Graham Greene: Political Writer Also by Michael G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Africa: La Herencia De Livingstone En a Burnt-Out Case, De Graham Greene Y El Sueño Del Celta, De Mario Vargas Llosa

ISSN: 0213-1854 'Civilizar' Africa: La herencia de Livingstone en A Burnt-Out Case, de Graham Greene y El sueño del celta, de Mario Vargas Llosa (‘Civilizing’ Africa: Livingstone’s Inheritance in A Burnt-Out Case, by Graham Greene and El sueño del celta, by Mario Vargas Llosa) BEATRIZ VALVERDE JIMÉNEZ [email protected] Universidad Loyola Andalucía Fecha de recepción: 8 de mayo de 2015 Fecha de aceptación: 1 de julio de 2015 Resumen: En este artículo usamos el concepto de „semiosfera‟ desarrollado por el estudioso ruso-estonio Juri Lotman para examinar las relaciones entre las comunidades nativas y las europeas en el Congo belga creadas por Graham Greene en A Burnt-Out Case y por Mario Vargas Llosa en El sueño del celta. Con este análisis tratamos de probar que aunque ambos autores denuncian con sus obras las terribles consecuencias de la colonización europea para los africanos, las comunidades nativas son descritas desde un punto de vista occidental y paternalista. Palabras clave: Congo. Colonización. Lotman. Semiosfera. Europeos. Africanos. Greene. Vargas Llosa. Abstract: In this article the concept of „semiosphere‟, developed by the Russian-Estonian scholar Juri Lotman, is used to examine the relationship between the African and the European communities in the Congo portrayed by Graham Greene in A Burnt-Out Case and by Mario Vargas Llosa in El sueño del celta. With this analysis I will prove that even though both authors denounce the terrible consequences of the European colonization had for the African people, the native communities in the novels are still depicted from a western paternalistic perspective. -

The Post Office Perth Directory

i y^ ^'^•\Hl,(a m \Wi\ GOLD AND SILVER SMITH, 31 SIIG-S: STI^EET. PERTH. SILVER TEA AND COFFEE SERVICES, BEST SHEFFIELD AND BIRMINGHAM (!^lettro-P:a3tteto piateb Crutt mb spirit /tamtjs, ^EEAD BASKETS, WAITEKS, ^NS, FORKS, FISH CARVERS, ci &c. &c. &c. ^cotct) pearl, pebble, arib (STatntgorm leroeller^. HAIR BRACELETS, RINGS, BROOCHES, CHAINS, &c. PLAITED AND MOUNTED. OLD PLATED GOODS RE-FINISHED, EQUAL TO NEW. Silver Plate, Jewellery, and Watches Repaired. (Late A. Cheistie & Son), 23 ia:zc3-i3: sti^eet^ PERTH, MANUFACTURER OF HOSIERY Of all descriptions, in Cotton, Worsted, Lambs' Wool, Merino, and Silk, or made to Order. LADIES' AND GENTLEMEN'S ^ilk, Cotton, anb SEoollen ^\}xxi^ attb ^Mktt^, LADIES' AND GENTLEMEN'S DRAWERS, In Silk, Cotton, Worsted, Merino, and Lambs' Wool, either Kibbed or Plain. Of either Silk, Cotton, or Woollen, with Plain or Ribbed Bodies] ALSO, BELTS AND KNEE-CAPS. TARTAN HOSE OF EVERY VARIETY, Or made to Order. GLOVES AND MITTS, In Silk, Cotton, or Thread, in great Variety and Colour. FLANNEL SHOOTING JACKETS. ® €^9 CONFECTIONER AND e « 41, GEORGE STREET, COOKS FOR ALL KINDS OP ALSO ON HAND, ALL KINDS OF CAKES AND FANCY BISCUIT, j^jsru ICES PTO*a0^ ^^te mmU to ©vto- GINGER BEER, LEMONADE, AND SODA WATER. '*»- : THE POST-OFFICE PERTH DIRECTOEI FOR WITH A COPIOUS APPENDIX, CONTAINING A COMPLETE POST-OFFICE DIRECTORY, AND OTHER USEFUL INFORMATION. COMPILED AND ARRANGED BY JAMES MAESHALL, POST-OFFICE. WITH ^ pUtt of tl)e OTtts atiti d^nmxonn, ENGEAVED EXPRESSLY FOB THE WORK. PEETH PRINTED FOR THE PUBLISHER BY C. G. SIDEY, POST-OFFICE. -

