'The "Perfyt Scyens" of the Map; a Study of the Meaning and Interpretation of Local Maps in Early Tudor England 1509-1547'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Axonometric (Isometric Projection)

AXONOMETRIC (ISOMETRIC PROJECTION) Representation Systems Isometric Into the ISOMETRIC PERSPECTIVE, the isometric axes form a 120º angle between one another Elevation Profile Plan Isometric Into the ISOMETRIC PERSPECTIVE, the isometric axes form a 120º angle between one another Front View Isometric Into the ISOMETRIC PERSPECTIVE, the isometric axes form a 120º angle between one another Front View Isometric Into the ISOMETRIC PERSPECTIVE, the isometric axes form a 120º angle between one another Front View Isometric Into the ISOMETRIC PERSPECTIVE, the isometric axes form a 120º angle between one another Front View Isometric Into the ISOMETRIC PERSPECTIVE, the isometric axes form a 120º angle between one another Front View Isometric Into the ISOMETRIC PERSPECTIVE, the isometric axes form a 120º angle between one another Front View Isometric Into the ISOMETRIC PERSPECTIVE, the isometric axes form a 120º angle between one another Front View Isometric Into the ISOMETRIC PERSPECTIVE, the isometric axes form a 120º angle between one another Front View Isometric Into the ISOMETRIC PERSPECTIVE, the isometric axes form a 120º angle between one another Front View Isometric Into the ISOMETRIC PERSPECTIVE, the isometric axes form a 120º angle between one another Front View Isometric Into the ISOMETRIC PERSPECTIVE, the isometric axes form a 120º angle between one another Front View Isometric Into the ISOMETRIC PERSPECTIVE, the isometric axes form a 120º angle between one another Front View Isometric Into the ISOMETRIC PERSPECTIVE, the isometric axes form a 120º angle between one another Front View Isometric Into the ISOMETRIC PERSPECTIVE, the isometric axes form a 120º angle between one another Front View Isometric Into the ISOMETRIC PERSPECTIVE, the isometric axes form a 120º angle between one another Front View Isometric Into the ISOMETRIC PERSPECTIVE, the isometric axes form a 120º angle between one another Front View Technical Drawing Name and Surname: Axonometric System Draw the AXONOMETRIC PERSPECTIVE of these pieces. -

Basic Engineering Drawings

Today’s Thoughts The thing that’s so wonderful about using beautiful, appropriate [CAD] tools is that they become an extension of you, your body, you fingertips, and your mind. They get out of the way and let you directly interact with the problem you are solving. Everyone’s tried to remove a screw without a screwdriver; a task quickly becomes impossible that otherwise would be trivial. — Luke Crawford Here is one of the few effective keys to the design problem — the ability of the designer to recognize as many of the constraints as possible — his willingness and enthusiasm for working within these constraints. Constraints of price, of size, of strength, of balance, of surface, of time and so forth. — Charles Eames Section Views ME 172 Outline • Full Section • Half Section • Offset Section • Broken-out Section • Revolved Section • Removed Section • Sectioning Problems • Sectioning Quiz A Section View Technical Drawing– by Giesecke Visualizing a Section View Technical Drawing– by Giesecke Visualizing a Section View Technical Drawing– by Giesecke A Cut Plane Line Technical Drawing– by Giesecke Full Section View Blueprint Reading Basics – by Warren Hammer Full Section View Technical Drawing– by Giesecke Correct Full Section View Technical Drawing– by Giesecke Correct Full Section View Technical Drawing– by Giesecke Correct Full Section View Technical Drawing– by Giesecke Sectioning Symbols Technical Drawing– by Giesecke Correct Sectioning Lines Technical Drawing– by Giesecke ProblemAligned Full with Section a Full Section Blueprint Reading -

