Descriptions of the Plant Types

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plant List 2016

Established 1990 PLANT LIST 2016 European mail order website www.crug-farm.co.uk CRÛG FARM PLANTS • 2016 Welcome to our 2016 list hope we can tempt you with plenty of our old favourites as well as some exciting new plants that we have searched out on our travels. There has been little chance of us standing still with what has been going on here in 2015. The year started well with the birth of our sixth grandchild. January into February had Sue and I in Colombia for our first winter/early spring expedition. It was exhilarating, we were able to travel much further afield than we had previously, as the mountainous areas become safer to travel. We are looking forward to working ever closer with the Colombian institutes, such as the Medellin Botanic Gardens whom we met up with. Consequently we were absent from the RHS February Show at Vincent Square. We are finding it increasingly expensive participating in the London shows, while re-branding the RHS February Show as a potato event hardly encourages our type of customer base to visit. A long standing speaking engagement and a last minute change of date, meant that we missed going to Fota near Cork last spring, no such problem this coming year. We were pleasantly surprised at the level of interest at the Trgrehan Garden Rare Plant Fair, in Cornwall. Hopefully this will become an annual event for us, as well as the Cornwall Garden Society show in April. Poor Sue went through the wars having to have a rush hysterectomy in June, after some timely results revealed future risks. -

Movement and Habitat Use by Adult and Juvenile Toad-Headed Agama Lizards (Phrynocephalus Versicolor Strauch, 1876) in the Eastern Gobi Desert, Mongolia

Herpetology Notes, volume 12: 717-719 (2019) (published online on 07 July 2019) Movement and habitat use by adult and juvenile Toad-headed Agama lizards (Phrynocephalus versicolor Strauch, 1876) in the eastern Gobi Desert, Mongolia Douglas Eifler1,* and Maria Eifler1,2 Introduction From 0700–1900 h we walked slowly throughout the study area in search of Toad-headed Agama lizards Phrynocephalus versicolor Strauch, 1876 is a (Phrynocephalus versicolor). When a lizard was small lizard (Agamidae) found in desert and semi- sighted, we captured the animal by hand or noose. desert regions of China, Mongolia, Kazakhstan and We then measured the lizard (snout-to-vent length Kyrgyzstan (Zhao, 1999). The species inhabits areas of (SVL; mm) and mass (g) and sexed adults by probing. sparse vegetation and can be relatively common, with Juveniles were too small to sex. Using non-toxic paint reported densities of up to 400 per hectare (Zhao, 1999). pens, we marked each lizard with a unique colour code In spite of its wide distribution and local abundance, for later identification and to avoid recapture or repeat relatively little detailed ecological information is observations. available, particularly in the northern areas of its range. All focal observations occurred on one day (26 We report our ecological observations on a population August). When an animal was sighted, we positioned of P. versicolor in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia with ourselves 3–5 m from the lizard, waited 5 min for regard to their movement and habitat use. the lizard to acclimate to our presence, and then we began a 10-min observation period. -