Graham Greene Exhibition Catalogue

The Cherry Record Collection of Josephine Reid’s Papers and Books Relating to Our thanks to the following donors who made the acquisition possible: Paul Almond (1949) GRAHAM GREENE Professor John Stephenson (1953) Professor John-Christopher Spender (1957) Roger Jefferies (1957) Paul Lewis (1958) Peter Buckman (1959) Matthew Nimetz (1960) Doug Rosenthal (1961) Alan James (1962) Stephen Crew (1964) Jim Rogers (1964) Emeritus Professor Paul Crittenden (1965) Alan Heeks (1966) Geoff Wright (1967) Neil Record (1972) Julie Record Richard Jones (1977) Mark Storey (1981) Danny Truell (1982) Alison Roberts (1984) Claire Foster-Gilbert (1984) Virginia Preston (1985) Richard Locke (1985) Jonathan Lewin (1992) Adam Dixon (1994) Sarah Longair (1998) Jo Valentine (2001) Jeff Kulkarni (2001) Sean McDaniel (2002) Alice McDaniel (2003) Blackwell Charitable Trust Friends of the National Libraries ISBN 978-1-78280-500-7 An exhibition held at BALLIOL COLLEGE HISTORIC COLLECTIONS CENTRE 9 781782 805007 > ST CROSS CHURCH, ST CROSS ROAD, OXFORD 25 & 26 April 2015 EXHIBITION AND CATALOGUE BY Naomi Tiley Librarian, Balliol College Anna Sander Archivist, Balliol College FOREWORD BY Sir Anthony Kenny Master of Balliol College 1978–1989 Seamus Perry COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Fellow Librarian, Balliol College Studio portrait of Josephine Reid taken in the late 1940s or early Neil Record 1950s. Photographer unknown. Balliol 1972 Handwriting © Josephine Reid’s Estate Details from postcards from Graham Greene to Josephine Reid © Verdant SA. The organisers are indebted to -

The EVOLUTION of an AIRPORT

GATWICK The EVOLUTION of an AIRPORT JOHN KING Gatwick Airport Limited and Sussex Industrial Archaeology Society _SUSSEX_ INDUSTRIAL HISTORY journal of the Sussex Industrial Archaeology Society GATWICK The EVOLUTION of an AIRPORT john King Issue No. 16 Produced in conjunction with Gatwick Airport Ltd. 1986 ISSN 0263 — 5151 CONTENTS 1 . The Evolution of an Airport 1 2 . The Design Problem 12 3. Airports Ltd .: Private to Public 16 4 . The First British Airways 22 5. The Big Opening 32 6. Operating Difficulties 42 7. Merger Problems 46 8. A Sticky Patch 51 9. The Tide Turns 56 10. The Military Arrive 58 11 . The Airlines Return 62 12. The Visions Realised 65 Appendix 67 FOREWORD Air Marshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC This is a story of determination and endeavour in the face of many difficulties — the site, finance and "the authorities" — which had to be overcome in the significant achievement of the world's first circular airport terminal building . A concept which seems commonplace now was very revolutionary fifty years ago, and it was the foresight of those who achieved so much which springs from the pages of John King's fascinating narrative. Although a building is the central character, the story rightly involves people because it was they who had to agonise over the decisions which were necessary to achieve anything. They had the vision, but they had to convince others : they had to raise the cash, to generate the publicity, to supervise the work — often in the face of opposition to Gatwick as a commercial airfield. -

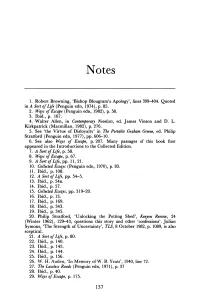

'Bishop Blougram's Apology', Lines 39~04. Quoted in a Sort of Life (Penguin Edn, 1974), P

