Introduction Michael Hattaway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

\~~A L BEC~US Tes OUR LAND

Palestinian struggle: the real facts -see story page 6- • The following letter of protest was sent to President Nixon have been ordered to the coast of Lebanon, and that you on behalf of the 75 Socialist \Vorkers Party candidates for have placed on alert troops from the Eighth Infantry Division public office in 15 states. It was written by Paul Boutelle, in West Germany and the 82nd Airborne Division at Fort SWP vice-presidential candidate in 1968 and currently the Bragg, N. C. I remember the 82nd Airborne as the same SWP candidate for Congress from Harlem. Paul Boutelle division that President Johnson sent to Santo Domingo to has just returned from a fact-finding trip to the Middle East. crush the uprising there in 1965, and into Detroit in 1967 * * * to crush the revolt of the Black community. President Nixon: This is not a coincidence. The struggles of the Dominicans The Socialist Workers Party demands the immediate halt and Afro-Americans, like those of the Palestinians, are strug to all steps toward U.S. military intervention in the Jor gles of oppressed peoples to control their own affairs. danian civil war. The U.S. has no right whatsoever in The United States government's support for the reactionary, Jordan. Zionist regime in Israel and its support for King Hussein's People throughout the world are just beginning to learn slaughter of the Palestinian refugees is consistent with its the scope of the wholesale slaughter that is occurring in support to reactionary dictatorships throughout the world Jordan right now. We hold your administration and its from Cambodia and Vietnam to South Africa, Greece and imperialist policies responsible for the bloodbath being per Iran. -

Make We Merry More and Less

G MAKE WE MERRY MORE AND LESS RAY MAKE WE MERRY MORE AND LESS An Anthology of Medieval English Popular Literature An Anthology of Medieval English Popular Literature SELECTED AND INTRODUCED BY DOUGLAS GRAY EDITED BY JANE BLISS Conceived as a companion volume to the well-received Simple Forms: Essays on Medieval M English Popular Literature (2015), Make We Merry More and Less is a comprehensive anthology of popular medieval literature from the twel�h century onwards. Uniquely, the AKE book is divided by genre, allowing readers to make connec�ons between texts usually presented individually. W This anthology offers a frui�ul explora�on of the boundary between literary and popular culture, and showcases an impressive breadth of literature, including songs, drama, and E ballads. Familiar texts such as the visions of Margery Kempe and the Paston family le�ers M are featured alongside lesser-known works, o�en oral. This striking diversity extends to the language: the anthology includes Sco�sh literature and original transla�ons of La�n ERRY and French texts. The illumina�ng introduc�on offers essen�al informa�on that will enhance the reader’s enjoyment of the chosen texts. Each of the chapters is accompanied by a clear summary M explaining the par�cular delights of the literature selected and the ra�onale behind the choices made. An invaluable resource to gain an in-depth understanding of the culture ORE AND of the period, this is essen�al reading for any student or scholar of medieval English literature, and for anyone interested in folklore or popular material of the �me. -

The Theological Socialism of the Labour Church

‘SO PECULIARLY ITS OWN’ THE THEOLOGICAL SOCIALISM OF THE LABOUR CHURCH by NEIL WHARRIER JOHNSON A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Theology and Religion School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham May 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The thesis argues that the most distinctive feature of the Labour Church was Theological Socialism. For its founder, John Trevor, Theological Socialism was the literal Religion of Socialism, a post-Christian prophecy announcing the dawn of a new utopian era explained in terms of the Kingdom of God on earth; for members of the Labour Church, who are referred to throughout the thesis as Theological Socialists, Theological Socialism was an inclusive message about God working through the Labour movement. By focussing on Theological Socialism the thesis challenges the historiography and reappraises the significance of the Labour -

