What Is a Muckraker? (PDF, 67

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steering Committee

Steering Committee Steven Aftergood Federation of American Scientists Coalition Activities 21 July 2010 – 20 October 2010 Bill Allison Sunlight Foundation OTG engages in a variety of campaigns initiated by coalition staff, and by other partners Mary Alice Baish American Association themselves. Most of what the staff does is in coordination with partners and with others of Law Libraries outside the coalition. We are regularly asked to coordinate other groups and to identify Gary Bass* OMB Watch possible partners for campaigns. Tom Blanton* Advance the right-to-know at the federal and state levels through legislative National Security Archive and other vehicles/ Strengthen coordination and engagement of organizations Danielle Brian currently working on right to know and anti-secrecy issues Project on Government Oversight Promote and Sustain Openness and Transparency/ Promote a Culture of Openness in Government Lucy Dalglish Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Open Government Directive/Open Government Plans Press The coalition has continued monitoring and measuring federal agencies' progress Charles Davis National Freedom of toward fulfilling President Obama’s commitment to “creating an unprecedented level of Information Coalition openness in Government." Results of re-evaluations of open government plans that Leslie Harris were updated between their initial release and June 25, and updated audit results were Center for Democracy & Technology posted to the coalition’s Open Government Plans Audit site Robert Leger (http://sites.google.com/site/opengovtplans/) in July. Society of Professional Journalists Conrad Martin The updated results also include evaluations of plans produced by entities that were not Fund for Constitutional Government required to produce plans, but did so anyway. -

The Future of Investigative Journalism: Global, Networked and Collaborative

The Future of Investigative Journalism: Global, Networked and Collaborative Ellen Hume and Susan Abbott March 2017 Note: This report is extracted from our recent evaluation of the Global Investigative Journalism Network (GIJN) for the Adessium Foundation. Ellen Hume would like to thank especially David Kaplan, Susan Abbott, Anya Schiffrin, Ethan Zuckerman, James Hamilton, Tom Rosenstiel, Bruce Shapiro, Marina Guevara Walker and Brant Houston for their insights. 2 1. Overview: The Investigative Media Landscape The internet and DIY communication tools have weakened the commercial mainstream media, and authoritarian political actors in many once-promising democratic regions are compromising public media independence. Fewer journalists were murdered in 2016 than the previous year, but the number of attacks on journalists around the world is “unprecedented,” according to the Index on Censorship.1 Even the United States, once considered the gold standard for press freedom, has a president who maligns the mainstream news media as “enemies of the people.” An unexpectedly bright spot in this media landscape is the growth of local and cross-border investigative journalism, including the emergence of scores of local nonprofit investigative journalism organizations, often populated by veterans seeking honest work after their old organizations have imploded or been captured by political partisans. These journalism “special forces,” who struggle to maintain their independence, are working in dangerous environments, with few stable resources to support them. Despite the dangers and uncertainties, it is an exciting time to be an investigative journalist, thanks to new collaborations and digital tools. These nonprofits are inventing a potent form of massive, cross-border investigative reporting, supported by philanthropy. -

Realism, Photography and Journalistic Objectivity in 19Th Century America

Studies in Visual Communication Volume 4 Issue 2 Winter 1977 Article 5 1977 Realism, Photography and Journalistic Objectivity in 19th Century America Dan Schiller Recommended Citation Schiller, D. (1977). Realism, Photography and Journalistic Objectivity in 19th Century America. 4 (2), 86-98. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/svc/vol4/iss2/5 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/svc/vol4/iss2/5 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Realism, Photography and Journalistic Objectivity in 19th Century America This contents is available in Studies in Visual Communication: https://repository.upenn.edu/svc/vol4/iss2/5 the whole field of 19th century painterly and literary art. The key assumption of photographic realism-that precisely accurate and complete copies of reality could be produced from symbolic materials-was rather freely translated across numerous visual and verbal codes, and not only within the REALISM, PHOTOGRAPHY accepted realm of art. After first explicating the general sig AND JOURNALISTIC OBJECTIVITY nificance of this increasingly ubiquitous assumption, I will IN 19th CENTURY AMERICA tentatively explore some of its consequences for literature and for journalism. DAN SCHILLER A JOUST WITH "REALISM" When we commend a work of art as being "realistic," we Hostile critics often choose to equate realism per se with commonly mean that it succeeds at faithfully copying events the demonstration of a few apparently basic qualities in or conditions in the "real" world. How can we believe that works of art. Foremost among these is "objectivity." Wellek pictures and writings can be made so as to copy, truly and (1963 :253), for example, defines realism as "the objective accurately, a "natural" reality? The search for an answer to representation of contemporary social reality." Hemmings this deceptively simple question motivates the present essay. -

