Ephemera Journal Vol 18 Issue 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LAMP CELEBRATES ITS 16TH ANNIVERSARY Institute for Cinema

LearnAboutMoviePosters.com January 2017 LAMP CELEBRATES ITS 16TH ANNIVERSARY Learn About Movie Posters is celebrating its 16th anniversary this month. We opened with 200 pages in January of 2001 and now have over 200,000 pages online. A special thanks to our wonderful sponsors, including our founding sponsor Bruce Hershenson of emovieposter.com, for their many years of support. Read more about LAMP’s plans for 2017 on page 2. We begin 2017 with two great new sponsors. Institute for Cinema Ephemera Picture Palace Movie Posters FINALLY … a not-for-profit Picture Palace Movie Posters specializes organization dedicated to the in original vintage movie posters, with an preservation of film accessories: emphasis on rare British paper of the 1940s-1970s. Special interests include film posters, papers, and artifacts. Hammer Horror, James Bond 007, Carry On films, Hollywood Classics, Ealing Learn more about this new institute Studios and Monster B movies. and how collectors and dealers can help on page 8. Read more on page 10. New Year Ed-i-torial Let’s start 2017 off right – we have a few different topics that I would like to bring to your attention to start off the year. So, let’s begin with the obvious. LAMP’s 16th Anniversary Online When we first uploaded those 200 pages to start LAMP in January 2001, Sue and I never imagined that we would come this far. LAMP has expanded over 1000 times its beginning size and accomplished some unbelievable mile- stones. We have attacked every major problem area that has been labeled as taboo or unheard of, and systemically created a line of information on them. -

Ephemera-Journal-Vol16-Issue-2

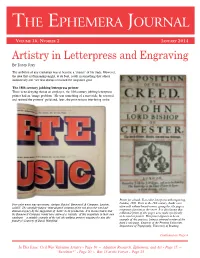

THE EPHEMERA JOURNAL VOLUME 16, NUMBER 2 JANUARY 2014 Artistry in Letterpress and Engraving BY DAVID JURY The ambition of any craftsman was to become a ‘master’ of his trade. However, the idea that craftsmanship might, at its best, result in something that others instinctively call ‘art’ has always remained the unspoken goal. The 18th century jobbing letterpress printer There is no denying that as an employer, the 18th century jobbing letterpress printer had an ‘image problem.’ He was something of a maverick; he resented and resisted the printers’ guild and, later, the print unions interfering in the Poster for a book. Two-color letterpress with engraving, Two-color wood type specimens, Antique Shaded, Bonnewell & Company, London, London, 1692. Prior to the 19th century, books were ca1865. The carefully-judged ‘miss-aligned’ printing of the red gives the word ad- often sold without board-covers, giving the title page a ditional urgency by the suggestion of ‘haste’ in its production. It is inconceivable that temporary function as the cover. It is also known that the Bonnewell Company would have allowed a ‘mistake’ of this magnitude in their own additional prints of title pages were made specifically catalogue – a suitable example of the tail (the jobbing printer) wagging the dog (the to be used as posters. This poster appears to be an foundry)! Courtesy of David Wakefield. example of this practice, being a trimmed version of the book’s title page. Courtesy of the Printing Collection, Department of Typography, University of Reading. Continued on Page 4 1 In This Issue: Civil War Valentine Artistry • Page 10 ~ Adoption Research, Ephemera, and Art • Page 15 ~ “Excelsior!” • Page 20 ~ Box 15 at the Fenyes • Page 23 The Ephemera Journal Dear Members and Friends: Best wishes to everyone for a bountiful New Year filled with health, happiness, and of course, ephemera! Your ESA looks forward to many exciting events, and sincerely hopes you will join in our upcoming activities. -

April | May | June™ 2021 Vol 44 | Ed 2

April | May | June™ 2021 Vol 44 | Ed 2 Antiques, Collectibles, History and Nostalgia for the Pacific Northwest whO’S inSidE Shops, Services & Products By Rusty Rae Howard Road in Auburn. no major damage to structures, her, partly due to road construc- Old Stuff Associate Editor Notes of the demise of the Purple but she notes, “We had a number tion in the area, partly due to the OrEgOn washingtOn of trees that had various limbs pandemic, and partly due to a Vintage, antique and collectable Pelican in Florence are prema- come down in the storm in Febru- lack of energy on her part. “”I’m 78 ALOHA MCMINNVILLE ABERDEEN shops of Old Stuff nation survived ture. Though the previous owner ary. We’ve been working hard and I never know when I’m feel- Susantiques & Collectibles. .......................................9 Homeward Bound Pets and Humane Society ......9 Past & Present Mercantile ....................................... 16 both the COVID-19 closure and a was set to shutter the shop and to get the place back in shape.” . ing up to opening the store,” she Miller’s Antiques ..........................................................8 devastating mid-February winter had sold the cases and shelv- AURORA EDMONDS ing, the building owner, Russ Basl noted she hasn’t been doing said. She said the signs are out, storm that left many sans power Aurora Antiques ...........................................................4 NEWBERG Aurora Antique Pavillion ......................................... 18 Luker, decided to try his hand a great deal of shopping for new so if you’re in the Aloha-Hills- for up to a week. With the winter Aurora Lampworks & Antiques ................................4 Wine Country Antique Mall ......................................9 at the business and it remains product during the first quarter boro-Beaverton area, stop by and weather behind us and COVID- Aurora Mills Architectural ........................................4 LAKEWOOD open. -

