“Something About the Way You Look Tonight” Geneva Jackson Advised

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

J. Dennis Thomas. Concert and Live Music Photography. Pro Tips From

CONCERT AND LIVE MUSIC PHOTOGRAPHY Pro Tips from the Pit J. DENNIS THOMAS Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier 225 Wyman Street, Waltham, MA 02451, USA The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, Oxford, OX5 1GB, UK © 2012 Elsevier Inc. Images copyright J. Dennis Thomas. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangements with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions. This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein). Notices Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary. Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility. To the fullest extent of the law, neither the Publisher nor the authors, contributors, or editors, assume any liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions, or ideas contained in the material herein. -

Prbis Brainscan

VOLUME 1 ISSUE 3 MAY/JUNE 2011 PRBIS BRAINSCAN LIFE BEYOND ACQUIRED BRAIN INJURY POWELL RIVER BRAIN INJURY SOCIETY Brain Injury 101 – a Marathon for Awareness Date: Saturday June 11, 2011 Location: Pacific Coastal Highway Our new marathon goal - the Pacific Coastal Highway, which includes Highway 101 Brain Injury 101 – a Marathon for Aware- ness For the purpose of: •promoting public awareness of Acquired Brain Injury •raising money to allow us to continue helping our clients and their caregivers. PRBIS BRAINSCAN Page 2 Walk For Awareness of Acquired Brain Injury In 2009 we walked the length of our section of Highway 101. This part of the Pacific Coastal Highway is 56 kilometers in length, start- ing in Lund, passing through Powell River and ending in Saltery Bay, where the ferry connects to the next part of Highway 101. This first walk was completed over 3 days. Participants were clients, professionals and ordinary citizens who wanted to take part in this public awareness project. Money was raised with pledges of sup- port to the walkers as well as business sponsors for each kilometer. For the second year, we offered more options on distance to com- plete – 1, 2, 5 or 10 kilometers, or for the truly fit, the entire 56 kilo- meters. Those who participated did so by walking, running or bicy- cling. We invited not only clients, family and ordinary citizens, but also contacted athletes, young athletes and sports associations to join our cause and complete the 56 kilometers ultra-marathon. _______________________________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________________________ VOLUME 1 ISSUE 3 Page 3 PRBIS BRAINSCAN Page 4 The Too Much Sugar Easter Celebration Linda Boutilier, our resident chocolatier and cake decorator, once again graced our lovely little office with yummy goodness. -

Public Health Management at Outdoor Music Festivals"

PUBLIC HEALTH MANAGEMENT AT OUTDOOR MUSIC FESTIVALS CAMERON EARL Ass Dip Health Surveying; Masters in Community and Environmental Health Graduate Certificate in Health Science Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Health Science, School of Public Health Faculty of Health Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane January 2006 2 Thesis Abstract Background Information: Outdoor music festivals (OMFs) are complex events to organise with many exceeding the population of a small city. Minimising public health impacts at these events is important with improved event planning and management seen as the best method to achieve this. Key players in improving public health outcomes include the environmental health practitioners (EHPs) working within local government authorities (LGAs) that regulate OMFs and volunteer organisations with an investment in volunteer staff working at events. In order to have a positive impact there is a need for more evidence and to date there has been limited research undertaken in this area. The research aim: The aim of this research program was to enhance event planning and management at OMFs and add to the body of knowledge on volunteers, crowd safety and quality event planning for OMFs. This aim was formulated by the following objectives. 1. To investigate the capacity of volunteers working at OMFs to successfully contribute to public health and emergency management; 2. To identify the key factors that can be used to improve public health management at OMFs; and 3. To identify priority concerns and influential factors that are most likely to have an impact on crowd behaviour and safety for patrons attending OMFs. -

