Outline for Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Discursive Construction of the Gamification of Journalism

Archived version from NCDOCKS Institutional Repository http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/asu/ The Discursive Construction Of The Gamification Of Journalism By: Tim P. Vos and Gregory P. Perreault Abstract This study explores the discursive, normative construction of gamification within journalism. Rooted in a theory of discursive institutionalism and by analyzing a significant corpus of metajournalistic discourse from 2006 to 2019, the study demonstrates how journalists have negotiated gamification’s place within journalism’s boundaries. The discourse addresses criticism that gamified news is a move toward infotainment and makes the case for gamification as serious journalism anchored in norms of audience engagement. Thus, gamification does not constitute institutional change since it is construed as an extension of existing institutional norms and beliefs. Vos TP, Perreault GP. The discursive construction of the gamification of journalism. Convergence. 2020;26(3):470-485. doi:10.1177/1354856520909542. Publisher version of record available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1354856520909542 Special Issue: Article Convergence: The International Journal of Research into The discursive construction New Media Technologies 2020, Vol. 26(3) 470–485 ª The Author(s) 2020 of the gamification of journalism Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI: 10.1177/1354856520909542 journals.sagepub.com/home/con Tim P Vos Michigan State University, USA Gregory P Perreault Appalachian State University, USA Abstract This study explores the discursive, normative construction of gamification within journalism. Rooted in a theory of discursive institutionalism and by analyzing a significant corpus of meta- journalistic discourse from 2006 to 2019, the study demonstrates how journalists have negotiated gamification’s place within journalism’s boundaries. -

“Yellow-Kid Reporter” Era, and Artifice

Introduction American Children’s Literature, the “Yellow-Kid Reporter” Era, and Artifice Pretend it’s 1896. You live in New York City. It’s Sunday. That means today is the day for the supplement edition of The World news- paper, and that means Hogan’s Alley and the Yellow Kid. In the days when the printed newspaper defined the world for the reading public, Joseph Pulitzer’s World attempted to report and reimagine it in bold, innovative ways, including through the use of color and comics. Hogan’s Alley, a one-panel illustration starring the uncouth Yellow Kid and his gang of street children, became one of the pioneers of this daring, fledgling form that had discovered a new way to—well, what exactly did it do? The introduction of bright visual hues and irreverent characters made it a novelty feature and popular amusement. But it also functioned as biting political satire and cultural commentary, and it did so through the figures of children. Whether young or old, it’s not unlikely that you would have eagerly sought out a copy of The World on Sundays. But what “news” of the world would you have absorbed? What was the Yellow Kid reporting to his readers? If you had picked up the Sunday World on July 26, 1896, you may have skipped straight to the supplement to see the new raucous Hogan’s Alley. It might not have been giving its audience new information about the latest hap- penings in New York or Washington, but in some fashion, it was usually saying something about those happenings. -

Muckraker Project.Pdf

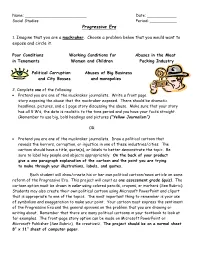

Name: _________________________ Date: ____________ Social Studies Period: ___________ Progressive Era 1. Imagine that you are a muckraker. Choose a problem below that you would want to expose and circle it. Poor Conditions Working Conditions for Abuses in the Meat in Tenements Women and Children Packing Industry Political Corruption Abuses of Big Business and City Bosses and monopolies 2. Complete one of the following: • Pretend you are one of the muckraker journalists. Write a front page story exposing the abuse that the muckraker exposed. There should be dramatic headlines, pictures, and a 1 page story discussing the abuse. Make sure that your story has all 5 W’s, the date is realistic to the time period and you have your facts straight. (Remember to use big, bold headings and pictures (“Yellow Journalism”) OR • Pretend you are one of the muckraker journalists. Draw a political cartoon that reveals the horrors, corruption, or injustice in one of these industries/cities. The cartoon should have a title, quote(s), or labels to better demonstrate the topic. Be sure to label key people and objects appropriately. On the back of your product give a one paragraph explanation of the cartoon and the point you are trying to make through your illustrations, labels, and quotes. Each student will draw/create his or her own political cartoon/news article on some reform of the Progressive Era. This project will count as one assessment grade (quiz). The cartoon option must be drawn in color using colored pencils, crayons, or markers (See Rubric). Students may also create their own political cartoon using Microsoft PowerPoint and clipart that is appropriate to one of the topics. -