![Defamation Bill [HL], 127 of 1995-96: Law and Procedure](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1549/defamation-bill-hl-127-of-1995-96-law-and-procedure-161549.webp)

Defamation Bill [HL], 127 of 1995-96: Law and Procedure

Defamation Bill [HL], Bill 127 of 1995-96: Law and Procedure Research Paper 96/60 16 May 1996 This paper seeks to give a brief outline of the law of defamation and to explain the main provisions of the Defamation Bill [HL] which is due to have its Second Reading on 21 May 1996. Although the paper deals mainly with the changes proposed to law and procedure in England and Wales it is pointed out where the changes affect Scotland and Northern Ireland. This paper should be read in conjuction with Research Paper 96/61 which discusses parliamentary privilege in the context of the law of defamation and the interpretation of 'proceedings in Parliament'. Helena Jeffs Home Affairs Section House of Commons Library Summary The Defamation Bill [HL] is intended to "simplify this complex area of law and procedure, and fit well with current developments in the conduct of civil litigation generally".1 In brief the Bill seeks to introduce the following amendments to the law and procedure in actions for defamation: a new statutory defence to supersede the common law defence of innocent dissemination and to concentrate on the concept of responsibility for publication a new and more streamlined defence of unintentional defamation which would be available to a defendant who is willing to make an 'offer of amends' (ie to pay compensation assessed by a judge and to publish an appropriate correction and apology) a one-year limitation period for actions for libel, slander or malicious falsehood a new fast-track offer of amends procedure intended to provide a prompt and inexpensive remedy in less serious defamation cases new powers for judges enabling them to dispose of a claim summarily and to grant damages of up to £10,000 There has long been consensus on the need for reform of defamation law and procedure, particularly in view of certain high awards of damages by juries and the high costs of proceedings. -

How to Fund Investigative Journalism Insights from the Field and Its Key Donors Imprint

EDITION DW AKADEMIE | 2019 How to fund investigative journalism Insights from the field and its key donors Imprint PUBLISHER RESPONSIBLE PUBLISHED Deutsche Welle Jan Lublinski September 2019 53110 Bonn Carsten von Nahmen Germany © DW Akademie EDITORS AUTHOR Petra Aldenrath Sameer Padania Nadine Jurrat How to fund investigative journalism Insights from the field and its key donors Sameer Padania ABOUT THE REPORT About the report This report is designed to give funders a succinct and accessible introduction to the practice of funding investigative journalism around the world, via major contemporary debates, trends and challenges in the field. It is part of a series from DW Akademie looking at practices, challenges and futures of investigative journalism (IJ) around the world. The paper is intended as a stepping stone, or a springboard, for those who know little about investigative journalism, but who would like to know more. It is not a defense, a mapping or a history of the field, either globally or regionally; nor is it a description of or guide to how to conduct investigations or an examination of investigative techniques. These are widely available in other areas and (to some extent) in other languages already. Rooted in 17 in-depth expert interviews and wide-ranging desk research, this report sets out big-picture challenges and oppor- tunities facing the IJ field both in general, and in specific regions of the world. It provides donors with an overview of the main ways this often precarious field is financed in newsrooms and units large and small. Finally it provides high-level practical ad- vice — from experienced donors and the IJ field — to help new, prospective or curious donors to the field to find out how to get started, and what is important to do, and not to do. -

The Discursive Construction of the Gamification of Journalism

Archived version from NCDOCKS Institutional Repository http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/asu/ The Discursive Construction Of The Gamification Of Journalism By: Tim P. Vos and Gregory P. Perreault Abstract This study explores the discursive, normative construction of gamification within journalism. Rooted in a theory of discursive institutionalism and by analyzing a significant corpus of metajournalistic discourse from 2006 to 2019, the study demonstrates how journalists have negotiated gamification’s place within journalism’s boundaries. The discourse addresses criticism that gamified news is a move toward infotainment and makes the case for gamification as serious journalism anchored in norms of audience engagement. Thus, gamification does not constitute institutional change since it is construed as an extension of existing institutional norms and beliefs. Vos TP, Perreault GP. The discursive construction of the gamification of journalism. Convergence. 2020;26(3):470-485. doi:10.1177/1354856520909542. Publisher version of record available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1354856520909542 Special Issue: Article Convergence: The International Journal of Research into The discursive construction New Media Technologies 2020, Vol. 26(3) 470–485 ª The Author(s) 2020 of the gamification of journalism Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI: 10.1177/1354856520909542 journals.sagepub.com/home/con Tim P Vos Michigan State University, USA Gregory P Perreault Appalachian State University, USA Abstract This study explores the discursive, normative construction of gamification within journalism. Rooted in a theory of discursive institutionalism and by analyzing a significant corpus of meta- journalistic discourse from 2006 to 2019, the study demonstrates how journalists have negotiated gamification’s place within journalism’s boundaries. -