University of Southern Queensland Behavioural Risk At

University of Southern Queensland Behavioural risk at outdoor music festivals Aldo Salvatore Raineri Doctoral Thesis Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Professional Studies at the University of Southern Queensland Volume I April 2015 Supervisor: Prof Glen Postle ii Certification of Dissertation I certify that the ideas, experimental work, results, analyses and conclusions reported in this dissertation are entirely my own effort, except where otherwise acknowledged. I also certify that the work is original and has not been previously submitted for any other award, except where otherwise acknowledged. …………………………………………………. ………………….. Signature of candidate Date Endorsement ………………………………………………….. …………………… Signature of Supervisor Date iii Acknowledgements “One’s destination is never a place, but a new way of seeing things.” Henry Miller (1891 – 1980) An outcome such as this dissertation is never the sole result of individual endeavour, but is rather accomplished through the cumulative influences of many experiences and colleagues, acquaintances and individuals who pass through our lives. While these are too numerous to list (or even remember for that matter) in this instance, I would nonetheless like to acknowledge and thank everyone who has traversed my life path over the years, for without them I would not be who I am today. There are, however, a number of people who deserve singling out for special mention. Firstly I would like to thank Dr Malcolm Cathcart. It was Malcolm who suggested I embark on doctoral study and introduced me to the Professional Studies Program at the University of Southern Queensland. It was also Malcolm’s encouragement that “sold” me on my ability to undertake doctoral work. -

The Politics of Urban Cultural Policy Global

THE POLITICS OF URBAN CULTURAL POLICY GLOBAL PERSPECTIVES Carl Grodach and Daniel Silver 2012 CONTENTS List of Figures and Tables iv Contributors v Acknowledgements viii INTRODUCTION Urbanizing Cultural Policy 1 Carl Grodach and Daniel Silver Part I URBAN CULTURAL POLICY AS AN OBJECT OF GOVERNANCE 20 1. A Different Class: Politics and Culture in London 21 Kate Oakley 2. Chicago from the Political Machine to the Entertainment Machine 42 Terry Nichols Clark and Daniel Silver 3. Brecht in Bogotá: How Cultural Policy Transformed a Clientist Political Culture 66 Eleonora Pasotti 4. Notes of Discord: Urban Cultural Policy in the Confrontational City 86 Arie Romein and Jan Jacob Trip 5. Cultural Policy and the State of Urban Development in the Capital of South Korea 111 Jong Youl Lee and Chad Anderson Part II REWRITING THE CREATIVE CITY SCRIPT 130 6. Creativity and Urban Regeneration: The Role of La Tohu and the Cirque du Soleil in the Saint-Michel Neighborhood in Montreal 131 Deborah Leslie and Norma Rantisi 7. City Image and the Politics of Music Policy in the “Live Music Capital of the World” 156 Carl Grodach ii 8. “To Have and to Need”: Reorganizing Cultural Policy as Panacea for 176 Berlin’s Urban and Economic Woes Doreen Jakob 9. Urban Cultural Policy, City Size, and Proximity 195 Chris Gibson and Gordon Waitt Part III THE IMPLICATIONS OF URBAN CULTURAL POLICY AGENDAS FOR CREATIVE PRODUCTION 221 10. The New Cultural Economy and its Discontents: Governance Innovation and Policy Disjuncture in Vancouver 222 Tom Hutton and Catherine Murray 11. Creating Urban Spaces for Culture, Heritage, and the Arts in Singapore: Balancing Policy-Led Development and Organic Growth 245 Lily Kong 12. -

