Leigh in the War 1939-45

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The EVOLUTION of an AIRPORT

GATWICK The EVOLUTION of an AIRPORT JOHN KING Gatwick Airport Limited and Sussex Industrial Archaeology Society _SUSSEX_ INDUSTRIAL HISTORY journal of the Sussex Industrial Archaeology Society GATWICK The EVOLUTION of an AIRPORT john King Issue No. 16 Produced in conjunction with Gatwick Airport Ltd. 1986 ISSN 0263 — 5151 CONTENTS 1 . The Evolution of an Airport 1 2 . The Design Problem 12 3. Airports Ltd .: Private to Public 16 4 . The First British Airways 22 5. The Big Opening 32 6. Operating Difficulties 42 7. Merger Problems 46 8. A Sticky Patch 51 9. The Tide Turns 56 10. The Military Arrive 58 11 . The Airlines Return 62 12. The Visions Realised 65 Appendix 67 FOREWORD Air Marshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC This is a story of determination and endeavour in the face of many difficulties — the site, finance and "the authorities" — which had to be overcome in the significant achievement of the world's first circular airport terminal building . A concept which seems commonplace now was very revolutionary fifty years ago, and it was the foresight of those who achieved so much which springs from the pages of John King's fascinating narrative. Although a building is the central character, the story rightly involves people because it was they who had to agonise over the decisions which were necessary to achieve anything. They had the vision, but they had to convince others : they had to raise the cash, to generate the publicity, to supervise the work — often in the face of opposition to Gatwick as a commercial airfield. -

Deadline 5 Submission

Deadline 5 Submission This Deadline 5 submission contains three elements: 1. Need & Operations: Applicant and Public Authority responsibilities pursuant to Case Law Hatton and others v. United Kingdom that shows Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights to apply in cases of aircraft noise. Observations communicated at the Need & Operations Issue Specific Hearing of 21 March 2019. Please note Article 13 of the Human Rights Convention also applies and will be discussed in a future submission 2. Night Flights: Kent County Council’s position on night flights as relate to Gatwick Airport and correspondence with Paul Carter, Leader, Kent County Council regarding the current application 3. Evidence as relates to the above (submitted to the ExA as separate attachments): a. CASE OF HATTON AND OTHERS v. THE UNITED KINGDOM, (Application no. 36022/97), GRAND CHAMBER, European Court of Human Rights b. World Health Organisation Environmental Noise Guidelines c. Kent County Council response to Airports Commission consultation 3 Feb 2015 d. Kent County Council response to UK Airspace Policy Consultation e. Kent County Council submission to Department for Transport consultation on night flights f. Kent County Council policy on Gatwick Airport proposal for a second runway. Need & Operations; Applicant and Public Authority responsibilities pursuant to Case Law Hatton and others v. United Kingdom that shows Article 8 of the European Convention of Human Rights to apply in cases of aircraft noise. Observations from the Need & Operations Issue Specific Hearing I would like to thank the Examining Authority for running an open and transparent process and allowing me this opportunity to speak. -

Eternal Lies Addendum – Airports

ETERNAL LIES ADDENDUM – AIRPORTS When I originally ran Eternal Lies, I semi-coincidentally included a couple of local airports. This was primarily because (a) I wanted to make the opening scene really specific and filled with lots of historical details in order to immediately begin immersing the players into the time period and (b) while searching for visual references of DC-3 planes for the Silver Sable I stumbled across this amazing photo: In any case, roughly two-thirds of the way through running the campaign, I realized that getting very specific with each airport they arrived at was a very effective technique this type of campaign. Compared to using a sort of “generic airport”: It made the arrival at each location memorable and distinct, creating a clear starting point for each regional scenario. It immediately established the transition in environment and culture. It transforms arrival and — perhaps even more importantly — departure into a scene which has been much more specifically framed. This seemed to encourage meaningful action (by both the PCs and the NPCs) to gravitate towards the airports, which had the satisfying consequence of frequently syncing character arcs and dramatic arcs with actual geography and travel itinerary. In other words, it’s true what they say. First impressions are really important, and it turns out that in a globe-hopping campaign the airports are your first impressions. Now that I’m running the campaign again, therefore, one of the things I prioritized was assembling similarly specific research on the other airports in the campaign. (As with other aspects of the campaign, I find that using historically accurate details seems to be both heighten immersion and create a general sense of satisfaction both for myself and from my players.) As an addendum to the Alexandrian Remix of Eternal Lies, I’m presenting these notes in the hopes that other GMs will find it useful. -