Notes 1. Robert Browning, 'Bishop Blougram's Apology', lines 39~04. Quoted in A Sort of Life (Penguin edn, 1974), p. 85. 2. Wqys of Escape (Penguin edn, 1982), p. 58. 3. Ibid., p. 167. 4. Walter Allen, in Contemporary Novelists, ed. James Vinson and D. L. Kirkpatrick (Macmillan, 1982), p. 276. 5. See 'the Virtue of Disloyalty' in The Portable Graham Greene, ed. Philip Stratford (Penguin edn, 1977), pp. 606-10. 6. See also Ways of Escape, p. 207. Many passages of this book first appeared in the Introductions to the Collected Edition. 7. A Sort of Life, p. 58. 8. Ways of Escape, p. 67. 9. A Sort of Life, pp. 11, 21. 10. Collected Essays (Penguin edn, 1970), p. 83. 11. Ibid., p. 108. 12. A Sort of Life, pp. 54-5. 13. Ibid., p. 54n. 14. Ibid., p. 57. 15. Collected Essays, pp. 319-20. 16. Ibid., p. 13. 17. Ibid., p. 169. 18. Ibid., p. 343. 19. Ibid., p. 345. 20. Philip Stratford, 'Unlocking the Potting Shed', KeT!Jon Review, 24 (Winter 1962), 129-43, questions this story and other 'confessions'. Julian Symons, 'The Strength of Uncertainty', TLS, 8 October 1982, p. 1089, is also sceptical. 21. A Sort of Life, p. 80. 22. Ibid., p. 140. 23. Ibid., p. 145. 24. Ibid., p. 144. 25. Ibid., p. 156. 26. W. H. Auden, 'In Memory ofW. B. Yeats', 1940, line 72. 27. The Lawless Roads (Penguin edn, 1971), p. 37 28. Ibid., p. 40. 29. Ways of Escape, p. 175. 137 138 Notes 30. Ibid., p. -

Deadline 5 Submission

Deadline 5 Submission This Deadline 5 submission contains three elements: 1. Need & Operations: Applicant and Public Authority responsibilities pursuant to Case Law Hatton and others v. United Kingdom that shows Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights to apply in cases of aircraft noise. Observations communicated at the Need & Operations Issue Specific Hearing of 21 March 2019. Please note Article 13 of the Human Rights Convention also applies and will be discussed in a future submission 2. Night Flights: Kent County Council’s position on night flights as relate to Gatwick Airport and correspondence with Paul Carter, Leader, Kent County Council regarding the current application 3. Evidence as relates to the above (submitted to the ExA as separate attachments): a. CASE OF HATTON AND OTHERS v. THE UNITED KINGDOM, (Application no. 36022/97), GRAND CHAMBER, European Court of Human Rights b. World Health Organisation Environmental Noise Guidelines c. Kent County Council response to Airports Commission consultation 3 Feb 2015 d. Kent County Council response to UK Airspace Policy Consultation e. Kent County Council submission to Department for Transport consultation on night flights f. Kent County Council policy on Gatwick Airport proposal for a second runway. Need & Operations; Applicant and Public Authority responsibilities pursuant to Case Law Hatton and others v. United Kingdom that shows Article 8 of the European Convention of Human Rights to apply in cases of aircraft noise. Observations from the Need & Operations Issue Specific Hearing I would like to thank the Examining Authority for running an open and transparent process and allowing me this opportunity to speak. -

The Third Man"

"THE THIRD MAN" by Graham Greene HIGH ANGLE - FULL SHOT - CITY OF VIENNA The title VIENNA SUPERIMPOSED FADES OUT - commentary commences. COMMENTATOR I never knew the old Vienna before the war, with its - MED. SHOT - STATUE OF A VIOLINIST There is snow on it. COMMENTATOR Strauss music, its glamour and easy charm... MED. SHOT - ROW OF STONE STATUES ornamenting the top of a building. In the b.g. the top of a stone archway. They are snow-sprinkled. COMMENTATOR Constantinople suited... MED. SHOT - SNOW-COVERED STATUE Trees in b.g. COMMENTATOR me better. I really got to know it in the... CLOSE SHOT - TWO MEN talking in the street. COMMENTATOR - classic period of the black... CLOSEUP - SUITCASE opens toward camera, revealing contents consisting of tins of food, shoes, etc. The hands of a man come in from f.g. to take something out. COMMENTATOR - market. We'd run anything... CLOSEUP - HANDS OF TWO PEOPLE standing side by side in the street. The person CL running hands through a pair of silk stockings. COMMENTATOR - if people wanted it enough. CLOSEUP - HANDS OF TWO PEOPLE A woman's hands CL wearing a wedding ring - a man's hands CR holding in RH two small cartons - hands them over to her in exchange for some notes which she hands him. COMMENTATOR - and had the money to pay. CLOSE SHOT - FIVE WRIST WATCHES on a man's wrist from which the coat sleeve is turned back. COMMENTATOR Of course a situation like that - LONG SHOT - CAPSIZED SHIP in shallow water with a drowned body floating on the water CR of it. -

