Transcriptomic Analysis of the Effects of Toll-Like Receptor 4 and Its Ligands on the Gene Expression Network of Hepatic Stellate Cells Ouyang Et Al

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplemental Information to Mammadova-Bach Et Al., “Laminin Α1 Orchestrates VEGFA Functions in the Ecosystem of Colorectal Carcinogenesis”

Supplemental information to Mammadova-Bach et al., “Laminin α1 orchestrates VEGFA functions in the ecosystem of colorectal carcinogenesis” Supplemental material and methods Cloning of the villin-LMα1 vector The plasmid pBS-villin-promoter containing the 3.5 Kb of the murine villin promoter, the first non coding exon, 5.5 kb of the first intron and 15 nucleotides of the second villin exon, was generated by S. Robine (Institut Curie, Paris, France). The EcoRI site in the multi cloning site was destroyed by fill in ligation with T4 polymerase according to the manufacturer`s instructions (New England Biolabs, Ozyme, Saint Quentin en Yvelines, France). Site directed mutagenesis (GeneEditor in vitro Site-Directed Mutagenesis system, Promega, Charbonnières-les-Bains, France) was then used to introduce a BsiWI site before the start codon of the villin coding sequence using the 5’ phosphorylated primer: 5’CCTTCTCCTCTAGGCTCGCGTACGATGACGTCGGACTTGCGG3’. A double strand annealed oligonucleotide, 5’GGCCGGACGCGTGAATTCGTCGACGC3’ and 5’GGCCGCGTCGACGAATTCACGC GTCC3’ containing restriction site for MluI, EcoRI and SalI were inserted in the NotI site (present in the multi cloning site), generating the plasmid pBS-villin-promoter-MES. The SV40 polyA region of the pEGFP plasmid (Clontech, Ozyme, Saint Quentin Yvelines, France) was amplified by PCR using primers 5’GGCGCCTCTAGATCATAATCAGCCATA3’ and 5’GGCGCCCTTAAGATACATTGATGAGTT3’ before subcloning into the pGEMTeasy vector (Promega, Charbonnières-les-Bains, France). After EcoRI digestion, the SV40 polyA fragment was purified with the NucleoSpin Extract II kit (Machery-Nagel, Hoerdt, France) and then subcloned into the EcoRI site of the plasmid pBS-villin-promoter-MES. Site directed mutagenesis was used to introduce a BsiWI site (5’ phosphorylated AGCGCAGGGAGCGGCGGCCGTACGATGCGCGGCAGCGGCACG3’) before the initiation codon and a MluI site (5’ phosphorylated 1 CCCGGGCCTGAGCCCTAAACGCGTGCCAGCCTCTGCCCTTGG3’) after the stop codon in the full length cDNA coding for the mouse LMα1 in the pCIS vector (kindly provided by P. -

Tumour-Agnostic Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer and Biliary Tract Cancer

diagnostics Review Tumour-Agnostic Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer and Biliary Tract Cancer Shunsuke Kato Department of Clinical Oncology, Juntendo University Graduate School of Medicine, 2-1-1, Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8421, Japan; [email protected]; Tel.: +81-3-5802-1543 Abstract: The prognosis of patients with solid tumours has remarkably improved with the develop- ment of molecular-targeted drugs and immune checkpoint inhibitors. However, the improvements in the prognosis of pancreatic cancer and biliary tract cancer is delayed compared to other carcinomas, and the 5-year survival rates of distal-stage disease are approximately 10 and 20%, respectively. How- ever, a comprehensive analysis of tumour cells using The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project has led to the identification of various driver mutations. Evidently, few mutations exist across organs, and basket trials targeting driver mutations regardless of the primary organ are being actively conducted. Such basket trials not only focus on the gate keeper-type oncogene mutations, such as HER2 and BRAF, but also focus on the caretaker-type tumour suppressor genes, such as BRCA1/2, mismatch repair-related genes, which cause hereditary cancer syndrome. As oncogene panel testing is a vital approach in routine practice, clinicians should devise a strategy for improved understanding of the cancer genome. Here, the gene mutation profiles of pancreatic cancer and biliary tract cancer have been outlined and the current status of tumour-agnostic therapy in these cancers has been reported. Keywords: pancreatic cancer; biliary tract cancer; targeted therapy; solid tumours; driver mutations; agonist therapy Citation: Kato, S. Tumour-Agnostic Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer and 1. -

