Journal of the Music & Entertainment Industry Educators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sf Best Cal Fall 2019

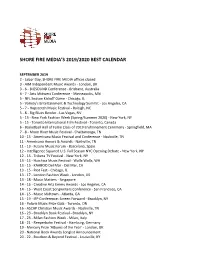

SHORE FIRE MEDIA’S 2019/2020 BEST CALENDAR SEPTEMBER 2019 2 - Labor Day, SHORE FIRE MEDIA offices closed 3 - AIM Independent Music Awards - London, UK 3 - 6 - BIGSOUND Conference - Brisbane, Australia 4 - 7 - Arts Midwest Conference - Minneapolis, MN 5 - NFL Season Kickoff Game - Chicago, IL 5 - Variety’s EntertainMent & Technology SumMit - Los Angeles, CA 5 - 7 - Hopscotch Music Festival - Raleigh, NC 5 - 8 - Big Blues Bender - Las Vegas, NV 5 - 13 - New York Fashion Week (Spring/Summer 2020) - New York, NY 5 - 15 - Toronto International Film Festival - Toronto, Canada 6 - Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2019 EnshrineMent Ceremony - Springfield, MA 7 - 8 - Moon River Music Festival - Chattanooga, TN 10 - 15 - AMericana Music Festival and Conference - Nashville, TN 11 - AMericana Honors & Awards - Nashville, TN 11 - 13 - Future Music Forum - Barcelona, Spain 12 - Intelligence Squared U.S. Fall Season NYC Opening Debate - New York, NY 12 - 15 - Tribeca TV Festival - New York, NY 13 - 14 - Huichica Music Festival - Walla Walla, WA 13 - 15 - KAABOO Del Mar - Del Mar, CA 13 - 15 - Riot Fest - Chicago, IL 13 - 17 - London Fashion Week - London, UK 13 - 18 - Music Matters - Singapore 14 - 15 - Creative Arts EmMy Awards - Los Angeles, CA 14 - 15 - West Coast Songwriters Conference - San Francisco, CA 14 - 15 - Music Midtown - Atlanta, GA 15 - 19 - IFP Conference: Screen Forward - Brooklyn, NY 16 - Polaris Music Prize Gala - Toronto, ON 16 - ASCAP Christian Music Awards - Nashville, TN 16 - 23 - Brooklyn Book Festival - Brooklyn, NY 17 - 23 -

Shore Fire Best Calendar 2018

SHORE FIRE MEDIA’S 2018 BEST CALENDAR FEBRUARY 2018 1 - Super Bowl Gospel Celebration - St. Paul, MN 3 - Directors Guild Awards - Los Angeles, CA 3 - NFL Honors - Minneapolis, MN 4 - NFL Super Bowl LII - Minneapolis, MN 5 - 7 - Country Radio Seminar - Nashville, TN 6 - 8 - Pollstar Live! – Los Angeles, CA 8 - Guild of Music Supervisors Awards - Los Angeles, CA 8 - 16 - New York Fashion Week (Fall/Winter 2018) - New York, NY 9 - 25 - 2018 Winter Olympics - Pyeongchang, South Korea 10 - The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ Sci-Tech Awards - Los Angeles, CA 11 - The Writers Guild Awards - Los Angeles, CA 13 - Mardi Gras 14 - Valentine's Day 14 - Barbershop Harmony Society’s “Singing Valentines” Day 14 - NME Awards - London, UK 14 - 18 - Folk Alliance Conference - Kansas City, MO 16 - Lunar New Year 18 - BAFTA Awards - London, UK 18 - NBA All-Star Game - Los Angeles, CA 18 - Daytona 500 - Daytona Beach, FL 19 - Presidents’ Day, SHORE FIRE MEDIA offices closed 19 - 25 - Noise Pop Festival - San Francisco, CA 21 - Academy of Country Music Awards second round ballot closes 21 - BRIT Awards - London, UK 22 - 24 - Durango Songwriters Expo - Ventura, CA 22 - 25 - Millennium Music Conference & Showcase - Harrisburg, PA 24 - 25 - Electric Daisy Carnival Mexico - Mexico City, Mexico 27 - The Oscars final ballot closes 27 - Laureus World Sports Awards - Monaco 28 - The Oscars Concert - Los Angeles, CA MARCH 2018 1 - 3 - by:Larm - Oslo, Norway 1 - 4 - Okeechobee Music & Arts Festival - Okeechobee, FL 2 - 4 - McDowell Mountain Music Festival- -