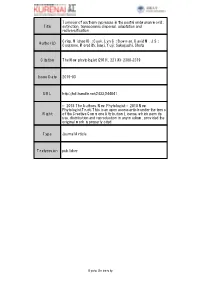

Extinction, Transoceanic Dispersal, Adaptation and Rediversification

Turnover of southern cypresses in the post-Gondwanan world: Title extinction, transoceanic dispersal, adaptation and rediversification Crisp, Michael D.; Cook, Lyn G.; Bowman, David M. J. S.; Author(s) Cosgrove, Meredith; Isagi, Yuji; Sakaguchi, Shota Citation The New phytologist (2019), 221(4): 2308-2319 Issue Date 2019-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/244041 © 2018 The Authors. New Phytologist © 2018 New Phytologist Trust; This is an open access article under the terms Right of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University Research Turnover of southern cypresses in the post-Gondwanan world: extinction, transoceanic dispersal, adaptation and rediversification Michael D. Crisp1 , Lyn G. Cook2 , David M. J. S. Bowman3 , Meredith Cosgrove1, Yuji Isagi4 and Shota Sakaguchi5 1Research School of Biology, The Australian National University, RN Robertson Building, 46 Sullivans Creek Road, Acton (Canberra), ACT 2601, Australia; 2School of Biological Sciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Qld 4072, Australia; 3School of Natural Sciences, The University of Tasmania, Private Bag 55, Hobart, Tas 7001, Australia; 4Graduate School of Agriculture, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan; 5Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan Summary Author for correspondence: Cupressaceae subfamily Callitroideae has been an important exemplar for vicariance bio- Michael D. Crisp geography, but its history is more than just disjunctions resulting from continental drift. We Tel: +61 2 6125 2882 combine fossil and molecular data to better assess its extinction and, sometimes, rediversifica- Email: [email protected] tion after past global change. -

TP7 Gentianales Y Lamiales 2015

TETEÓÓRICORICO PRPRÁÁCTICOCTICO NNºº 77 SUBCLASESUBCLASE :: ASTASTÉÉRIDASRIDAS ORDEN:ORDEN: GENTIANALESGENTIANALES ORDEN:ORDEN: LAMIALESLAMIALES ASIGNATURA Plantas Vasculares Ing. en Recursos Naturales y Medio Ambiente Docentes: María Alicia Zapater Auxiliares Alumnos: Romina Collavino Mirta Quiroga Ana Delgado Mariela Fabbroni Gerardo Gramajo Víctor Aquino Evangelina Lozano Carolina Flores UBICACIUBICACI ÓÓNN TAXONTAXONÓÓMICAMICA Reino: Plantas División: Magnoliófitas Clase: Magnoliópsidas Subclase: Astéridas Orden Gentianales Orden Lamiales ORDEN GENTIANALES -Hojas opuestas o verticiladas. - -Gineceo súpero con varios carpelos soldados. - Posee 4 familias Loganiáceas, Gentianáceas, Apocináceas y Asclepiadáceas. FAMILIA APOCINÁCEAS - Árboles, arbustos o lianas, enredaderas o hierbas, generalmente con látex. Aspidosperma quebracho blanco Nerium oleander Mandevillea - Hojas simples, opuestas y decusadas o verticiladas, raro alternas; coriáceas, a veces con ápice punzante . Vinca Nerium oleander - Inflorescencias axilares o apicales muy variadas, racimosas o cimosas, a veces reducidas a una flor. - Flores actinomorfas o apenas cigomorfas, perfectas, pentámeras. - Corola gamopéla de prefloración contorta, tubulosa, campanulada, hipocrateriforme o infundibuliforme, a veces con apéndices formando una corona. - Androceo con 5 estambres con filamentos cortos unidos al tubo de la corola, anteras libres o unidos y conniventes al estigma, constituyendo un cono estaminal. Cono estaminal A la madurez las anteras se separan Disco nectarífero entre -

Evolution of Angiosperm Pollen. 7. Nitrogen-Fixing Clade1

Evolution of Angiosperm Pollen. 7. Nitrogen-Fixing Clade1 Authors: Jiang, Wei, He, Hua-Jie, Lu, Lu, Burgess, Kevin S., Wang, Hong, et. al. Source: Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 104(2) : 171-229 Published By: Missouri Botanical Garden Press URL: https://doi.org/10.3417/2019337 BioOne Complete (complete.BioOne.org) is a full-text database of 200 subscribed and open-access titles in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Complete website, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/terms-of-use. Usage of BioOne Complete content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non - commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Downloaded From: https://bioone.org/journals/Annals-of-the-Missouri-Botanical-Garden on 01 Apr 2020 Terms of Use: https://bioone.org/terms-of-use Access provided by Kunming Institute of Botany, CAS Volume 104 Annals Number 2 of the R 2019 Missouri Botanical Garden EVOLUTION OF ANGIOSPERM Wei Jiang,2,3,7 Hua-Jie He,4,7 Lu Lu,2,5 POLLEN. 7. NITROGEN-FIXING Kevin S. Burgess,6 Hong Wang,2* and 2,4 CLADE1 De-Zhu Li * ABSTRACT Nitrogen-fixing symbiosis in root nodules is known in only 10 families, which are distributed among a clade of four orders and delimited as the nitrogen-fixing clade. -

