University of Southern Queensland Behavioural Risk At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2004 General Catalog

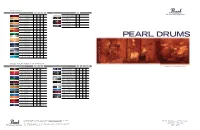

MASTERS SERIES Masters Series Lacquer Finish . Available Colors MMX MRX MHX BRX Masters Series Covered Finish . Available Colors MSX No.100 Wine Red No.400 White Marine Pearl No.102 Natural Maple No.401 Royal Gold No.103 Piano Black No.402 Abalone No.112 Natural Birch No.403 Red Onyx No.122 Black Mist No.404 Amethyst No.128 Vintage Sunburst No.141 Red Mahogany No.148 Emerald Fade No.151 Platinum Mist PEARL DRUMS No.152 Antique Gold No.153 Sunrise Fade m No.154 Midnight Fade o c . No.156 Purple Storm m No.160 Silver Sparkle u r d No.165 Diamond Burst l r No.166 Black Sparkle a e p No.168 Ocean Sparkle . w w w SESSION / EXPORT / FORUM / RHYTHM TRAVELER . Lacquer Finish Available Colors SMX SBX ELX Covered Finish Available Colors EXR EX FX RT www.pearldrum.com No.281 Carbon Mist No.430 Prizm Blue No.290 Vintage Fade No.431 Strata Black No.291 Cranberry Fade No.432 Prizm Purple No.292 Marine Blue Fade No.433 Strata White No.296 Green Burst No.21 Smokey Chrome No.280 Vintage Wine No.31 Jet Black No.283 Solid Black No.33 Pure White No.284 Tobacco Burst No.49 Polished Chrome No.289 Blue Burst No.78 Teal Metallic No.271 Ebony Mist No.91 Red Wine No.273 Blue Mist No.95 Deep Blue No.274 Amber Mist No.98 Charcoal Metallic No.294 Amber Fade No.295 Ruby Fade No.299 Cobalt Fade For more information on these or any Pearl product, visit your local authorized Pearl Dealer. -

J. Dennis Thomas. Concert and Live Music Photography. Pro Tips From

CONCERT AND LIVE MUSIC PHOTOGRAPHY Pro Tips from the Pit J. DENNIS THOMAS Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier 225 Wyman Street, Waltham, MA 02451, USA The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, Oxford, OX5 1GB, UK © 2012 Elsevier Inc. Images copyright J. Dennis Thomas. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangements with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions. This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein). Notices Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary. Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility. To the fullest extent of the law, neither the Publisher nor the authors, contributors, or editors, assume any liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions, or ideas contained in the material herein. -

'The Truth' of the Hillsborough Disaster Is Only 23 Years Late

blo gs.lse.ac.uk http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/archives/26897 ‘The Truth’ of the Hillsborough disaster is only 23 years late John Williams was present on the fateful day in April of 1989. He places the event within its historical and sociological context, and looks at the slow process that finally led to the truth being revealed. I have to begin by saying – rather pretentiously some might reasonably argue – that I am a ‘f an scholar’, an active Liverpool season ticket holder and a prof essional f ootball researcher. I had f ollowed my club on that FA Cup run of 1989 (Hull City away, Brentf ord at home) and was at Hillsborough on the 15 April – f ortunately saf ely in the seats. But I saw all the on- pitch distress and the bodies being laid out below the stand f rom which we watched in disbelief as events unf olded on that awf ul day. Fans carrying the injured and the dying on advertising boards: where were the ambulances? As the stadium and the chaos f inally cleared, Football Trust of f icials (I had worked on projects f or the Trust) asked me to take people f rom the f ootball organisations around the site of the tragedy to try to explain what had happened. It was a bleak terrain: twisted metal barriers and human detritus – scarves, odd shoes and pairs of spectacles Scarve s and flag s at the Hillsb o ro ug h me mo rial, Anfie ld . Cre d it: Be n Suthe rland (CC-BY) via Flickr – scattered on the Leppings Lane terraces. -