Spenser's Method of Grace in the Legends of Holiness, Temperance

Spenser’s Method of Grace in the Legends of Holiness, Temperance, and Chastity A thesis submitted to the Graduate School Valdosta State University in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in English in the Department of English of the College of Humanities and Social Science May 2020 Rachel A. Miller BA, The Baptist College of Florida, 2017 i © Copyright 2020 Rachel A. Miller All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT The knights Redcrosse, Guyon, and Scudamour from The Faerie Queene are tasked with quests that curiously do not depend on wit or strength. Rather, the quests depend on each knight’s virtue and his acceptance of grace, the supreme virtue for Spenser. Through the wanderings of each knight, Spenser shows that there is a method of grace fashioned specifically for each knight’s quest both physical and spiritual that always requires the knights to reject false images of grace in exchange for God’s true grace. Grace will not abandon Gloriana’s knights, but as Guyon and Scudamour’s stubborn rejection of this virtue teaches, when grace is rejected, divine harmony, the loving cooperation between God and humanity that Redcrosse glimpses at the end of his quest, will be broken and replaced with fear and all the vices that follow it. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I: INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………….1 Spenser’s World: The Faerie Queene’s Historical Context ..............................2 Chapter 2: WHEN A CLOWNISH YOUNG MAN SLAYS A DRAGON…………..13 Redcrosse Receives His Calling………………………………………………13 Discovering Truth……………………………………………………………..16 -

Ingo Berensmeyer Literary Culture in Early Modern England, 1630–1700

Ingo Berensmeyer Literary Culture in Early Modern England, 1630–1700 Ingo Berensmeyer Literary Culture in Early Modern England, 1630–1700 Angles of Contingency This book is a revised translation of “Angles of Contingency”: Literarische Kultur im England des siebzehnten Jahrhunderts, originally published in German by Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen 2007, as vol. 39 of the Anglia Book Series. ISBN 978-3-11-069130-6 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-069137-5 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-069140-5 DOI https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110691375 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020934495 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available from the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. ©2020 Ingo Berensmeyer, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com. Cover image: Jan Davidszoon de Heem, Vanitas Still Life with Books, a Globe, a Skull, a Violin and a Fan, c. 1650. UtCon Collection/Alamy Stock Photo. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Preface to the Revised Edition This book was first published in German in 2007 as volume 39 of the Anglia Book Series. In returning to it for this English version, I decided not simply to translate but to revise it thoroughly in order to correct mistakes, bring it up to date, and make it a little more reader-friendly by discarding at least some of its Teutonic bag- gage. -

The Oxford Companion to English Literature, 6Th Edition

e cabal, from the Hebrew word qabbalah, a secret an elderly man. He is said by *Bede to have been an intrigue of a sinister character formed by a small unlearned herdsman who received suddenly, in a body of persons; or a small body of persons engaged in vision, the power of song, and later put into English such an intrigue; in British history applied specially to verse passages translated to him from the Scriptures. the five ministers of Charles II who signed the treaty of The name Caedmon cannot be explained in English, alliance with France for war against Holland in 1672; and has been conjectured to be Celtic (an adaptation of these were Clifford, Arlington, *Buckingham, Ashley the British Catumanus). In 1655 François Dujon (see SHAFTESBURY, first earl of), and Lauderdale, the (Franciscus Junius) published at Amsterdam from initials of whose names thus arranged happened to the unique Bodleian MS Junius II (c.1000) long scrip form the word 'cabal' [0£D]. tural poems, which he took to be those of Casdmon. These are * Genesis, * Exodus, *Daniel, and * Christ and Cade, Jack, Rebellion of, a popular revolt by the men of Satan, but they cannot be the work of Caedmon. The Kent in June and July 1450, Yorkist in sympathy, only work which can be attributed to him is the short against the misrule of Henry VI and his council. Its 'Hymn of Creation', quoted by Bede, which survives in intent was more to reform political administration several manuscripts of Bede in various dialects. than to create social upheaval, as the revolt of 1381 had attempted. -