EPHRAIM Written by Michael Skinner I Do Not Suppose

EPHRAIM Written by Michael Skinner I do not suppose many people in Penshurst will know me – or remember me, but my name is still just visible on the board over the entrance to the Post Office (formerly The Forge): I am described as SMITH & COACH BUILDER, Agent for agricultural implements. How much longer that inscription will last I cannot imagine, having been painted more than 100 years ago. Illustration by kind permission of Richard Wheatland www.richardwheatland.com Allow me to introduce myself: my name is John Ephraim SKINNER. I was born in November, 1872, at Wadhurst, East Sussex, the eldest son of a couple of farm workers. My father, Thomas, was a ploughman; my mother was just 20 years old when I was born. To be the eldest of 13 children gives anyone some position in life, and so it is no surprise that I grew up feeling rather responsible, not to say patronising towards my younger brothers and sisters. Look at me in the photograph, which I reproduce here. I could not help wearing a suit and butterfly collar – it was prescribed for me, but I did not object. Mind you – it was Sunday wear: we are in the days when everyone had to attend church, and had to dress formally – collar and tie, waistcoat, boots. How on earth do you think an agricultural worker and his wife could feed and clothe such a large family on their pathetic income? I cannot remember passing down clothes to younger boys when I outgrew them; I cannot ever remember having new clothes bought for me. -

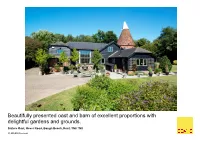

Beautifully Presented Oast and Barn of Excellent Proportions with Delightful Gardens and Grounds

Beautifully presented oast and barn of excellent proportions with delightful gardens and grounds. Slaters Oast, Hever Road, Bough Beech, Kent, TN8 7NX £1,550,000 Freehold SET IN DELIGHTFUL SOUTH -FACING GROUNDS OF ABOUT 1 ACRE WITH COUNTRYSIDE VIEWS • Entrance Hall • 4/5 Reception Rooms • Kitchen/Breakfast Room • Utility Room & Cloakroom • Principal Bedroom with En Suite • 4/5 Further Bedrooms (one with en suite) • Family Bathroom • Landscaped Garden • Gated Driveway • Ample Parking Local Information for Chiddingstone Primary • Slaters Oast is set within the School. hamlet of Bough Beech, • Sporting Facilities: Golf at about 15 minutes away from Hever Castle, Knole and Sevenoaks, with local places Wildernesse in Sevenoaks of interest including the and and Royal Ashdown Reservoir/ Nature Reserve, nearby. Fitness – Nizels Golf Hever Castle and Chartwell. and Country Club in Hildenborough. Edenbridge • Mainline Rail Services: Leisure Centre. Nearby Hildenborough (5.3 miles) & Sevenoaks (7.4 All distances are approximate. miles) to Charing Cross/London Bridge and About this property Cannon Street. Edenbridge Slaters Oast is an attractive (5.6 miles) to London Victoria. converted oast and barn with • Shopping: Sevenoaks and many ‘character’ features, set Tunbridge Wells have in delightful grounds. The extensive shopping facilities, property offers spacious living plus there is a handy accommodation which would Waitrose in Edenbridge (4 also be suitable for a modern miles). home- working lifestyle. • Schools: There is easy access to an excellent • The entrance hall has an selection of schools. oak staircase rising to the first Sevenoaks School, which floor and provides access to offers the IB syllabus, the downstairs cloakroom, a Tonbridge Boys School, study and a family/TV room, Walthamstow Hall (girls), or sixth bedroom. -