Mountain West Postpones All Fall Sports Indefinitely

TO PLAY, OR NOT Sports TO PLAY? LOCAL Get the latest as Zoo Boise to hold XTRA conferences debate Subscribers will find on whether to cancel annual ‘Zoobilee’ this bonus content at the upcoming college idahostatesman.com/ fundraiser online football season. eedition JOHN BAZEMORE AP because of virus 3A VOLUME 156, No. 17 FACEBOOK.COM/IDAHOSTATESMAN LOCAL NEWS ALL DAY. Sunny WWW.IDAHOSTATESMAN.COM TWITTER.COM/IDAHOSTATESMAN YOUR WAY. TUESDAY AUGUST 11 2020 $1.50 96°/62° See 7A tions, including playing next spring, according to Monday’s release. Mountain West postpones The Mountain West is the second FBS conference to cancel its fall season, following the Mid-American Conference. all fall sports indefinitely Old Dominion Uni- versity — a Conference USA school in Virginia — disease caused by the new football, which was to not dent-athletes, coaches every possible uncertain- and James Madison Uni- BY RON COUNTS coronavirus. allow games until the and staff had been prepar- ty, but in the end, the versity, one of the top FCS [email protected] “The MW Board of week of Sept. 26, already ing for a 2020 season,” physical and mental well- programs in the country, Directors prioritized the had cost Boise State its Boise State Athletic Direc- being of student-athletes both also opted to cancel The Boise State football mental health and well- opener against Georgia tor Curt Aspey said in a across the conference their seasons Monday. team won’t take the field being of the conference’s Southern, and the ACC’s statement released Mon- necessitated today’s an- Two FCS conferences for regular-season games student-athletes and over- restrictions on where day by the university. -

“Something About the Way You Look Tonight” Geneva Jackson Advised

“Something About the Way You Look Tonight” Popular Music Festivals as Rites of Passage in the Contemporary United States Geneva Jackson Advised by Judith Schachter Carnegie Mellon University Dietrich College Honors Fellowship Program Spring 2016 Acknowledgements This project was made possible by the love and support of many people, to whom I will be forever indebted. First, I would like to thank the Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences, for the creation of the Honors Fellowship Program, through which I received additional support to begin work on my thesis over the summer of 2015. I am thankful for the opportunity to explore my nonacademic interests in an academic setting. Weekly meetings with the other fellows, Eleanor Haglund, Kaylyn Kim, Kaytie Nielsen, Sayre Olson, Lucy Pei, Chloe Thompson, and Laurnie Wilson, as well as our mentors Dr. Joseph Devine, Dr. Jennifer Keating-Miller, and Dr. Brian Junker, were invaluable in the formation of my topic focus. Thank you for the laughter and advice. I’d also like to express endless gratitude to my thesis advisor, Dr. Judith Schachter, for her limitless encouragement, critical eye, and keen ability to parse out exactly I was trying to say when my phrasing became cumbersome. I would like also to acknowledge Dr. Scott Sandage for agreeing to consult with me over the summer and to thank him for telling the freshman-engineering-major version of me to consider a history degree. Special thanks must be given to my music festival partners, Catherine Kildunne, Emily Clark, Ian Einhorn, Sam Ho, and Anthony Comport, without whom field research would have been a woefully solitary task. -