Beyond Objectivity and Relativism: a View Of

BEYOND OBJECTIVITY AND RELATIVISM: A VIEW OF JOURNALISM FROM A RHETORICAL PERSPECTIVE A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Catherine Meienberg Gynn, B.A., M.A. The Ohio State University 1995 Dissertation Committee Approved by Josina M. Makau Susan L. Kline Adviser Paul V. Peterson Department of Communication Joseph M. Foley UMI Number: 9533982 UMI Microform 9533982 Copyright 1995, by UMI Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. UMI 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, MI 48103 DEDICATION To my husband, Jack D. Gynn, and my son, Matthew M. Gynn. With thanks to my parents, Alyce W. Meienberg and the late John T. Meienberg. This dissertation is in respectful memory of Lauren Rudolph Michael James Nole Celina Shribbs Riley Detwiler young victims of the events described herein. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I express sincere appreciation to Professor Josina M. Makau, Academic Planner, California State University at Monterey Bay, whose faith in this project was unwavering and who continually inspired me throughout my graduate studies, and to Professor Susan Kline, Department of Communication, The Ohio State University, whose guidance, friendship and encouragement made the final steps of this particular journey enjoyable. I wish to thank Professor Emeritus Paul V. Peterson, School of Journalism, The Ohio State University, for guidance that I have relied on since my undergraduate and master's programs, and whose distinguished participation in this project is meaningful to me beyond its significant academic merit. -

Annotated Bibliography

Annotated Bibliography Primary Sources Ang, Tom. Photography: the Definitive Visual History. DK Publishing, 2014. This primary source provides me with information on Lewis Hine. Lewis Hine had skills of a great photographer. His photography made an impact on child labor laws. Hine was a muckraker, for he went undercover having people take photographic surveys of child labor from 1908 to 1918. “A Photograph of a Settlement House Kindergarten in Chicago, Illinois, 1901.” A Photograph of a Settlement House Kindergarten in Chicago, Illinois, 1901. | DPLA, dp.la/primary-source-sets/settlement-houses-in-the-progressive-era/sources/1168. This picture was used for a title background. It is a picture of a settlement house. Augustine, Jackie. “The Original Kodak Moment: Snapshots Taken from the Camera That Changed Photography in 1888.” The Imaging Alliance, The Imaging Alliance, 1 Oct. 2013, www.theimagingalliance.com/the-original-kodak-moment-snapshots-taken-from-the-camer a-that-changed-photography-in-1888/. I used the photo of a Kodak camera from this site for a title background. Bellis, Mary. “The History of Kodak: How Rolled Film Made Everyone a Photographer.” ThoughtCo, ThoughtCo, 5 Oct. 2019, www.thoughtco.com/george-eastman-history-of-kodak-1991619. The Kodak camera had different settings. This website includes information from the original Kodak Manual. There were certain ways to use the camera, as for a camera nowadays. Just like a professional camera now, the kodak had settings for exposure. Durkin, Erin. “Women's March 2019: Thousands to Protest across US.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 19 Jan. 2019, www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/jan/19/womens-march-2019-protests-latest-event. -

Media & Ethics

global issues An Electronic Journal of the U.S. Department of State • April 2001 Volume 6, Number 1 “America’s hometown papers, whether large or small, chronicle the daily life of our nation, of our people .... Put it all together, and community newspapers do not just tell the story of American freedom, (they) are that story.” Colin Powell, U.S. Secretary of State Speech to the American Newspaper Association, March 25, 2001 2 From the Editors The United States’ constitutional guarantees of free press and free expression have ensured a press largely without governmental regulation. This does not mean media without standards. In this journal, noted U.S. experts explore the central role of media ethics as the core values that shape the functioning of U.S. journalism. In the American system, our free media is an essential source of the information that is at the heart of a free society. This critical role endows the media with its own power, which, when used irresponsibly, can threaten a free society. How, then, do we manage this challenge? In many nations, the government takes on the role of primary regulator of the media. In the United States, our solution has been to rely on market forces, competition, responsi- bility, and a highly evolved set of self-controls that we call journalism ethics. Journalism ethics provide a process by which individual mistakes and excesses are cor- rected without jeopardizing the ultimate objective of a free media—to provide a healthy check on centers of power in order to maintain a free and enlightened society. -