English Coast Defences

ENGLISH COAST DEFENCES GEORGE CLINCH PART I ENGLISH COAST DEFENCES PREHISTORIC CAMPS Round the coast of England there are many prehistoric earthworks of great extent and strength. These fall generally under the heads of hill-top fortresses and promontory camps. The works comprised under the former head are so arranged as to take the greatest possible advantage of natural hill-tops, often of large size. On the line where the comparatively level top developed into a more or less precipitous slope a deep ditch was dug, and the earth so removed was in most cases thrown outwards so as to form a rampart which increased the original difficulties of the sloping hill-side. The latter type of earthwork, called promontory camps from their natural conformation, were strengthened by the digging of a deep ditch, so as to cut off the promontory from the main table-land from which it projected, and in some cases the sides of the camp were made more precipitous by artificial scarping. An examination of these types of earthworks leads to the conclusion that they were probably tribal enclosures for the safe-guarding of cattle, etc.; that, strictly speaking, they were not military works at all, and, in any case, had no relation to national defence against enemies coming over-sea. One finds in different parts of the country a prevalent tradition that the Romans occupied the more ancient British hill-top strongholds, and the name “Caesar‟s Camp” is popularly applied to many of them. If such an occupation really took place it was, in all probability, only of a temporary character. -

Drawing the “Boundaries”, the Start of an Urban Planning Project

Geographia Technica, Vol. 12, Issue 2, 2017, pp 73 to 81 DRAWING THE “BOUNDARIES”, THE START OF AN URBAN PLANNING PROJECT Jordi GOMIS1, Carlos TURÓN DOI: 10.21163/GT_2017.122.07 ABSTRACT: The graphic representation of the boundaries of urban planning areas is a sufficiently important element of the representation of urban planning as not to allow the slightest hint of doubt or imprecision to arise in regard to the dividing lines it indicates. It can include everything from the growth limit of the urban land as a whole to small inner areas of the city subject to improvement, renovation or change of planning conditions. It is this first concept that the town planner must include/draw on his working plan to begin his task. Throughout the history of urban planning, this first “boundary” has been represented in various ways using different graphic and/or visual mechanisms. This article presents a journey through the history of the resources used by technicians for their representation and their evolution. Key-words: Graphic representation, Technical drawing, Urban Planning, City drawing, Urbanism. 1. INTRODUCTION The demarcation of geographical, territorial, municipal, regional, etc. areas has never been a problem dissociated from society. Since ancient times the specification of geographic boundaries and limits of influence has occupied and preoccupied people. “Boundaries” and “frontiers” have always given rise to disputes that people have attempted to resolve and settle, sometimes graphically, many others, unfortunately, through the use of force. Various inventories of land, people, property, crops, etc. were made ever since ancient times to inform kings and noblemen of the quantity and quality of their belongings and properties. -

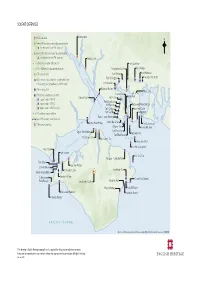

Solent Defences Map.Ai

SOLENT DEFENCES Southampton Medieval castle N Henry VIII circular or centrally planned castle ( modernised in the 19th century) Henry VIII castle influenced by angle bastion ( modernised in the 19th century) Netley Castle 16th-century bastioned enceinte Fort Southwick 17th–18th-century bastioned enceinte Portchester Castle Fort Widley 17th-century fort Fort Nelson Fort Purbrook S Fort Wallington Farlington Redoubt 18th-century bastioned fort, modernised in the O U T 19th-century and operational in WW1 and 2 H Fort Fareham A M P Bungalow Battery 19th-century fort T O Hilsea Lines N Charles Fort 19th-century battery or sea fort James Fort Calshot Castle Fort Elson ( operational in WW1) W A T Fort Brockhurst ( operational in WW2) E R Fort Rowner Portsmouth Point Battery ( operational in WW1 and 2) Fort Grange Southsea Castle 19th-century bastioned line Fort Gomer Lumps Fort Brown Down Battery Late 19th-century boom defence Stokes Bay Lines 20th-century defence Stone Point Battery Fort Cumberland Gilkicker Fort Eastney Batteries Fort Monckton Egypt Point Battery Spitbank Fort Fort Blockhouse West Cowes Fort East Cowes Fort SPITHEAD N T L E Horse Sand Fort S O E T H No Man’s Land Fort Hurst Castle Fort Victoria St Helen’s Fort Puckpool Mortar Battery Fort Albert Bouldner Battery Cliff End Battery Yarmouth Castle Bembridge Fort Warden Point Battery Golden Hill Fort Hatherwood Culver Point Battery Point Battery Carisbrooke Castle Sandown Fort Barrack Battery Redcliff Battery Freshwater Redoubt Yaverland Battery Needles Battery ENGLISH CHANNEL Based upon Ordnance Survey data. © Crown copyright 2006. All rights reserved. Licence no. -