Prbis Brainscan

VOLUME 1 ISSUE 3 MAY/JUNE 2011 PRBIS BRAINSCAN LIFE BEYOND ACQUIRED BRAIN INJURY POWELL RIVER BRAIN INJURY SOCIETY Brain Injury 101 – a Marathon for Awareness Date: Saturday June 11, 2011 Location: Pacific Coastal Highway Our new marathon goal - the Pacific Coastal Highway, which includes Highway 101 Brain Injury 101 – a Marathon for Aware- ness For the purpose of: •promoting public awareness of Acquired Brain Injury •raising money to allow us to continue helping our clients and their caregivers. PRBIS BRAINSCAN Page 2 Walk For Awareness of Acquired Brain Injury In 2009 we walked the length of our section of Highway 101. This part of the Pacific Coastal Highway is 56 kilometers in length, start- ing in Lund, passing through Powell River and ending in Saltery Bay, where the ferry connects to the next part of Highway 101. This first walk was completed over 3 days. Participants were clients, professionals and ordinary citizens who wanted to take part in this public awareness project. Money was raised with pledges of sup- port to the walkers as well as business sponsors for each kilometer. For the second year, we offered more options on distance to com- plete – 1, 2, 5 or 10 kilometers, or for the truly fit, the entire 56 kilo- meters. Those who participated did so by walking, running or bicy- cling. We invited not only clients, family and ordinary citizens, but also contacted athletes, young athletes and sports associations to join our cause and complete the 56 kilometers ultra-marathon. _______________________________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________________________ VOLUME 1 ISSUE 3 Page 3 PRBIS BRAINSCAN Page 4 The Too Much Sugar Easter Celebration Linda Boutilier, our resident chocolatier and cake decorator, once again graced our lovely little office with yummy goodness. -

State Coroner's Court

STATE CORONER’S COURT OF NEW SOUTH WALES Inquest: Inquest into the death of six patrons of NSW music festivals, Hoang Nathan Tran Diana Nguyen Joseph Pham Callum Brosnan Joshua Tam Alexandra Ross-King Hearing dates: 8 – 19 July 2019, 10 – 13 September 2019, 19 – 20 September 2019 Date of findings: 8 November 2019 Place of findings: NSW State Coroner’s Court, Lidcombe Findings of: Magistrate Harriet Grahame, Deputy State Coroner Catchwords: CORONIAL LAW – Manner of death, death at music festival, MDMA toxicity, harm minimisation strategies, policing of music festivals, drug checking, drug monitoring schemes, drug education, File numbers: 2018/283593; 2017/381497; 2018/400324; 2019/12787; 2018/283652; 2018/378893; 2018/378893. Representation: Counsel Assisting Dr Peggy Dwyer instructed by Peita Ava-Jones of NSW Department of Communities and Justice Legal Gail Furness SC instructed by Jacinta Smith of McCabe Curwood for NSW Ministry of Health, Ambulance NSW and Western Sydney Local Health District Adam Casselden SC and James Emmett instructed by Nicholas Regener and Louise Jackson of Makinson D’Apice for the Commissioner of Police and four involved Police Officers Simon Glascott of Counsel instructed by Fiona McGinley of Mills Oakley for Medical Response Australia Pty Ltd and Dr Sean Wing Patrick Barry of Counsel instructed in part by Erica Elliot of K & L Gates for the Australian Festivals Association (AFA) Jake Harris of Counsel instructed by Tony Mineo of Avant Law for Dr Christopher Cheeseman and Dr Andrew Beshara Ben Fogarty of Counsel for Simon Beckingham Peter Aitken of Counsel instructed by Summer Dow of DLA Piper for EMS Event Medical and Michael Hammond Laura Thomas of Counsel instructed by Melissa McGrath of Mills Oakley for HSU Events Pty Ltd and Peter Finley Michael Sullivan of Norton Rose Fullbright for FOMO Festival Pty Ltd Andrew Stewart of Stewart & Associates for Q-Dance Australia Pty Ltd Non-publication orders: This document can be published in its current redacted form. -

Public Health Management at Outdoor Music Festivals"

PUBLIC HEALTH MANAGEMENT AT OUTDOOR MUSIC FESTIVALS CAMERON EARL Ass Dip Health Surveying; Masters in Community and Environmental Health Graduate Certificate in Health Science Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Health Science, School of Public Health Faculty of Health Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane January 2006 2 Thesis Abstract Background Information: Outdoor music festivals (OMFs) are complex events to organise with many exceeding the population of a small city. Minimising public health impacts at these events is important with improved event planning and management seen as the best method to achieve this. Key players in improving public health outcomes include the environmental health practitioners (EHPs) working within local government authorities (LGAs) that regulate OMFs and volunteer organisations with an investment in volunteer staff working at events. In order to have a positive impact there is a need for more evidence and to date there has been limited research undertaken in this area. The research aim: The aim of this research program was to enhance event planning and management at OMFs and add to the body of knowledge on volunteers, crowd safety and quality event planning for OMFs. This aim was formulated by the following objectives. 1. To investigate the capacity of volunteers working at OMFs to successfully contribute to public health and emergency management; 2. To identify the key factors that can be used to improve public health management at OMFs; and 3. To identify priority concerns and influential factors that are most likely to have an impact on crowd behaviour and safety for patrons attending OMFs. -