What Is a Muckraker? (PDF, 67

What Is a Muckraker? President Theodore Roosevelt popularized the term muckrakers in a 1907 speech. The muckraker was a man in John Bunyan’s 1678 allegory Pilgrim’s Progress who was too busy raking through barnyard filth to look up and accept a crown of salvation. Though Roosevelt probably meant to include “mud-slinging” politicians who attacked others’ moral character rather than debating their ideas, the term has stuck as a reference to journalists who investigate wrongdoing by the rich or powerful. Historical Significance In its narrowest sense, the term refers to long-form, investigative journalism published in magazines between 1900 and World War I. Unlike yellow journalism, the reporters and editors of this period valued accuracy and the aggressive pursuit of information, often by searching through mounds of documents and data and by conducting extensive interviews. It sometimes included first- person reporting. Muckraking was seen in action when Ida M. Tarbell exposed the strong-armed practices of the Standard Oil Company in a 19-part series in McClure’s Magazine between 1902 and 1904. Her exposé helped end the company’s monopoly over the oil industry. Her stories include information from thousands of documents from across the nation as well as interviews with current and former executives, competitors, government regulators, antitrust lawyers and academic experts. It was republished as “The Rise of the Standard Oil Company.” Upton Sinclair’s investigation of the meatpacking industry gave rise to at least two significant federal laws, the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act. Sinclair spent seven weeks as a worker at a Chicago meatpacking plant and another four months investigating the industry, then published a fictional work based on his findings as serial from February to November of 1905 in a socialist magazine. -

Digital Journalism Studies the Key Concepts

Digital Journalism Studies The Key Concepts FRANKLIN, Bob and CANTER, Lily <http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5708-2420> Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/26994/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version FRANKLIN, Bob and CANTER, Lily (2019). Digital Journalism Studies The Key Concepts. Routledge key guides . Routledge. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk <BOOK-PART><BOOK-PART-META><TITLE>The key concepts</TITLE></BOOK- PART-META></BOOK-PART> <BOOK-PART><BOOK-PART-META><TITLE>Actants</TITLE></BOOK-PART- META> <BODY>In a special issue of the journal Digital Journalism, focused on reconceptualizsing key theoretical changes reflecting the development of Digital Journalism Studies, Seth Lewis and Oscar Westlund seek to clarify the role of what they term the “four A’s” – namely the human actors, non-human technological actants, audiences and the involvement of all three groups in the activities of news production (Lewis and Westlund, 2014). Like Primo and Zago, Lewis and Westlund argue that innovations in computational software require scholars of digital journalism to interrogate not simply who but what is involved in news production and to establish how non-human actants are disrupting established journalism practices (Primo and Zago, 2015: 38). The examples of technological actants -

Causes of the Spanish-American War EQ – How Did Yellow Journalism Contribute to the Start of the Spanish-American War?

Name _______________________________________ Date __________________________ Period _______________ Directions: Read the following essay. Highlight or underline key information as you read. Causes of the Spanish-American War EQ – How did yellow journalism contribute to the start of the Spanish-American War? Yellow Journalism The Spanish-American War is often referred to as the first "media war." During the 1890s, journalism that sensationalized—and sometimes even manufactured—dramatic events was a powerful force that helped propel the United States into war with Spain. Led by newspaper owners William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, journalism of the 1890s used exaggerated news stories with sensational headlines to sell millions of newspapers--a style that became known as yellow journalism. The term yellow journalism came from a popular New York World comic called "Hogan's Alley," which featured a yellow-dressed character named the "the yellow kid." Determined to compete with Pulitzer's World in every way, rival New York Journal owner William Randolph Hearst copied Pulitzer's sensationalist style and even hired "Hogan's Alley" artist R.F. Outcault away from the World. In response, Pulitzer commissioned another cartoonist to create a second yellow kid. Soon, the sensationalist press of the 1890s became a competition between the "yellow kids," and the journalistic style was coined "yellow journalism." Yellow journals like the New York Journal and the New York World relied on sensationalist headlines to sell newspapers. William Randolph Hearst understood that a war with Cuba would not only sell his papers, but also move him into a position of national prominence. From Cuba, Hearst's star reporters wrote stories designed to tug at the heartstrings of Americans. -

