Jethro's Advice in Medieval and Early Modern Jewish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Download

Nisan / The Levantine Review Volume 4 Number 2 (Winter 2015) Identity and Peoples in History Speculating on Ancient Mediterranean Mysteries Mordechai Nisan* We are familiar with a philo-Semitic disposition characterizing a number of communities, including Phoenicians/Lebanese, Kabyles/Berbers, and Ismailis/Druze, raising the question of a historical foundation binding them all together. The ethnic threads began in the Galilee and Mount Lebanon and later conceivably wound themselves back there in the persona of Al-Muwahiddun [Unitarian] Druze. While DNA testing is a fascinating methodology to verify the similarity or identity of a shared gene pool among ostensibly disparate peoples, we will primarily pursue our inquiry using conventional historical materials, without however—at the end—avoiding the clues offered by modern science. Our thesis seeks to substantiate an intuition, a reading of the contours of tales emanating from the eastern Mediterranean basin, the Levantine area, to Africa and Egypt, and returning to Israel and Lebanon. The story unfolds with ancient biblical tribes of Israel in the north of their country mixing with, or becoming Lebanese Phoenicians, travelling to North Africa—Tunisia, Algeria, and Libya in particular— assimilating among Kabyle Berbers, later fusing with Shi’a Ismailis in the Maghreb, who would then migrate to Egypt, and during the Fatimid period evolve as the Druze. The latter would later flee Egypt and return to Lebanon—the place where their (biological) ancestors had once dwelt. The original core group was composed of Hebrews/Jews, toward whom various communities evince affinity and identity today with the Jewish people and the state of Israel. -

Who Were the Kenites? OTE 24/2 (2011): 414-430

414 Mondriaan: Who were the Kenites? OTE 24/2 (2011): 414-430 Who were the Kenites? MARLENE E. MONDRIAAN (U NIVERSITY OF PRETORIA ) ABSTRACT This article examines the Kenite tribe, particularly considering their importance as suggested by the Kenite hypothesis. According to this hypothesis, the Kenites, and the Midianites, were the peoples who introduced Moses to the cult of Yahwism, before he was confronted by Yahweh from the burning bush. Scholars have identified the Cain narrative of Gen 4 as the possible aetiological legend of the Kenites, and Cain as the eponymous ancestor of these people. The purpose of this research is to ascertain whether there is any substantiation for this allegation connecting the Kenites to Cain, as well as con- templating the Kenites’ possible importance for the Yahwistic faith. Information in the Hebrew Bible concerning the Kenites is sparse. Traits associated with the Kenites, and their lifestyle, could be linked to descendants of Cain. The three sons of Lamech represent particular occupational groups, which are also connected to the Kenites. The nomadic Kenites seemingly roamed the regions south of Palestine. According to particular texts in the Hebrew Bible, Yahweh emanated from regions south of Palestine. It is, therefore, plausible that the Kenites were familiar with a form of Yahwism, a cult that could have been introduced by them to Moses, as suggested by the Kenite hypothesis. Their particular trade as metalworkers afforded them the opportunity to also introduce their faith in the northern regions of Palestine. This article analyses the etymology of the word “Kenite,” the ancestry of the Kenites, their lifestyle, and their religion. -

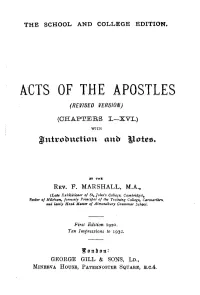

A:Cts of the Apostles (Revised Version)

THE SCHOOL AND COLLEGE EDITION. A:CTS OF THE APOSTLES (REVISED VERSION) (CHAPTERS I.-XVI.) WITH BY THK REV. F. MARSHALL, M.A., (Lau Ezhibition,r of St, John's College, Camb,idge)• Recto, of Mileham, formerly Principal of the Training College, Ca11narthffl. and la1ely Head- Master of Almondbury Grammar School, First Edition 1920. Ten Impressions to 1932. Jonb.on: GEORGE GILL & SONS, Ln., MINERVA HOUSE, PATERNOSTER SQUARE, E.C.4. MAP TO ILLUSTRATE THE ACTS OPTBE APOSTLES . <t. ~ -li .i- C-4 l y .A. lO 15 20 PREFACE. 'i ms ~amon of the first Sixteen Chapters of the Acts of the Apostles is intended for the use of Students preparing for the Local Examina tions of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge and similar examinations. The Syndicates of the Oxford and Cambridge Universities often select these chapters as the subject for examination in a particular year. The Editor has accordingly drawn up the present Edition for the use of Candidates preparing for such Examinations. The Edition is an abridgement of the Editor's Acts of /ht Apostles, published by Messrs. Gill and Sons. The Introduction treats fully of the several subjects with which the Student should be acquainted. These are set forth in the Table of Contents. The Biographical and Geographical Notes, with the complete series of Maps, will be found to give the Student all necessary information, thns dispensing with the need for Atlas, Biblical Lictionary, and other aids. The text used in this volume is that of the Revised Version and is printed by permission of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, but all editorial responsibility rests with the editor of the present volume. -