The Contribution of Ephemera Dealers

Robert Dalton Harris, Diane DeBlois, David Margolis, and Jean Moss The Contribution of Ephemera Dealers Robert Dalton Harris and Diane DeBlois of aGatherin’, and David Margolis and Jean Moss of Margolis and Moss, explore the relationship between dealers and the libraries and museums that purchase ephemera from them. The two couples who, for over three decades, have specialized in handling ephemera within the rare book world, are from different backgrounds and have divergent strengths, yet agree philosophically on both the importance of ephemera and the complementary role dealers can have with librarians and curators in building collections. In describing their passions, they hope to connect with the collector inside the library and archives profession, as well as to illuminate what it is they actually do as ephemerists, capi- talizing upon the quotidian. Why would an antiquarian choose to specialize in ephemera? Robert Dalton Harris, as a Garbage Hound: My life as a collector began in the hospital—not the one in Salt Lake City where I was born, but five years later in Oregon when I got polio. My neighbor in the children’s ward was totally absorbed in his stamp collection—so I asked my mother about stamps, and we immediately found half a dozen different ones on envelopes from her correspondence. These we purloined, soaked, and counted. Many years later, my grandparents returned to me a letter I wrote them that Christmas, in which I painstakingly accounted for the thirteen stamps I had by then amassed. I was off and running. My mother invited me to take any duplicates I could find from her own col- lection—I remember that there were two—and subsequently we collected together, but in separate albums: gathering from the incoming mail, from gifts, from the post office, from approval selections, and “big bag missionary” mixtures—until my collec- tion exceeded hers and, it was agreed, I became the proud possessor of both. -

Vcrs: the Nde of TV As Ephemera Shawn Michael Glinis University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2015 VCRs: The ndE of TV as Ephemera Shawn Michael Glinis University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Glinis, Shawn Michael, "VCRs: The ndE of TV as Ephemera" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 806. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/806 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VCR”S: THE END OF TV AS EPHEMERA by Shawn Glinis A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Media Studies at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2015 ABSTRACT VCR’S: THE END OF TV AS EPHEMERA by Shawn Glinis The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2015 Under the Supervision of Professor Richard K. Popp Although the VCR is often written about in scholarly literature, it is usually discussed in relation to Hollywood videotapes and rental stores. This study fills a gap in the current literature by presenting a significant history of the VCR in relation to TV during the period regularly referred to as the VCR’s first decade, 1975 to 1985. Specifically, this study is a look at the divergent discourses of the TV industry and the public opinion of TV viewership during this early era that offer insight into how we have come to contemporarily conceptualize TV. -

Hobbies & Crafts Reference Center

Hobbies & Crafts Reference Center Database Coverage List *Titles with 'Coming Soon' in the Availability column indicate that this publication was recently added to the database and therefore few or no articles are currently available. If the ‡ symbol is present, it indicates that 10% or more of the articles from this publication may not contain full text because the publisher is not the rights holder. Please Note: Publications included on this database are subject to change without notice due to contractual agreements with publishers. Coverage dates shown are the intended dates only and may not yet match those on the product. All coverage is cumulative. Due to third party ownership of full text, EBSCO Information Services is dependent on publisher publication schedules (and in some cases embargo periods) in order to produce full text on its products. Source Type ISSN / ISBN Publication Name Publisher Indexing and Indexing and Full Text Full Text PDF Abstracting Abstracting Start Stop Images Start Stop (full page) Book / Monograph 9781592172559 1,2,3 Skein Crochet Annie's Publishing, LLC 09/01/2009 09/30/2009 09/01/2009 09/30/2009 Y Book / Monograph 9781596353336 1,2,3,4 Double-Ended Hook Crochet Annie's Publishing, LLC 01/01/2010 01/31/2010 01/01/2010 01/31/2010 Y Book / Monograph 9781590122105 10 Hour Fashion Knits Annie's Publishing, LLC 01/01/2007 01/31/2007 01/01/2007 01/31/2007 Y Book / Monograph 9781592171217 10-Minute Cards to Give & Share Annie's Publishing, LLC 12/01/2006 12/31/2006 12/01/2006 12/31/2006 Y Book / Monograph 9781596357945 -