“Fake News” & Media Literacy

“Fake News” & Media Literacy Susan LoRusso, Ph.D. Assistant Professor University of Minnesota Hubbard School of Journalism & Mass Communication [email protected] Grew up in Luck, WI Lifelong love of the news B.S. from UW-Stout About Me Graduate work at the University of Minnesota Research focus on misinformation, conflicting information, & ambiguous information in the news Teach courses on media literacy for students across campus and our journalism majors • Definition of Media Literacy • The 1st Amendment • Principles & Practices of Journalism Today’s Agenda • Brief Overview of the Evolution of News • Definition of “Fake News” & Examples • Definitions & Examples of Other Types of Problematic Information • Tools to Use to Evaluate Information Media Literacy “The ability to identify different types of media and understand the messages they're sending.“—Common Sense Media “The ability to ACCESS, ANALYZE, EVALUATE, CREATE, and ACT using all forms of communication.” –National Association for Media Literacy Education “Media Literacy is a 21st century approach to education. It provides a framework to access, analyze, evaluate, create and participate with messages in a variety of forms — from print to video to the Internet. Media literacy builds an understanding of the role of media in society as well as essential skills of inquiry and self-expression necessary for citizens of a democracy.” –Center for Media Literacy Trust in Media “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or First Amendment prohibiting the free exercise -

Can We Save Video Game Journalism? Can Grass Roots Media Contribute with a More Critical Perspective to Contemporary Video Game Coverage?

Fall 08 Can We Save Video Game Journalism? Can grass roots media contribute with a more critical perspective to contemporary video game coverage? Author: Alejandro Soler Supervisor: Patrick Prax MASTERS THESIS: TWO YEARS MASTERS THESIS | DEPARTMENT OF INFORMATICS AND MEDIA | MEDIA & COMMUNICATION STUDIES UPPSALA UNIVERSITY | SPRING 2014 Abstract Video game journalism has been accused for lack in journalistic legitimacy for decades. The historical relation between video game journalists and video game publishers has always been problematic from an objective point of view, as publishers have the power to govern and dictate journalistic coverage by withdrawing financial funding and review material. This has consequently lead to lack in journalistic legitimacy when it comes to video game coverage. However, as the grass roots media movement gained popularity and attention in the mid 2000s, a new more direct and personal way of coverage became evident. Nowadays, grass roots media producers operate within the same field of practice as traditional journalists and the difference between entertainment and journalism has become harder than ever to distinguish. The aim of this master thesis is to discover if grass roots media is more critical than traditional video game journalism regarding industry coverage. The study combines Communication Power theory, Web 2.0 and Convergence Culture, as well as Alternative Media and Participatory Journalistic theory, to create an interdisciplinary theoretical framework. The theoretical framework also guides our choice in methodology as a grounded theory study, where the aim of analysis is to present or discover a new theory or present propositions grounded in our analysis. To reach this methodological goal, 10 different grass roots media producers were interviewed at 6 different occasions. -

Fake News and Related Concepts: Definitions and Recent Research Development

Contemporary Management Research Pages 145-174, Vol. 16, No. 3, 2020 doi:10.7903/cmr.20677 Fake News and Related Concepts: Definitions and Recent Research Development Chih-Chien Wang Graduate Institute of Information Management, National Taipei University, Taiwan E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Fake news is an emerging field of research that attracts much attention from academic communities as well as mass media practitioners. However, the concept of fake news is still ambiguous, and the boundary between the definition of fake news and other relative concepts, such as news satire, yellow journalism, junk news, pseudo- news, hoax news, propaganda news, advertorial, false information, fake information, misinformation, disinformation, mal-information, alternative fact, and post-truth is blurred. The present study aims to identify the meanings of fake news and other related concepts, and explore the recent trend of research on them. By searching the journals listed in the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) and Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-Expanded) database, the present study found 387 articles on fake news. Through analyzing these articles, the present study maps the trend and reveals the highly influential research articles, as well as theories and concepts that are used. The results may provide fundamental insights into the development of research on fake news in recent years. Keywords: Fake news, False news, Disinformation, Misinformation, Bibliometric analysis INTRODUCTION The advancement and popularity of the Internet have enabled people to obtain and distribute news messages quickly and ubiquitously. People now use mobile phones and social media to obtain news messages. (Chiang, Wu, & Yang, 2019). -

