The Plumed Serpant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ÉÈ—¤Æ†²Ä¸€ Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

é 藤憲一 电影 串行 (大全) Visitor Q https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/visitor-q-2031745/actors Flower and Snake https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/flower-and-snake-16957593/actors Mari's Prey https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/mari%27s-prey-6760871/actors Family https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/family-3066229/actors The Guys from Paradise https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-guys-from-paradise-1536287/actors Deadly Outlaw: Rekka https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/deadly-outlaw%3A-rekka-913817/actors Cromartie High – The https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/cromartie-high-%E2%80%93-the-movie-3025926/actors Movie SS https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/ss-7393102/actors Agitator https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/agitator-2421466/actors The Man in White https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-man-in-white-3521742/actors Kikoku https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/kikoku-3571374/actors KÅs hÅn in https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/k%C5%8Dsh%C5%8Dnin-937293/actors 西鄉殿 https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/%E8%A5%BF%E9%84%89%E6%AE%BF-28359588/actors 20世紀少年 https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/20%E4%B8%96%E7%B4%80%E5%B0%91%E5%B9%B4-91458/actors 人ä¸ä ¹‹é¾ åŠ‡å ´ç‰ˆ https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/%E4%BA%BA%E4%B8%AD%E4%B9%8B%E9%BE%8D-%E5%8A%87%E5%A0%B4%E7%89%88-562135/actors 幫è€ç ˆ¸æ‹å ¼µç…§ https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/%E5%B9%AB%E8%80%81%E7%88%B8%E6%8B%8D%E5%BC%B5%E7%85%A7-11317940/actors 大å¸ä -

The Molecular Sciences Software Institute

The Molecular Sciences Software Institute T. Daniel Crawford, Cecilia Clementi, Robert Harrison, Teresa Head-Gordon, Shantenu Jha*, Anna Krylov, Vijay Pande, and Theresa Windus http://molssi.org S2I2 HEP/CS Workshop at NCSA/UIUC 07 Dec, 2016 1 Outline • Space and Scope of Computational Molecular Sciences. • “State of the art and practice” • Intellectual drivers • Conceptualization Phase: Identifying the community and needs • Bio-molecular Simulations (BMS) Conceptualization • Quantum Mechanics/Chemistry (QM) Conceptualization • Execution Phase. • Structure and Governance Model • Resource Distribution • Work Plan 2 The Molecular Sciences Software Institute (MolSSI) • New project (as of August 1st, 2016) funded by the National Science Foundation. • Collaborative effort by Virginia Tech, Rice U., Stony Brook U., U.C. Berkeley, Stanford U., Rutgers U., U. Southern California, and Iowa State U. • Total budget of $19.42M for five years, potentially renewable to ten years. • Joint support from numerous NSF divisions: Advanced Cyberinfrastructure (ACI), Chemistry (CHE), Division of Materials Research (DMR), Office of Multidisciplinary Activities (OMA) • Designed to serve and enhance the software development efforts of the broad field of computational molecular science. 3 Computational Molecular Sciences (CMS) • The history of CMS – the sub-fields of quantum chemistry, computational materials science, and biomolecular simulation – reaches back decades to the genesis of computational science. • CMS is now a “full partner with experiment”. • For an impressive array of chemical, biochemical, and materials challenges, our community has developed simulations and models that directly impact: • Development of new chiral drugs; • Elucidation of the functionalities of biological macromolecules; • Development of more advanced materials for solar-energy storage, technology for CO2 sequestration, etc. -

Library Book Resource Guide Resource Library Book

Library Book Resource Guide Library Book Resource Library Book List Reading Word Reading Reading Word Reading Series Book Classification Lexile* Series Book Classification Lexile* Age Count Level* Age Count Level* Go Facts Autumn NF 6 250 14 620 Go Facts Bread NF 7 300 15 700 Go Facts Cold NF 6 280 15 640 Go Facts Clean Water NF 7 300 16 610 Go Facts Doctor and Dentist NF 6 225 10 510 Go Facts Fuel NF 7 350 17 630 Go Facts Dry NF 6 250 14 660 Go Facts On The Road NF 7 300 15 740 Go Facts Find Your way NF 6 235 Go Facts Planes NF 7 350 17 710 Go Facts Hot NF 6 240 14 700 Go Facts Trains NF 7 300 16 680 Go Facts How Do Birds Fly? NF 6 300 12 570 Go Facts TV Show NF 7 350 17 660 Go Facts Life in Space NF 6 255 10 450 Storylands Clothes and Costumes NF 7 500 10 220 Go Facts Lift Off! NF 6 215 11 440 Storylands Famous Castles NF 7 500 18 850 Go Facts Lions and Tigers NF 6 240 11 570 Storylands Knights and Castles NF 7 500 9 260 Go Facts Natural Wonders NF 6 2000 940 Storylands Behind the Scenes NF 7 100 9 270L Go Facts Penguin Rescue NF 6 255 Storylands Boats and Ships NF 7 500 8 270 Go Facts People Who Help Us NF 6 310 12 490 Storylands Circuses Today NF 7 500 19 890L Go Facts Polar Bears NF 6 255 10 430 Storylands Coming to Land NF 7 500 9 350 Go Facts Spring NF 6 280 15 610 Storylands Dinosaurs NF 7 500 19 540 Go Facts Summer NF 6 230 14 560 Storylands Forest Minibeasts NF 7 500 10 420L Go Facts The Planets NF 6 220 11 410 Storylands Forests NF 7 500 8 Go Facts The Sun’s Energy NF 6 251 12 430 Storylands How to Circus NF 7 90 7 520 Go Facts -