Bio 308-Course Guide

COURSE GUIDE BIO 308 BIOGEOGRAPHY Course Team Dr. Kelechi L. Njoku (Course Developer/Writer) Professor A. Adebanjo (Programme Leader)- NOUN Abiodun E. Adams (Course Coordinator)-NOUN NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA BIO 308 COURSE GUIDE National Open University of Nigeria Headquarters 14/16 Ahmadu Bello Way Victoria Island Lagos Abuja Office No. 5 Dar es Salaam Street Off Aminu Kano Crescent Wuse II, Abuja e-mail: [email protected] URL: www.nou.edu.ng Published by National Open University of Nigeria Printed 2013 ISBN: 978-058-434-X All Rights Reserved Printed by: ii BIO 308 COURSE GUIDE CONTENTS PAGE Introduction ……………………………………......................... iv What you will Learn from this Course …………………............ iv Course Aims ……………………………………………............ iv Course Objectives …………………………………………....... iv Working through this Course …………………………….......... v Course Materials ………………………………………….......... v Study Units ………………………………………………......... v Textbooks and References ………………………………........... vi Assessment ……………………………………………….......... vi End of Course Examination and Grading..................................... vi Course Marking Scheme................................................................ vii Presentation Schedule.................................................................... vii Tutor-Marked Assignment ……………………………….......... vii Tutors and Tutorials....................................................................... viii iii BIO 308 COURSE GUIDE INTRODUCTION BIO 308: Biogeography is a one-semester, 2 credit- hour course in Biology. It is a 300 level, second semester undergraduate course offered to students admitted in the School of Science and Technology, School of Education who are offering Biology or related programmes. The course guide tells you briefly what the course is all about, what course materials you will be using and how you can work your way through these materials. It gives you some guidance on your Tutor- Marked Assignments. There are Self-Assessment Exercises within the body of a unit and/or at the end of each unit. -

Phylogeny and Subfamilial Classification of the Grasses (Poaceae) Author(S): Grass Phylogeny Working Group, Nigel P

Phylogeny and Subfamilial Classification of the Grasses (Poaceae) Author(s): Grass Phylogeny Working Group, Nigel P. Barker, Lynn G. Clark, Jerrold I. Davis, Melvin R. Duvall, Gerald F. Guala, Catherine Hsiao, Elizabeth A. Kellogg, H. Peter Linder Source: Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, Vol. 88, No. 3 (Summer, 2001), pp. 373-457 Published by: Missouri Botanical Garden Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3298585 Accessed: 06/10/2008 11:05 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mobot. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. -

Gene Flow and Geographic Variation in Natural Populations of Alnus Acumi1'lata Ssp

Rev. Biol. Trop., 47(4): 739-753, 1999 www.ucr.ac.cr www.ots.ac.cr www.ots.duke.edu Gene flow and geographic variation in natural populations of Alnus acumi1'lata ssp. arguta (Fagales: Betulaceae) in Costa Rica and Panama OIman Murillo) and Osear Roeha2 Instituto Tecnológico de Costa Rica, Escuela de Ing. Forestal.Apartado 159 7050 Cartago, Costa Rica. Fax: 591-4182. e-mail: omurillo@itcr.. ac.cr 2 Universidad de Costa Rica, Escuela de Biología, Campus San Pedro, San José, Costa Rica. e-mail: [email protected] Received 16-IX-1998. Corrected 05-IV-1999. Accepted 16-IV-1999 Abstract: Seventeen natural populations in Costa Rica andPanama were used to asses geneflow and geographic patternsof genetic variation in tbis tree species. Gene flow analysis was based on the methods of rare alleles and FST (Index of genetic similarity M), using the only four polymorphic gene loci among 22 investigated (PGI-B, PGM-A, MNR-A and IDH-A). The geographic variation analysiswas based on Pearson 's correlations between four geographic and 14 genetic variables. Sorne evidence of isolation by distance and a weak gene flow among geographic regions was found. Patterns of elinal variation in relation to altitude (r = -0.62 for genetic diversity) and latitude (r = -0.77 for PGI-B3) were also observed, supporting the hypothesis of isolation by distance. No privatealleles were found at the single population level. Key words: Alnus acuminata, isozymes, gene flow, eline, geographic variation, Costa Rica, Panarna. Pollen and seed moverrient among counteract any potential for genetic drift subdivided popuIations in a tree speeies, (Hamrick 1992 in Boshieret al. -

