Vol 24 Issue 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sab 2012 Mecbpn

Dos-Santos,W.A., et al. PROPOSTA DE UMA MISSÃO ESPACIAL PARA PICOSATÉLITES E ... PROPOSTA DE UMA MISSÃO ESPACIAL COMPLETA PARA PICOSATÉLITES E NANOSATÉLITES UTILIZANDO LANÇADORES NACIONAIS Walter Abrahão dos Santos, Fernanda Sayuri Yamasaki, Wilson Yamaguti Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais – Av. dos Astronautas,1758 - CP515 - CEP 12227-010 São José dos Campos - SP, [email protected] , [email protected] , [email protected] Flávio de Azevedo Corrêa Jr. Instituto de Aeronáutica e Espaço – DCTA/IAE/SESP/PE, Praça Mal. Eduardo Gomes, 50 - Vila das Acácias, 12.228-904 - São José dos Campos - SP - Brasil - [email protected] Resumo: Devido ao mercado emergente de aplicações para pico e nanosatélites nas áreas de Espaço e Defesa, este trabalho se inspira na Missão Espacial Completa Brasileira (MECB), um programa conjunto de satélites e lançadores brasileiros, para propor um programa indutor de lançadores e plataformas voltados para satélites miniaturizados com missões sofisticadas devido a avanços em nanotecnologia e computação, entre outros. O trabalho considera dois grandes segmentos: (1) o segmento de lançadores focado na análise de viabilidade de veículos lançadores de pequenas cargas a uma altitude de aproximadamente 300 km e (2) o segmento relativo aos satélites objetivando embarcar cargas úteis com as seguintes aplicações em vista: um radiômetro, uma microcâmera e formação em voo. A análise foi basicamente concentrada nos envelopes de massa, tamanho, potência. A sustentabilidade do programa para estes satélites requer um acesso barato e regular ao espaço e é atrativa pela projeção futura deste nicho de mercado que pode contribuir com objetivos estratégicos do país. -

Paris Commune Imagery in China's Mass Media

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 128 852 CS 202 971 AUTHOR Meiss, Guy T. TITLE Paris Commune Imagery in China's mass Media. PUB DATE 76 NOT: 38p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism (59th, College Park, Maryland, July 31-August 4, 1976) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$2.06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Imagery; *Information Dissemination; Journalism; *Mass Media; Persuasive Discourse; Political Influences; *Political Socialization; *Propaganda; Rhetorical Criticism IDENTIFIERS China; Paris Commune; Shanghai Peoples Commune ABSTRACT The role of ideology in mass media practices is explored in an analysis of the relation between theParis Commune of 1871 and the Shanghai Commune of 1967, two attempts totranslate the -philosophical concept of dictatorship of the proletariatinto some political form. A review of the use of Paris Commune imagery bythe Chinese to mobilize the population for politicaldevelopment highlights the critical role of ideology in understanding the operation of the mass media and the difficulties theChinese have in continuing their revolution in the political andbureaucratic superstructure. (Author/AA) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include manyinformal unpublished * materials not available from other sources.ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available.Nevertheless, items of marginal * * reproducibility are often encounteredand this affects the quality * * of the microfiche and hardcopyreproductions ERIC makes -

