Download in Portable Document Format

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abundance and Community Composition of Arboreal Spiders: the Relative Importance of Habitat Structure

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Juraj Halaj for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Entomology presented on May 6, 1996. Title: Abundance and Community Composition of Arboreal Spiders: The Relative Importance of Habitat Structure. Prey Availability and Competition. Abstract approved: Redacted for Privacy _ John D. Lattin, Darrell W. Ross This work examined the importance of structural complexity of habitat, availability of prey, and competition with ants as factors influencing the abundance and community composition of arboreal spiders in western Oregon. In 1993, I compared the spider communities of several host-tree species which have different branch structure. I also assessed the importance of several habitat variables as predictors of spider abundance and diversity on and among individual tree species. The greatest abundance and species richness of spiders per 1-m-long branch tips were found on structurally more complex tree species, including Douglas-fir, Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirbel) Franco and noble fir, Abies procera Rehder. Spider densities, species richness and diversity positively correlated with the amount of foliage, branch twigs and prey densities on individual tree species. The amount of branch twigs alone explained almost 70% of the variation in the total spider abundance across five tree species. In 1994, I experimentally tested the importance of needle density and branching complexity of Douglas-fir branches on the abundance and community structure of spiders and their potential prey organisms. This was accomplished by either removing needles, by thinning branches or by tying branches. Tying branches resulted in a significant increase in the abundance of spiders and their prey. Densities of spiders and their prey were reduced by removal of needles and thinning. -

Higher-Level Phylogenetics of Linyphiid Spiders (Araneae, Linyphiidae) Based on Morphological and Molecular Evidence

Cladistics Cladistics 25 (2009) 231–262 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2009.00249.x Higher-level phylogenetics of linyphiid spiders (Araneae, Linyphiidae) based on morphological and molecular evidence Miquel A. Arnedoa,*, Gustavo Hormigab and Nikolaj Scharff c aDepartament Biologia Animal, Universitat de Barcelona, Av. Diagonal 645, E-8028 Barcelona, Spain; bDepartment of Biological Sciences, The George Washington University, Washington, DC 20052, USA; cDepartment of Entomology, Natural History Museum of Denmark, Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen, Universitetsparken 15, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark Accepted 19 November 2008 Abstract This study infers the higher-level cladistic relationships of linyphiid spiders from five genes (mitochondrial CO1, 16S; nuclear 28S, 18S, histone H3) and morphological data. In total, the character matrix includes 47 taxa: 35 linyphiids representing the currently used subfamilies of Linyphiidae (Stemonyphantinae, Mynogleninae, Erigoninae, and Linyphiinae (Micronetini plus Linyphiini)) and 12 outgroup species representing nine araneoid families (Pimoidae, Theridiidae, Nesticidae, Synotaxidae, Cyatholipidae, Mysmenidae, Theridiosomatidae, Tetragnathidae, and Araneidae). The morphological characters include those used in recent studies of linyphiid phylogenetics, covering both genitalic and somatic morphology. Different sequence alignments and analytical methods produce different cladistic hypotheses. Lack of congruence among different analyses is, in part, due to the shifting placement of Labulla, Pityohyphantes, -