Preliminary Program Book

PRELIMINARY PROGRAM BOOK Friday - 8:00 AM-12:00 PM A20-100 Status of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex, and Queer Persons in the Profession Committee Meeting Patrick S. Cheng, Chicago Theological Seminary, Presiding Friday - 8:00 AM-12:00 PM Friday - 8:00 AM-1:00 PM A20-101 Status of Women in the Profession Committee Meeting Su Yon Pak, Union Theological Seminary, Presiding Friday - 8:00 AM-1:00 PM Friday - 9:00 AM-12:00 PM A20-102 Public Understanding of Religion Committee Meeting Michael Kessler, Georgetown University, Presiding Friday - 9:00 AM-12:00 PM Friday - 9:00 AM-1:00 PM A20-103 Status of Racial and Ethnic Minorities in the Profession Committee Meeting Nargis Virani, New York, NY, Presiding Friday - 9:00 AM-1:00 PM Friday - 9:00 AM-2:00 PM A20-104 International Connections Committee Meeting Amy L. Allocco, Elon University, Presiding Friday - 9:00 AM-2:00 PM Friday - 9:00 AM-5:00 PM A20-105 Regional Coordinators Meeting Susan E. Hill, University of Northern Iowa, Presiding Friday - 9:00 AM-5:00 PM A20-106 THATCamp - The Humanities and Technology Camp Eric Smith, Iliff School of Theology, Presiding John Crow, Florida State University, Presiding Michael Hemenway, Iliff School of Theology/University of Denver, Presiding Theme: THATCampAARSBL2015 Friday - 9:00 AM-5:00 PM Friday - 10:00 AM-1:00 PM A20-107 American Lectures in the History of Religions Committee Meeting Louis A. Ruprecht, Georgia State University, Presiding Friday - 10:00 AM-1:00 PM Friday - 11:00 AM-6:00 PM A20-108 Religion and Media Workshop Ann M. -

Leadership Characteristics of the Apostle Paul That Can Provide Model to Today's Bbfk Pastors

Guillermin Library Liberty University Lynchbu!1l, VA 24502 LIBERTY BAPTIST THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY LEADERSHIP CHARACTERISTICS OF THE APOSTLE PAUL THAT CAN PROVIDE MODEL TO TODAY'S BBFK PASTORS A Thesis Project Submitted to Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF MINISTRY By Jae Kee Lee Lynchburg Virginia August, 2003 LIBERTY BAPTIST THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY DOCTOR OF MINISTRY THESIS PROJECT APPROVAL SHEET GRADE ~lktJ~1 MENTOR . READER 11 ABSTRACT LEADERSHIP CHARACTERISTICS OF THE APOSTLE PAUL THAT CAN PROVIDE MODEL TO TODAY'S BBFK PASTORS Jae Kee Lee Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary Mentor: Dr. Frank Schmitt The purpose of this project is to understand Paul's leadership characteristics and to apply those characteristics to today's Korean Baptist Bible Fellowship pastors. The project carefully examines Paul's twelve characteristics pertaining to self, interpersonal aspect, spiritual aspect, and functional competency from his writings and his acts reported by Luke. It also analyzes and evaluates current situation ofthe BBFK pastors' leadership based on surveys and interviews. Five practical strategies for the development of the leadership quality of the BBFK pastors are offered. Those strategies will help the pastors demonstrate such leadership characteristics more fully which were found in the apostle Paul. Abstract length: 101 words. III To My Pastor and the Leader of the Korean Baptist Bible Fellowship Dr. Daniel Wooseang Kim IV TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................. -

Kabbalah and the Subversion of Traditional Jewish Society in Early Modern Europe

Kabbalah and the Subversion of Traditional Jewish Society in Early Modern Europe David B. Ruderman Most discussions about notions of authority and dissent in early mod- em Europe usually imply those embedded in Christian traditions, whether Protestant or Catholic. To address these same issues from the perspective of Jewish culture in early modem Europe is to consider the subject from a relatively different vantage point. The small Jewish com- munities of the fifteenth through seventeenth centuries were shaped in manifold ways by the norms and values of the Christian and Moslem host civilizations to which they belonged. Yet, they were also heirs to powerful rabbinic religious and political traditions that structured their social relationships and shaped their attitudes towards divine law, human responsibility, communal discipline, and authority. To examine their uni- verse of discourse in its proper context is to view it both in its own cul- tural terms and in its dialogue and negotiation with the non-Jewish world. No period in Jewish cultural history has undergone more radical refor- mulation and revision by recent scholarship than the early modem; though to what extent conventional schemes of periodization like "early modern," "Renaissance," or "baroque" can be meaningfully applied to the Jewish cultural experience is a question which still engenders much discussion and debate.' Equally problematic is a proper evaluation of the kabbalah, the traditions of Jewish mystical and esoteric experience, 1. For recent discussions of the meaning of the Renaissance and baroque when applied to Jewish culture, see D. B. Ruderman, "The Italian Renaissance and Jewish Thought," in Renaissance Humanism: Foundations and Forms, 3 vols., ed. -