WO 2019/079361 Al 25 April 2019 (25.04.2019) W 1P O PCT

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization I International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2019/079361 Al 25 April 2019 (25.04.2019) W 1P O PCT (51) International Patent Classification: CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DJ, DK, DM, DO, C12Q 1/68 (2018.01) A61P 31/18 (2006.01) DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, C12Q 1/70 (2006.01) HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JO, JP, KE, KG, KH, KN, KP, KR, KW, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, (21) International Application Number: MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, PCT/US2018/056167 OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, (22) International Filing Date: SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, 16 October 2018 (16. 10.2018) TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (25) Filing Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (26) Publication Language: English GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, ST, SZ, TZ, (30) Priority Data: UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, 62/573,025 16 October 2017 (16. 10.2017) US TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, ΓΕ , IS, IT, LT, LU, LV, (71) Applicant: MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF MC, MK, MT, NL, NO, PL, PT, RO, RS, SE, SI, SK, SM, TECHNOLOGY [US/US]; 77 Massachusetts Avenue, TR), OAPI (BF, BJ, CF, CG, CI, CM, GA, GN, GQ, GW, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 (US). -

Supplementary Table 1. Pain and PTSS Associated Genes (N = 604

Supplementary Table 1. Pain and PTSS associated genes (n = 604) compiled from three established pain gene databases (PainNetworks,[61] Algynomics,[52] and PainGenes[42]) and one PTSS gene database (PTSDgene[88]). These genes were used in in silico analyses aimed at identifying miRNA that are predicted to preferentially target this list genes vs. a random set of genes (of the same length). ABCC4 ACE2 ACHE ACPP ACSL1 ADAM11 ADAMTS5 ADCY5 ADCYAP1 ADCYAP1R1 ADM ADORA2A ADORA2B ADRA1A ADRA1B ADRA1D ADRA2A ADRA2C ADRB1 ADRB2 ADRB3 ADRBK1 ADRBK2 AGTR2 ALOX12 ANO1 ANO3 APOE APP AQP1 AQP4 ARL5B ARRB1 ARRB2 ASIC1 ASIC2 ATF1 ATF3 ATF6B ATP1A1 ATP1B3 ATP2B1 ATP6V1A ATP6V1B2 ATP6V1G2 AVPR1A AVPR2 BACE1 BAMBI BDKRB2 BDNF BHLHE22 BTG2 CA8 CACNA1A CACNA1B CACNA1C CACNA1E CACNA1G CACNA1H CACNA2D1 CACNA2D2 CACNA2D3 CACNB3 CACNG2 CALB1 CALCRL CALM2 CAMK2A CAMK2B CAMK4 CAT CCK CCKAR CCKBR CCL2 CCL3 CCL4 CCR1 CCR7 CD274 CD38 CD4 CD40 CDH11 CDK5 CDK5R1 CDKN1A CHRM1 CHRM2 CHRM3 CHRM5 CHRNA5 CHRNA7 CHRNB2 CHRNB4 CHUK CLCN6 CLOCK CNGA3 CNR1 COL11A2 COL9A1 COMT COQ10A CPN1 CPS1 CREB1 CRH CRHBP CRHR1 CRHR2 CRIP2 CRYAA CSF2 CSF2RB CSK CSMD1 CSNK1A1 CSNK1E CTSB CTSS CX3CL1 CXCL5 CXCR3 CXCR4 CYBB CYP19A1 CYP2D6 CYP3A4 DAB1 DAO DBH DBI DICER1 DISC1 DLG2 DLG4 DPCR1 DPP4 DRD1 DRD2 DRD3 DRD4 DRGX DTNBP1 DUSP6 ECE2 EDN1 EDNRA EDNRB EFNB1 EFNB2 EGF EGFR EGR1 EGR3 ENPP2 EPB41L2 EPHB1 EPHB2 EPHB3 EPHB4 EPHB6 EPHX2 ERBB2 ERBB4 EREG ESR1 ESR2 ETV1 EZR F2R F2RL1 F2RL2 FAAH FAM19A4 FGF2 FKBP5 FLOT1 FMR1 FOS FOSB FOSL2 FOXN1 FRMPD4 FSTL1 FYN GABARAPL1 GABBR1 GABBR2 GABRA2 GABRA4 -