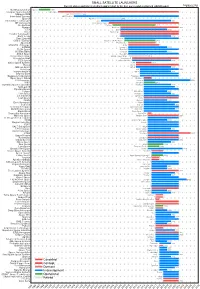

Small Satellite Launchers

SMALL SATELLITE LAUNCHERS NewSpace Index 2020/04/20 Current status and time from development start to the first successful or planned orbital launch NEWSPACE.IM Northrop Grumman Pegasus 1990 Scorpius Space Launch Demi-Sprite ? Makeyev OKB Shtil 1998 Interorbital Systems NEPTUNE N1 ? SpaceX Falcon 1e 2008 Interstellar Technologies Zero 2021 MT Aerospace MTA, WARR, Daneo ? Rocket Lab Electron 2017 Nammo North Star 2020 CTA VLM 2020 Acrux Montenegro ? Frontier Astronautics ? ? Earth to Sky ? 2021 Zero 2 Infinity Bloostar ? CASIC / ExPace Kuaizhou-1A (Fei Tian 1) 2017 SpaceLS Prometheus-1 ? MISHAAL Aerospace M-OV ? CONAE Tronador II 2020 TLON Space Aventura I ? Rocketcrafters Intrepid-1 2020 ARCA Space Haas 2CA ? Aerojet Rocketdyne SPARK / Super Strypi 2015 Generation Orbit GoLauncher 2 ? PLD Space Miura 5 (Arion 2) 2021 Swiss Space Systems SOAR 2018 Heliaq ALV-2 ? Gilmour Space Eris-S 2021 Roketsan UFS 2023 Independence-X DNLV 2021 Beyond Earth ? ? Bagaveev Corporation Bagaveev ? Open Space Orbital Neutrino I ? LIA Aerospace Procyon 2026 JAXA SS-520-4 2017 Swedish Space Corporation Rainbow 2021 SpinLaunch ? 2022 Pipeline2Space ? ? Perigee Blue Whale 2020 Link Space New Line 1 2021 Lin Industrial Taymyr-1A ? Leaf Space Primo ? Firefly 2020 Exos Aerospace Jaguar ? Cubecab Cab-3A 2022 Celestia Aerospace Space Arrow CM ? bluShift Aerospace Red Dwarf 2022 Black Arrow Black Arrow 2 ? Tranquility Aerospace Devon Two ? Masterra Space MINSAT-2000 2021 LEO Launcher & Logistics ? ? ISRO SSLV (PSLV Light) 2020 Wagner Industries Konshu ? VSAT ? ? VALT -

Redalyc.Status and Trends of Smallsats and Their Launch Vehicles

Journal of Aerospace Technology and Management ISSN: 1984-9648 [email protected] Instituto de Aeronáutica e Espaço Brasil Wekerle, Timo; Bezerra Pessoa Filho, José; Vergueiro Loures da Costa, Luís Eduardo; Gonzaga Trabasso, Luís Status and Trends of Smallsats and Their Launch Vehicles — An Up-to-date Review Journal of Aerospace Technology and Management, vol. 9, núm. 3, julio-septiembre, 2017, pp. 269-286 Instituto de Aeronáutica e Espaço São Paulo, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=309452133001 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative doi: 10.5028/jatm.v9i3.853 Status and Trends of Smallsats and Their Launch Vehicles — An Up-to-date Review Timo Wekerle1, José Bezerra Pessoa Filho2, Luís Eduardo Vergueiro Loures da Costa1, Luís Gonzaga Trabasso1 ABSTRACT: This paper presents an analysis of the scenario of small satellites and its correspondent launch vehicles. The INTRODUCTION miniaturization of electronics, together with reliability and performance increase as well as reduction of cost, have During the past 30 years, electronic devices have experienced allowed the use of commercials-off-the-shelf in the space industry, fostering the Smallsat use. An analysis of the enormous advancements in terms of performance, reliability and launched Smallsats during the last 20 years is accomplished lower prices. In the mid-80s, a USD 36 million supercomputer and the main factors for the Smallsat (r)evolution, outlined. -

