Realism, Photography and Journalistic Objectivity in 19Th Century America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steering Committee

Steering Committee Steven Aftergood Federation of American Scientists Coalition Activities 21 July 2010 – 20 October 2010 Bill Allison Sunlight Foundation OTG engages in a variety of campaigns initiated by coalition staff, and by other partners Mary Alice Baish American Association themselves. Most of what the staff does is in coordination with partners and with others of Law Libraries outside the coalition. We are regularly asked to coordinate other groups and to identify Gary Bass* OMB Watch possible partners for campaigns. Tom Blanton* Advance the right-to-know at the federal and state levels through legislative National Security Archive and other vehicles/ Strengthen coordination and engagement of organizations Danielle Brian currently working on right to know and anti-secrecy issues Project on Government Oversight Promote and Sustain Openness and Transparency/ Promote a Culture of Openness in Government Lucy Dalglish Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Open Government Directive/Open Government Plans Press The coalition has continued monitoring and measuring federal agencies' progress Charles Davis National Freedom of toward fulfilling President Obama’s commitment to “creating an unprecedented level of Information Coalition openness in Government." Results of re-evaluations of open government plans that Leslie Harris were updated between their initial release and June 25, and updated audit results were Center for Democracy & Technology posted to the coalition’s Open Government Plans Audit site Robert Leger (http://sites.google.com/site/opengovtplans/) in July. Society of Professional Journalists Conrad Martin The updated results also include evaluations of plans produced by entities that were not Fund for Constitutional Government required to produce plans, but did so anyway. -

Objectivity – an Ideal Or a Misunderstanding?

Chapter 3 Objectivity – An Ideal or a Misunderstanding? Elsebeth Frey Objectivity is often seen as an emblem of Western journalism, but in the developed countries the notion of objectivity has declined. Still, journalists from other parts of the world point to it as an export of Western, especially American, journalism. At the same time, American journalism teachers impress on their students the futility of objectivity, and Alex Jones writes that ‘we may be living through what could be considered objectivity’s last stand’ (Jones 2009). As Durham states (1998:118) ‘journalistic objectivity has always been a slippery notion’. Research shows that objectivity worldwide ‘is present and locally generated and negotiated in several ways’ (Krøvel et al. 2012:24). The concept of objectivity has many layers, and one could say that the perception of it is tainted with misunderstandings. As Muñoz-Torres (2012) emphasizes, its philosophical origin is rooted in how we see the world, our understanding of what knowledge is and our perception of the truth. Others write about a practical (Jones 2009) or functional (Rhaman 2017) truth as the one journalists are aiming to discern. This study explores objectivity as seen by journalists and journalism students transnationally, although very much rooted in their culture and politics, specifically in Norway, Tunisia and Bangladesh. Are there differences and/or similarities, and if so, what are they? Furthermore, armed with theoretical approaches from Streckfuss (1990) and Muñoz-Torres (2012), among others, the aim of this chapter is to clarify different positions, as well as views among our interviewees. The notion of objectivity in journalism Richard Streckfuss (1990) looked at historical documents in order to trace when and why objectivity was introduced to journalism in the USA. -

Ethics in Photojournalism: Past, Present, and Future

Ethics in Photojournalism: Past, Present, and Future By Daniel R. Bersak S.B. Comparative Media Studies & Electrical Engineering/Computer Science Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2003 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SEPTEMBER, 2006 Copyright 2006 Daniel R. Bersak, All Rights Reserved The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: _____________________________________________________ Department of Comparative Media Studies, August 11, 2006 Certified By: ___________________________________________________________ Edward Barrett Senior Lecturer, Department of Writing Thesis Supervisor Accepted By: __________________________________________________________ William Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies Director Ethics In Photojournalism: Past, Present, and Future By Daniel R. Bersak Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies, School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences on August 11, 2006, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies Abstract Like writers and editors, photojournalists are held to a standard of ethics. Each publication has a set of rules, sometimes written, sometimes unwritten, that governs what that publication considers to be a truthful and faithful representation of images to the public. These rules cover a wide range of topics such as how a photographer should act while taking pictures, what he or she can and can’t photograph, and whether and how an image can be altered in the darkroom or on the computer. -

![Defamation Bill [HL], 127 of 1995-96: Law and Procedure](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1549/defamation-bill-hl-127-of-1995-96-law-and-procedure-161549.webp)