Distribution of Spiders in Coastal Grey Dunes

kaft_def 7/8/04 11:22 AM Pagina 1 SPATIAL PATTERNS AND EVOLUTIONARY D ISTRIBUTION OF SPIDERS IN COASTAL GREY DUNES Distribution of spiders in coastal grey dunes SPATIAL PATTERNS AND EVOLUTIONARY- ECOLOGICAL IMPORTANCE OF DISPERSAL - ECOLOGICAL IMPORTANCE OF DISPERSAL Dries Bonte Dispersal is crucial in structuring species distribution, population structure and species ranges at large geographical scales or within local patchily distributed populations. The knowledge of dispersal evolution, motivation, its effect on metapopulation dynamics and species distribution at multiple scales is poorly understood and many questions remain unsolved or require empirical verification. In this thesis we contribute to the knowledge of dispersal, by studying both ecological and evolutionary aspects of spider dispersal in fragmented grey dunes. Studies were performed at the individual, population and assemblage level and indicate that behavioural traits narrowly linked to dispersal, con- siderably show [adaptive] variation in function of habitat quality and geometry. Dispersal also determines spider distribution patterns and metapopulation dynamics. Consequently, our results stress the need to integrate knowledge on behavioural ecology within the study of ecological landscapes. / Promotor: Prof. Dr. Eckhart Kuijken [Ghent University & Institute of Nature Dries Bonte Conservation] Co-promotor: Prf. Dr. Jean-Pierre Maelfait [Ghent University & Institute of Nature Conservation] and Prof. Dr. Luc lens [Ghent University] Date of public defence: 6 February 2004 [Ghent University] Universiteit Gent Faculteit Wetenschappen Academiejaar 2003-2004 Distribution of spiders in coastal grey dunes: spatial patterns and evolutionary-ecological importance of dispersal Verspreiding van spinnen in grijze kustduinen: ruimtelijke patronen en evolutionair-ecologisch belang van dispersie door Dries Bonte Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor [Ph.D.] in Sciences Proefschrift voorgedragen tot het bekomen van de graad van Doctor in de Wetenschappen Promotor: Prof. -

Landscape-Scale Connections Between the Land Use, Habitat Quality and Ecosystem Goods and Services in the Mureş/Maros Valley

TISCIA monograph series Landscape-scale connections between the land use, habitat quality and ecosystem goods and services in the Mureş/Maros valley Edited by László Körmöczi Szeged-Arad 2012 Two countries, one goal, joint success! Landscape-scale connections between the land use, habitat quality and ecosystem goods and services in the Mureş/Maros valley TISCIA monograph series 1. J. Hamar and A. Sárkány-Kiss (eds.): The Maros/Mureş River Valley. A Study of the Geography, Hydrobiology and Ecology of the River and its Environment, 1995. 2. A. Sárkány-Kiss and J. Hamar (eds.): The Criş/Körös Rivers’ Valleys. A Study of the Geography, Hydrobiology and Ecology of the River and its Environment, 1997. 3. A. Sárkány-Kiss and J. Hamar (eds.): The Someş/Szamos River Valleys. A Study of the Geography, Hydrobiology and Ecology of the River and its Environment, 1999. 4. J. Hamar and A. Sárkány-Kiss (eds.): The Upper Tisa Valley. Preparatory Proposal for Ramsar Site Designation and an Ecological Background, 1999. 5. L. Gallé and L. Körmöczi (eds.): Ecology of River Valleys, 2000. 6. Sárkány-Kiss and J. Hamar (eds.): Ecological Aspects of the Tisa River Basin, 2002. 7. L. Gallé (ed.): Vegetation and Fauna of Tisza River Basin, I. 2005. 8. L. Gallé (ed.): Vegetation and Fauna of Tisza River Basin, II. 2008. 9. L. Körmöczi (ed.): Ecological and socio-economic relations in the valleys of river Körös/Criş and river Maros/Mureş, 2011. 10. L. Körmöczi (ed.): Landscape-scale connections between the land use, habitat quality and ecosystem goods and services in the Mureş/Maros valley, 2012. -

196 Arachnology (2019)18 (3), 196–212 a Revised Checklist of the Spiders of Great Britain Methods and Ireland Selection Criteria and Lists