Shore Fire Best Calendar 2019 DRAFT

SHORE FIRE MEDIA’S 2018/2019 BEST CALENDAR MARCH 2019 1 - 3 - McDowell Mountain Music Festival - Phoenix, AZ 2 - 3 - Innings Festival - Tempe, AZ 5 - Mardi Gras - New Orleans, LA 5 - ASCAP Latin Music Awards - San Juan, Puerto Rico 5 - 8 - International Live Music Conference - London, UK 8 - 17 - South By Southwest - Austin, TX 9 - 10 - Jazz in the Gardens Music Festival - Miami, FL 13 - The Library of Congress Gershwin Prize for Popular Song - Washington, DC 13 - 16 - SUNDARA - Riviera Maya, Mexico 14 - The Ellies, National Magazine Awards Gala- New York, NY 14 - iHeartRadio Music Awards - Los Angeles, CA 15 - 24 - PaleyFest LA - Los Angeles, CA 17 - Juno Awards - Vancouver, BC Canada 17 - St. Patrick’s Day 19 - Academy of Country Music Awards final round ballot closes 20 - 24 - Treefort Music Fest - Boise, ID 21 - Michael Dorf Presents' “The Music Of Van Morrison” tribute show - New York, NY 21 - 24 - Big Ears Festival - Knoxville, TN 22 - 23 - Salute the Troops Music and Comedy Festival - Riverside, CA 22 - 24 - Chicago Comic & Entertainment Expo - Chicago, IL 22 - 24 - LA Fashion Week - Los Angeles, CA 23 - Kids’ Choice Awards - Inglewood, CA 24 - 25 - In Bloom Music Festival - Houston, TX 24 - 27 - MUSEXPO Creative Summit - Burbank, CA 27 - 29 - Worldwide Radio Summit - Burbank, CA 28 - MLB Opening Day 28 - APR 13 - Savannah Music Festival - Savannah, GA 29 - Stellar Gospel Music Awards - Las Vegas, NV 29 - 31 - Ultra Music Festival - Miami, FL 29 - 31 - WonderCon - Anaheim, CA 29 - 31 - Lollapalooza Chile - Santiago, Chile 29 - -

Idaho Native Keith Allred Answers a Resounding "Yes" to That Question, and Now Has a National Platform to Try and Make That Happen

#2407 - 04/26/2019 Keith Allred Can we all just get along better? Idaho native Keith Allred answers a resounding "yes" to that question, and now has a national platform to try and make that happen. In this Dialogue episode, Allred, the new executive director of the National Institute for Civil Discourse (NICD), talks with host Marcia Franklin about his vision. Allred, the Democratic nominee for the Idaho governorship in 2010, is a mediator who founded The Common Interest, a multi-party citizens' group that studied Idaho legislative issues and came to a consensus on positions. He is taking that model to a national level with a new initiative at NICD called "CommonSense American." Although political rancor is high right now, Allred just sees that as an opportunity for positive change. "I have never been more optimistic than I am today," he tells Franklin. Mr. Allred graduated from Twin Falls High School, and received an undergraduate degree from Stanford University and a Ph.D. from UCLA. #2406 - 01/11/2019 Columnist Nicholas Kristof Host Marcia Franklin talks with Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof. Kristof was in Boise in October, 2018 to address the fall conference of the Idaho Women’s Charitable Foundation. The two discuss Kristof's views on current social issues in America. His next book will look at those concerns, focusing on his hometown of Yamhill, Oregon. Kristof talks about programs he believes would help ameliorate the problems, and they also discuss the role of private philanthropy. Franklin also asks Kristof about international topics, as he spends much of his time reporting from foreign countries, and he shares his thoughts on which of his stories he’s most proud. -

Home & Plants Issue

CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE | APRIL | APRIL CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE Home & Plants Issue How to make the most of your fl ora and furnishings THIS WEEK CHICAGOREADER | APRIL | VOLUME NUMBER IN THIS ISSUE TR - 08 NewsDoulasareworking concertsandotherupdated @ doubletimetoseeparents listings throughsafeempoweredbirthsin 31 GossipWolfHiphopactivist acrisis Jamie“JMilla”Sevierdiesat PTB ECS K KH andWellYellsdropsanew CLR H darkwavealbumthattraffi cksin MEP M thesonicsofisolation TDKR CEBW AEJL intothewackyo enoverlooked SWMD LG worldofrareandantiquebooks DI BJ MS EAS N L CITYLIFE Pornodespiteitsracytitleisalot GD AH 03 TransportationWouldanEast moreSavedmeetsDemonsthan L CSC-J BaystyleSlowStreetsprogrambe itisDeepThroatandDeerskinis CEBN B L C M DLCMC benefi cialinChicagoduringthe abizarrehorrorcomedyfeaturing J F S F JH I coronaviruscrisis? AdeleHaenel H C MJ HOME&PLANTS MKSK Chicagoans ND L JL 11 FavoriteThings MUSIC& MMAM -K sharetheobjectsthatmaketheir J R N JN M O homesgoodplacestobe NIGHTLIFE M S CS 14 ComicIndefenseofclutter 22 FeatureChicagoindierockers OPINION ---------------------------------------------------------------- 16 PropagationMoneydoesn’t Ratboysrecentlyreleasedtheir 32 SavageLoveDanSavageoff ers DD J D D DCW growontreesbutothertreesdo! bestalbumyetandthoughthey adviceforawomandrowningin SMCJ G can’ttourthey’refi ndingwaysto arousaleveninapandemic! MPC THEATER stayconnectedtotheirfans YD SSP 18 ImprovChicagoimprovand 26 InRotationCurrentmusical CLASSIFIEDS ATA comedyclassesfi llthequarantine obsessionsofHuntsmenbassist -