Parodying the Politics of Knowledge

Authors of Truth Writers, Liars, and Spies in Our Man In Havana Jacob Carroll “It takes two to keep something real” - Mr. Wormold in Graham Greene’s Our Man In Havana, 103 - Graham Greene’s celebrated parody of the spy-genre Our Man In Havana opens with a comparison between two characters that are completely unknown to the reader: “‘That nigger1 going down the street,’ said Dr. Hasselbacher standing in the Wonder Bar ‘he reminds me of you, Mr. Wormold’” (7). At first, the reader has no way of evaluating the truthfulness of the similarities Dr. Hasselbacher supposedly sees between Mr. Wormold and the “nigger”: these are two characters that have not yet been described except by the comparison in question. Dr. Hasselbacher’s words assert themselves in the mind of the reader as a statement that – however disorienting it may be as an introduction – cannot be immediately disproved or denied. The accuracy of Dr. Hasselbacher’s comparison is first called into question when the two characters are described in more detail by the narrator: the “nigger” is revealed to be a blind beggar with a limp, while Wormold is revealed to be the clean-cut owner of a Havana vacuum-cleaner shop. However, as the novel’s opening speaker, Dr. Hasselbacher initially details for the reader what the reader cannot perceive otherwise; he offers the only representation of Wormold and the “nigger” available at that juncture. The reader cannot evaluate Dr. Hasselbacher’s comparison as either true or false without first accepting it as a possible representation of both Wormold and the “nigger.” Because the comparison cannot be immediately disproved, it becomes a foil that will re-surface again and again as a potentially true description of these characters’ real natures and qualities. -

Under Other Eyes Constructions of Russianness in Three Socio-Political English Novels

GALINA DUBOVA Under Other Eyes Constructions of Russianness in Three Socio-Political English Novels ACTA WASAENSIA NO 226 LITERARY AND CULTURAL STUDIES 4 ENGLISH UNIVERSITAS WASAENSIS 2010 Reviewers Professor Joel Kuortti Department of English 20014 University of Turku Finland Professor Anthony Johnson Department of English P.O. Box 1000 90014 University of Oulu Finland III Julkaisija Julkaisuajankohta Vaasan yliopisto Lokakuu 2010 Tekijä(t) Julkaisun tyyppi Galina Dubova Monografia Julkaisusarjan nimi, osan numero Acta Wasaensia, 226 Yhteystiedot ISBN Vaasan yliopisto 978–952–476–310–3 Filosofinen tiedekunta ISSN Englannin kieli 0355–2667, 1795–7494 PL 700 Sivumäärä Kieli 65101 VAASA 211 Englanti Julkaisun nimike Toisen silmin: Venäläisyys kolmessa englantilaisessa yhteiskunnallis-poliittisessa romaanissa Tiivistelmä Merkittäväksi osaksi 1900-luvun englantilaisessa kirjallisuudessa on noussut se tapa, miten kansakuntaan ja kansalliseen identiteettiin liittyvä problematiikka esitetään. Tutkimuksessa tarkastellaan kuinka mielikuva Venäjän kansakunnasta ja sen identiteetis- tä on rakennettu ja esitetty kolmessa englanninkielisessä romaanissa. Tarkasteltavat teok- set ovat Joseph Conradin Under Western Eyes (1911), Rebecca Westin The Birds Fall Down (1966) ja Penelope Fitzgeraldin The Beginning of Spring (1988). Teokset on valittu niiden kuvaaman ajan perusteella sekä niiden yhteiskunnallis- poliittisen taustan vuoksi. Ne sijoittuvat Venäjän vallankumousta edeltävään aikaan ja rakentavat kuvaa kansallisesta toiseudesta, alempiarvoisuudesta -