Jethro the Convert

JETHRO THE CONVERT MOSHE REISS INTRODUCTION There is no evidence of any formal conversion process in the Torah. People who wanted to join the nation of Israel left home and lived with the Israelites, 1 thus demonstrating their new affiliation. In the post exilic era we begin to find possible evidence of some form of conversion (Esth. 8:17). Historically, "conversion became common in the centuries after the Babylonian 2 Conquest." Salo Baron estimated the Jewish population at the time of the destruction of the First Temple at 150,000, and by the time of the Second 3 Temple's destruction at eight million. That would require extensive conversions between these periods; when there was little growth in the world population. JETHRO THE OUTSIDER Jethro is introduced in Exodus 2, where he marries off his daughter Zipporah to Moses. His status as a proselyte is connected to a much later appearance, in Exodus 18, when he brings Moses' wife and sons to join the Israelites after their escape from slavery in Egypt. At this reunion, Moses tells Jethro how God took action against the Egyptians. Jethro gives thanks to God for delivering Moses and the Israelite people, and then proclaims: 'Now I know that the Lord is greater than all the gods' (Ex. 18:11). This statement was seen by rabbinic commentators as an indication of Jethro's conversion to Judaism (TB Zevahim 116a; Sanhedrin 103b-104a). The timing of Jethro's arrival is a matter for discussion by the commentators, since it is stated that he meets Moses at the mount of God (Ex. -

Relazioni a Tema Libero

RELAZIONI A TEMA LIBERO Andreina Contessa LA RAPPRESENTAZIONE DELL’ARCA DELL’ALLEANZA NEI MANOSCRITTI EBRAICI E CRISTIANI DELLA SPAGNA MEDIEVALE L’arca dell’alleanza e` uno dei motivi ico- un periodo che va dalla fine del secolo XIII al nografici maggiormente raffigurati nell’arte tardo XV, nelle quali vengono ordinatamente ebraica antica e medievale. Simbolo dell’al- assemblati gli oggetti del santuario e del Tem- leanza e dell’incontro spirituale tra l’uomo e pio 1. L’esempio piu` antico e` una Bibbia di To- Dio, questo cofano di legno di acacia rivestito ledo del 1277 che si trova attualmente presso di oro puro dentro e fuori, sormontato dai che- la Biblioteca Palatina di Parma (MS 2668, rubini era custodito nella parte piu` interna e fols. 7v-8) 2. Sui due fogli gli oggetti sono di- inaccessibile del Santuario descritto nell’Esodo sposti in modo arbitrario, non legato cioe` alla (37,1-9) e poi nel Tempio. L’arca dell’alleanza, loro disposizione nel Santuario, e sono visti di fatto, e`ilprimo oggetto d’arte del quale par- frontalmente cosı`dacreare un legame tra tutti la la Bibbia, aprendo la lunga lista delle istru- gli elementi, ciascuno accompagnato da una zioni per la costruzione del tabernacolo. Essa e` scritta esplicativa solo parzialmente conserva- descritta nella Bibbia con una minuzia e una ta (Fig. 1). chiarezza straordinarie, eppure essa sara` rap- Soltanto un oggetto e` racchiuso in una presentata visivamente soltanto dopo la sua cornice verde a carattere vegetale: l’arca del- scomparsa, fatto questo che ne accresce il ca- l’alleanza, riconoscibile dalle tavole della Leg- rattere simbolico di oggetto del passato, che di- ge sormontate dai cherubini, denominati ke- viene portatore di una valenza messianica. -

Wisdom - Sophia

Wisdom - Sophia But his delight is in the law of the LORD, And in His law he meditates day and night. He will be like a tree firmly planted by streams of water, Which yields its fruit in its season And its leaf does not wither; And in whatever he does, he prospers. - Psalm 1:2-3+ Spiritual wisdom is godly wisdom which contrasts with worldly wisdom. Study the passage in James below and make a list of the contrasts in. Do the same for 1 Cor 1:1-31, 1 Cor 2:1-16. Godly wisdom is God’s character in the many practical affairs of life. In other words godly wisdom involves living life in the light of the revelation of God’s Will in His Word and applying this knowledge to specific situations. Biblical wisdom is definable as skill for living. God's plan to redeem us destroyed the wisdom of the worldly wise men (1 Cor 1:19). In fact, human wisdom never could comprehend God's plan for salvation (1 Cor 1:21). Paul was not bound by the limits of human wisdom because the Holy Spirit conveyed spiritual wisdom through him (1 Cor 2:13). Human wisdom is totally inadequate to accept God's salvation (1 Cor 3:18,19). Who among you is wise and understanding? Let him show by his good behavior his deeds in the gentleness of wisdom. 14 But if you have bitter jealousy and selfish ambition in your heart, do not be arrogant and so lie against the truth. -

