and insight made the journey much more fun and meaningful. Thanks also should be extended to Dr. Charles N. Davis, who helped guide me through my graduate program and make this work what it is. To Professor Richard C. Reuben, special thanks for adding tremendous wisdom to the project. Also, much appreciation to Dr. -

Lobster 73 Summer 2017

www.lobster-magazine.co.uk Sumer 2017 Lobster • The view from the bridge, by Robin Ramsay • Brexit: an accident waiting to happen, by Simon Matthews • Team mercenary GB Part 2 – This is the 73 modern world, by Nick Must • Blackmail in the Deep State, by Jonathan Marshall • Colin Wallace and the Historical Institutional Abuse Inquiry, by Robin Ramsay • Blair and Israel, by Robin Ramsay • Sex scandals and sexual blackmail in America’s deep politics, by Jonathan Marshall • The Hess flight: still dangerous for historians – even after 75 years, by Andrew Rosthorn • Deaths in Parliament: a legend re- examined, by Garrick Alder • The Russian Laundromat and Blackpool Football Club, by Andrew Rosthorn • A Jimmy Savile sex scandal concealed during the 1997 General Election, by Garrick Alder Book Reviews • Faustian Bargains: Lyndon Johnson and Mac Wallace in the robber baron culture of Texas, by Joan Mellen, reviewed by Robin Ramsay • The CIA As Organised Crime: How Illegal Operations Corrupt America and the World, by Douglas Valentine, reviewed by Dr. T. P. Wilkinson • The Field of Fight: How We Can Win the Global War Against Radical Islam and Its Allies, by Lt. General Michael T Flynn and Michael Ledeen, reviewed by John Newsinger • Of G-Men and Eggheads: The FBI and the New York intellectuals, by John Rodden, reviewed by John Newsinger www.lobster-magazine.co.uk The view from the bridge Robin Ramsay My thanks to Nick Must and Garrick Alder for editorial and proof- reading assistance in this edition of Lobster. The long URL in the footnotes problem There is a problem with long URLs in the footnotes. -

The Progressive Era: the Muckrakers – Answer Key

Name_______________________________________________________ Date__________________ Period______ THE PROGRESSIVE ERA: THE MUCKRAKERS – ANSWER KEY HOW DO WE SOLVE PROBLEMS IN SOCIETY? Many literary minds of the late 1800s began to consider problems faced by the poor as well as the corruption of government and large corporations. Naturally, they put their talents to work, most often using fiction based on fact, but sometimes writing straight documentaries. The term “muckrakers” was coined by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1906 in reference to their ability to uncover “muck,” or “dirt.” Method used to expose Reform(s) made as a Muckraker Problem in Society the problem result Secret ballots: Corruption of city governments Thomas Nast created States began allowing people to cast votes in private; bosses In many large cities, political bosses - political cartoons that 1. Thomas Nast could no longer intimidate like Boss Tweed in New York City - exposed corrupt political voters into choosing the controlled work done for city services bosses like Boss William candidate the boss wanted. like garbage collection and sewers. Tweed. Even though These bosses would help poor Primaries: immigrants couldn't read, immigrants with their basic needs. In Each party began holding they could understand his primary elections – smaller exchange, the bosses would tell the elections held before the main immigrants to vote for the politician cartoons! They learned how they were being taken election in which voters (not Many voted more than once. Also, city the bosses) would choose the politicians often got their jobs based advantage of. Nast’s candidates for each party. on who they knew in power rather cartoons actually helped to Those candidates then run than their qualifications.