196 Arachnology (2019)18 (3), 196–212 A revised checklist of the spiders of Great Britain Methods and Ireland Selection criteria and lists Alastair Lavery The checklist has two main sections; List A contains all Burach, Carnbo, species proved or suspected to be established and List B Kinross, KY13 0NX species recorded only in specific circumstances. email: [email protected] The criterion for inclusion in list A is evidence that self- sustaining populations of the species are established within Great Britain and Ireland. This is taken to include records Abstract from the same site over a number of years or from a number A revised checklist of spider species found in Great Britain and of sites. Species not recorded after 1919, one hundred years Ireland is presented together with their national distributions, before the publication of this list, are not included, though national and international conservation statuses and syn- this has not been applied strictly for Irish species because of onymies. The list allows users to access the sources most often substantially lower recording levels. used in studying spiders on the archipelago. The list does not differentiate between species naturally Keywords: Araneae • Europe occurring and those that have established with human assis- tance; in practice this can be very difficult to determine. Introduction List A: species established in natural or semi-natural A checklist can have multiple purposes. Its primary pur- habitats pose is to provide an up-to-date list of the species found in the geographical area and, as in this case, to major divisions The main species list, List A1, includes all species found within that area. -

Zoologica Poloniae

ZOOLOGICA POLONIAE 2015 VOL. 60 FASC. 1-1 ISSN 0044-510X LUBLIN 2015 ZOOLOGICA POLONIAE ARCHIVUM SOCIETATIS ZOOLOGORUM POLONIAE VOL. 60 FASC. 1-1 2015 LUBLIN 2015 POLAND Zoologica Poloniae in open access http://www.degruyter.com/view/j/zoop http://www.umcs.pl/pl/zoologica-poloniae,11696.htm International scientific journal founded by Jarosław Wiącek Zakład Ochrony Przyrody Dept. of Biology and Biotechnology UMCS Lublin © Copyright by Polskie Towarzystwo Zoologiczne Wrocław 2015 ISSN 0044-510X PRINTED IN POLAND Opracowanie do druku: True Colours s.c., ul. I Armii WP 5/2, 20-078 Lublin, www.tcolours.com Nakład: 200 Zdjęcie na pierwszej stronie okładki: fot. M. Piskorski INDEX Łukasz Dawidowicz CONFIRMATION OF THE OCCURRENCE OF THYRIS FENESTRELLA (SCOPOLI, 1763) (LEPIDOPTERA: THYRIDIDAE) IN POLAND AND REMARKS ABOUT ITS BIOLOGY .....5 Grzegorz Gryziak, Grzegorz Makulec BRACHYCHTHONIUS HIRTUS (MORITZ, 1976) AND SUBIASELLA (LALMOPPIA) EUROPAEA (MAHUNKA, 1982) – TWO NEW SPECIES OF ORIBATID MITES (ACARI: ORIBATIDA) TO POLISH FAUNA AND TWO OTHER SPECIES NEW TO THE MAZOVIAN REGION WITHIN POLAND.......................................................................................11 Anna Hirna SPECIMENS OF SPIDER FAUNA FROM UKRAINE IN THE COLLECTION OF THE MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY, WROCLAW UNIVERSITY (ACCORDING TO THE COLLECTION OF STANISŁAW PILAWSKI AND KAZIMIERZ PETRUSEWICZ) .................15 Katarzyna Wołczuk, Teresa Napiórkowska, Robert Socha ANATOMICAL, HISTOLOGICAL AND HISTOCHEMICAL STUDIES OF THE ALIMENTARY CANAL OF MONKEY GOBY NEOGOBIUS FLUVIATILIS (Pallas, 1814) ...35 Maciej Filipiuk & Marcin Polak DISTRIBUTION AND HABITAT PREFERENCES OF EURASIAN BITTERN BOTAURUS STELLARIS AT NATURAL LAKES OF ŁĘCZNA–WŁODAWA LAKELAND ............................51 Michał Piskorski BAT FAUNA OF THE POLESKI NATIONAL PARK AND SOME ADJOINING AREAS .........65 Zoologica Poloniae (2015) 60/1. -

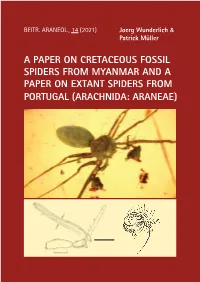

A Paper on Cretaceous Fossil Spiders from Myanmar and a Paper on Extant Spiders from Portugal (Arachnida: Araneae)