Chapter 1 the Meaning of Detente

Notes CHAPTER 1 THE MEANING OF DETENTE I. Arthur M. Schlesinger,Jr., 'Detente: an American Perspective', in Detente in Historical Perspective, edited by G. Schwab and H. Friedlander (NY: Ciro Press, 1975) p. 125. From Hamlet, Act III, Scene 2. 2. Gustav Pollak Lecture at Harvard, 14 April 1976; reprinted in James Schlesinger, 'The Evolution of American Policy Towards the Soviet Union', International Security; Summer 1976, vol. I, no. I, pp. 46-7 . 3. Theodore Draper, 'Appeasement and Detente', Commentary, Feb . 1976, vol. 61, no. 8, p. 32. 4. Coral Bell, in her book, TheDiplomacy ofDitente (London: Martin Robertson, 1977), has written an extensive analysis of the triangular relationship but points out that, as of yet, no third side to the triangle - the detente between China and the USSR - exists, p. 5. 5. Seyom Brown, 'A Cooling-Off Period for U.S.-Soviet Relations', Foreign Policy , Fall 1977, no. 28, p. 12. See also 1. Aleksandrov, 'Peking: a Course Aimed at Disrupting International Detente Under Cover of Anti Sovietism', Pravda , 14 May 1977- translated in Current DigestofSovietPress . Hereafter, only the Soviet publication will be named. 6. Vladimir Petrov , U.S.-Soviet Detente: Past and Future (Wash ington D.C .: American Enterprise Institute for Publi c Policy Research, 1975) p. 2. 7. N. Kapcheko, 'Socialist Foreign Policy and the Reconstruction of Inter national Relations', International Affairs (Moscow), no. 4, Apr . 1975, p. 8. 8. L. Brezhnev, Report ofthe Tioenty-Fiftn Congress ofthe Communist Parry ofthe Soviet Union, 24 Feb. 1976. 9. Marshall Shulman, 'Toward a Western Philosophy of Coexistence',Foreign Affairs, vol. -

By KLAUS MEHNERT the Beautiful Hawaiian Word "'Aloha

.. By KLAUS MEHNERT Va mall. k6 fla 0 ka aina i ka pono. (The life of the la~ is preserved by righteousness.) Motto of Hawaii. The beautiful Hawaiian word like this. If, for instance, a person "'Aloha" cannot be translated. It says, "1 am now leaving Germany," means love, friendship, sympathy, it really does not mean very much. He farewell, and much more. The follow is perhaps looking at a railway station ing lines are an Aloha in two ways. on the Belgian border, or at the banks They are a friendly farewell to the hos of the lower Elbe, or possibly at the pitable islands on which I lived for mountains of the Brenner Pass, and four years, and they are also a good each time he sees only an infinitesimal bye to old Hawaii, which toward the fragment of Germany. Germany itself dosure of my sta:Jh-,was undergoing a is much more, ( ...;k nOPQdy has ever rapid transformation. and which, if seen i~ a whole. But here the entire this development shou.ld continue, will island 11e; before me. From the light disappear. never to return. house on Barber's Point to the crater Hawaii's transformation from a of Koko Head I can see every ridge of south sea paradise to a naval and the two parallel volcanic mountain military fortress of first magnitude ranges and the broad valley lying be 'seems inevitable. The time may soon tween them, filled with sugar cane and come. when people, who no'tl':rassociate pineapple fields. In the fiery sunset the name of Hawaii with rt·1Jt~·girls the mountains and valleys are indescrib and palm trees in the moonlignt, will ably green and seem very near as the link the islands with nothing but coast deep shadows accentuate every line. -

A Brazilian Space Launch System for the Small Satellite Market

aerospace Article A Brazilian Space Launch System for the Small Satellite Market Pedro L. K. da Cás 1 , Carlos A. G. Veras 2,* , Olexiy Shynkarenko 1 and Rodrigo Leonardi 3 1 Chemical Propulsion Laboratory, University of Brasília, Brasília 70910-900, DF, Brazil; [email protected] (P.L.K.d.C.); [email protected] (O.S.) 2 Mechanical Engineering Department, University of Brasília, Brasília 70910-900, DF, Brazil 3 Directorate of Satellites, Applications and Development, Brazilian Space Agency, Brasília 70610-200, DF, Brazil; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 8 July 2019; Accepted: 8 October 2019; Published: 12 November 2019 Abstract: At present, most small satellites are delivered as hosted payloads on large launch vehicles. Considering the current technological development, constellations of small satellites can provide a broad range of services operating at designated orbits. To achieve that, small satellite customers are seeking cost-effective launch services for dedicated missions. This paper deals with performance and cost assessments of a set of launch vehicle concepts based on a solid propellant rocket engine (S-50) under development by the Institute of Aeronautics and Space (Brazil) with support from the Brazilian Space Agency. Cost estimation analysis, based on the TRANSCOST model, was carried out taking into account the costs of launch system development, vehicle fabrication, direct and indirect operation cost. A cost-competitive expendable launch system was identified by using three S-50 solid rocket motors for the first stage, one S-50 engine for the second stage and a flight-proven cluster of pressure-fed liquid engines for the third stage. -