Collecting in the Digital Age International Collectors Survey by AXA ART

COLLECTING IN THE DIGITAL AGE International Collectors Survey by AXA ART Results of a worldwide empirical study www.axa-art.de AXA ART Insurance / 2014 INTRODUCTION For more than fifty years, AXA ART has been insuring works of art and other objects of value. Over the decades, we have accompanied collectors from around the world. We have learnt about their attitudes towards collecting, and we strive to be aware of their interests and concerns. All in all, we felt at home within the collectors’ community – until the Internet started to change their habits. We became curious and conducted several dozen long, face-to-face interviews with collectors. The issues which emerged from these dialogues – whilst still hypothetical – were used as the basis for a worldwide online survey. In terms of participation and results, the responses are remarkable; they have been compiled in this publication. Due to the chosen online approach, there is a certain bias in the results, as all communication took place via the Internet. It became evident that the worldwide community of collectors is changing, and that such change is partly driven by the Internet. We hope you find the results as interesting as we did and that you can also benefit from understanding these changing behaviours. Dr. Ulrich Guntram Silke Kastien CEO AXA ART Group Head of Group Marketing Cologne, March 2014 AXA ART AXA ART CONTENTS 4 Art collectors: who collects what, how, why and where? 12 A typology of collectors 14 Type I: art aficionados – collecting out of passion 17 Type II: traditionalists – collecting over generations 20 Type III: investors – collecting for the portfolio 23 Methodology of the Collectors Survey by AXA ART 2 AXA ART AXA ART 3 ART COLLECTORS: WHO COLLECTS WHAT, HOW, WHY AND WHERE? Age groups 30 − 39 40 − 49 up to 29 13% 3% 25% 70 and older 9% 23% 25% 60 − 69 50 − 59 Employment status and gender 1. -

Productivity Orientation and the Consumption of Collectable Experiences

Productivity Orientation and the Consumption of Collectable Experiences ANAT KEINAN RAN KIVETZ This research examines why consumers desire unusual and novel consumption experiences and voluntarily choose leisure activities, vacations, and celebrations that are predicted to be less pleasurable. For example, consumers sometimes choose to stay at freezing ice hotels and to eat at restaurants serving peculiar foods, such as bacon ice cream. We propose that such choices are driven by consumers’ continual striving to use time productively, make progress, and reach accomplishments (i.e., a productivity orientation). We argue that choices of col- lectable (unusual, novel, extreme) experiences lead consumers to feel productive even when they are engaging in leisure activities as they “check off” items on an “experiential check list” and build their “experiential CV.” A series of laboratory and field studies shows that the consumption of collectable experiences is driven and intensified by a (chronic or situational) productivity orientation. Man is so made that he can only find relaxation We propose that consumers are attracted to these activities from one kind of labor by taking up another. and products because they view them as opportunities to col- (Anatole France) lect new experiences and build their “experiential CV.” We explain this phenomenon by the continual striving of many Finally, a to-do list you’ll really want to do. (Advertisment for Mohegan Sun Hotel, Casino, consumers to use time efficiently and productively. This desire and Spa) to accomplish more in less time is so powerful that it not only affects consumers’ performances in vocational (or “pro- ecent marketing trends suggest that many consumers are duction”) settings but can influence their leisure preferences R attracted to unusual and novel consumption experiences and consumption choices as well. -

The Ephemera Journal

THE EPHEMERA JOURNAL VOLUME 19, NUMBER 2 JANUARY 2017 Tattoo Trade Cards: The Ephemera of Electric Art, 1900-1930 BY CARMEN FORQUER-NYSSEN AND DERIN BRAY Tattooing was a hardscrabble business for pioneers of the sources in understanding the history of tattooing and those trade. The advent of the electric tattoo machine in the 1880s who contributed to its early success. saw with it a generation of ambitious tattooers whose fortitude New York trade cards reveal profound insights about the and ingenuity shaped tattooing into a skilled profession. early modernization of tattooing. The New York Bowery, Motivated practitioners of this era steadily broke new from the latter half of the 1880s into the middle of the ground in towns and cities across America—broadening the next century, stood as a major tattooing hub and hotbed of boundaries of their livelihood, while battling the adversities innovation. Illustrious dime show tattooer Samuel F. O’Reilly of an emerging field. Faced with fierce competition, Continued on Page 4 sporadic work, and no doubt discrimination, tattooers carved out a tough existence, inking clients wherever they could: in the backs of pool halls, with carnivals, aboard ships, at dime museums, and in shops located in rough-and- tumble neighborhoods. Because of the itinerant and often underground nature of their work, tattooers were not always captured in customary records; documenting their careers can be a difficult task. Fortunately, many left behind clues, from hand-painted tattoo designs (flash) to photographic portraits of their prized canvases. Some of the best information is found on trade cards. These small pieces of cardstock printed with names, locations, and occasionally graphics are important Figure 1. -