A PAPER ON CRETACEOUS FOSSIL BEITR. ARANEOL., 14 (2021) Joerg Wunderlich & (2021) Patrick Müller SPIDERS FROM MYANMAR AND A PAPER 14 ON EXTANT SPIDERS FROM PORTUGAL (ARACHNIDA: ARANEAE) A PAPER ON CRETACEOUS FOSSIL BEITR. ARANEOL., 14 (2021) SPIDERS FROM MYANMAR AND A BEITR. ARANEOL., PAPER ON EXTANT SPIDERS FROM Joerg Wunderlich (ed.) PORTUGAL (ARACHNIDA: ARANEAE) In this paper I (JW) try to round off the “trinity of fossil spider faunas” of three vanished worlds: of the Dominican, Baltic and Burmese (Kachin) ambers (from ca. 22, 45 and 100 (!) million years ago), which I treated in about a dozen volumes concerning the most diverse group of predatory animals of this planet, the spiders (Araneae). We treat in short the cannibalism of few Cretaceous spiders and provide notes on their orb webs. The focus of this study is the diverse fauna of the higher strata which is preserved in Burmese (Kachin) amber. Probably as the most IMPORTANT GENERAL RESULTS I found the Mid Cretaceous Burmese spider fauna to be at least as diverse as the fauna of today but composed by quite different groups and – in contrast to most groups of insects - by numerous (more than 60 %) extinct families of which apparently not a single genus survived. I identified and described ca. 300 species (55 families) of spiders in Burmese (Kachin) amber and estimate that probably more than three thousand spider species lived 100 million years ago in this ancient forest which was a tropical rain forest. What will be the number of spider species (and other animals) that survives the next 100 years in the endangered rain forest of today in Myanmar? A second IMPORTANT GENERAL RESULT: probably during the last 60-70 million years ancient spider groups of the “Middle age of the Earth” (the Mesozoicum) were largely displaced by derived members of the Orb weavers like the well- known Garden Spider (as well as other members of the superfamily Araneoidea) and by spiders like Jumping Spiders, House Spiders and Wolf Spiders (members of the “RTA-clade”) which are very diverse and frequent today. -

Die Spinnenfauna Des Göttinger Waldes (Arachnida: Araneida)

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Göttinger Naturkundliche Schriften Jahr/Year: 1997 Band/Volume: 4 Autor(en)/Author(s): Sührig Alexander Artikel/Article: Die Spinnenfauna des Göttinger Waldes (Arachnida: Araneida) 117-135 Göttinger Naturkundl iche Schriften 4, 1997: 117-135 © 1997 Biologische Schutzgemeinschaft Göttingen Die Spinnenfauna des Göttinger Waldes (Arachnida: Araneida) The spider fauna (Arachnida: Araneida) of the beech forest "Göttinger Wald" A lexander Sührig Summary In the "Göttinger Wald", a beechwood on limestone in southern Lower Saxony, 156 species (89 genera, 21 families) of spiders have been recorded to date. The distribution patterns of several selected species in a ca. 380 ha section of the study-area are described. Dominant forest-floor spi ders are Callobius claustrarius , C.oelotes terrestris, Histopona torpida , Diplocephalus picinus, Coelotes inermis, Pardosa lugubris , Saloca dicer os, Harpactea lepida and Apostenus fuscus. 1. EINLEITUNG Bereits 1980 wurden von einer Arbeitsgrup gegeben werden. Den für diese Untersu pe in der Abteilung Ökologie des II. Zoolo chung notwendigen Einsatz von Bodenfallen gischen Instituts der Universität Göttingen genehmigte die Bezirksregierung Braun Untersuchungen zur Bodenfauna eines schweig (503.2220/Gö vom 09.05.1994). Kalkbuchenwaldes begonnen, bei denen die Analyse der Streuzersetzung (Dekom position) als ein ökosystemarer Schlüssel 2. UNTERSUCHUNGSGEBIET UND prozess im Mittelpunkt des Interesses stand METHODEN bzw. steht (SCHAEFER 1989). Von 1979 bis Das ca. 380 ha große Untersuchungsgebiet 1985 wurde im Rahmen einer Diplomarbeit (SÜHRIG 1996) hegt im südniedersächsischen (St ippic h 1981) sowie einer Dissertation Bergland im südlichen Teil des Göttinger (S t ippic h 1986) auch die Spinnenfauna Waldes etwa 7 km südöstlich des Stadtkerns (Arachnida: Araneida) des Göttinger Waldes von Göttingen und gehört forstbetrieblich untersucht. -

