Deadline 5 Submission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The EVOLUTION of an AIRPORT

GATWICK The EVOLUTION of an AIRPORT JOHN KING Gatwick Airport Limited and Sussex Industrial Archaeology Society _SUSSEX_ INDUSTRIAL HISTORY journal of the Sussex Industrial Archaeology Society GATWICK The EVOLUTION of an AIRPORT john King Issue No. 16 Produced in conjunction with Gatwick Airport Ltd. 1986 ISSN 0263 — 5151 CONTENTS 1 . The Evolution of an Airport 1 2 . The Design Problem 12 3. Airports Ltd .: Private to Public 16 4 . The First British Airways 22 5. The Big Opening 32 6. Operating Difficulties 42 7. Merger Problems 46 8. A Sticky Patch 51 9. The Tide Turns 56 10. The Military Arrive 58 11 . The Airlines Return 62 12. The Visions Realised 65 Appendix 67 FOREWORD Air Marshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC This is a story of determination and endeavour in the face of many difficulties — the site, finance and "the authorities" — which had to be overcome in the significant achievement of the world's first circular airport terminal building . A concept which seems commonplace now was very revolutionary fifty years ago, and it was the foresight of those who achieved so much which springs from the pages of John King's fascinating narrative. Although a building is the central character, the story rightly involves people because it was they who had to agonise over the decisions which were necessary to achieve anything. They had the vision, but they had to convince others : they had to raise the cash, to generate the publicity, to supervise the work — often in the face of opposition to Gatwick as a commercial airfield. -

Eternal Lies Addendum – Airports

ETERNAL LIES ADDENDUM – AIRPORTS When I originally ran Eternal Lies, I semi-coincidentally included a couple of local airports. This was primarily because (a) I wanted to make the opening scene really specific and filled with lots of historical details in order to immediately begin immersing the players into the time period and (b) while searching for visual references of DC-3 planes for the Silver Sable I stumbled across this amazing photo: In any case, roughly two-thirds of the way through running the campaign, I realized that getting very specific with each airport they arrived at was a very effective technique this type of campaign. Compared to using a sort of “generic airport”: It made the arrival at each location memorable and distinct, creating a clear starting point for each regional scenario. It immediately established the transition in environment and culture. It transforms arrival and — perhaps even more importantly — departure into a scene which has been much more specifically framed. This seemed to encourage meaningful action (by both the PCs and the NPCs) to gravitate towards the airports, which had the satisfying consequence of frequently syncing character arcs and dramatic arcs with actual geography and travel itinerary. In other words, it’s true what they say. First impressions are really important, and it turns out that in a globe-hopping campaign the airports are your first impressions. Now that I’m running the campaign again, therefore, one of the things I prioritized was assembling similarly specific research on the other airports in the campaign. (As with other aspects of the campaign, I find that using historically accurate details seems to be both heighten immersion and create a general sense of satisfaction both for myself and from my players.) As an addendum to the Alexandrian Remix of Eternal Lies, I’m presenting these notes in the hopes that other GMs will find it useful. -

EPHRAIM Written by Michael Skinner I Do Not Suppose

EPHRAIM Written by Michael Skinner I do not suppose many people in Penshurst will know me – or remember me, but my name is still just visible on the board over the entrance to the Post Office (formerly The Forge): I am described as SMITH & COACH BUILDER, Agent for agricultural implements. How much longer that inscription will last I cannot imagine, having been painted more than 100 years ago. Illustration by kind permission of Richard Wheatland www.richardwheatland.com Allow me to introduce myself: my name is John Ephraim SKINNER. I was born in November, 1872, at Wadhurst, East Sussex, the eldest son of a couple of farm workers. My father, Thomas, was a ploughman; my mother was just 20 years old when I was born. To be the eldest of 13 children gives anyone some position in life, and so it is no surprise that I grew up feeling rather responsible, not to say patronising towards my younger brothers and sisters. Look at me in the photograph, which I reproduce here. I could not help wearing a suit and butterfly collar – it was prescribed for me, but I did not object. Mind you – it was Sunday wear: we are in the days when everyone had to attend church, and had to dress formally – collar and tie, waistcoat, boots. How on earth do you think an agricultural worker and his wife could feed and clothe such a large family on their pathetic income? I cannot remember passing down clothes to younger boys when I outgrew them; I cannot ever remember having new clothes bought for me. -