Jewish and Christian Intellectual Encounters in Late Medieval Italy

Poetry, Myth, and Kabbala: Jewish and Christian Intellectual Encounters in Late Medieval Italy Byline: Fabrizio Lelli The nature of a diasporic culture—such as the Jewish Italian one—should be understood as an ongoing process of merging and sharing various intellectual materials derived from both the Jewish and the non-Jewish past and present. Throughout the areas where they settled in the Italian peninsula, Jews have both elaborated their own traditional authorities and borrowed non-native elements from the surrounding cultures, influencing the latter in their turn. In Italy, where Jews had established thriving communities since Roman times, the intellectual cooperation with the non-Jewish society was always especially strong throughout the centuries, in part due to the fact that the Jewish population never became numerically significant, therefore being largely exposed to the cultural influence of the majority. The small Italian communities kept in constant contact with one another and with major centers of Jewish knowledge outside of Italy—especially when they had to solve juridical or religious questions, which often derived from the merging of non-indigenous Jewish groups into the local ones. Italian Jews moved around, for commercial and educational purposes: often in the double identity of traders and scholars, sometimes as talented physicians or renowned philosophers. By wandering about the whole peninsula—and sometimes reaching to farther destinations—they circulated the products of their variegated formation, becoming cultural mediators among Jews and between Jews and non-Jews. They could influence their interlocutors orally or address them with letters or treatises, written in Hebrew, Latin, or the local vernacular languages. -

Exodus 18:20

Exodus 17:8-11 (NASB) Then Amalek came and fought against Israel at Rephidim. 9 So Moses said to Joshua, “Choose men for us and go out, fight against Amalek. Tomorrow I will station myself on the top of the hill with the staff of God in my hand.” 10 Joshua did as Moses told him, and fought against Amalek; and Moses, Aaron, and Hur went up to the top of the hill. 11 So it came about when Moses held his hand up, that Israel prevailed, and when he let his hand down, Amalek prevailed. Exodus 17:12-13 (NASB) But Moses’ hands were heavy. Then they took a stone and put it under him, and he sat on it; and Aaron and Hur supported his hands, one on one side and one on the other. Thus his hands were steady until the sun set. 13 So Joshua overwhelmed Amalek and his people with the edge of the sword. Exodus 18:8-12 (NASB) Moses told his father-in-law all that the Lord had done to Pharaoh and to the Egyptians for Israel’s sake, all the hardship that had befallen them on the journey, and how the Lord had delivered them. 9 Jethro rejoiced over all the goodness which the Lord had done to Israel, in delivering them from the hand of the Egyptians. 10 So Jethro said, “Blessed be the Lord who delivered you from the hand of the Egyptians and from the hand of Pharaoh, and who delivered the people from under the hand of the Egyptians. -

Christology Lesson 4 Old Testament Appearances Of

Christology Lesson 4 Old Testament Appearances of Christ Theophany is a combination of 2 Greek words, “theos” which means “God” and “epiphaneia” which means “a shining forth,” or “appearance” and was used by the ancients to refer to an appearance of a god to men (Vine’s, “appear” in loc.). In theology, the word “theophany” refers to an Old Testament appearance of God in visible form. Christophany is by definition an Old Testament appearance of Christ, the second person of the Trinity. Most theophanies (Old Testament appearances of God) are Christophanies (Old Testament appearances of Christ). We will examine some of these Christophanies and see how to discern which ones are actually appearances of Christ or not. Dr. John Walvoord in his great book, Jesus Christ Our Lord, makes the following statement about these Old Testament appearances. “It is safe to assume that every visible manifestation of God in bodily form in the Old Testament is to be identified with the Lord Jesus Christ.” (Walvoord, 54) In John 8, Jesus made the statement that Abraham rejoiced to see His day. Earlier we asked the question, “Did Abraham meet the pre-incarnate Jesus?” (Pre-incarnate = before the incarnation, or before Jesus’ birth by Mary in Bethlehem.) Jesus’ enemies understood the implications of His statement and questioned him about it. They were so enraged by Jesus’ claim to be older than Abraham that they picked up stones to try and stone Him to death. In this chapter we will investigate that question. (We could also ask, “Did Moses ever meet the pre-incarnate Christ?”) Let’s look at a list of Scriptures that have been compiled by Bible teachers over the years that seem to be Christophanies.