Cervantes and the Spanish Baroque Aesthetics in the Novels of Graham Greene

TESIS DOCTORAL Título Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene Autor/es Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Director/es Carlos Villar Flor Facultad Facultad de Letras y de la Educación Titulación Departamento Filologías Modernas Curso Académico Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene, tesis doctoral de Ismael Ibáñez Rosales, dirigida por Carlos Villar Flor (publicada por la Universidad de La Rioja), se difunde bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Unported. Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden solicitarse a los titulares del copyright. © El autor © Universidad de La Rioja, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2016 publicaciones.unirioja.es E-mail: [email protected] CERVANTES AND THE SPANISH BAROQUE AESTHETICS IN THE NOVELS OF GRAHAM GREENE By Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Supervised by Carlos Villar Flor Ph.D A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At University of La Rioja, Spain. 2015 Ibáñez-Rosales 2 Ibáñez-Rosales CONTENTS Abbreviations ………………………………………………………………………….......5 INTRODUCTION ...…………………………………………………………...….7 METHODOLOGY AND STRUCTURE………………………………….……..12 STATE OF THE ART ..……….………………………………………………...31 PART I: SPAIN, CATHOLICISM AND THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN (CATHOLIC) NOVEL………………………………………38 I.1 A CATHOLIC NOVEL?......................................................................39 I.2 ENGLISH CATHOLICISM………………………………………….58 I.3 THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN -

Introduction

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. Graham Greene (ed.), The Old School (London: Jonathan Cape, 1934) 7-8. (Hereafter OS.) 2. Ibid., 105, 17. 3. Graham Greene, A Sort of Life (London: Bodley Head, 1971) 72. (Hereafter SL.) 4. OS, 256. 5. George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier (London: Gollancz, 1937) 171. 6. OS, 8. 7. Barbara Greene, Too Late to Turn Back (London: Settle and Bendall, 1981) ix. 8. Graham Greene, Collected Essays (London: Bodley Head, 1969) 14. (Hereafter CE.) 9. Graham Greene, The Lawless Roads (London: Longmans, Green, 1939) 10. (Hereafter LR.) 10. Marie-Franc;oise Allain, The Other Man (London: Bodley Head, 1983) 25. (Hereafter OM). 11. SL, 46. 12. Ibid., 19, 18. 13. Michael Tracey, A Variety of Lives (London: Bodley Head, 1983) 4-7. 14. Peter Quennell, The Marble Foot (London: Collins, 1976) 15. 15. Claud Cockburn, Claud Cockburn Sums Up (London: Quartet, 1981) 19-21. 16. Ibid. 17. LR, 12. 18. Graham Greene, Ways of Escape (Toronto: Lester and Orpen Dennys, 1980) 62. (Hereafter WE.) 19. Graham Greene, Journey Without Maps (London: Heinemann, 1962) 11. (Hereafter JWM). 20. Christopher Isherwood, Foreword, in Edward Upward, The Railway Accident and Other Stories (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972) 34. 21. Virginia Woolf, 'The Leaning Tower', in The Moment and Other Essays (NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1974) 128-54. 22. JWM, 4-10. 23. Cockburn, 21. 24. Ibid. 25. WE, 32. 26. Graham Greene, 'Analysis of a Journey', Spectator (September 27, 1935) 460. 27. Samuel Hynes, The Auden Generation (New York: Viking, 1977) 228. 28. ]WM, 87, 92. 29. Ibid., 272, 288, 278. -

Peter Hulme Graham Greene and Cuba

PETER HULME GRAHAM GREENE AND CUBA: OUR MAN IN HAVANA? Graham Greene’s novel Our Man in Havana was published on October 6, 1958. Seven days later Greene arrived in Havana with Carol Reed to arrange for the filming of the script of the novel, on which they had both been work- ing. Meanwhile, after his defeat of the summer offensive mounted by the Cuban dictator, Fulgencio Batista, in the mountains of eastern Cuba, just south of Bayamo, Fidel Castro had recently taken the military initiative: the day after Greene and Reed’s arrival on the island, Che Guevara reached Las Villas, moving westwards towards Havana. Six weeks later, on January 1, 1959, after Batista had fled the island, Castro and his Cuban Revolution took power. In April 1959 Greene and Reed were back in Havana with a film crew to film Our Man in Havana. The film was released in January 1960. A note at the beginning of the film says that it is “set before the recent revolution.” In terms of timing, Our Man in Havana could therefore hardly be more closely associated with the triumph of the Cuban Revolution. But is that association merely accidental, or does it involve any deeper implications? On the fifti- eth anniversary of novel, film, and Revolution, that seems a question worth investigating, not with a view to turning Our Man in Havana into a serious political novel, but rather to exploring the complexities of the genre of com- edy thriller and to bringing back into view some of the local contexts which might be less visible now than they were when the novel was published and the film released.