Global Survey of Ex Situ Betulaceae Collections Global Survey of Ex Situ Betulaceae Collections

Global Survey of Ex situ Betulaceae Collections Global Survey of Ex situ Betulaceae Collections By Emily Beech, Kirsty Shaw and Meirion Jones June 2015 Recommended citation: Beech, E., Shaw, K., & Jones, M. 2015. Global Survey of Ex situ Betulaceae Collections. BGCI. Acknowledgements BGCI gratefully acknowledges the many botanic gardens around the world that have contributed data to this survey (a full list of contributing gardens is provided in Annex 2). BGCI would also like to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in the promotion of the survey and the collection of data, including the Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh, Yorkshire Arboretum, University of Liverpool Ness Botanic Gardens, and Stone Lane Gardens & Arboretum (U.K.), and the Morton Arboretum (U.S.A). We would also like to thank contributors to The Red List of Betulaceae, which was a precursor to this ex situ survey. BOTANIC GARDENS CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL (BGCI) BGCI is a membership organization linking botanic gardens is over 100 countries in a shared commitment to biodiversity conservation, sustainable use and environmental education. BGCI aims to mobilize botanic gardens and work with partners to secure plant diversity for the well-being of people and the planet. BGCI provides the Secretariat for the IUCN/SSC Global Tree Specialist Group. www.bgci.org FAUNA & FLORA INTERNATIONAL (FFI) FFI, founded in 1903 and the world’s oldest international conservation organization, acts to conserve threatened species and ecosystems worldwide, choosing solutions that are sustainable, based on sound science and take account of human needs. www.fauna-flora.org GLOBAL TREES CAMPAIGN (GTC) GTC is undertaken through a partnership between BGCI and FFI, working with a wide range of other organisations around the world, to save the world’s most threated trees and the habitats which they grow through the provision of information, delivery of conservation action and support for sustainable use. -

Epiphyte Diversity and Biomass Loads of Canopy Emergent Trees in Chilean Temperate Rain Forests: a Neglected Functional Component

Forest Ecology and Management 259 (2010) 1490–1501 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forest Ecology and Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foreco Epiphyte diversity and biomass loads of canopy emergent trees in Chilean temperate rain forests: A neglected functional component Iva´nA.Dı´az a,b,c,*, Kathryn E. Sieving b, Maurice E. Pen˜a-Foxon c, Juan Larraı´n d, Juan J. Armesto c,e a Instituto de Silvicultura, Facultad de Ciencias Forestales y Recursos Naturales, Universidad Austral de Chile, P.O. Box 567, Valdivia, Chile b Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL USA c Institute of Ecology and Biodiversity IEB, Las Palmeras 3425, N˜un˜oa, Santiago, Chile d Departamento de Bota´nica, Universidad de Concepcio´n, Concepcio´n, Chile e Center for Advanced Studies in Ecology and Biodiversity, Departamento de Ecologı´a, Pontificia Universidad Cato´lica de Chile, Santiago, Chile ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: We document for the first time the epiphytic composition and biomass of canopy emergent trees from Received 11 August 2009 temperate, old-growth coastal rainforests of Chile (428300S). Through tree-climbing techniques, we Received in revised form 13 January 2010 accessed the crown of two large (c. 1 m trunk diameter, 25–30 m tall) individuals of Eucryphia cordifolia Accepted 14 January 2010 (Cunoniaceae) and one large Aextoxicon punctatum (Aextoxicaceae) to sample all epiphytes from the base to the treetop. Epiphytes, with the exception of the hemi-epiphytic tree Raukaua laetevirens (Araliaceae), Keywords: were removed, weighed and subsamples dried to estimate total dry mass. We recorded 22 species of Epiphytes vascular epiphytes, and 22 genera of cryptogams, with at least 30 species of bryophytes, liverworts and Emergent canopy trees lichens. -