The Sevenoaks (Electoral Changes) Order 2014

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2014 No. 1308 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The Sevenoaks (Electoral Changes) Order 2014 Made - - - - 20th May 2014 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) Under section 92(2) of the Local Government and Public Involvement in Health Act 2007( a) (“the Act”) Sevenoaks District Council (“the Council”) made recommendations to the Local Government Boundary Commission for England( b) for the related alteration of the boundaries of district wards within the Council’s area. The Local Government Boundary Commission for England has decided to give effect to the recommendations and, in exercise of the power conferred by section 92(3) of the Act, makes the following Order: Citation and commencement 1. —(1) This Order may be cited as the Sevenoaks (Electoral Changes) Order 2014. (2) This Order comes into force–— (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to the election of councillors, on 15th October 2014; (b) for all other purposes, on the ordinary day of election of councillors in 2015. Interpretation 2. In this Order— “the 2013 Order” means the Sevenoaks District Council (Reorganisation of Community Governance) Order 2013( c); “district ward” means a ward established by article 2 of the District of Sevenoaks (Electoral Changes) Order 2001( d); “ordinary day of election of councillors” has the meaning given by section 37 of the Representation of the People Act 1983( e). (a) 2007 c.28; section 92 has been amended by section 67(1) of, and paragraphs 11 and 32 of Schedule 4 to, the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009 (c. 20) (“the 2009 Act”). -

July/August 2019 July/August

July/August 2019 In this issue: • Medicine past and present • Yoga – creating balance • It’s scarecrow time again! • Hort winners • News from around LINK and about Parish magazine of Four Elms, Hever and Markbeech £1 All Types of Interior & Exterior PAINTING & DECORATING Ray Meades (Speldhurst) 01892 863548 Also General Household Repairs & Maintenance Fully Insured XÄÄtËá VâÑvt~xá Delicious homemade cupcakes using local free range eggs and organic ingredients wherever possible. Our cakes are freshly baked to order ensuring that they taste as good M & M WALKER as they look! We cater for all occasions: birthdays, weddings, corporate events or just because . PAINTING & DECORATING Free local delivery PROPERTY MAINTENANCE SERVICES Contact Alex 07769973426 or at ellascupcakes.net E M O H CEILING & ROOFINGUR CONTRACTORS YO VE O ARTEXINGPR & PLASTERING HOME-REARED FREE-RANGE M PLUMBINGI • HEATING PEDIGREE PORK & LAMB CARPENTRY & JOINERY FALCONHURST ESTATE www.falconhurstestate.co.uk Tel: 01732 863 155 01342 850526 Mobs: 077 742 186 84 • 079 004 207 15 Also Gloucester Old Spot weaners for sale Welcome to the July/August Link Those ‘lazy hazy days of summer’ seem to be taking a long time to arrive this year. However much we know we need the rain, when clouds threaten, we worry about all those carefully planned summer festivities. This issue of the Link is full of village and school events that will fill our diaries. As we enjoy everything on offer in the months ahead, let’s not forget to thank God for all those who work hard to enable all aspects of our life together to flourish – and of course pray for fine weather! The church is firmly at the heart of our communities, and I look forward to many a happy meeting under a clear blue summer sky! Summer is also a time for moving on. -