Defamation Bill [HL], 127 of 1995-96: Law and Procedure

Defamation Bill [HL], Bill 127 of 1995-96: Law and Procedure Research Paper 96/60 16 May 1996 This paper seeks to give a brief outline of the law of defamation and to explain the main provisions of the Defamation Bill [HL] which is due to have its Second Reading on 21 May 1996. Although the paper deals mainly with the changes proposed to law and procedure in England and Wales it is pointed out where the changes affect Scotland and Northern Ireland. This paper should be read in conjuction with Research Paper 96/61 which discusses parliamentary privilege in the context of the law of defamation and the interpretation of 'proceedings in Parliament'. Helena Jeffs Home Affairs Section House of Commons Library Summary The Defamation Bill [HL] is intended to "simplify this complex area of law and procedure, and fit well with current developments in the conduct of civil litigation generally".1 In brief the Bill seeks to introduce the following amendments to the law and procedure in actions for defamation: a new statutory defence to supersede the common law defence of innocent dissemination and to concentrate on the concept of responsibility for publication a new and more streamlined defence of unintentional defamation which would be available to a defendant who is willing to make an 'offer of amends' (ie to pay compensation assessed by a judge and to publish an appropriate correction and apology) a one-year limitation period for actions for libel, slander or malicious falsehood a new fast-track offer of amends procedure intended to provide a prompt and inexpensive remedy in less serious defamation cases new powers for judges enabling them to dispose of a claim summarily and to grant damages of up to £10,000 There has long been consensus on the need for reform of defamation law and procedure, particularly in view of certain high awards of damages by juries and the high costs of proceedings. -

Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media Jason Mccoy University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Professional Projects from the College of Journalism Journalism and Mass Communications, College of and Mass Communications Spring 4-18-2019 Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media Jason McCoy University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/journalismprojects Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Mass Communication Commons, and the Other Communication Commons McCoy, Jason, "Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media" (2019). Professional Projects from the College of Journalism and Mass Communications. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/journalismprojects/20 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Journalism and Mass Communications, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Professional Projects from the College of Journalism and Mass Communications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media Jason Mccoy University of Nebraska-Lincoln This paper will examine the development of modern media ethics and will show that this set of guidelines can and perhaps should be revised and improved to match the challenges of an economic and political system that has taken advantage of guidelines such as “objective reporting” by creating too many false equivalencies. This paper will end by providing a few reforms that can create a better media environment and keep the public better informed. As it was important for journalism to improve from partisan media to objective reporting in the past, it is important today that journalism improves its practices to address the right-wing media’s attack on journalism and avoid too many false equivalencies. -

Valuing Subjectivity in Journalism: Bias, Emotions, and Self-Interest As Tools in Arts Reporting

Original Article Journalism Valuing subjectivity in journalism: Bias, emotions, and self-interest as tools in arts reporting Phillipa Chong McMaster University, Canada Abstract This article examines the meanings and norms surrounding subjectivity across traditional and new forms of cultural journalism. While the ideal of objectivity is key to American journalism and its development as a profession, recent scholarship and new media developments have challenged the dominance of objectivity as a professional norm. This article begins with the understanding that subjectivity is an intractable part of knowing (and reporting on) the world around us to build our understanding of different modes of subjectivity and how these animate journalistic practices. Taking arts reporting, specifically reviewing, as a case study, the analysis draws on interviews with 40 book reviewers who write for major American newspapers, including The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, and prominent blogs. Findings reveal how emotions, bias, and self-interest are salient – sometimes as vice and sometimes as virtue – across the workflow of critics writing for traditional print outlets and book blogs and that these differences can be conceptualized as different epistemic styles. Keywords Blogs, emotion, literary journalism, newspapers, online media, practice, subjectivity/ objectivity Introduction Objectivity has long been the gold standard in American journalism and was key to its development into a profession (Benson and Neveu, 2005; Schudson, 1976). Yet Corresponding author: Phillipa Chong, Department of Sociology, McMaster University, 609 Kenneth Taylor Hall, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, ON L8S 4M4, Canada. Email: [email protected] Chong 2 scholars have complicated the picture by pointing to the unattainability of objectivity as an ideal with some noting the increasing acceptance of subjectivity across different forms of journalism (Tumber and Prentoulis, 2003; Wahl-Jorgensen, 2012, 2013; Zelizer, 2009b). -