Challenges of the Brazilian National Space Law and Policy

United Nations/Brazil Symposium on Basic Space Technology Creating Novel Opportunities with Small Satellite Space Missions 11-14 September 2018, Natal-RN, Brazil Small Satellites: Challenges of the Brazilian National Space Law and Policy Ms. Ana Cristina Galhego Rosa Founder & CEO at Dipteron UG United Dr. Himilcon de C. Carvalho, Nations/Brazil COO at Visiona – Space Technology Symposium on Basic Space Technology “Creating Novel "I was born and raised in the middle of the war. I saw violence and a lot of people dying. I was afraid, very afraid. I did not want to see hate ever again. What I want is that the humanity live in peace“ - Vietnamese broadcast on Castro's satellite. Voice message from children around the world who asked for peace between nations. Júnior Torres de Castro (1933-2018), a Brazilian engineer who, using own resources, build the first Brazilian satellite for educational and humanitarian Oscar-Dove17 purposes that was launched in 1990. He was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. He was the first and (so far) the only private person to launch a satellite. OUTLINE • Brazilian Small Satellite Program • Legal Framework Overview • Policy Framework: The Brazilian National Plan For Space Activities (PNAE 2012 – 2021) • The Provisional Draft of the Brazilian National Legislation for Space Activities - a Non- Governmental Initiative • Recommendations for establishing a National Space Legislation • Recommendations for establishing a Brazilian National Policy for Small Satellite Brazilian Small Satellite Program Begining 1993-1997: -

Annex 7. Orbit Modelling and Analysis, Simulated Mission Planning

30th June 2013 SAR Formation Flying Annex 7. Orbit Modelling and Analysis, Simulated Mission Planning Document Version: V01_00 Dr Li Qiao Australian Centre for Space Engineering Research (ACSER) University of New South Wales, Sydney, 2052, Australia Revision History Version No. Date Author Description of Change V01_00 30th June 2013 Dr Li Qiao Initial Release TABLE OF CONTENT 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................... 8 2. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 10 3. MISSION APPLICATION REQUIREMENTS....................................................................................... 12 3.1. Soil Moisture Monitoring of Murray Darling Basin (MDB) ................................................... 12 3.2. Power System Requirements ................................................................................................ 12 3.3. Orbit Lifetime ........................................................................................................................ 12 4. ORBIT SELECTION FOR GARADA.................................................................................................... 14 4.1. Orbit Definition ..................................................................................................................... 14 4.2. Orbit Type ............................................................................................................................ -

The Life and Works of Zhang Ailing

THE LIFE AND WORKS OF ZHANG AILING: A CRITICAL STUDY by CAROLE H. F. HOYAN B. A. (Hons.), The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 1990 M. Phil., The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 1992 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FUIJFJ1LMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Asian Studies We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA August 1996 © Carole H. F. Hoyan, 1996 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University . of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission .for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of _/<- 'a. The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date 3» /\/,rv. (f<lA Abstract This dissertation is a study of Zhang Ailing's life and works and aims to provide a comprehensive overview of her literary career. Zhang Ailing (Eileen Chang %. jf; 5£% 1920-1995) is a significant figure in modern Chinese literary history, not only because of her outstanding artistry and modernist vision, but also because of her diverse contributions to the course of Chinese literature. The study follows the conventional chronological order of her life and is divided into eight chapters, together with an introduction and a conclusion. -