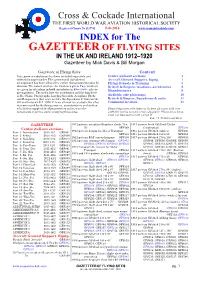

Gazetteer of Flying Sites Index

Cross & Cockade International THE FIRST WORLD WAR AVIATION HISTORICAL SOCIETY Registered Charity No 1117741 Feb.2016 www.crossandcockade.com INDEX for The GAZETTEER OF FLYING SITES IN THE UK AND IRELAND 1912–1920 Gazetteer by Mick Davis & Bill Morgan Gazetteer of Flying Sites Content Data given in tabulations has been included separately and Centre pull-out sections 1 indexed by page number The conventional alphabetical Aircraft Ground Support, Equip. 1 arrangement has been adhered to, rather than presenting sites by Flying Schools & Training 3 function. The names used are the final ones given. Page numbers British & Empire, locations, aerodromes 5 are given for site plans in bold and photos in blue italic, photos Manufacturers 9 given priority. The index lists the aerodromes and the hundreds of Site Plans, Photographs, Landing Grounds, Aeroplane Sheds Airfields, site plan maps 10 and Hangar sites that were used by the Squadrons & Units in the British & Empire, Squadrons & units 11 UK and Ireland 1912–1920. It is an attempt to catalogue the sites Command location 18 that were used by the flying services, manufacturers and civilian schools that supplied the flying services and to trace the Please help correct the index as its been 25 issues with over movements of service units occupying those sites. 3300 line entries so a few errors slipped in Please let us know what you find and we will correct it. Feb. 17, 2016 Derek Riley GAZETTEER 1912 pattern aeroplane/Seaplane sheds, 70 x 1917 pattern brick GS Shed (Under 70' GFS169 Constrution) -

Hoath Cottage Leigh.Docx

Charming and stylishly presented semi-detached cottage with delightful gardens, a paddock and woodland, located in a semi-rural position. Hoath Cottage, Leigh, Tonbridge, Kent, TN11 8HS £795,000 Freehold • Stylishly presented family home • Edge of village location • Character features • Total of about 0.9 acres • Attractive south facing gardens, paddock and woodland • Hildenborough station approx. 2.6 miles Local Information • The triple aspect sitting room • Comprehensive Shopping: features an exposed brick Tonbridge (5.5 miles), Sevenoaks fireplace with wood burner and (6.0 miles), Tunbridge Wells (8.7 double doors leading to the rear miles) & Bluewater (23.7 miles). garden. • Mainline Rail Services: • The light and spacious double Hildenborough (2.6 miles) to London aspect kitchen/breakfast room Bridge/Cannon Street/Charing Cross. comprises a range of wall and Penshurst (1.3 miles) & Leigh (1.1 base units with granite worktops miles) provide a direct service to extending to form a breakfast bar London Bridge via Redhill where and a range of integral connections to London Victoria & appliances. Gatwick Airport are available. • Completing the ground floor is • State Schools: Primary- Various in the family room featuring an Leigh, Hildenborough & Tonbridge. exposed brick fireplace with wood Secondary- Weald of Kent & burner. Tonbridge Girls Grammars & Judd • On the first floor, there are three Boys Grammar in Tonbridge. Various bedrooms, one of which benefits in Sevenoaks & Tunbridge Wells. from a built-in wardrobe, and • Private Schools: Preparatory- another has access to eaves Fosse Bank in Hildenborough; Hilden storage. Oaks, Hilden Grange & The Schools • Completing the accommodation at Somerhill in Tonbridge; Various in is a modern family bathroom with Sevenoaks & Tunbridge Wells. -

A Quaint and Charming Cottage in an Idyllic Rural Location with Impressive

A quaint and charming cottage in an idyllic rural location withBayleys Hill impressive Road, Bough Beech, Edenbridge,views. Kent, TN8 £1,250 pcm, Unfurnished Available from 03.11.2019 Charming and characterful cottage • Stunning views across farm land • Spacious rear garden • Chiddingstone village approx. 2 miles • Sevenoaks station approx. 5 miles Local Information About this property This property is situated in a Set in idyllic Kentish countryside, superb rural setting this semi detached cottage offers approximately 2 miles from the a good sized accommodation with village of Chiddingstone, the added benefit of a large rear providing a village shop/post garden. office, tea room, church and The Castle Inn. Other neighbouring Opening into the entrance porch, villages include Weald and the living room boats an outlook Chiddingstone Causeway. to the front of the property and an open fireplace feature. Adjoining Comprehensive Shopping: is the well appointed kitchen with Sevenoaks - approximately 5 breakfast room which also miles, Tunbridge Wells - benefits from a Aga and access to approximately 8 miles. the rear garden. Mainline Rail Services: Fast From the living room, stairs rise to mainline services to Charing the first floor providing the 2 Cross/Cannon Street from double bedrooms and family Sevenoaks and Hildenborough. bathroom. Other services to London Bridge/Victoria from Edenbridge. To the rear of the house is the www.infotransport.co.uk/trains garden which is laid to lawn and backs onto open fields with rural Primary Schools: Chiddingstone views. and Penshurst.www.kent- pages.co.uk/education. Furnishing Grammar Schools: Weald of Kent Unfurnished Girls, Tonbridge Girls Grammar and Judd Boys Grammar schools Local Authority in Tonbridge. -