North Byron Parklands – Trial Period Extension Modification Environmental Assessment

pjep. North Byron Parklands – Trial Period Extension Modification Environmental Assessment March 2017 Environmental Assessment North Byron Parklands Trial Extension Prepared for: North Byron Parklands 126 Tweed Valley Way Yelgun NSW 2483 Prepared by: pjep. pjep environmental planning pty ltd, abn. 73 608 508 176 tel. 02 9918 4366 striving for balance between economic, social and environmental ideals… In association with: PLANNERS NORTH | ABN 56 291 496 553 | p: 1300 660 087 | 3/69 Centennial Circuit Byron Bay NSW 2481 | PO Box 538 Lennox Head NSW 2478 PJEP Ref: North Byron Parklands_EA_Mar17.docx DISCLAIMER This document was prepared for the sole use of North Byron Parklands and the regulatory agencies that are directly involved in this project, the only intended beneficiaries of our work. No other party should rely on the information contained herein without the prior written consent of PJEP Environmental Planning, PLANNERS NORTH and North Byron Parklands. Environmental Assessment North Byron Parklands Trial Extension EXECUTIVE SUMMARY North Byron Parklands (Parklands) operates a cultural events site at Yelgun near Byron Bay. The site is home to two of Australia’s most iconic annual international cultural music festivals, Splendour in the Grass and the Falls Festival Byron. The Parklands site operates under a concept plan approval and project approval, granted by the NSW Planning Assessment Commission (the Commission) on behalf of the Minister for Planning on 24 April 2012 (MP 09_0028). The Commission granted the approvals subject to a 5 year trial period, up to the end of calendar 2017. The approvals allow up to 3 events each year (of up to 35,000 patrons), with a total of up to 10 event days per year. -

G E R a L D I N E C R A

GERALDINE CRAIG 111 Willard Hall Manhattan, KS 66506-3705 [email protected] E DUCATION 1987 - 1989 M.F.A. Fiber, Cranbrook Academy of Art, Bloomfield Hills, MI 1977 - 1982 B.F.A. Textile Design, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS B.F.A. History of Art, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS 1979 - 1980 University of St. Andrews, St. Andrews, Scotland (Philosophy, Art History) P ROF E SSIONAL E X pe RI E NC E 2007 - Professor of Art Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS Associate Dean of the Graduate School (2014-2018) Department Head of Art (2007-2014) Associate Professor of Art (2007-2014) 2001 - 2007 Assistant Director for Academic Programs Cranbrook Academy of Art, Bloomfield Hills, MI Developed annual Critical Studies/Humanities program; academic administration 2005 - Regional Artist/Mentor, Vermont College M.F.A. Program Vermont College, Montpelier, VT 1995 - 2001 Curator of Education/Fine and Performing Arts Wildlife Interpretive Gallery, Detroit Zoological Institute, Royal Oak, MI Develop/manage permanent art collection, performing arts programs, temporary exhibits 1994 - 1995 James Renwick Senior Research Fellowship in American Crafts Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 1990 - 1995 Executive Director Detroit Artists Market, (non-profit art center, est. 1932), Detroit, MI 1990 - 1993 Instructor Fiber Department, College for Creative Studies, Detroit, MI 1990 Instructor Red Deer College, Alberta, Canada 1989 - 1990 Registrar I Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, MI 1987 Associate Producer Lyric Theater, Highline Community College, -

Arguelles Climbs to Victory In2.70 'Mech Everest'

MIT's The Weather Oldest and Largest Today: Cloudy, 62°F (17°C) Tonight: Cloudy, misty, 52°F (11°C) Newspaper Tomorrow: Scattered rain, 63°F (17°C) Details, Page 2 Volume 119, Number 25 Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 Friday, May 7, 1999 Arguelles Climbs to Victory In 2.70 'Mech Everest' Contest By Karen E. Robinson and lubricant. will travel to Japan next year to ,SS!)( '1.1fr: .vOl'S UHI! JR The ramps were divided into compete in an international design After six rounds of competition, three segments at IS, 30, and 4S competition. Two additional stu- D~vid Arguelles '01 beat out over degree inclines with a hole at the dents who will later be selected will 130 students to become the champi- end of each incline. Robots scored compete as well. on of "Mech Everest," this year's points by dropping the pucks into 2.;0 Design Competition. these holes and scored more points Last-minute addition brings victory The contest is the culmination of for pucks dropped into higher holes. Each robot could carry up to ten the Des ign and Engineering 1 The course was designed by Roger pucks to drop in the holes. Students (2,.007) taught by Professor S. Cortesi '99, a student of Slocum. could request an additional ten Alexander H. Slocum '82. Some robots used suction to pucks which could not be carried in Kurtis G. McKenney '01, who keep their treads from slipping the robot body. Arguelles put these finished in second place, and third down the table, some clung to the in a light wire contraption pulled by p\~ce finisher Christopher K. -