Supporting Information

Supporting Information Mao et al. 10.1073/pnas.1114319109 SI Text BEAST Analyses. In addition to a BEAST analysis that used uniform Selection of Fossil Taxa and Their Phylogenetic Positions. The in- prior distributions for all calibrations (run 1; 144-taxon dataset, tegration of fossil calibrations is the most critical step in molecular calibrations as in Table S4), we performed eight additional dating (1, 2). We only used the fossil taxa with ovulate cones that analyses to explore factors affecting estimates of divergence could be assigned unambiguously to the extant groups (Table S4). time (Fig. S3). The exact phylogenetic position of fossils used to calibrate the First, to test the effect of calibration point P, which is close to molecular clocks was determined using the total-evidence analy- the root node and is the only functional hard maximum constraint ses (following refs. 3−5). Cordaixylon iowensis was not included in in BEAST runs using uniform priors, we carried out three runs the analyses because its assignment to the crown Acrogymno- with calibrations A through O (Table S4), and calibration P set to spermae already is supported by previous cladistic analyses (also [306.2, 351.7] (run 2), [306.2, 336.5] (run 3), and [306.2, 321.4] using the total-evidence approach) (6). Two data matrices were (run 4). The age estimates obtained in runs 2, 3, and 4 largely compiled. Matrix A comprised Ginkgo biloba, 12 living repre- overlapped with those from run 1 (Fig. S3). Second, we carried out two runs with different subsets of sentatives from each conifer family, and three fossils taxa related fi to Pinaceae and Araucariaceae (16 taxa in total; Fig. -

Ancistrocladaceae

Soltis et al—American Journal of Botany 98(4):704-730. 2011. – Data Supplement S2 – page 1 Soltis, Douglas E., Stephen A. Smith, Nico Cellinese, Kenneth J. Wurdack, David C. Tank, Samuel F. Brockington, Nancy F. Refulio-Rodriguez, Jay B. Walker, Michael J. Moore, Barbara S. Carlsward, Charles D. Bell, Maribeth Latvis, Sunny Crawley, Chelsea Black, Diaga Diouf, Zhenxiang Xi, Catherine A. Rushworth, Matthew A. Gitzendanner, Kenneth J. Sytsma, Yin-Long Qiu, Khidir W. Hilu, Charles C. Davis, Michael J. Sanderson, Reed S. Beaman, Richard G. Olmstead, Walter S. Judd, Michael J. Donoghue, and Pamela S. Soltis. Angiosperm phylogeny: 17 genes, 640 taxa. American Journal of Botany 98(4): 704-730. Appendix S2. The maximum likelihood majority-rule consensus from the 17-gene analysis shown as a phylogram with mtDNA included for Polyosma. Names of the orders and families follow APG III (2009); other names follow Cantino et al. (2007). Numbers above branches are bootstrap percentages. 67 Acalypha Spathiostemon 100 Ricinus 97 100 Dalechampia Lasiocroton 100 100 Conceveiba Homalanthus 96 Hura Euphorbia 88 Pimelodendron 100 Trigonostemon Euphorbiaceae Codiaeum (incl. Peraceae) 100 Croton Hevea Manihot 10083 Moultonianthus Suregada 98 81 Tetrorchidium Omphalea 100 Endospermum Neoscortechinia 100 98 Pera Clutia Pogonophora 99 Cespedesia Sauvagesia 99 Luxemburgia Ochna Ochnaceae 100 100 53 Quiina Touroulia Medusagyne Caryocar Caryocaraceae 100 Chrysobalanus 100 Atuna Chrysobalananaceae 100 100 Licania Hirtella 100 Euphronia Euphroniaceae 100 Dichapetalum 100