19 Argyll-Street, Ryde, IW. Willliam F. MITCHELL. Head. M. 46. Marine Artist

1891 CENSUS: RG12/891. Folio 97. Page 34. Address: 19 Argyll-street, Ryde, IW. Willliam F. MITCHELL. Head. M. 46. Marine Artist Royal Navy. Fawley, Hants. (deaf from childhood) Elizabeth C. MITCHELL. Wife. M. 47. Lewes, Sussex. (deaf from childhood) Frederick W. G. MITCHELL. Son. 7. Southampton, Hants. Emily E. WATERHOUSE. Serv. S. 22. Cook Domestic Servant. Southampton, Hants. Louisa E. WATERHOUSE. Serv. S. 20. Housemaid Domestic Servant. Southampton, Hants. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 1898 KELLY’s DIRECTORY of Hampshire & Isle of Wight – page 409 MITCHELL William Frederick, Calshot Villa, 19 Argyll-street, Ryde, IW. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1901 CENSUS: RG13/1024. Folio 11. Page 13. Address: Calshot, Yelfs-road, Ryde, IW. William F. MITCHELL. Head. M. 56. Naval Artist (own acc at home). Calshot Castle, Hants. Elizabeth C. MITCHELL. Wife. M. 60. Stanmer, Sussex. Fredk. W. MITCHELL. Son. 17. Engineer Apprentice Locomotive. Southampton, Hants. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- In 1911 Elizabeth was living at “Calshot”, Yelf-road, Ryde, with her husband William, he was listed as a Marine Artist Own Account at home. Both of them were deaf and dumb, William from the age of 6 and Elizabeth from the age of 4. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ISLE OF WIGHT OBSERVER Saturday Feb 11th 1922, page 2. DEATH OF MRS. W. F. MITCHELL The death of the widow of the late Mr. W. Fred MITCHELL, the well-known Naval artist, formerly of Ryde, took place at her residence, 34 St. Michaels Place, Brighton, on Sunday, February 5th, in her 82nd year. The deceased lady had suffered for many years from rheumatism, nevertheless was always of a bright and happy disposition. She was a connection of an old Sussex family named WOODMAN. -

Fortress Study Group Library Catalogue

FSG LIBRARY CATALOGUE OCTOBER 2015 TITLE AUTHOR SOURCE PUBLISHER DATE PAGE COUNTRY CLASSIFICATION LENGTH "Gibraltar of the West Indies": Brimstone Hill, St Kitts Smith, VTC Fortress, no 6, 24-36 1990 West Indies J/UK/FORTRESS "Ludendorff" fortified group of the Oder-Warthe-Bogen front Kedryna, A & Jurga, R Fortress, no 17, 46-58 1993 Germany J/UK/FORTRESS "Other" coast artillery posts of southern California: Camp Haan, Berhow, MA CDSG News Volume 4, 1990 2 USA J/USA/CDSG 1 Camp Callan and Camp McQuaide Number 1, February 1990 100 Jahre Gotthard-Festung, 1885-1985 : Geschichte und Ziegler P GBC, Basel 1986 Switzerland B Bedeutung unserer Alpenfestung [100 years of the Gotthard Fortress, 1885-1985 : history and importance of our Alpine Fortress] 100 Jahre Gotthard-Festung, 1885-1985 : Geschichte und Ziegler P 1995 Switzerland B Bedeutung unserer Alpenfestung [100 years of the Gotthard Fortress, 1885-1985 : history and importance of our Alpine Fortress] 10thC castle on the Danube Popa, R Fortress, no 16, 16-24 1993 Bulgaria J/UK/FORTRESS 12-Inch Breech Loading Mortars Smith, BW CDSG Journal Volume 7, 1993 2 USA J/USA/CDSG 1 Issue 3, November 1993 13th Coast Artillery (Harbor Defense) Regiment Gaines, W CDSG Journal Volume 7, 1993 10 USA J/USA/CDSG 1 Issue 2, May 1993 14th Coast Artillery (Harbor Defense) Regiment, An Organizational Gaines, WC CDSG Journal Volume 9, 1995 17 USA J/USA/CDSG 2 History, The Issue 3, August 1995 16-Inch Batteries at San Francisco and The Evolution of The Smith B Coast Defense Journal 2001 68 USA J/USA/CDSG 2 Casemated 16-Inch Battery, The Volume 15, Issue 1, February 2001 180 Mm Coast Artillery Batteries Guarding Vladivostok,1932-1945 Kalinin, VI et al Coast Defense Journal 2002 25 Russia J/USA/CDSG 2 Part 2: Turret Batteries Volume 16, Issue 1, February 2002 180mm Coast Artillery Batteries Guarding Vladivostok, Russia, Kalinin, VI et al Coast Defense Journal 2001 53 Russia J/USA/CDSG 2 1932-1945: Part 1. -