Sf Best Cal Fall 2019

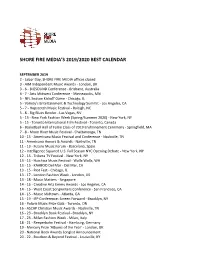

SHORE FIRE MEDIA’S 2019/2020 BEST CALENDAR SEPTEMBER 2019 2 - Labor Day, SHORE FIRE MEDIA offices closed 3 - AIM Independent Music Awards - London, UK 3 - 6 - BIGSOUND Conference - Brisbane, Australia 4 - 7 - Arts Midwest Conference - Minneapolis, MN 5 - NFL Season Kickoff Game - Chicago, IL 5 - Variety’s EntertainMent & Technology SumMit - Los Angeles, CA 5 - 7 - Hopscotch Music Festival - Raleigh, NC 5 - 8 - Big Blues Bender - Las Vegas, NV 5 - 13 - New York Fashion Week (Spring/Summer 2020) - New York, NY 5 - 15 - Toronto International Film Festival - Toronto, Canada 6 - Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2019 EnshrineMent Ceremony - Springfield, MA 7 - 8 - Moon River Music Festival - Chattanooga, TN 10 - 15 - AMericana Music Festival and Conference - Nashville, TN 11 - AMericana Honors & Awards - Nashville, TN 11 - 13 - Future Music Forum - Barcelona, Spain 12 - Intelligence Squared U.S. Fall Season NYC Opening Debate - New York, NY 12 - 15 - Tribeca TV Festival - New York, NY 13 - 14 - Huichica Music Festival - Walla Walla, WA 13 - 15 - KAABOO Del Mar - Del Mar, CA 13 - 15 - Riot Fest - Chicago, IL 13 - 17 - London Fashion Week - London, UK 13 - 18 - Music Matters - Singapore 14 - 15 - Creative Arts EmMy Awards - Los Angeles, CA 14 - 15 - West Coast Songwriters Conference - San Francisco, CA 14 - 15 - Music Midtown - Atlanta, GA 15 - 19 - IFP Conference: Screen Forward - Brooklyn, NY 16 - Polaris Music Prize Gala - Toronto, ON 16 - ASCAP Christian Music Awards - Nashville, TN 16 - 23 - Brooklyn Book Festival - Brooklyn, NY 17 - 23 -

Punk Rock and the Socio-Politics of Place Dissertation Presented

Building a Better Tomorrow: Punk Rock and the Socio-Politics of Place Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Jeffrey Samuel Debies-Carl Graduate Program in Sociology The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Townsand Price-Spratlen, Advisor J. Craig Jenkins Amy Shuman Jared Gardner Copyright by Jeffrey S. Debies-Carl 2009 Abstract Every social group must establish a unique place or set of places with which to facilitate and perpetuate its way of life and social organization. However, not all groups have an equal ability to do so. Rather, much of the physical environment is designed to facilitate the needs of the economy—the needs of exchange and capital accumulation— and is not as well suited to meet the needs of people who must live in it, nor for those whose needs are otherwise at odds with this dominant spatial order. Using punk subculture as a case study, this dissertation investigates how an unconventional and marginalized group strives to manage ‘place’ in order to maintain its survival and to facilitate its way of life despite being positioned in a relatively incompatible social and physical environment. To understand the importance of ‘place’—a physical location that is also attributed with meaning—the dissertation first explores the characteristics and concerns of punk subculture. Contrary to much previous research that focuses on music, style, and self-indulgence, what emerged from the data was that punk is most adequately described in terms of a general set of concerns and collective interests: individualism, community, egalitarianism, antiauthoritarianism, and a do-it-yourself ethic. -

Safe and Healthy Mass Gatherings AUSTRALIAN DISASTER RESILIENCE HANDBOOK COLLECTION Safe and Healthy Mass Gatherings Manual 12

Australian Disaster Resilience Handbook Collection MANUAL 12 Safe and Healthy Mass Gatherings AUSTRALIAN DISASTER RESILIENCE HANDBOOK COLLECTION Safe and Healthy Mass Gatherings Manual 12 Attorney-General’s Department Emergency Management Australia © Commonwealth of Australia 1999 Attribution Edited and published by the Australian Institute Where material from this publication is used for any for Disaster Resilience, on behalf of the Australian purpose, it is to be attributed as follows: Government Attorney-General’s Department. Edited, typeset and published by Emergency Source: Australian Disaster Resilience Manual 12: Safe Management Australia and Healthy Mass Gatherings, 1999, Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience CC BY-NC Printed in Australia by Better Printing Service Using the Commonwealth Coat of Arms Copyright The terms of use for the Coat of Arms are available from The Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience the It’s an Honour website (http://www.dpmc.gov.au/ encourages the dissemination and exchange of government/its-honour). information provided in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia owns the copyright in all Contact material contained in this publication unless otherwise noted. Enquiries regarding the content, licence and any use of this document are welcome at: Where this publication includes material whose copyright The Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience is owned by third parties, the Australian Institute for 370 Albert St Disaster Resilience has made all reasonable efforts to: East Melbourne Vic 3002 • clearly label material where the copyright is owned by Telephone +61 (0) 3 9419 2388 a third party www.aidr.org.au • ensure that the copyright owner has consented to this material being presented in this publication. -