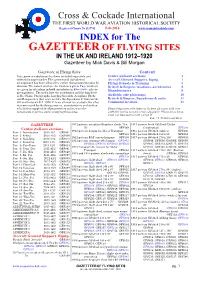

Gazetteer of Flying Sites Index

Cross & Cockade International THE FIRST WORLD WAR AVIATION HISTORICAL SOCIETY Registered Charity No 1117741 Feb.2016 www.crossandcockade.com INDEX for The GAZETTEER OF FLYING SITES IN THE UK AND IRELAND 1912–1920 Gazetteer by Mick Davis & Bill Morgan Gazetteer of Flying Sites Content Data given in tabulations has been included separately and Centre pull-out sections 1 indexed by page number The conventional alphabetical Aircraft Ground Support, Equip. 1 arrangement has been adhered to, rather than presenting sites by Flying Schools & Training 3 function. The names used are the final ones given. Page numbers British & Empire, locations, aerodromes 5 are given for site plans in bold and photos in blue italic, photos Manufacturers 9 given priority. The index lists the aerodromes and the hundreds of Site Plans, Photographs, Landing Grounds, Aeroplane Sheds Airfields, site plan maps 10 and Hangar sites that were used by the Squadrons & Units in the British & Empire, Squadrons & units 11 UK and Ireland 1912–1920. It is an attempt to catalogue the sites Command location 18 that were used by the flying services, manufacturers and civilian schools that supplied the flying services and to trace the Please help correct the index as its been 25 issues with over movements of service units occupying those sites. 3300 line entries so a few errors slipped in Please let us know what you find and we will correct it. Feb. 17, 2016 Derek Riley GAZETTEER 1912 pattern aeroplane/Seaplane sheds, 70 x 1917 pattern brick GS Shed (Under 70' GFS169 Constrution) -

Leigh in the War 1939-45

LEIGH IN THE WAR 1939-45 Leigh and District Historical Society Occasional Paper No. 2 Foreword The Leigh and District Historical Society has been concerned for some time that there has been no record of the impact of the Second World War on the village and people of Leigh. Many years have elapsed and the memories of these events, though still clear in many peoples’ minds, are inevitably beginning to fade. We have been aware that time was running out. We have therefore been fortunate that Morgen Witzel, a Canadian researcher who has lived in the village for several years, has offered to pull together all the available information. There are many people still in the village who lived here during the war and a number of them, together with others who had moved away but were tracked down through the local media or by word of mouth, were interviewed by Morgen. We are most grateful to them for sharing their memories. Their information has been supplemented by material from the village ARP log, which was kept meticulously right through the war and had been retained by the parish council in their safe; this proved to be a fascinating document. Local newspaper archives, particularly the Tonbridge Free Press, and official documents kept at the Public Record Office in Kew provided further information, and more valuable insight into the period was gained from the diaries of Sir Eric Macfadyen who lived at Meopham Bank and owned land in the parish of Leigh. Information from all of these sources is included in this book and has been consolidated onto a map of the parish which is reproduced inside the back cover. -

Penshurst Circular Via Bough Beech Walk

Saturday Walkers Club www.walkingclub.org.uk Penshurst Circular via Bough Beech walk Popular bird-watching site in the Eden Valley and attractive Kent villages Length Main Walk: 21½ km (13.4 miles). Five hours 15 minutes walking time. For the whole excursion including trains, sights and meals, allow at least 9½ hours. Short Walk 1, omitting Penshurst village: 15½ km (9.6 miles). Three hours 45 minutes walking time. Short Walk 2, also omitting Chiddingstone: 14¾ km (9.2 miles). Three hours 30 minutes walking time. OS Map Explorer 147. Penshurst Station (in Chiddingstone Causeway, TQ519467) is in Kent, 7 km W of Tonbridge. Toughness 5 out of 10 (3 for the Short Walks). Features This walk starts through low-lying farmland interspersed with patches of woodland. At Bore Place it makes use of the farm's permissive trails to reach one of the few viewpoints over Bough Beech Reservoir, a large body of water which is surprisingly well screened from public footpaths in the vicinity. The reservoir was created by damming one of the streams flowing down from the Greensand Hills, but is now mostly replenished with water abstracted from the River Eden. The walk continues across the causeway at the northern end of the reservoir where there are good opportunities for bird-watching, but the site's status as a designated nature reserve is uncertain since Kent Wildlife Trust withdrew from its managment in July 2020. After a loop around the western side of the reservoir the walk comes to the first of two possible lunch pubs, in the hamlet of Bough Beech. -