Industrial Computer Graphics Technology

Industrial Computer Graphics Technology About the ProgrAm The Industrial Computer Graphics PAy Technology program provides The median annual wage for students with career-based drafters was $56,830 in May 2019. training in mechanical design using computer-aided Job outlook drafting/design technology. Employment of drafters is To provide the necessary projected to grow 0 percent from technical education base, the 2018 to 2028. Although drafters program also includes education will continue to work on technical and training in applied technical mathematics, engineering, drawing, and drawings and documents related geometric dimensioning and tolerance skills. Basic training in computer to the design of buildings, machines, technology is included to prepare students for the two-dimensional, and tools, new software programs three-dimensional and solid modeling computer-aided design technology are changing the nature of drafting in the program. All technical manufacturing and engineering design in work and how it is done. Those today's high-technology business and industry uses computer-based, with formal training in this computer-aided design technologies that integrate the design, engineering technology should have the and manufacturing design analysis, and manufacturing of complex products best job opportunities. and product parts, subassemblies, and assemblies into a single, technically coherent process. Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Outlook Handbook, The Industrial Computer Graphics Technology program provides the skills April 2020, Drafters, on the Internet at http://www.bls.gov/ooh/architecture-and- and knowledge required for entry-level employment in industrial drafting, engineering/drafters.htm computer-aided drafting, and mechanical design fields. Emphasis is placed on the applications, procedures and techniques of principles involved in industrial drafting and design techniques. -

The Elizabethan Court Day by Day--1591

1591 1591 At RICHMOND PALACE, Surrey. Jan 1,Fri New Year gifts; play, by the Queen’s Men.T Jan 1: Esther Inglis, under the name Esther Langlois, dedicated to the Queen: ‘Discours de la Foy’, written at Edinburgh. Dedication in French, with French and Latin verses to the Queen. Esther (c.1570-1624), a French refugee settled in Scotland, was a noted calligrapher and used various different scripts. She presented several works to the Queen. Her portrait, 1595, and a self- portrait, 1602, are in Elizabeth I & her People, ed. Tarnya Cooper, 178-179. January 1-March: Sir John Norris was special Ambassador to the Low Countries. Jan 3,Sun play, by the Queen’s Men.T Court news. Jan 4, Coldharbour [London], Thomas Kerry to the Earl of Shrewsbury: ‘This Christmas...Sir Michael Blount was knighted, without any fellows’. Lieutenant of the Tower. [LPL 3200/104]. Jan 5: Stationers entered: ‘A rare and due commendation of the singular virtues and government of the Queen’s most excellent Majesty, with the happy and blessed state of England, and how God hath blessed her Highness, from time to time’. Jan 6,Wed play, by the Queen’s Men. For ‘setting up of the organs’ at Richmond John Chappington was paid £13.2s8d.T Jan 10,Sun new appointment: Dr Julius Caesar, Judge of the Admiralty, ‘was sworn one of the Masters of Requests Extraordinary’.APC Jan 13: Funeral, St Peter and St Paul Church, Sheffield, of George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury (died 18 Nov 1590). Sheffield Burgesses ‘Paid to the Coroner for the fee of three persons that were slain with the fall of two trees that were burned down at my Lord’s funeral, the 13th of January’, 8s. -