Shore Fire Best Calendar 2018

SHORE FIRE MEDIA’S 2018 BEST CALENDAR FEBRUARY 2018 1 - Super Bowl Gospel Celebration - St. Paul, MN 3 - Directors Guild Awards - Los Angeles, CA 3 - NFL Honors - Minneapolis, MN 4 - NFL Super Bowl LII - Minneapolis, MN 5 - 7 - Country Radio Seminar - Nashville, TN 6 - 8 - Pollstar Live! – Los Angeles, CA 8 - Guild of Music Supervisors Awards - Los Angeles, CA 8 - 16 - New York Fashion Week (Fall/Winter 2018) - New York, NY 9 - 25 - 2018 Winter Olympics - Pyeongchang, South Korea 10 - The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ Sci-Tech Awards - Los Angeles, CA 11 - The Writers Guild Awards - Los Angeles, CA 13 - Mardi Gras 14 - Valentine's Day 14 - Barbershop Harmony Society’s “Singing Valentines” Day 14 - NME Awards - London, UK 14 - 18 - Folk Alliance Conference - Kansas City, MO 16 - Lunar New Year 18 - BAFTA Awards - London, UK 18 - NBA All-Star Game - Los Angeles, CA 18 - Daytona 500 - Daytona Beach, FL 19 - Presidents’ Day, SHORE FIRE MEDIA offices closed 19 - 25 - Noise Pop Festival - San Francisco, CA 21 - Academy of Country Music Awards second round ballot closes 21 - BRIT Awards - London, UK 22 - 24 - Durango Songwriters Expo - Ventura, CA 22 - 25 - Millennium Music Conference & Showcase - Harrisburg, PA 24 - 25 - Electric Daisy Carnival Mexico - Mexico City, Mexico 27 - The Oscars final ballot closes 27 - Laureus World Sports Awards - Monaco 28 - The Oscars Concert - Los Angeles, CA MARCH 2018 1 - 3 - by:Larm - Oslo, Norway 1 - 4 - Okeechobee Music & Arts Festival - Okeechobee, FL 2 - 4 - McDowell Mountain Music Festival- -

Journal of the Music & Entertainment Industry Educators

Journal of the Music & Entertainment Industry Educators Association Volume 20, Number 1 (2020) Bruce Ronkin, Editor Northeastern University Paul Linden, Associate Editor University of Southern Mississippi Ben O’Hara, Associate Editor (Book Reviews) Australian College of the Arts Published with Support from Amplifying Music: A Gathering of Perspectives on the Resilience of Live Music in Communities During the Early Stages of the COVID-19 Era Storm Gloor University of Colorado Denver https://doi.org/10.25101/20.1 Abstract As the novel coronavirus known as COVID-19 spread throughout the United States in March of 2020, the live music industry was shaken by temporary closures of venues, cancellation of festivals, and postpone- ments of tours, among other effects. However long and to what extent the damage to the music industry would be, one thing was certain. At some point there would need to be a return to (a possible “new”) normal. The Amplify Music virtual conference was one of the first gatherings of mu- sic industry stakeholders to immediately address issues around the indus- try’s resilience in this pandemic and what it might look like. Leaders from throughout the world participated in the twenty-five consecutive hour con- vening. This paper summarizes many of the perspectives, observations, and ideas presented in regard to the future of the United States music in- dustry post-pandemic. Keywords: coronavirus, COVID-19, Amplify Music, National Inde- pendent Venue Association, NIVA, livestreaming, resilience Introduction On the afternoon of March 2, 2020, Kate Becker, Creative Economy Strategist for King County, Washington, concluded her presentation at the closing session of a conference presented by the Responsible Hos- pitality Institute (RHI), an organization focused on nightlife in cities and “helping cities worldwide harness the power of the social economy.”1 The conference, held in the heart of downtown Seattle and mere blocks away from Ms. -