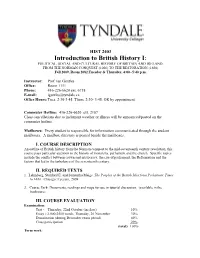

Introduction to British History I

HIST 2403 Introduction to British History I: POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND, FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST (1066) TO THE RESTORATION (1660) Fall 2009, Room 2082,Tuesday & Thursday, 4:00--5:40 p.m. Instructor: Prof. Ian Gentles Office: Room 1111 Phone: 416-226-6620 ext. 6718 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tues. 2:30-3:45, Thurs. 2:30- 3:45, OR by appointment Commuter Hotline: 416-226-6620 ext. 2187 Class cancellations due to inclement weather or illness will be announced/posted on the commuter hotline. Mailboxes: Every student is responsible for information communicated through the student mailboxes. A mailbox directory is posted beside the mailboxes. I. COURSE DESCRIPTION An outline of British history from the Norman conquest to the mid-seventeenth century revolution, this course pays particular attention to the history of monarchy, parliament and the church. Specific topics include the conflict between crown and aristocracy, the rise of parliament, the Reformation and the factors that led to the turbulence of the seventeenth century. II. REQUIRED TEXTS 1. Lehmberg, Stanford E. and Samantha Meigs. The Peoples of the British Isles from Prehistoric Times to 1688 . Chicago: Lyceum, 2009 2. Course Pack: Documents, readings and maps for use in tutorial discussion. (available in the bookstore) III. COURSE EVALUATION Examination : Test - Thursday, 22nd October (in class) 10% Essay - 2,000-2500 words, Thursday, 26 November 30% Examination (during December exam period) 40% Class participation 20% (total) 100% Term work : a. You are expected to attend the tutorials, preparing for them through the lectures and through assigned reading. -

From Chaucer to Tennyson by Henry A. Beers</H1>

From Chaucer to Tennyson by Henry A. Beers From Chaucer to Tennyson by Henry A. Beers Juliet Sutherland, Sjaani and PG Distributed Proofreaders Chautauqua Reading Circle Literature FROM CHAUCER TO TENNYSON WITH TWENTY-NINE PORTRAITS AND SELECTIONS FROM THIRTY AUTHORS. BY page 1 / 403 HENRY A. BEERS _Professor of English Literature in Yale University_. [Illustration] PREFACE. In so brief a history of so rich a literature, the problem is how to get room enough to give, not an adequate impression--that is impossible--but any impression at all of the subject. To do this I have crowded out every thing but _belles lettres_. Books in philosophy, history, science, etc., however important in the history of English thought, receive the merest incidental mention, or even no mention at all. Again, I have omitted the literature of the Anglo-Saxon period, which is written in a language nearly as hard for a modern Englishman to read as German is, or Dutch. Caedmon and Cynewulf are no more a part of English literature than Vergil and Horace are of Italian. I have also left out the vernacular literature of the Scotch before the time of Burns. Up to the date of the union Scotland was a separate kingdom, and its literature had a development independent of the English, though parallel with it. In dividing the history into periods, I have followed, with some modifications, the divisions made by Mr. Stopford Brooke in his excellent little _Primer of English Literature_. A short reading course page 2 / 403 is appended to each chapter. HENRY A. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

FWWH Revised Songbook ―This Camp Was Built to Music Therefore Built Forever

FWWH Revised Songbook Revised Summer 2011 ―This camp was built to music therefore built forever‖ These are the songs sung by Four Winds and Westward Ho campers – songs that have expressed their interests and ideals through the years. As you sing the songs again, may they recall memories of sunny days, and some misty and rainy ones too, of sailing on sparkling blue water, of cantering along leafy trails, of exploring the beach when the tide is out. May these songs remind you of unexpected adventure, and of friendships formed through the sharing of Summer days, working and playing together. 1 Index of songs A Gypsy‘s Life…………………………………………………….7 A Junior Song……………………………………………………..7 A Walking Song………………………………….…….………….8 Across A Thousand Miles of Sea…………..………..…………….8 Ah, Lovely Meadows…………………………..……..…………...9 All Hands On Deck……………………………………..……..…10 Another Fall…………………………………...…………………10 The Banks of the Sacramento…………………………………….…….12 Big Foot………………………………………..……….………………13 Bike Song……………………………………………………….…..…..14 Blow the Man Down…………………………………………….……...14 Blowin‘ In the Wind…………………………………………………....15 Boy‘s Grace…………………………………………………………….16 Boxcar……………………………………………………….…..……..16 Canoe Round…………………………………………………...………17 Calling Out To You…………………………………………………….17 Canoe Song……………………………………………………………..18 Canoeing Song………………………………………………………….18 Cape Anne………………………………………………...……………19 Carlyn…………………………………………………………….…….20 Changes………………………………………………………………...20 Christmas Night………………………………………………………...21 Christmas Song…………………………………………………………21 The Circle Game……………………………………………………..…22 -