Boisetm Magazine &

lifestyle | shopping | entertainment | events | visitor information | relocation Welcome to BoiseTM magazine & INSIDE: BIKE FRIENDLY BOISE Pick up your complimentary copy at CONCIERGE CORNER & VISITOR SERVICES Located at the Southeast corner of Front Street and Ninth 2016 TREASURE VALLEY’S PREMIER SHOPPING, DINING, & ENTERTAINMENT DESTINATION SHOPPING ENTERTAINMENT DINING Anthropologie Village Cinema Kona Grill LUXURY THEATER with VIP SEATING lululemon Yard House Big Al’s LOFT Twig’s Bistro BOWLING ARCADE & SPORTS BAR Chico’s Casa Del Matador White House | Black Market Backstage Bistro and more Grimaldi’s Pizzeria /TheVillageAtMeridian TheVillageAtMeridian.com /VillageMeridian Located at Eagle Road and Fairview Avenue CAL15-0040_WTBA_ad_8-375x10-875_v2.indd 1 1/5/16 9:31 AM LETTER FROM THE EDITOR ...............................................................................4 FROM THE MAYOR ..................................................................................................5 City of Boise Mayor David H. Bieter welcomes you to Boise. BOISE CITY OF TREES 2016 ................................................................................6 The big city with a small town heart. A look at Boise’s past, present and at what the future may have to offer. FACTS AT A GLANCE ............................................................................................12 What’s so great about Boise? Get the facts about Boise’s geography, population, housing, cost of living and more. ATTRACTIONS ......................................................................................................... -

Recording Academy and Musicares Commit $2M for Coronavirus Relief

Bulletin YOUR DAILY ENTERTAINMENT NEWS UPDATE MARCH 17, 2020 Page 1 of 34 INSIDE Recording Academy and • From Drive- MusiCares Commit $2M In Concerts to Livestream Raves, For Coronavirus Relief Fund Artists Band Together to Keep BY TATIANA CIRISANO Music Alive Amid Coronavirus The coronavirus outbreak has left countless the ground, and people in the communities who know • With Coachella members of the music community in a financial exactly how to help, and what’s going to be a differ- & Coronavirus 1-2 bind, as each tour and festival cancellation means ence-maker for a lot of people,” he says. “Some people Punch, Indio’s Local Economy Faces Hard dozens of lost paychecks. That’s not to mention need help with their rent, some need to buy groceries, Road Ahead concern over the virus itself, which has begun to some need medical care. The infrastructure around afflict members of the industry. MusiCares is set up to deal with specifically that.” • Billboard Music In response, the Recording Academy and its chari- Similarly, three days after Hurricane Katrina rav- Awards Postponed table arm, MusiCares, are today (March 17) launching aged the gulf region in 2005, MusiCares and the acad- Due to Coronavirus a coronavirus relief fund for music professionals ad- emy dedicated $1 million to help victims of the storm. • Billboard Latin versely impacted by the virus, starting with an initial After a five-year effort, MusiCares ended up distribut- Music Awards $1 million donation from each. MusiCares is also in ing more than $4.5 million to more than 4,500 music Postponed Due to the process of securing donations from several major professionals — helping with everything from medical Coronavirus streaming services, record labels and other music expenses and relocation costs to instrument repair. -

Natural Natural | Official Idaho State Travel Guide Travel State Idaho Official |