1714 Gene Comprehensive Cancer Panel Enriched for Clinically Actionable Genes with Additional Biologically Relevant Genes 400-500X Average Coverage on Tumor

xO GENE PANEL 1714 gene comprehensive cancer panel enriched for clinically actionable genes with additional biologically relevant genes 400-500x average coverage on tumor Genes A-C Genes D-F Genes G-I Genes J-L AATK ATAD2B BTG1 CDH7 CREM DACH1 EPHA1 FES G6PC3 HGF IL18RAP JADE1 LMO1 ABCA1 ATF1 BTG2 CDK1 CRHR1 DACH2 EPHA2 FEV G6PD HIF1A IL1R1 JAK1 LMO2 ABCB1 ATM BTG3 CDK10 CRK DAXX EPHA3 FGF1 GAB1 HIF1AN IL1R2 JAK2 LMO7 ABCB11 ATR BTK CDK11A CRKL DBH EPHA4 FGF10 GAB2 HIST1H1E IL1RAP JAK3 LMTK2 ABCB4 ATRX BTRC CDK11B CRLF2 DCC EPHA5 FGF11 GABPA HIST1H3B IL20RA JARID2 LMTK3 ABCC1 AURKA BUB1 CDK12 CRTC1 DCUN1D1 EPHA6 FGF12 GALNT12 HIST1H4E IL20RB JAZF1 LPHN2 ABCC2 AURKB BUB1B CDK13 CRTC2 DCUN1D2 EPHA7 FGF13 GATA1 HLA-A IL21R JMJD1C LPHN3 ABCG1 AURKC BUB3 CDK14 CRTC3 DDB2 EPHA8 FGF14 GATA2 HLA-B IL22RA1 JMJD4 LPP ABCG2 AXIN1 C11orf30 CDK15 CSF1 DDIT3 EPHB1 FGF16 GATA3 HLF IL22RA2 JMJD6 LRP1B ABI1 AXIN2 CACNA1C CDK16 CSF1R DDR1 EPHB2 FGF17 GATA5 HLTF IL23R JMJD7 LRP5 ABL1 AXL CACNA1S CDK17 CSF2RA DDR2 EPHB3 FGF18 GATA6 HMGA1 IL2RA JMJD8 LRP6 ABL2 B2M CACNB2 CDK18 CSF2RB DDX3X EPHB4 FGF19 GDNF HMGA2 IL2RB JUN LRRK2 ACE BABAM1 CADM2 CDK19 CSF3R DDX5 EPHB6 FGF2 GFI1 HMGCR IL2RG JUNB LSM1 ACSL6 BACH1 CALR CDK2 CSK DDX6 EPOR FGF20 GFI1B HNF1A IL3 JUND LTK ACTA2 BACH2 CAMTA1 CDK20 CSNK1D DEK ERBB2 FGF21 GFRA4 HNF1B IL3RA JUP LYL1 ACTC1 BAG4 CAPRIN2 CDK3 CSNK1E DHFR ERBB3 FGF22 GGCX HNRNPA3 IL4R KAT2A LYN ACVR1 BAI3 CARD10 CDK4 CTCF DHH ERBB4 FGF23 GHR HOXA10 IL5RA KAT2B LZTR1 ACVR1B BAP1 CARD11 CDK5 CTCFL DIAPH1 ERCC1 FGF3 GID4 HOXA11 IL6R KAT5 ACVR2A -

Molecular Mechanisms of the Antiangiogenic and Antitumor Effects of Mycophenolic Acid