Shakespeare and Hospitality

Shakespeare and Hospitality This volume focuses on hospitality as a theoretically and historically cru- cial phenomenon in Shakespeare’s work with ramifications for contempo- rary thought and practice. Drawing a multifaceted picture of Shakespeare’s numerous scenes of hospitality—with their depictions of greeting, feeding, entertaining, and sheltering—the collection demonstrates how hospital- ity provides a compelling frame for the core ethical, political, theological, and ecological questions of Shakespeare’s time and our own. By reading Shakespeare’s plays in conjunction with contemporary theory as well as early modern texts and objects—including almanacs, recipe books, hus- bandry manuals, and religious tracts—this book reimagines Shakespeare’s playworld as one charged with the risks of hosting (rape and seduction, war and betrayal, enchantment and disenchantment) and the limits of gen- erosity (how much can or should one give the guest, with what attitude or comportment, and under what circumstances?). This substantial volume maps the terrain of Shakespearean hospitality in its rich complexity, offering key historical, rhetorical, and phenomenological approaches to this diverse subject. David B. Goldstein is Associate Professor of English at York University, Canada. Julia Reinhard Lupton is Professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of California, Irvine. Routledge Studies in Shakespeare 1 Shakespeare and Philosophy 10 Embodied Cognition and Stanley Stewart Shakespeare’s Theatre The Early Modern 2 Re-playing Shakespeare in Asia Body-Mind Edited by Poonam Trivedi and Edited by Laurie Johnson, Minami Ryuta John Sutton, and Evelyn Tribble 3 Crossing Gender in Shakespeare Feminist Psychoanalysis and the 11 Mary Wroth and Difference Within Shakespeare James W. -

Worlds Trodden and Untrodden: Political Disillusionment, Literary Displacement, and the Conflicted Publicity of British Romanticism

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: WORLDS TRODDEN AND UNTRODDEN: POLITICAL DISILLUSIONMENT, LITERARY DISPLACEMENT, AND THE CONFLICTED PUBLICITY OF BRITISH ROMANTICISM Joseph E. Byrne, Doctor of Philosophy, 2013 Dissertation directed by: Professor Neil Fraistat, Department of English This study focuses on four first-generation British Romantic writers and their misadventures in the highly-politicized public sphere of the 1790s, which was riven by class conflict and media war. I argue that as a result of their negative experiences with publicity, these writers—William Wordsworth, William Godwin, Mary Wollstonecraft, and William Blake—recoiled from the pressures of public engagement and developed in reaction a depoliticized aesthetic program aligned with various forms of privacy. However, a “spectral” form of publicity haunts the subsequent works of these writers, which troubles and complicates the traditional identification of Romanticism with privacy. All were forced, in different ways, to negotiate the discursive space between privacy and publicity, and this effort inflected their ideas concerning literature. Thus, in sociological terms, British Romantic literature emerged not from the private sphere but rather from the inchoate space between privacy and publicity. My understanding of both privacy and publicity is informed by Jürgen Habermas’s well-known model of the British public sphere in the eighteenth century. However, I broaden the discussion to include other models of publicity, such as those elaborated by feminist and Marxist critics. In my discussion of class conflict in late- eighteenth-century Britain, I make use of the tools of class analysis, hegemony theory, and ideology critique, as used by new historicist literary critics. To explain media war in the 1790s, I utilize the media theory of Raymond Williams, particularly his conception of media as “material social practice.” All the writers in this study were profoundly engaged in the class conflict, media war, and politicized publicity of the British 1790s.