Sevenoaks District Council 5 Year Supply of Deliverable Housing Sites 2019/20 to 2023/24 Addendum: September 2019

Sevenoaks District Council 5 Year Supply of Deliverable Housing Sites 2019/20 to 2023/24 Addendum: September 2019 1.1 This addendum has been prepared to supplement the 5 Year Supply of Deliverable Housing Sites [SDC008] submitted alongside the Local Plan in April 2019. 1.2 The 5 Year Supply of Deliverable Housing Sites [SDC008] has been calculated against the local housing need of 707 units per year, in accordance with paragraph 73 of the NPPF. However, the housing requirement set out in the Local Plan is 9,410 units and this figure will replace the local housing need on adoption of the plan, in accordance with paragraph 73 of the NPPF. 1.3 This addendum therefore sets out the calculation of the 5 year supply against the Local Plan housing requirement of 588 units per year. All other aspects of the calculation (application of a 5% buffer, the number of deliverable sites, the qualifying elements of supply) remain as per document SDC008. 1.4 The calculation of the 5 year land supply requirement is set out in the table below. Component Calculation Result (units) A Annual local housing requirement N/A 588 B 5 year requirement A x 5 2,940 C 5% buffer 5% of B 147 D 5 year requirement plus 5% buffer B + C 3,087 1.5 This five year supply of deliverable housing sites assessment identifies a healthy supply of specific deliverable sites in Sevenoaks District that have the capacity to deliver 3,087 residential units in the next 5 years, and 9,410 residential units over the whole of the plan period. -

HC1 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

HC1 bus time schedule & line map HC1 Sundridge - Westerham - Edenbridge - Hugh View In Website Mode Christie School The HC1 bus line (Sundridge - Westerham - Edenbridge - Hugh Christie School) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Cage Green: 7:00 AM (2) Westerham: 3:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest HC1 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next HC1 bus arriving. Direction: Cage Green HC1 bus Time Schedule 43 stops Cage Green Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational Dryhill Lane, Sundridge Tuesday Not Operational Twenties Corner, Sundridge Wednesday 7:00 AM The White Horse, Sundridge Thursday Not Operational Recreation Ground, Sundridge Friday Not Operational New Road, Sundridge Saturday Not Operational The White Hart, Brasted Chart Lane, Brasted HC1 bus Info West End, Brasted Direction: Cage Green Stops: 43 Trip Duration: 75 min Brasted Lodge, Brasted Line Summary: Dryhill Lane, Sundridge, Twenties Corner, Sundridge, The White Horse, Sundridge, Hartley Road Recreation Ground, Sundridge, New Road, London Road, Westerham Civil Parish Sundridge, The White Hart, Brasted, Chart Lane, Brasted, West End, Brasted, Brasted Lodge, Brasted, The Flyers Way Hartley Road, The Flyers Way, The Green, Glebe London Road, Westerham House, Hosey Hill, French Street, Hosey Hill, Mapleton Road, Westerham, Hosey Common Road, The Green Crockham Hill, The Royal Oak, Crockham Hill, Post 8 The Green, Westerham O∆ce, Edenbridge, Edenbridge Town Railway Station, Edenbridge, Leisure