Four Decades Airfield Research Group Magazine

A IRFIELD R ESEARCH G ROUP M AGAZINE . C ONTENTS TO J UNE 2017 Four Decades of the Airfield Research Group Magazine Contents Index from December 1977 to June 2017 1 9 7 7 1 9 8 7 1 9 9 7 6 pages 28 pages 40 pages © Airfield Research Group 2017 2 0 0 7 2 0 1 7 40 pages Version 2: July 2017 48 pages Page 1 File version: July 2017 A IRFIELD R ESEARCH G ROUP M AGAZINE . C ONTENTS TO J UNE 2017 AIRFIELD REVIEW The Journal of the Airfield Research Group The journal was initially called Airfield Report , then ARG Newsletter, finally becoming Airfield Review in 1985. The number of pages has varied from initially just 6, occasio- nally to up to 60 (a few issues in c.2004). Typically 44, recent journals have been 48. There appear to have been three versions of the ARG index/ table of contents produced for the magazine since its conception. The first was that by David Hall c.1986, which was a very detailed publication and was extensively cross-referenced. For example if an article contained the sentence, ‘The squadron’s flights were temporarily located at Tangmere and Kenley’, then both sites would appear in the index. It also included titles of ‘Books Reviewed’ etc Since then the list has been considerably simplified with only article headings noted. I suspect that to create a current cross-reference list would take around a day per magazine which equates to around eight months work and is clearly impractical. The second version was then created in December 2009 by Richard Flagg with help from Peter Howarth, Bill Taylor, Ray Towler and myself. -

Garter Banners

Garter Banner Location (updated March 2019) Living Knights and Ladies of the Order are shown in bold Sovereigns of the Order 1901 - Edward VII - The Deanery, Windsor Castle 1910 – George V – above his tomb, Nave of St George’s Chapel 1936 – George VI - above The Queen’s stall, St George’s Chapel Ladies of the Garter 1901 - Queen Alexandra – the Deanery, Windsor Castle 1910 - Queen Mary – above her tomb St George’s Chapel 1936 - Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother – Clarence House 1994 – Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands 1958 – Queen Juliana of the Netherlands 1979 – Queen Margrethe of Denmark – St George’s Chapel 1989 – Princess Beatrix of the Netherlands – St George’s Chapel 1994 – HRH The Princess Anne (Princess Royal) – St George’s Chapel 2003 – HRH Princess Alexandra – St George’s Chapel Companions of the Order Queen Elizabeth II appointments - Lady Mary Peters – not yet in place - Marquess of Salisbury – not yet in place - King Willem-Alexander of the Netherlands – not yet in place 1011 – Lady Mary Fagan – St George’s Chapel 1010 – Viscount Brookeborough – St George’s Chapel 1009 – King Felipe VI of Spain - St George’s Chapel 1008 – Sir David Brewer – St George’s Chapel 1007 – Lord Shuttleworth – St George’s Chapel 1006 – Baron King of Lothbury – St George’s Chapel 1005 – Baroness Manningham-Buller - St George’s Chapel 1004 - Lord Stirrup – St George’s Chapel 1003 – Lord Boyce – St George’s Chapel 1002 – Lord Phillips of Worth Matravers – St George’s Chapel 1001 – Sir Thomas Dunne – St George’s Chapel 1000 – HRH Prince William of -

Museum News Eden Valley Museum Newsletter Issue Number 19 November 2005

Museum News Eden Valley Museum Newsletter www.evmt.org.uk Issue Number 19 November 2005 The Eden Valley Museum – everywhere has a story to tell Photo: Barry Duffield Editorial Chairman of the Edenbridge and District Amenity Society, succeeding John Irwin. Welcome to the latest issue of our Originally from Yorkshire, he has lived here newsletter, in a slightly new, and I hope, for more than 30 years, having married improved, format. Thank you TOPFOTO Joanna Talbot, whose family is intrinsically for your help! linked with the history of Markbeech. Their The Museum is certainly becoming very house, Edells, was a small farm in the 14th skilled at putting on wonderful exhibitions, century and shares the same name root as with last year’s, devoted to Winston Edenbridge. Churchill, being followed by our current Alan is able to work locally because Hever nostalgic reproduction of what World War II resident, well-known photographer John meant for those who lived – and tragically Topham, passed his business to Alan in died – during it. 1975, and, now called Topfoto.co.uk, it is You will read much more about this side of located in Fircroft Way. our activities in this issue: we are rightly TOPFOTO is Europe’s largest on-line proud of what members have achieved, but, supplier of photographs, with a worldwide of course, we should also remember all the clientele. In addition to their own resources, other aspects of the life of our museum – they have access to more than 12 million the research, the cataloguing of documents images. It was thanks to TOPFOTO that and photographs, the courses, the fun and the Museum was able to put on last year’s educational activities for children, the shop, highly successful Churchill exhibition, the outside visits and the social and fund- providing the photographs and mounting raising activities. -