1656 Molecular mechanisms of the antiangiogenic and antitumor effects of mycophenolic acid Sophie Domhan,1,2,3 Stefan Muschal,1 endothelial and fibroblast cells at 6 and 12 h after MPA Christian Schwager,1 Christian Morath,2 treatment. Network analysis revealed a critical role for Ute Wirkner,1 Wilhelm Ansorge,1 MYC signaling in endothelial cells treated with MPA. Christian Maercker,1 Martin Zeier,2 Moreover, we found that the antiangiogenic effects of MPA Peter E. Huber,1,3 and Amir Abdollahi1,3,4 were organized by coordinated communications between MYC and NDRG1, YYI, HIF1A, HDAC2, CDC2, GSK3B, and 1Department of Radiation Oncology, German Cancer Research PRKACB signaling. The regulation of these ‘‘hub nodes’’ Center, and 2Department of Nephrology, University of Heidelberg was confirmed by real-time quantitative reverse transcrip- 3 Medical School, Heidelberg, Germany and Center of Cancer tion-PCR and protein analysis. The critical involvement of Systems Biology, Department of Medicine, Caritas St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center, Tufts University School of Medicine; 4Children’s MYC in the antiangiogenic signaling of MPA was further Hospital Boston, Vascular Biology Program & Harvard Medical shown by gene knockdown experiments. Together, these School, Department of Surgery, Karp Family Research data provide a molecular basis for the antiangiogenic and Laboratories, Boston, Massachusetts antifibrotic effects of MPA, which warrants further clinical investigations. [Mol Cancer Ther 2008;7(6):1656–68] Abstract The relative risk for the development of malignancies Introduction following solid organ transplantation seems to be de- Mycophenolic acid (MPA) is a potent uncompetitive creased in patients treated with the immunosuppressive inhibitor of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase agent mycophenolic acid (MPA). -

Personalized Prediction of Acquired Resistance to EGFR-Targeted Inhibitors Using a Pathway-Based Machine Learning Approach

Cancers 2019, 11, x S1 of S9 Supplementary Materials: Personalized Prediction of Acquired Resistance to EGFR-Targeted Inhibitors Using a Pathway-Based Machine Learning Approach Young Rae Kim, Yong Wan Kim, Suh Eun Lee, Hye Won Yang and Sung Young Kim Table S1. Characteristics of individual studies. Sample Size Origin of Cancer Drug Dataset Platform S AR (Cell Lines) Lung cancer Agilent-014850 Whole Human GSE34228 26 26 (PC9) Genome Microarray 4x44K Gefitinib Epidermoid carcinoma Affymetrix Human Genome U133 GSE10696 3 3 (A431) Plus 2.0 Head and neck cancer Illumina HumanHT-12 V4.0 GSE62061 12 12 (Cal-27, SSC-25, FaDu, expression beadchip SQ20B) Erlotinib Head and neck cancer Illumina HumanHT-12 V4.0 GSE49135 3 3 (HN5) expression beadchip Lung cancer (HCC827, Illumina HumanHT-12 V3.0 GSE38310 3 6 ER3, T15-2) expression beadchip Lung cancer Illumina HumanHT-12 V3.0 GSE62504 1 2 (HCC827) expression beadchip Afatinib Lung cancer * Illumina HumanHT-12 V4.0 GSE75468 1 3 (HCC827) expression beadchip Head and neck cancer Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Cetuximab GSE21483 3 3 (SCC1) Plus 2.0 Array GEO, gene expression omnibus; GSE, gene expression series; S, sensitive; AR, acquired EGFR-TKI resistant; * Lung Cancer Cells Derived from Tumor Xenograft Model. Table S2. The performances of four penalized regression models. Model ACC precision recall F1 MCC AUROC BRIER Ridge 0.889 0.852 0.958 0.902 0.782 0.964 0.129 Lasso 0.944 0.957 0.938 0.947 0.889 0.991 0.042 Elastic Net 0.978 0.979 0.979 0.979 0.955 0.999 0.023 EPSGO Elastic Net 0.989 1.000 0.979 0.989 0.978 1.000 0.018 AUROC, area under curve of receiver operating characteristic; ACC, accuracy; MCC, Matthews correlation coefficient; EPSGO, Efficient Parameter Selection via Global Optimization algorithm. -