A New Species of the Genus Pulchellodromus Wunderlich, 2012 (Aranei: Philodromidae) from Spain

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308890640 A new species of the genus Pulchellodromus Wunderlich, 2012 (Aranei: Philodromidae) from Spain Article in Arthropoda Selecta · October 2016 DOI: 10.15298/arthsel.25.3.09 CITATIONS READS 3 140 3 authors, including: Mykola Kovblyuk Nina Y. Polchaninova V.I. Vernadsky Crimean Federal University V. N. Karazin Kharkiv National University 53 PUBLICATIONS 209 CITATIONS 40 PUBLICATIONS 247 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: EDGG - Eurasian Dry Grassland Group View project Biological Bulletin of Bogdan Chmelnitskiy Melitopol State Pedagogical University View project All content following this page was uploaded by Nina Y. Polchaninova on 05 October 2016. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Arthropoda Selecta 25(3): 293–296 © ARTHROPODA SELECTA, 2016 A new species of the genus Pulchellodromus Wunderlich, 2012 (Aranei: Philodromidae) from Spain Íîâûé âèä ðîäà Pulchellodromus Wunderlich, 2012 (Aranei: Philodromidae) èç Èñïàíèè Zoya A. Kastrygina1, Mykola M. Kovblyuk1,2, Nina Yu. Polchaninova3 Ç.À. Êàñòðûãèíà1, Í.Ì. Êîâáëþê1,2, Í.Þ. Ïîë÷àíèíîâà3 1 V.I. Vernadsky Crimean Federal University, Yaltinskaya Str. 4, Simferopol 295007, Crimea. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] 2 T.I. Vyazemski Karadag Scientific Station – Nature Reserve of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Nauki Str., 24, Kurortnoe Vil., Feodosiya 298188, Crimea. 3 V.N. Karazin Kharkiv National University, 4, Svobody sq., Kharkiv 61022, Ukraine. E-mail: [email protected] 1 Крымский федеральный университет им. В.И. Вернадского, ул. Ялтинская 4, г. -

SRS News 66.Pub

www.britishspiders.org.uk S.R.S. News. No. 66 In Newsl. Br. arachnol. Soc. 117 Spider Recording Scheme News March 2010, No. 66 Editor: Peter Harvey; [email protected]@britishspiders.org.uk My thanks to those who have contributed to this issue. S.R.S. News No. 67 will be published in July 2010. Please send contributions by the end of May at the latest to Peter Harvey, 32 Lodge Lane, GRAYS, Essex, RM16 2YP; e-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Editorial Hillyard noted that it had been recorded at Edinburgh. This was not mapped, but probably refers to a record from As usual I am very grateful to all the contributors who have provided articles for this issue. Please keep the Lothian Wildlife Information Centre ‘Secret Garden providing articles. Survey’. The species was found in Haddington, to the Work on a Spider Recording Scheme website was east of Edinburgh and south of the Firth of Forth in delayed by hiccups in the OPAL grant process and the October 1995 (pers. comm. Bob Saville). These records timeslot originally set aside for the work has had to be appear on the National Biodiversity Network Gateway. reorganised. Work should now be completed by the end of D. ramosus is generally synanthropic and is common May this year. in gardens where it can be beaten from hedges and trees, As always many thanks are due to those Area especially conifers. However many peoples’ first Organisers, MapMate users and other recorders who have experience of this species will be of seeing it spread- provided their records to the scheme during 2009 and eagled on a wall (especially if the wall is whitewashed – early this year. -