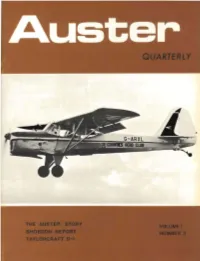

Auster Forum Page 82

q we have moved! 40, Turnstone Gardens Chilworth Park Lordswood Southampton Hants Sal BEW Telephone; Rownhams 5056 OVER 500 MEMBERS IN 15 COUNTRIES have joined the INTERNATIONAL AUSTER PilOT CLUB uster QUARTERLY , Volume 1 Number3 Autumn 1975 Editor: Michael Draper Editorial Office: 40, Turnstone Gardens, Chilworth Park, Lordswood. Southampton S01 8EW. Contents Introduction page 58 Obituary page 58 The Auster Story - Part 3 page 60 I.A.P.C. Fly-In Shobdon page 68 Taylorcraft Model Df 1 - Part 2 page 76 Auster Forum page 82 Front cover: The Terrier 1, G-ARXL was used at Back cover: The final AOP.9 and the last fixed-wing Blackbushe by the Three Counties Aero aeroplane built at Leicester for the Army Club during the mid-sixties, and is seen wasXS238. here crossing the threshold to the airport's main 26 Runway. Auster Quarterly is published in co-operation with the International Auster Pilot Club during February, May, August and November. The subscription rate for the four issues of 1975 is £2 .84 post-paid, cheques or money orders being payable to Auster Quarterly. The editor will be pleased to receive any articles or photographs intended for publication, but only if a stamped addressed envelope is supplied, can these be returned. Neither the Editor nor the International Auster Pilot Club necessarily agrees with opinions expressed by contributors. Printed by Hadfield Print Services, Ltd., 43 Pikes Lane, Glossop, Derbyshire SK13 SED. 57 INTRODUCTION I n order to function properly next year, Auster Quarterly has been forced to slightly re-adjust its thinking habits. -

The Meadoword, July 2013

July 2013 Volume 31, Number 7 The To FREE Meadoword MeaThe doword PUBLISHED BY THE MEADOWS CO mm UNITY ASSO C IATION TO PROVIDE INFOR M ATION AND EDU C ATION FOR MEADOWS RESIDENTS MANASOTA, MANASOTA, FL U.S. POSTAGE PRESORTED STANDARD PERMIT 61 PAID 2 The Meadoword • July 2013 MCA BOARD Notes From the OF DIRECTORS Bob Friedlander, President President’s Desk Dr. Bill Grubb, Vice President Marvin Glusman, Treasurer By Bob Friedlander—MCA President Bill Hoegel, Secretary Claire Coyle An Invitation… from a member standpoint is that the past, the Assembly has proven a most Jo Evans Assembly is to provide a community effective way to feel the pulse of the Joy Howes The MCA as you know it today forum for deliberate and responsible community. Give it a try and attend. Dr. Harry Shannon has undergone many changes since consideration of important issues Another alternative to John Spillane Taylor Woodrow Homes’ initial affecting the membership—thus, communicate your constructive ideas concept. That’s history. Today the giving guidance to the Board of is through a note to the Board or a visit COMMITTEES association has to operate under two Directors for future action or policy to the MCA Community Center. In Assembly of Property Owners major documents—Chapter 720, consideration. most instances, the response will not be Ginny Coveney, Chairperson Homeowners Associations, of the If you are unaffiliated with a immediate but one will be forthcoming, Claire Coyle, Liaison 2012 Florida Statues and the member- condo association or an HOA, your either verbally or written, generally Budget and Finance approved documents as amended. -

Aircraft Noise Complaints

Finance and Corporate Services Information Management 13 February 2014 FOIA reference: F0001789 Dear XXXX I am writing in respect of your recent request of 16 January 2014, for the release of information held by the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA). Your request: “I am looking to compile manipulatable data on as many aspects of aviation environmental issues as possible, going back to 2000. The requested data would cover noise complaints and aircraft emission data and any other data that would be relevant to these areas”. Our response: In assessing your request in line with the provisions of the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA), we are pleased to be able to provide the information below. The CAA receives noise complaints directly from members of the public. This information will be used as a reference for any contact by the same individual or organisation, as well as for statistical analysis. We have provided an excel spreadsheet relating to these complaints (see attachment one). We have however, removed information that relates to the identity of the complainants. These have been removed in accordance with section 40(2) of the FOIA as to release the information would be unfair to the individuals concerned and would therefore contravene the first data protection principle that personal data shall be processed fairly and lawfully. A copy of this exemption can be found enclosed. Noise complaint summary data from the designated London airports, Heathrow, Gatwick and Stansted going back to 2002 (with the exception of Gatwick that goes back to 2006) can be found in attachment one. This spreadsheet provides a count of the number of noise-related enquiries received per quarter by each airport.