Beyond Objectivity and Relativism: a View Of

BEYOND OBJECTIVITY AND RELATIVISM: A VIEW OF JOURNALISM FROM A RHETORICAL PERSPECTIVE A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Catherine Meienberg Gynn, B.A., M.A. The Ohio State University 1995 Dissertation Committee Approved by Josina M. Makau Susan L. Kline Adviser Paul V. Peterson Department of Communication Joseph M. Foley UMI Number: 9533982 UMI Microform 9533982 Copyright 1995, by UMI Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. UMI 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, MI 48103 DEDICATION To my husband, Jack D. Gynn, and my son, Matthew M. Gynn. With thanks to my parents, Alyce W. Meienberg and the late John T. Meienberg. This dissertation is in respectful memory of Lauren Rudolph Michael James Nole Celina Shribbs Riley Detwiler young victims of the events described herein. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I express sincere appreciation to Professor Josina M. Makau, Academic Planner, California State University at Monterey Bay, whose faith in this project was unwavering and who continually inspired me throughout my graduate studies, and to Professor Susan Kline, Department of Communication, The Ohio State University, whose guidance, friendship and encouragement made the final steps of this particular journey enjoyable. I wish to thank Professor Emeritus Paul V. Peterson, School of Journalism, The Ohio State University, for guidance that I have relied on since my undergraduate and master's programs, and whose distinguished participation in this project is meaningful to me beyond its significant academic merit. -

Annotated Bibliography

Annotated Bibliography Primary Sources Ang, Tom. Photography: the Definitive Visual History. DK Publishing, 2014. This primary source provides me with information on Lewis Hine. Lewis Hine had skills of a great photographer. His photography made an impact on child labor laws. Hine was a muckraker, for he went undercover having people take photographic surveys of child labor from 1908 to 1918. “A Photograph of a Settlement House Kindergarten in Chicago, Illinois, 1901.” A Photograph of a Settlement House Kindergarten in Chicago, Illinois, 1901. | DPLA, dp.la/primary-source-sets/settlement-houses-in-the-progressive-era/sources/1168. This picture was used for a title background. It is a picture of a settlement house. Augustine, Jackie. “The Original Kodak Moment: Snapshots Taken from the Camera That Changed Photography in 1888.” The Imaging Alliance, The Imaging Alliance, 1 Oct. 2013, www.theimagingalliance.com/the-original-kodak-moment-snapshots-taken-from-the-camer a-that-changed-photography-in-1888/. I used the photo of a Kodak camera from this site for a title background. Bellis, Mary. “The History of Kodak: How Rolled Film Made Everyone a Photographer.” ThoughtCo, ThoughtCo, 5 Oct. 2019, www.thoughtco.com/george-eastman-history-of-kodak-1991619. The Kodak camera had different settings. This website includes information from the original Kodak Manual. There were certain ways to use the camera, as for a camera nowadays. Just like a professional camera now, the kodak had settings for exposure. Durkin, Erin. “Women's March 2019: Thousands to Protest across US.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 19 Jan. 2019, www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/jan/19/womens-march-2019-protests-latest-event. -

N Ieman Reports

NIEMAN REPORTS Nieman Reports One Francis Avenue Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 Nieman Reports THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY VOL. 62 NO. 1 SPRING 2008 VOL. 62 NO. 1 SPRING 2008 21 ST CENTURY MUCKRAKERS THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION HARVARDAT UNIVERSITY 21st Century Muckrakers Who Are They? How Do They Do Their Work? Words & Reflections: Secrets, Sources and Silencing Watchdogs Journalism 2.0 End Note went to the Carnegie Endowment in New York but of the Oakland Tribune, and Maynard was throw- found times to return to Cambridge—like many, ing out questions fast and furiously about my civil I had “withdrawal symptoms” after my Harvard rights coverage. I realized my interview was lasting ‘to promote and elevate the year—and would meet with Tenney. She came to longer than most, and I wondered, “Is he trying to my wedding in Toronto in 1984, and we tried to knock me out of competition?” Then I happened to keep in touch regularly. Several of our class, Peggy glance over at Tenney and got the only smile from standards of journalism’ Simpson, Peggy Engel, Kat Harting, and Nancy the group—and a warm, welcoming one it was. I Day visited Tenney in her assisted living facility felt calmer. Finally, when the interview ended, I in Cambridge some years ago, during a Nieman am happy to say, Maynard leaped out of his chair reunion. She cared little about her own problems and hugged me. Agnes Wahl Nieman and was always interested in others. Curator Jim Tenney was a unique woman, and I thoroughly Thomson was the public and intellectual face of enjoyed her friendship. -