Music 1000 Songs, 2.8 Days, 5.90 GB

Music 1000 songs, 2.8 days, 5.90 GB Name Time Album Artist Drift And Die 4:25 Alternative Times Vol 25 Puddle Of Mudd Weapon Of Choice 2:49 Alternative Times Vol 82 Black Rebel Motorcycle Club You'll Be Under My Wheels 3:52 Always Outnumbered, Never Outg… The Prodigy 08. Green Day - Boulevard Of Bro… 4:20 American Idiot Green Day Courage 3:30 ANThology Alien Ant Farm Movies 3:15 ANThology Alien Ant Farm Flesh And Bone 4:28 ANThology Alien Ant Farm Whisper 3:25 ANThology Alien Ant Farm Summer 4:15 ANThology Alien Ant Farm Sticks And Stones 3:16 ANThology Alien Ant Farm Attitude 4:54 ANThology Alien Ant Farm Stranded 3:57 ANThology Alien Ant Farm Wish 3:21 ANThology Alien Ant Farm Calico 4:10 ANThology Alien Ant Farm Death Day 4:33 ANThology Alien Ant Farm Smooth Criminal 3:29 ANThology Alien Ant Farm Universe 9:07 ANThology Alien Ant Farm The Weapon They Fear 4:38 Antigone Heaven Shall Burn To Harvest The Storm 4:45 Antigone Heaven Shall Burn Tree Of Freedom 4:49 Antigone Heaven Shall Burn Voice Of The Voiceless 4:53 Antigone (Slipcase - Edition) Heaven Shall Burn Rain 4:11 Ascendancy Trivium laid to rest 3:49 ashes of the wake lamb of god Now You've Got Something to Die … 3:39 Ashes Of The Wake Lamb Of God Relax Your Mind 4:07 Bad Boys 2 Soundtrack Loon Intro 0:12 Bad Boys 2 Soundtrack Bad Boys 2 Soundtrack Show Me Your Soul 5:20 Bad Boys 2 Soundtrack Loon Feat. -

BHM 1998 Feb.Pdf

TTABLEABLE OFOF CONTENTSCONTENTS MAGAZINE COMMITTEE A Message From the President.......................................................... 1 Features OFFICER IN CHARGE The Show’s New Footprint ........................................................ 2 J. Grover Kelley CHAIRMAN Blue Ribbon Judges ..................................................................... 4 Bill Booher Impact of Pay-Per-View — Now and in the Future ................... 6 VICE CHAIRMAN Taking Stock of Our Proud Past ............................................... 8 Bill Bludworth EDITORIAL BOARD 1998 Attractions & Events.......................................................... 10 Suzanne Epps C.F. Kendall Drum Runners.............................................................................. 12 Teresa Lippert Volunteer the RITE Way............................................................... 14 Peter A. Ruman Marshall R. Smith III Meet Scholar #1.................................................................... 15 Constance White Committee Spotlights COPY EDITOR Larry Levy International .................................................................................. 16 REPORTERS School Art ...................................................................................... 17 Nancy Burch Gina Covell World’s Championship Bar-B-Que ....................................... 18 John Crapitto Sue Cruver Show News and Updates Syndy Arnold Davis PowerVision Steps Proudly Toward the Future.......................... 19 Cheryl Dorsett Freeman Gregory Third-Year -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