SOUTHWEST IDAHO SOUTHWEST GIVE IN TO NATURALNATURAL ATTRACTIONS | OFFICIAL IDAHO STATE TRAVEL GUIDE TRAVEL | OFFICIAL STATE IDAHO 70 Lake Cascade Traveling in southwest Idaho is like packing lots of super-fun vacations into one. You can hike through evergreen forests to remote alpine lakes or spy ante- lope roaming the high-country desert—or in just minutes, move from bustling city life to farmlands and fruit orchards. It’s the kind of place where you start your morning with a pint of local berries from a downtown farmers market, hit the trails or the whitewater, and head back in plenty of time to grab a bite and watch a Shake- speare performance. Definitely seek out local Idaho food and wines—both are receiving the same high acclaim that the region’s recreational offerings have long enjoyed. In fact, southwest Idaho’s ideal grape-growing conditions have led to the designation of two American Viticultural Areas—so put a winery tour on your short list. Plan to spend time in Boise, Idaho’s capital city, for a lively arts and culture scene, river and foothills fun, and Boise State University games. Boise’s also a central hub for day trips to scenic spots like McCall, Cascade, and Idaho City to the north—and Silver City, sand dunes, and the world’s most dense concentration of nesting birds of prey just to the south. For more about southwest Idaho, go to visitidaho.org/southwest Follow Visit Idaho on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and other social media channels. visitidaho.org | 71 #VisitIdaho SOUTHWEST IDAHO SOUTHWEST ‹ COMPLIMENTARY GOOSEBUMPS INCLUDED Shore Lodge, McCall Rhodes Skate Park VALLEY & ADAMS COUNTY roll into the small town of Cambridge, the southern gateway to Hells Canyon, When one of the main roads through North America’s deepest river gorge. -

10 Misc. Page

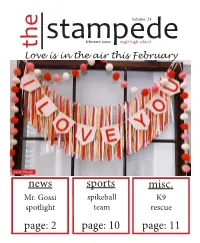

volume: 24 stampedefebruary issue eagle high school the Love is in the air this February Avery Woods news sports misc. Mr. Gossi spikeball K9 spotlight team rescue page: 2 page: 10 page: 11 2 News News Joe Gossi is a well-rounded teacher “During football season, you to actually learn something that can see me at every home BSU they will use in real life.” football game,” said Gossi. “I Because Gossi is so involved Briefs have season tickets.” with the activities and clubs of ACADECA- They are Gossi is head of BPA and a Eagle High, he is a ‘hit’ around competing at the ACADECA new club, Spike Ball club. BPA the school. The kids in his state competition on March 15 educates kids on many things classes, clubs and on his team and March 16 at Boise State. in the professional aspect of the love being around “Da Goss They hope to do even better at world. It focuses on leadership, Boss.” state in March. academic and technological “He is just so fun to be around,” ASL Club- Centennial, Eagle skills in the workplace. said junior Mason Leavitt. “At and Rocky Mountain High ASL “BPA is about being able to baseball practices he sometimes clubs are inviting everyone to communicate with people, doing can’t stop talking and it’s really a West Ada event to have fun community service learning, funny.” and raise money for the deaf being a professional and figuring Leavitt has been on varsity community. The event will take out what that means,” Gossi baseball since his freshman year place on March 1 from 5:30-7:30 Joe Gossi teaches in his natural habitat. -

Welcometo Boisetm

lifestyle | shopping | entertainment | events | visitor information | relocation 2017 TM Welcome to Boise magazine Inside: The secret is out! Boise IS one of the best places to live in the U.S.! Pick up your complimentary copy at CONCIERGE CORNER & VISITOR SERVICES Located at the Southeast corner of Front Street and Ninth LYSI BISHOP REAL ESTATE KELLER WILLIAMS REALTY BOISE Get in today… …and out to play. Same-day appointments The best kind of healthcare is close to home, and available when you Extended clinic hours need it. So you and your family can stay healthy, or recover quickly. Convenient locations That’s why Saint Alphonsus is all about making care convenient, with more clinic locations, longer hours, and more options for quick care. Walk-in urgent care clinics open seven days a week You can walk in to any one of our urgent care clinics, or visit with a MyeVisit online urgent care provider online from the comfort of home. No appointment needed. 24/7 emergency care At Saint Alphonsus, we’re here when you need us. So you can get 60+ clinics throughout back to doing what you love…with the people you love. Because the Treasure Valley best kind of healthcare is all about you. FIND A DOCTOR SaintAlphonsus.org 367-DOCS LETTER FROM THE SPONSOR ........................ 3 EDITOR Jeanne Huff LETTER FROM THE EDITOR ........................... 4 [email protected] LETTER FROM THE MAYOR . 5 BOISE CITY OF TREES ............................... 6 ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER Boise, past and present. Cindy Suffa FACTS AT A GLANCE ............................... 12 [email protected] Up-to-date statistics re: Boise’s geography, population, housing, cost of living and more.