Chemical Agent and Antibodies B-Raf Inhibitor RAF265

Supplemental Materials and Methods: Chemical agent and antibodies B-Raf inhibitor RAF265 [5-(2-(5-(trifluromethyl)-1H-imidazol-2-yl)pyridin-4-yloxy)-N-(4-trifluoromethyl)phenyl-1-methyl-1H-benzp{D, }imidazol-2- amine] was kindly provided by Novartis Pharma AG and dissolved in solvent ethanol:propylene glycol:2.5% tween-80 (percentage 6:23:71) for oral delivery to mice by gavage. Antibodies to phospho-ERK1/2 Thr202/Tyr204(4370), phosphoMEK1/2(2338 and 9121)), phospho-cyclin D1(3300), cyclin D1 (2978), PLK1 (4513) BIM (2933), BAX (2772), BCL2 (2876) were from Cell Signaling Technology. Additional antibodies for phospho-ERK1,2 detection for western blot were from Promega (V803A), and Santa Cruz (E-Y, SC7383). Total ERK antibody for western blot analysis was K-23 from Santa Cruz (SC-94). Ki67 antibody (ab833) was from ABCAM, Mcl1 antibody (559027) was from BD Biosciences, Factor VIII antibody was from Dako (A082), CD31 antibody was from Dianova, (DIA310), and Cot antibody was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (sc-373677). For the cyclin D1 second antibody staining was with an Alexa Fluor 568 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, A10042) (1:200 dilution). The pMEK1 fluorescence was developed using the Alexa Fluor 488 chicken anti-rabbit IgG second antibody (1:200 dilution).TUNEL staining kits were from Promega (G2350). Mouse Implant Studies: Biopsy tissues were delivered to research laboratory in ice-cold Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) buffer solution. As the tissue mass available from each biopsy was limited, we first passaged the biopsy tissue in Balb/c nu/Foxn1 athymic nude mice (6-8 weeks of age and weighing 22-25g, purchased from Harlan Sprague Dawley, USA) to increase the volume of tumor for further implantation. -

Systems-Level Identification of PKA-Dependent Signaling In

Systems-level identification of PKA-dependent PNAS PLUS signaling in epithelial cells Kiyoshi Isobea, Hyun Jun Junga, Chin-Rang Yanga,J’Neka Claxtona, Pablo Sandovala, Maurice B. Burga, Viswanathan Raghurama, and Mark A. Kneppera,1 aEpithelial Systems Biology Laboratory, Systems Biology Center, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892-1603 Edited by Peter Agre, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, and approved August 29, 2017 (received for review June 1, 2017) Gproteinstimulatoryα-subunit (Gαs)-coupled heptahelical receptors targets are as yet unidentified. Some of the known PKA targets regulate cell processes largely through activation of protein kinase A are other protein kinases and phosphatases, meaning that PKA (PKA). To identify signaling processes downstream of PKA, we de- activation is likely to result in indirect changes in protein phos- leted both PKA catalytic subunits using CRISPR-Cas9, followed by a phorylation manifest as a signaling network, the details of which “multiomic” analysis in mouse kidney epithelial cells expressing the remain unresolved. To identify both direct and indirect targets of Gαs-coupled V2 vasopressin receptor. RNA-seq (sequencing)–based PKA in mammalian cells, we used CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing transcriptomics and SILAC (stable isotope labeling of amino acids in to introduce frame-shifting indel mutations in both PKA catalytic cell culture)-based quantitative proteomics revealed a complete loss subunit genes (Prkaca and Prkacb), thereby eliminating PKA-Cα of expression of the water-channel gene Aqp2 in PKA knockout cells. and PKA-Cβ proteins. This was followed by use of quantitative SILAC-based quantitative phosphoproteomics identified 229 PKA (SILAC-based) phosphoproteomics to identify phosphorylation phosphorylation sites. -