The Ursinus Weekly, December 10, 1956

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College Ursinus Weekly Newspaper Newspapers 12-10-1956 The rsinU us Weekly, December 10, 1956 Lawrence C. Foard Ursinus College Ismar Schorsch Ursinus College Arthur King Ursinus College Thomas M. McCabe Ursinus College Ann Leger Ursinus College See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/weekly Part of the Cultural History Commons, Higher Education Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits oy u. Recommended Citation Foard, Lawrence C.; Schorsch, Ismar; King, Arthur; McCabe, Thomas M.; Leger, Ann; MacGregor, Bruce; Blood, Richard; and Rybak, Warren, "The rU sinus Weekly, December 10, 1956" (1956). Ursinus Weekly Newspaper. 418. https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/weekly/418 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ursinus Weekly Newspaper by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Lawrence C. Foard, Ismar Schorsch, Arthur King, Thomas M. McCabe, Ann Leger, Bruce MacGregor, Richard Blood, and Warren Rybak This book is available at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/weekly/418 LATE RELEASE: CHRISTMAS BANQUET J "WHO'S WHO" AND BALL WEDNESDAY EVENING reId!, SEE PAGE 4 Price, Ten Cents ~_I._5_~_N_O._8 ________________________- __MONDA~ DECE~ER 10, 1956 Christmas Parties "Morning Wateh"" Nineteenth Annual "Messiah" "y"" Groups Hear IAnnual Christmas For Children Given To Be Held by SWC Two SpeakersWed. -

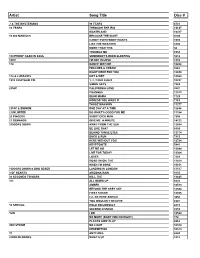

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

A Command-Line Interface for Analysis of Molecular Dynamics Simulations

taurenmd: A command-line interface for analysis of Molecular Dynamics simulations. João M.C. Teixeira1, 2 1 Previous, Biomolecular NMR Laboratory, Organic Chemistry Section, Inorganic and Organic Chemistry Department, University of Barcelona, Baldiri Reixac 10-12, Barcelona 08028, Spain 2 DOI: 10.21105/joss.02175 Current, Program in Molecular Medicine, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario M5G 0A4, Software Canada • Review Summary • Repository • Archive Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of biological molecules have evolved drastically since its application was first demonstrated four decades ago (McCammon, Gelin, & Karplus, 1977) and, nowadays, simulation of systems comprising millions of atoms is possible due to the latest Editor: Richard Gowers advances in computation and data storage capacity – and the scientific community’s interest Reviewers: is growing (Hospital, Battistini, Soliva, Gelpí, & Orozco, 2019). Academic groups develop most of the MD methods and software for MD data handling and analysis. The MD analysis • @amritagos libraries developed solely for the latter scope nicely address the needs of manipulating raw data • @luthaf and calculating structural parameters, such as: MDAnalysis (Gowers et al., 2016; Michaud- Agrawal, Denning, Woolf, & Beckstein, 2011); (McGibbon et al., 2015); (Romo, Submitted: 03 March 2020 MDTraj LOOS Published: 02 June 2020 Leioatts, & Grossfield, 2014); and PyTraj (Hai Nguyen, 2016; Roe & Cheatham, 2013), each with its advantages and drawbacks inherent to their implementation strategies. This diversity License enriches the field with a panoply of strategies that the community can utilize. Authors of papers retain copyright and release the work The MD analysis software libraries widely distributed and adopted by the community share under a Creative Commons two main characteristics: 1) they are written in pure Python (Rossum, 1995), or provide a Attribution 4.0 International Python interface; and 2) they are libraries: highly versatile and powerful pieces of software that, License (CC BY 4.0). -

'-L? Ч ¿X^Ic.*Isi Iéí.55.3?£ If:.Y •5:И';:Гй^*'1Г І I ,/R Ί^··^^·;:*^Ϊ··':·'·':>7

S'-Ё’ psijL áí. pj: SÎÆ, :? i'“: ï ïf* гГтл c'rL '^ · ’’V^ í‘j ’**·* :?S. »>и·. i*». «- * Ь y I m ·^ · ^i:¡y?'íT*ü i^Ä W-Ä .,;í¿· ■» ·,· fiS}*«,' -jii Ц İ>4ÇJ ..j«. "'* ;»!·Γ“ Ц ^ «*»?*;·»/ ц‘•■W st-tïw . f'Tf'Y Λ а d ^ ÎL ^tewolM vs î! S >^*;·IfİflMpriilbt“ 4sj:'· C t : äi« 5 ¿Й ii ' . ¿ İ l ç j Y І^Ш ТУ;гГ .■"■ ! ■ !5 .’! t - =< ■ -t«, ,., ψ : r, ■ Jü'S s; - ÿ : : . іЗ^ CS 'mİ ir¿;ííí é « :і.мгж? ■i::'^r.r‘;íK f. · ’ '?’’.‘f ’V '"'^^'Γ:!·’!·^ ·~ І;4^-й.:ГѵГ:5;с J^1й:5.;*ií·:|'·^* lч d .v W *· , ‘-? ■ ¿X^ic.*iSi iéí.55.3?£ í s í * ’· ·■ ^ ■ ЛМт.^'' é·**»!·4(¡ff· „.--.·;·^« .JJ, g. ψ·’;· ^ if:.Y ■•5:И';:Гй^*‘1г І I W 'ill · äi-3':» і»£'лгіт;ьѵй-г·) ·«»■. ·α..ί í¡ %' Ím^í », i.]«·« îi» ' ,/r ί^··^^·;:*^Ϊ··':·'·':>7;^·»;: : -^l·· H; 'J ^ С '' ' THE CARNIVALESQUE IN BEN JONSON’S THREE CITY COMEDIES VOLPONE, THE ALCHEMIST m iy BARTHOLOMEW FAIR A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Humanities and Letters of Bilkent University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Language and Literature G-Ûİ Kur+uLt^ by Gül Kurtuluş April, 1997 Ι62ζ •kSf- I certify that I have read this thesis and that in my opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Language and Literature. Assoc. Prof Ünal Norman (Committee Member) I certify that I have read this thesis and that in my opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Language and Literature. -