SPRING 2015 NUMBER 1 Page Ii 03-24.Docx (Do Not Delete) 3/24/2015 5:57 PM

SJA 2-1 toc 03-24.docx (Do Not Delete) 3/24/2015 5:47 PM THE LEGAL APPRENTICE FOREWORD ....................................................................................... v Dean Jeffrey P. Grossmann WELCOME NOTE ............................................................................ vii Honorable John F. Blawie ARTICLES WHAT HAPPENED TO THE 9/11 CROSS ............................................. 1 Andres Santamaria DIAMONDS ARE A GIRL’S BEST FRIEND ........................................... 7 Gabriella Labita HAIR TODAY, GONE FROM THE TEAM ........................................... 13 Brian Stevens STAGE DIVING ............................................................................... 19 Jenane Jeanty LAW STUDENTS AND UNDERGRADUATES LEARNING TOGETHER AT THE SECURITIES ARBITRATION CLINIC ............................. 23 Professor Christine Lazaro VOLUME 2 SPRING 2015 NUMBER 1 Page ii 03-24.docx (Do Not Delete) 3/24/2015 5:57 PM ST. JOHN’S UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF PROFESSIONAL STUDIES OFFICES OF ADMINISTRATION AND FACULTY 2014 – 2015 JEFFREY GROSSMANN, J.D. DEAN ELLEN TUFANO, PH.D. ASSOCIATE DEAN * * * ANTOINETTE COLLARINI-SCHLOSSBERG, J.D. CHAIRPERSON CRIMINAL JUSTICE, LEGAL STUDIES, HOMELAND SECURITY BERNARD HELLDORFER, J.D. DIRECTOR LEGAL STUDIES MARY NOE, J.D. ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR EDITOR JAMES CROFT, J.D. ASSISTANT PROFESSOR ASSISTANT EDITOR pg iii-iv.docx (Do Not Delete) 3/13/2015 12:19 PM THE LEGAL APPRENTICE FACULTY ADVISORY BOARD JAMES CROFT, ASSISTANT PROFESSOR B.A., J. D. ALBANY UNIVERSITY; ST. JOHN’S UNIVERSITY, SCHOOL -

The 2019-20 Grand Jury Report

FINAL CONSOLIDATED REPORT A Report for the Citizens of Yolo County, California Arcade Arroz Beatrice Brooks Browns Corner Cadenasso Capay Central 2019-20 Yolo County Citrona Kiesel Clarksburg Kings Farms Conaway Knights Landing Grand Jury Coniston Lovdal Daisie Lund Davis Madison Tancred Dufour Merritt Tyndall Landing Dunnigan Monument Hills University of California Davis El Macero Norton Valdez El Rio Villa Peethill Vin Esparto Plainfield Webster Fremont Riverview West Sacramento Green Rumsey Willow Point Greendale Saxon Winters Guinda Sorroca Woodland September 24, 2020 Hershey Sugarfield Yolo Jacobs Corner Swingle Zamora Woodland, California 2019-2020 YOLO COUNTY GRAND JURY FINAL CONSOLIDATED REPORT A Report for the Citizens of Yolo County, California September 24, 2020 Woodland, California i Acknowledgements Special thanks to jurors Lisa DeSanti, Ann Kokalis, Richard Kruger, Sherwin Lee, Lynn Otani, and Laurel Sousa for their extra time and effort in performing important officer duties during our term. Thanks also to all the jurors during our tenure who gathered information, contributed to the writing of the various individual committee reports, and worked the many hours required for thorough investigations. Cover Art by Judy Wohlfrom, 2017-2018 Foreperson ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................... ii Honorable Sonia Cortés .................................................................................... vi The 2019-2020 Yolo County Grand Jury