Curriculum Vitae Sören Urbansky

Curriculum vitae Sören Urbansky Education and Degrees 18/2/2014 Dr. phil. in History, University of Konstanz (summa cum laude) Title of dissertation: “Beyond the Steppe Hill: The Making of the Sino- Russian border” Academic advisors: Jürgen Osterhammel and Karl Schlögel 20/10/2006 Diploma in History and Cultural Studies, European University Viadrina Frankfurt/Oder (1,1) 01/7/2000 Abitur, Ernst-Barlach-Gymnasium Kiel (1,7) Visiting studies at Tsinghua University Beijing (9/2006–7/2007); University of California, Berkeley (8/2005–5/2006); Heilongjiang University Harbin (9/2004–6/2005); Kazan’ State University (2/2003– 7/2003) Employment 1/2021–present Head of Office and Research Fellow in Global and Transnational History, Pacific Regional Office of the German Historical Institute Washington at the University of California, Berkeley 1/2018–12/2020 Research Fellow in Global and Transnational History, German Historical Institute Washington, DC 10/2016–12/2017 Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Social Anthropology, University of Cambridge, Darwin College Postdoctoral Research Affiliate (10/2016– 12/2016 on paternity leave) 4/2014–12/2017 Senior Lecturer (Akademischer Rat auf Zeit) of Russian and Asian Studies at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich 10/2009–3/2014 Lecturer (Wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter) of East Asian History at the University of Freiburg (11/2013–1/2014 on paternity leave) Visiting appointments and Membership in research groups 1/2021–present Visiting Professor, History Department, Central European University, Vienna -

Reinventing Space Conference 2018

Journal of the British Interplanetary Society VOLUME 71 NO.11 NOVEMBER 2018 Reinventing Space Conference 2018 THE MARKET FOR A UK LAUNCHER Vadim Zakirov et al THE REMOVEDEBRIS SPACE HARPOON Alexander Hall RAPID CONSTELLATION DEPLOYMENT from the UK Christopher Loghry & Marissa Stender REDESIGN & SPACE QUALIFICATION OF A 3D-PRINTED SATELLITE STRUCTURE with Polietherimide Jonathan Becedas et al THE EPSILON LAUNCH VEHICLE: Status and Future Ryoma Yamashiro & Imoto Takayuki THE NORMS OF BEHAVIOUR IN SPACE: Our space – Whose rules? Lesley Jane Smith www.bis-space.com ISSN 0007-084X PUBLICATION DATE: 31 JANUARY 2019 Submitting papers International Advisory Board to JBIS JBIS welcomes the submission of technical Rachel Armstrong, Newcastle University, UK papers for publication dealing with technical Peter Bainum, Howard University, USA reviews, research, technology and engineering in astronautics and related fields. Stephen Baxter, Science & Science Fiction Writer, UK James Benford, Microwave Sciences, California, USA Text should be: James Biggs, The University of Strathclyde, UK ■ As concise as the content allows – typically 5,000 to 6,000 words. Shorter papers (Technical Notes) Anu Bowman, Foundation for Enterprise Development, California, USA will also be considered; longer papers will only Gerald Cleaver, Baylor University, USA be considered in exceptional circumstances – for Charles Cockell, University of Edinburgh, UK example, in the case of a major subject review. Ian A. Crawford, Birkbeck College London, UK ■ Source references should be inserted in the text in square brackets – [1] – and then listed at the Adam Crowl, Icarus Interstellar, Australia end of the paper. Eric W. Davis, Institute for Advanced Studies at Austin, USA ■ Illustration references should be cited in Kathryn Denning, York University, Toronto, Canada numerical order in the text; those not cited in the Martyn Fogg, Probability Research Group, UK text risk omission.