The Digital Animation of Literary Journalism

JOU0010.1177/1464884914568079JournalismJacobson et al. 568079research-article2015 Article Journalism 1 –20 The digital animation of © The Author(s) 2015 Reprints and permissions: literary journalism sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1464884914568079 jou.sagepub.com Susan Jacobson Florida International University, USA Jacqueline Marino Kent State University, USA Robert E Gutsche Jr Florida International University, USA Abstract Since The New York Times published Snow Fall in 2012, media organizations have produced a growing body of similar work characterized by the purposeful integration of multimedia into long-form journalism. In this article, we argue that just as the literary journalists of the 1960s attempted to write the nonfiction equivalent of the great American novel, journalists of the 2010s are using digital tools to animate literary journalism techniques. To evaluate whether this emerging genre represents a new era of literary journalism and to what extent it incorporates new techniques of journalistic storytelling, we analyze 50 long-form multimedia journalism packages published online from August 2012 to December 2013. We argue that this new wave of literary journalism is characterized by executing literary techniques through multiple media and represents a gateway to linear storytelling in the hypertextual environment of the Web. Keywords Content analysis, literary journalism, long-form, multimedia, New Journalism, storytelling Introduction As news has evolved, journalists have experimented with new formats to enhance and transform the news-consumption experience (Barnhurst, 2010; Pauly, 2014). The use of Corresponding author: Susan Jacobson, School of Journalism and Mass Communication, Florida International University, 3000 NE 151 Street, AC2, North Miami, FL 33181, USA. Email: [email protected] 2 Journalism literary techniques in journalism has been one of the methods that reporters and editors have employed to create variety in news storytelling. -

Muckraker Project.Pdf

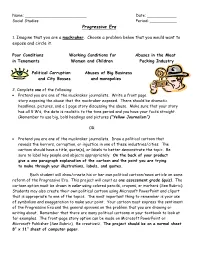

Name: _________________________ Date: ____________ Social Studies Period: ___________ Progressive Era 1. Imagine that you are a muckraker. Choose a problem below that you would want to expose and circle it. Poor Conditions Working Conditions for Abuses in the Meat in Tenements Women and Children Packing Industry Political Corruption Abuses of Big Business and City Bosses and monopolies 2. Complete one of the following: • Pretend you are one of the muckraker journalists. Write a front page story exposing the abuse that the muckraker exposed. There should be dramatic headlines, pictures, and a 1 page story discussing the abuse. Make sure that your story has all 5 W’s, the date is realistic to the time period and you have your facts straight. (Remember to use big, bold headings and pictures (“Yellow Journalism”) OR • Pretend you are one of the muckraker journalists. Draw a political cartoon that reveals the horrors, corruption, or injustice in one of these industries/cities. The cartoon should have a title, quote(s), or labels to better demonstrate the topic. Be sure to label key people and objects appropriately. On the back of your product give a one paragraph explanation of the cartoon and the point you are trying to make through your illustrations, labels, and quotes. Each student will draw/create his or her own political cartoon/news article on some reform of the Progressive Era. This project will count as one assessment grade (quiz). The cartoon option must be drawn in color using colored pencils, crayons, or markers (See Rubric). Students may also create their own political cartoon using Microsoft PowerPoint and clipart that is appropriate to one of the topics. -

Journalism and Democracy: Towards a Contemporary Research Strategy in Mexico

Journalism and Democracy: Towards a Contemporary Research Strategy in Mexico. Professor Natalie Fenton Goldsmiths, University of London Department of Media and Communications New Cross London SE14 6NW UK T: +44(0)20 7919 7620 Email: [email protected] 1 Section 1: News Journalism and Democracy: why it matters and the issues involved A healthy news media is often claimed to be the life-blood of democracy. This is because news provides, or should provide, the vital resources for processes of information gathering, deliberation and analysis that enables citizens to participate in political life and democracy to function better. For this to happen we need the news to represent a wide range of issues from a variety of perspectives and with a diversity of voices. It requires a journalism that operates freely and without interference from state institutions, corporate pressures or fear of intimidation and persecution. In an ideal world this would mean that news media would survey the socio-political environment, hold the powerful to account, provide a platform for intelligible and illuminating debate, and encourage dialogue across a range of views. However, this is an ideal relationship hinged on a conception of independent journalism in the public interest – journalism as fourth estate linked to notions of public knowledge, political participation and democratic renewal. The reality is often quite different. Identifying the gap between the admirable aspiration of a fully functioning public sphere and the conditions of practice and production of news media and then understanding why this gap exists is critical to understanding how our democracies can function better.