Swiss Cottage, South Stoneham, Hants. William MITCHELL. Head

1881 CENSUS: RG11/1219. Folio 59. Page 5. Address: Swiss Cottage, South Stoneham, Hants. William MITCHELL. Head. Widr. 81. Commander Royal Navy Retired List. Chatham, Kent. William F. MITCHELL. Son. Unm. 36. Marine Artist P2. Calshot Castle, Hants. Julia MITCHELL. Dau-in-law. Mar. 25. Sheerness, Kent. Letitia F. V. MITCHELL. Gr/dau. 2. Tricomalee, Ceylon. Charlotte M. HARPER. Visitor. Unm. 18. Sheerness, Kent.Kent. Teresa GOSLIN. Serv. Unm. 32. Cook Servant Domestic. Southampton, Hants. Emma WEBB. Serv. Unm. 22. Nurse Servant Domestic. Mitcheldever, Hants. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1891 CENSUS: RG12/891. Folio 97. Page 34. Address: 19 Argyll-street, Ryde, IW. Willliam F. MITCHELL. Head. M. 46. Marine Artist Royal Navy. Fawley, Hants. (deaf from childhood) Elizabeth C. MITCHELL. Wife. M. 47. Lewes, Sussex. (deaf from childhood) Frederick W. G. MITCHELL. Son. 7. Southampton, Hants. Emily E. WATERHOUSE. Serv. S. 22. Cook Domestic Servant. Southampton, Hants. Louisa E. WATERHOUSE. Serv. S. 20. Housemaid Domestic Servant. Southampton, Hants. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 1898 KELLY’s DIRECTORY of Hampshire & Isle of Wight – page 409 MITCHELL William Frederick, Calshot Villa, 19 Argyll-street, Ryde, IW. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1901 CENSUS: RG13/1024. Folio 11. Page 13. Address: Calshot, -

Hampshire Bus, Train and Ferry Guide 2014-2015

I I I I NDEX F LACES ERVED I I O P S To Newbury To Newbury To Tilehurst To Reading To Reading, To Reading To Wokingham I To Windsor I I Oxford and I and Reading I Bracknell 103 I Abbotts Ann. D3 Fyfield . D2 ABC D E F G H JI K Portsmouth & Southsea a . G8 the NorthI Three Mile I X2 I Adanac Park . D6 Wash Comon The Link I 194 Portsmouth Harbour a. G8 I Cross I Alderbury. B4 Glendene Caravan Park, Bashley . C8 104 2A I I Poulner . B7 Burghfield 2 I 72 I Alderholt . .A . A6 Godshill . B6 I I Pound Green . G1 Common I Aldermaston . G1 Godwinscroft . B8 u I 7 BERKSHIRE I 82 I Privett, Gosport . F8 103 Greenham I Aldershot a . K3 Golden Pot Inn . H3 I Inkpen 7 21 22 The Link Brimpton I Purbrook . G7 Ball Hill Aldermaston I I Allbrook . E5 Golf Course, Nr Alton . H3 Common I Beacon Crookham I PUBLIC TRANSPORT MAP OF I I h Allington . C3 Goodworth Clatford . D3 Wash 2 I t I I 194 a Alton a . H4 Gosport . G8 Quarley . D3 104 I 22 I P Water I 103 Spencers Wood I s Queen Alexander Hospital,Cosham. G7 2A I Great Hollands e Alton Hospital and Sports Centre . H4 Grange Park. F6 24 I I tl 21 The Link Bishopswood I a I s Amesbury . B3 Grateley . D3 Quetta Park . J3 7u Bishop’s Green I G X2 I a 21 22A I Broadlaying 23 Road Shops X2 I 194 C Ampfield . -

Technical Drafting and Mental Visualization in Interior Architecture Education Ali Riza Arslan Ali Riza [email protected]

International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning Volume 11 | Number 2 Article 15 July 2017 Technical Drafting and Mental Visualization in Interior Architecture Education Ali Riza Arslan [email protected] Sibel Seda Dazkir Georgia Southern University, [email protected] Recommended Citation Arslan, Ali Riza and Dazkir, Sibel Seda (2017) "Technical Drafting and Mental Visualization in Interior Architecture Education," International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning: Vol. 11: No. 2, Article 15. Available at: https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2017.110215 Technical Drafting and Mental Visualization in Interior Architecture Education Abstract We explored how beginning-level interior architecture students develop skills to create mental visualizations of three-dimensional objects and environments, how they develop their technical drawing skills, and whether or not physical and computer generated models aid this design process. We used interviews and observations to collect data. The findings provide an insight on what kind of difficulties students experience during their learning process and how they overcome those difficulties. The er sults of the study indicate that the students’ lack of skills in technical drawing and in creating 2D and 3D mental visualizations negatively influenced their design process. Using the existing body of literature, we discussed the findings and suggested teaching strategies to improve the learning process for the beginning-level interior architecture students. The findings of this study allowed us to have a better understanding of the student design and learning process. Keywords Interior architecture, interior design, technical drawing skills, mental visualization, computer aided design, architectural models IJ-SoTL, Vol. 11 [2017], No.