LLMVC EPHEMERA COLLECTION Inventory

LLMVC EPHEMERA COLLECTION Inventory Compiled by Hans Rasmussen Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections Special Collections, Hill Memorial Library Louisiana State University Libraries Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, La. 2011 Latest revision, October 2020 LLMVC EPHEMERA COLLECTION SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, LSU LIBRARIES CONTENTS OF INVENTORY SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................ 3 SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE ....................................................................................... 4 LIST OF SUBGROUPS ..................................................................................................... 4 SUBGROUP DESCRIPTIONS .......................................................................................... 5 INDEX TERMS .................................................................................................................. 7 CONTAINER LIST .......................................................................................................... 10 Use of materials. If you wish to examine items in the ephemera collection, please place a request via the Special Collections Request System. Consult the Container List for location information. Publication. Readers assume full responsibility for compliance with laws regarding copyright, literary property rights, and libel. Proper acknowledgement of LLMVC materials must be made in any resulting writing or publications. The correct form of citation for this manuscript -

First Round Judging - Accepted Entries Posted 06/12/2017 (Adult Home Crafts-Hobbies, Adult Collections Page 1 of 57 and Adult Fiberarts)

First Round Judging - Accepted Entries Posted 06/12/2017 (Adult Home Crafts-Hobbies, Adult Collections Page 1 of 57 and Adult FiberArts) If your name does not appear on this list, we understand your disappointment and encourage you to try again next year. New judges are empanelled each year. First Round Judging does NOT guarantee acceptance for exhibition. Additional judging will follow. Delivery entry tag will be sent to the email address you used during registration. Please check your email inbox and spam folder. You may also generate your own delivery entry tag by entering the same account information you used during registration. http://www.fairjudge.com/fairentrytag.cfm?fairId=ocfair Print your delivery entry tag and bring with you on Saturday, June 24. Review and adhere to the Competition Guide guidelines. http://ocfair.com/howtoenter/crafts-hobbies/ Deliver your accepted entry on Saturday, June 24, 8 am - 6 pm. for Hand Crafts & Hobbies, Fiber Arts, Jewelry Arts - OC Promenade (East entrance) for Collections - Silo Building at Centennial Farm You may designate another person to deliver your accepted entry. We are unable to accept late delivery of entries. One free OC Fair admission ticket per exhibitor; not one per entry. If you have an "entry accepted" for delivery, you will receive your admission ticket at time of entry delivery. You will NOT be eligible to receive another ticket for any non-accepted entries. If "none" of your entries were accepted for exhibition, one admission ticket will be available for pickup at the Guest Services booth at the Main Gate during normal Fair hours. -

Collectible Pipe-Related Ephemera: Here Today, Not Necessarily Gone Tomorrow! by Ben Rapaport

Collectible Pipe-related Ephemera: Here Today, Not Necessarily Gone Tomorrow! By Ben Rapaport To crossover-collectors, this may be for you! There’s lots of collectible stuff in circulation related to tobacco pipes. As Marian Klamkin in 1981(Collectibles: A Compendium) reported: “There are a lot of specialties within this broad field of collecting. They range from tobacco tins to hand-carved pipes, from objects that had no original intrinsic value to things that were very expensive when new.” And among those objects that had no intrinsic value are ephemera, a word many use, but not often understood. Derived from the Greek, ephemeron, meaning short-lived or transitory; the plural ephemera most often refers to printed matter produced for a specific purpose, then discarded when that purpose is achieved. Examples include sheet music, advertisements, postcards, tickets, stock certificates, posters, booklets, brochures, pamphlets, billheads, ledgers, scrapbooks, photographs, and myriad other items, all of them related in a thematic collection by subject, period of history, or other interest. You can get a general idea of what some folks collect by reading “How I Collect” (ephemerasociety.org). This essay is about pipe-related stuff generally classified as ephemeral, e.g., written or printed materials (not books!) not envisioned or intended for long-term preservation or retention. Where to begin? I focus on printed matter—to the exclusion of premium catalogs and store coupons—and a few related collectibles. (Pipe and tobacco factory and retail tobacconist catalogs are the premier reference jewels for a collector, but a detailed discussion of these exceeds the scope of this narrative.) Here’s a laundry list of all the mediums used to promote tobacco products at one time or another.