“Fake News” Is Not Simply False Information: A

ABSXXX10.1177/0002764219878224American Behavioral ScientistMolina et al. 878224research-article2019 Article American Behavioral Scientist 1 –33 “Fake News” Is Not Simply © 2019 SAGE Publications Article reuse guidelines: False Information: A Concept sagepub.com/journals-permissions https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764219878224DOI: 10.1177/0002764219878224 Explication and Taxonomy of journals.sagepub.com/home/abs Online Content Maria D. Molina1, S. Shyam Sundar1, Thai Le1, and Dongwon Lee1 Abstract As the scourge of “fake news” continues to plague our information environment, attention has turned toward devising automated solutions for detecting problematic online content. But, in order to build reliable algorithms for flagging “fake news,” we will need to go beyond broad definitions of the concept and identify distinguishing features that are specific enough for machine learning. With this objective in mind, we conducted an explication of “fake news” that, as a concept, has ballooned to include more than simply false information, with partisans weaponizing it to cast aspersions on the veracity of claims made by those who are politically opposed to them. We identify seven different types of online content under the label of “fake news” (false news, polarized content, satire, misreporting, commentary, persuasive information, and citizen journalism) and contrast them with “real news” by introducing a taxonomy of operational indicators in four domains—message, source, structure, and network— that together can help disambiguate the nature of online news content. Keywords fake news, false information, misinformation, persuasive information “Fake news,” or fabricated information that is patently false, has become a major phe- nomenon in the context of Internet-based media. It has received serious attention in a variety of fields, with scholars investigating the antecedents, characteristics, and con- sequences of its creation and dissemination. -

Yellow Journalism- Assignment # 5

Name________________________________ Class____________Date__________ Yellow Journalism- Assignment # 5 The Spanish-American War is often referred to as the first "media war." During the 1890s, journalism that sensationalized—and sometimes even manufactured—dramatic events were a powerful force that helped start the US war with Spain. Led by newspaper owners William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, journalism of the 1890s used drama, romance, and exaggeration to sell millions of newspapers - it became known as yellow journalism. The term yellow journalism came from a popular New York World comic called "Hogan's Alley," which featured a yellow-dressed character named the "the yellow kid." Determined to compete with Pulitzer's World in every way, rival New York Journal owner William Randolph Hearst copied Pulitzer's sensationalist style and even hired "Hogan's Alley" artist R.F. Outcault away from the World. In response, Pulitzer commissioned another cartoonist to create a second yellow kid. Soon, the sensationalist press of the 1890s became a competition between the "yellow kids," and the journalistic style was coined "yellow journalism." Yellow journals like the New York Journal and the New York World relied on sensationalist headlines to sell newspapers. William Randolph Hearst understood that a war with Cuba would not only sell his papers, but also move him into a position of national prominence. From Cuba, Hearst's star reporters wrote stories designed to tug at the heartstrings of Americans. Horrific tales described the situation in Cuba - female prisoners, executions, valiant rebels fighting, and starving women and children figured in many of the stories that filled the newspapers. But it was the sinking of the battleship Maine in Havana Harbor that gave Hearst his big story - war. -

World War II Newsreels: the Legacy of Yellow Journalism

WORLD WAR II NEWSREELS : THE LEGACY OF YELLOW JOURNALISM By Jessica L. Szalay California State University, Fresno In January 1930, the regular movie-goer could experience flight in the award-winning Guggenheim plane, watch the Capitol Dome in Washington, D.C. go up in flames, let the 41st Annual Pasadena Tournament of Roses Parade pass by, be amazed by the marksmanship of a 13-year-old-girl splitting a playing card edgewise from 45 feet away, and ride on a Miami auto-coaster with other thrill seekers. 1 What a miraculous way to see the world, and all in the comfort of one’s local movie theater. This is just one example of the American newsreel, which provided the public with a visual representation of the news. From its introduction to the American people in the 1900s to its demise in the 1950s, the newsreel was a staple of American life. These ten-minute presentations with around eight subjects of newsworthy or interesting footage played in theaters twice a week before a feature film. 2 Five major newsreel companies – Paramount News, 20th Century Fox’s Movietone News, RKO-Pathé News, MGM’s News of the Day, and Universal Newsreel – capitalized on the success of showing a lineup of headlines, human-interest stories, and sports. The subjects varied from week to week until the 1940s, when the newsreel began to focus on one subject – World War II. The Universal Newsreel of March 1944, for example, opens with a flight that highlights the newsreel companies’ focus on World War II. “BLAST BERLIN BY DAYLIGHT” flashed across the screen as music played in the background.