GPCR Signaling Inhibits Mtorc1 Via PKA Phosphorylation of Raptor

RESEARCH ARTICLE GPCR signaling inhibits mTORC1 via PKA phosphorylation of Raptor Jenna L Jewell1,2,3*, Vivian Fu4,5, Audrey W Hong4,5, Fa-Xing Yu6, Delong Meng1,2,3, Chase H Melick1,2,3, Huanyu Wang1,2,3, Wai-Ling Macrina Lam4,5, Hai-Xin Yuan4,5, Susan S Taylor4,7, Kun-Liang Guan4,5* 1Department of Molecular Biology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, United States; 2Harold C Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, United States; 3Hamon Center for Regenerative Science and Medicine, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, United States; 4Department of Pharmacology, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, United States; 5Moores Cancer Center, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, United States; 6Children’s Hospital and Institutes of Biomedical Sciences, Fudan University, Shanghai, China; 7Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, United States Abstract The mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) regulates cell growth, metabolism, and autophagy. Extensive research has focused on pathways that activate mTORC1 like growth factors and amino acids; however, much less is known about signaling cues that directly inhibit mTORC1 activity. Here, we report that G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) paired to Gas proteins increase cyclic adenosine 3’5’ monophosphate (cAMP) to activate protein kinase A (PKA) and inhibit mTORC1. Mechanistically, PKA phosphorylates the mTORC1 component Raptor on Ser 791, leading to decreased mTORC1 activity. Consistently, in cells where Raptor Ser 791 is mutated to Ala, mTORC1 activity is partially rescued even after PKA activation. Gas-coupled GPCRs *For correspondence: stimulation leads to inhibition of mTORC1 in multiple cell lines and mouse tissues. -

Fibrosis Accumulation in Idiopathic Pulmonary Apoptosis

Increased Cell Surface Fas Expression Is Necessary and Sufficient To Sensitize Lung Fibroblasts to Fas Ligation-Induced Apoptosis: Implications for Fibroblast This information is current as Accumulation in Idiopathic Pulmonary of October 1, 2021. Fibrosis Murry W. Wynes, Benjamin L. Edelman, Amanda G. Kostyk, Michael G. Edwards, Christopher Coldren, Steve D. Groshong, Gregory P. Cosgrove, Elizabeth F. Redente, Alison Bamberg, Kevin K. Brown, Nichole Reisdorph, Downloaded from Rebecca C. Keith, Stephen K. Frankel and David W. H. Riches J Immunol 2011; 187:527-537; Prepublished online 1 June 2011; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100447 http://www.jimmunol.org/ http://www.jimmunol.org/content/187/1/527 Supplementary http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2011/06/01/jimmunol.110044 Material 7.DC1 References This article cites 62 articles, 18 of which you can access for free at: by guest on October 1, 2021 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/187/1/527.full#ref-list-1 Why The JI? Submit online. • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2011 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. -

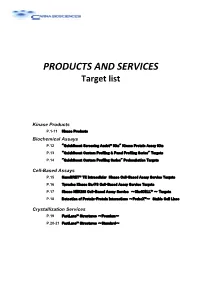

PRODUCTS and SERVICES Target List

PRODUCTS AND SERVICES Target list Kinase Products P.1-11 Kinase Products Biochemical Assays P.12 "QuickScout Screening Assist™ Kits" Kinase Protein Assay Kits P.13 "QuickScout Custom Profiling & Panel Profiling Series" Targets P.14 "QuickScout Custom Profiling Series" Preincubation Targets Cell-Based Assays P.15 NanoBRET™ TE Intracellular Kinase Cell-Based Assay Service Targets P.16 Tyrosine Kinase Ba/F3 Cell-Based Assay Service Targets P.17 Kinase HEK293 Cell-Based Assay Service ~ClariCELL™ ~ Targets P.18 Detection of Protein-Protein Interactions ~ProbeX™~ Stable Cell Lines Crystallization Services P.19 FastLane™ Structures ~Premium~ P.20-21 FastLane™ Structures ~Standard~ Kinase Products For details of products, please see "PRODUCTS AND SERVICES" on page 1~3. Tyrosine Kinases Note: Please contact us for availability or further information. Information may be changed without notice. Expression Protein Kinase Tag Carna Product Name Catalog No. Construct Sequence Accession Number Tag Location System HIS ABL(ABL1) 08-001 Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal His Insect (sf21) ABL(ABL1) BTN BTN-ABL(ABL1) 08-401-20N Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal DYKDDDDK Insect (sf21) ABL(ABL1) [E255K] HIS ABL(ABL1)[E255K] 08-094 Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal His Insect (sf21) HIS ABL(ABL1)[T315I] 08-093 Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal His Insect (sf21) ABL(ABL1) [T315I] BTN BTN-ABL(ABL1)[T315I] 08-493-20N Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal DYKDDDDK Insect (sf21) ACK(TNK2) GST ACK(TNK2) 08-196 Catalytic domain