Ekologie Pavouků a Sekáčů Na Specifických Biotopech V Lesích

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI Přírodovědecká fakulta Katedra ekologie a životního prostředí Ekologie pavouků a sekáčů na specifických biotopech v lesích Ondřej Machač DOKTORSKÁ DISERTAČNÍ PRÁCE Školitel: doc. RNDr. Mgr. Ivan Hadrián Tuf, Ph.D. Olomouc 2021 Prohlašuji, že jsem doktorskou práci sepsal sám s využitím mých vlastních či spoluautorských výsledků. ………………………………… © Ondřej Machač, 2021 Machač O. (2021): Ekologie pavouků a sekáčů na specifických biotopech v lesích s[doktorská di ertační práce]. Univerzita Palackého, Přírodovědecká fakulta, Katedra ekologie a životního prostředí, Olomouc, 35 s., v češtině. ABSTRAKT Pavoukovci jsou ekologicky velmi různorodou skupinou, obývají téměř všechny biotopy a často jsou specializovaní na specifický biotop nebo dokonce mikrobiotop. Mezi specifické biotopy patří také kmeny a dutiny stromů, ptačí budky a biotopy ovlivněné hnízděním kormoránů. Ve své dizertační práci jsem se zabýval ekologií společenstev pavouků a sekáčů na těchto specifických biotopech. V první studii jsme se zabývali společenstvy pavouků a sekáčů na kmenech stromů na dvou odlišných biotopech, v lužním lese a v městské zeleni. Zabývali jsme se také jednotlivými společenstvy na kmenech různých druhů stromů a srovnáním tří jednoduchých sběrných metod – upravené padací pasti, lepového a kartonového pásu. Ve druhé studii jsme se zabývali arachnofaunou dutin starých dubů za pomocí dvou sběrných metod (padací past v dutině a nárazová past u otvoru dutiny) na stromech v lužním lese a solitérních stromech na loukách a také srovnáním společenstev v dutinách na živých a odumřelých stromech. Ve třetí studii jsme se zabývali společenstvem pavouků zimujících v ptačích budkách v nížinném lužním lese a vlivem vybraných faktorů prostředí na jejich početnosti. Zabývali jsme se také znovuosídlováním ptačích budek pavouky v průběhu zimy v závislosti na teplotě a vlivem hnízdního materiálu v budce na početnosti a druhové spektrum pavouků. -

Annotated Checklist of the Spiders of Turkey

_____________Mun. Ent. Zool. Vol. 12, No. 2, June 2017__________ 433 ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE SPIDERS OF TURKEY Hakan Demir* and Osman Seyyar* * Niğde University, Faculty of Science and Arts, Department of Biology, TR–51100 Niğde, TURKEY. E-mails: [email protected]; [email protected] [Demir, H. & Seyyar, O. 2017. Annotated checklist of the spiders of Turkey. Munis Entomology & Zoology, 12 (2): 433-469] ABSTRACT: The list provides an annotated checklist of all the spiders from Turkey. A total of 1117 spider species and two subspecies belonging to 52 families have been reported. The list is dominated by members of the families Gnaphosidae (145 species), Salticidae (143 species) and Linyphiidae (128 species) respectively. KEY WORDS: Araneae, Checklist, Turkey, Fauna To date, Turkish researches have been published three checklist of spiders in the country. The first checklist was compiled by Karol (1967) and contains 302 spider species. The second checklist was prepared by Bayram (2002). He revised Karol’s (1967) checklist and reported 520 species from Turkey. Latest checklist of Turkish spiders was published by Topçu et al. (2005) and contains 613 spider records. A lot of work have been done in the last decade about Turkish spiders. So, the checklist of Turkish spiders need to be updated. We updated all checklist and prepare a new checklist using all published the available literatures. This list contains 1117 species of spider species and subspecies belonging to 52 families from Turkey (Table 1). This checklist is compile from literature dealing with the Turkish spider fauna. The aim of this study is to determine an update list of spider in Turkey.