Restless Heart

RESTLESS HEART Restless Heart lead singer Larry Stewart can remember the exact moment and place his life began to change forever. “I was driving east on I-40 from West Nashville into town to an appointment,” he recalls. “Back then, I was listening to what we were doing in my Jeep Cherokee every day. I had turned the radio on, and ‘Let The Heartache Ride’ was right in the middle of the acapella intro.” Stewart had been living with the song for a while, and hearing it through his car speakers wasn’t that big of a deal – until he looked at the stereo and saw the numbers 97.9. “It didn’t sink in because I had it in the tape deck for days, then I realized ‘That’s the radio. It’s WSIX.’ I pulled over on the shoulder around White Bridge Road and sat there with my car idling. It was like yesterday.” ‘Yesterday’ has come full circle for Restless Heart. Then one of Nashville’s newest acts, the band is celebrating their 30th Anniversary in 2013, and Dave Innis enjoys the musical ride as much as ever. “I think it’s been an amazing legacy, and it’s been such an honor to have been part of an organization that is still together doing it after thirty years with the same five original guys, and it’s more fun than ever.” John Dittrich, Greg Jennings, Paul Gregg, Dave Innis, and Larry Stewart – the men who make up Restless Heart have enjoyed one of the most successful careers in Country Music history, placing over 25 singles on the charts – with six consecutive #1 hits, four of their albums have been certified Gold by the RIAA, and they have won a wide range of awards from many organizations – including the Academy of Country Music’s Top Vocal Group trophy. -

The Politics of Urban Cultural Policy Global

THE POLITICS OF URBAN CULTURAL POLICY GLOBAL PERSPECTIVES Carl Grodach and Daniel Silver 2012 CONTENTS List of Figures and Tables iv Contributors v Acknowledgements viii INTRODUCTION Urbanizing Cultural Policy 1 Carl Grodach and Daniel Silver Part I URBAN CULTURAL POLICY AS AN OBJECT OF GOVERNANCE 20 1. A Different Class: Politics and Culture in London 21 Kate Oakley 2. Chicago from the Political Machine to the Entertainment Machine 42 Terry Nichols Clark and Daniel Silver 3. Brecht in Bogotá: How Cultural Policy Transformed a Clientist Political Culture 66 Eleonora Pasotti 4. Notes of Discord: Urban Cultural Policy in the Confrontational City 86 Arie Romein and Jan Jacob Trip 5. Cultural Policy and the State of Urban Development in the Capital of South Korea 111 Jong Youl Lee and Chad Anderson Part II REWRITING THE CREATIVE CITY SCRIPT 130 6. Creativity and Urban Regeneration: The Role of La Tohu and the Cirque du Soleil in the Saint-Michel Neighborhood in Montreal 131 Deborah Leslie and Norma Rantisi 7. City Image and the Politics of Music Policy in the “Live Music Capital of the World” 156 Carl Grodach ii 8. “To Have and to Need”: Reorganizing Cultural Policy as Panacea for 176 Berlin’s Urban and Economic Woes Doreen Jakob 9. Urban Cultural Policy, City Size, and Proximity 195 Chris Gibson and Gordon Waitt Part III THE IMPLICATIONS OF URBAN CULTURAL POLICY AGENDAS FOR CREATIVE PRODUCTION 221 10. The New Cultural Economy and its Discontents: Governance Innovation and Policy Disjuncture in Vancouver 222 Tom Hutton and Catherine Murray 11. Creating Urban Spaces for Culture, Heritage, and the Arts in Singapore: Balancing Policy-Led Development and Organic Growth 245 Lily Kong 12.