Outline for Introduction

Introduction Twentieth-century American journalism was born in a little-remembered burst of inspired self-promotion. It was born in a paroxysm of yellow journalism. Ten seconds into the century, the first issue of the New York Journal of 1 January 1901 fell from the newspaper’s complex of fourteen high- speed presses. The first issue was rushed by automobile across pave- ments slippery with mud and rain to a waiting express train, reserved especially for the occasion. The newspaper was folded into an engraved silver case and carried aboard by Langdon Smith, a young reporter known for his vivid prose style. At speeds that reached eighty miles an hour, the special train raced through the darkness to Washington, D.C., and Smith’s rendezvous with the president, William McKinley. The president’s personal secretary made no mention in his diary of the special delivery of the Journal that day, noting instead that the New Year’s reception at the executive mansion had attracted 5,500 well- wishers and was said to have been “the most successful for many years.”1 But the Journal exulted: A banner headline spilled across the front page of the 2 January 1901 issue, asserting the Journal’s distinction of having published “the first Twentieth Century newspaper . in this country,” and that the first issue had been delivered at considerable ex- pense and effort directly to McKinley.2 There was a lot of yellow journalism in Smith’s turn-of-the-century run to Washington. The occasion illuminated the qualities that made the genre—of which the New York Journal was an archetype—both so irritat- ing and so irresistible: Yellow journalism could be imaginative yet frivo- lous, aggressive yet self-indulgent. -

“Yellow-Kid Reporter” Era, and Artifice

Introduction American Children’s Literature, the “Yellow-Kid Reporter” Era, and Artifice Pretend it’s 1896. You live in New York City. It’s Sunday. That means today is the day for the supplement edition of The World news- paper, and that means Hogan’s Alley and the Yellow Kid. In the days when the printed newspaper defined the world for the reading public, Joseph Pulitzer’s World attempted to report and reimagine it in bold, innovative ways, including through the use of color and comics. Hogan’s Alley, a one-panel illustration starring the uncouth Yellow Kid and his gang of street children, became one of the pioneers of this daring, fledgling form that had discovered a new way to—well, what exactly did it do? The introduction of bright visual hues and irreverent characters made it a novelty feature and popular amusement. But it also functioned as biting political satire and cultural commentary, and it did so through the figures of children. Whether young or old, it’s not unlikely that you would have eagerly sought out a copy of The World on Sundays. But what “news” of the world would you have absorbed? What was the Yellow Kid reporting to his readers? If you had picked up the Sunday World on July 26, 1896, you may have skipped straight to the supplement to see the new raucous Hogan’s Alley. It might not have been giving its audience new information about the latest hap- penings in New York or Washington, but in some fashion, it was usually saying something about those happenings. -

Muckraker Project.Pdf

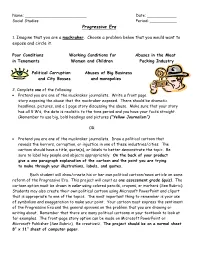

Name: _________________________ Date: ____________ Social Studies Period: ___________ Progressive Era 1. Imagine that you are a muckraker. Choose a problem below that you would want to expose and circle it. Poor Conditions Working Conditions for Abuses in the Meat in Tenements Women and Children Packing Industry Political Corruption Abuses of Big Business and City Bosses and monopolies 2. Complete one of the following: • Pretend you are one of the muckraker journalists. Write a front page story exposing the abuse that the muckraker exposed. There should be dramatic headlines, pictures, and a 1 page story discussing the abuse. Make sure that your story has all 5 W’s, the date is realistic to the time period and you have your facts straight. (Remember to use big, bold headings and pictures (“Yellow Journalism”) OR • Pretend you are one of the muckraker journalists. Draw a political cartoon that reveals the horrors, corruption, or injustice in one of these industries/cities. The cartoon should have a title, quote(s), or labels to better demonstrate the topic. Be sure to label key people and objects appropriately. On the back of your product give a one paragraph explanation of the cartoon and the point you are trying to make through your illustrations, labels, and quotes. Each student will draw/create his or her own political cartoon/news article on some reform of the Progressive Era. This project will count as one assessment grade (quiz). The cartoon option must be drawn in color using colored pencils, crayons, or markers (See Rubric). Students may also create their own political cartoon using Microsoft PowerPoint and clipart that is appropriate to one of the topics.