Christian Rock Concerts As a Meeting Between Religion and Popular Culture

ANDREAS HAGER Christian Rock Concerts as a Meeting between Religion and Popular Culture Introduction Different forms of artistic expression play a vital role in religious practices of the most diverse traditions. One very important such expression is music. This paper deals with a contemporary form of religious music, Christian rock. Rock or popular music has been used within Christianity as a means for evangelization and worship since the end of the 1960s.1 The genre of "contemporary Christian music", or Christian rock, stands by definition with one foot in established institutional (in practicality often evangelical) Christianity, and the other in the commercial rock music industry. The subject of this paper is to study how this intermediate position is manifested and negotiated in Christian rock concerts. Such a performance of Christian rock music is here assumed to be both a rock concert and a religious service. The paper will examine how this duality is expressed in practices at Christian rock concerts. The research context of the study is, on the one hand, the sociology of religion, and on the other, the small but growing field of the study of religion and popular culture. The sociology of religion discusses the role and posi- tion of religion in contemporary society and culture. The duality of Chris- tian rock and Christian rock concerts, being part of both a traditional religion and a modern medium and business, is understood here as a concrete exam- ple of the relation of religion to modern society. The study of the relations between religion and popular culture seems to have been a latent field within research on religion at least since the 1970s, when the possibility of the research topic was suggested in a pioneer volume by John Nelson (1976). -

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020 1 REGA PLANAR 3 TURNTABLE. A Rega Planar 3 8 ASSORTED INDIE/PUNK MEMORABILIA. turntable with Pro-Ject Phono box. £200.00 - Approximately 140 items to include: a Morrissey £300.00 Suedehead cassette tape (TCPOP 1618), a ticket 2 TECHNICS. Five items to include a Technics for Joe Strummer & Mescaleros at M.E.N. in Graphic Equalizer SH-8038, a Technics Stereo 2000, The Beta Band The Three E.P.'s set of 3 Cassette Deck RS-BX707, a Technics CD Player symbol window stickers, Lou Reed Fan Club SL-PG500A CD Player, a Columbia phonograph promotional sticker, Rock 'N' Roll Comics: R.E.M., player and a Sharp CP-304 speaker. £50.00 - Freak Brothers comic, a Mercenary Skank 1982 £80.00 A4 poster, a set of Kevin Cummins Archive 1: Liverpool postcards, some promo photographs to 3 ROKSAN XERXES TURNTABLE. A Roksan include: The Wedding Present, Teenage Fanclub, Xerxes turntable with Artemis tonearm. Includes The Grids, Flaming Lips, Lemonheads, all composite parts as issued, in original Therapy?The Wildhearts, The Playn Jayn, Ween, packaging and box. £500.00 - £800.00 72 repro Stone Roses/Inspiral Carpets 4 TECHNICS SU-8099K. A Technics Stereo photographs, a Global Underground promo pack Integrated Amplifier with cables. From the (luggage tag, sweets, soap, keyring bottle opener collection of former 10CC manager and music etc.), a Michael Jackson standee, a Universal industry veteran Ric Dixon - this is possibly a Studios Bates Motel promo shower cap, a prototype or one off model, with no information on Radiohead 'Meeting People Is Easy 10 Min Clip this specific serial number available. -

Dorothea Tanning

DOROTHEA TANNING Born 1910 in Galesburg, Illinois, US Died 2012 in New York, US SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2022 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Printmaker’, Farleys House & Gallery, Muddles Green, UK (forthcoming) 2020 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Worlds in Collision’, Alison Jacques Gallery, London, UK 2019 Tate Modern, London, UK ‘Collection Close-Up: The Graphic Work of Dorothea Tanning’, The Menil Collection, Houston, Texas, US 2018 ‘Behind the Door, Another Invisible Door’, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain 2017 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Night Shadows’, Alison Jacques Gallery, London, UK 2016 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Flower Paintings’, Alison Jacques Gallery, London, UK 2015 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Murmurs’, Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York, US 2014 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Web of Dreams’, Alison Jacques Gallery, London, UK 2013 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Run: Multiples – The Printed Oeuvre’, Gallery of Surrealism, New York, US ‘Unknown But Knowable States’, Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco, California, US ‘Chitra Ganesh and Dorothea Tanning’, Gallery Wendi Norris at The Armory Show, New York, US 2012 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Collages’, Alison Jacques Gallery, London, UK 2010 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Early Designs for the Stage’, The Drawing Center, New York, US ‘Happy Birthday, Dorothea Tanning!’, Maison Waldberg, Seillans, France ‘Zwischen dem Inneren Auge und der Anderen Seite der Tür: Dorothea Tanning Graphiken’, Max Ernst Museum Brühl des LVR, Brühl, Germany ‘Dorothea Tanning: 100 years – A Tribute’, Galerie Bel’Art, Stockholm, Sweden 2009 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Beyond the Esplanade