TRANSACTION's of the MISSOURI ACAD.Emvi of SCIENCE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phylogeny of Psephenidae (Coleoptera: Byrrhoidea) Based on Larval, Pupal and Adult Characters

Systematic Entomology (2007), 32, 502–538 DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-3113.2006.00374.x Phylogeny of Psephenidae (Coleoptera: Byrrhoidea) based on larval, pupal and adult characters CHI-FENG LEE1 , MASATAKA SATOˆ2 , WILLIAM D. SHEPARD3 and M A N F R E D A . J A¨CH4 1Institute of Biodiversity, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan 701, Taiwan, 2Dia Cuore 306, Kamegahora 3-1404, Midoriku, Nagoya, 458-0804, Japan, 3Essig Museum of Entomology, 201 Wellman Hall, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, U.S.A., and 4Natural History Museum, Burgring 7, A-1010 Wien, Austria Abstract. We conducted the first comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of Pse- phenidae, based on 143 morphological characters of adults, larvae and pupae and coded for 34 taxa, representing three outgroups and 31 psephenid genera, including four undescribed ones. A strict consensus tree calculated (439 steps, consistency index ¼ 0.45, retention index ¼ 0.75) from the two most-parsimonious cladograms indicated that the monophyly of the family and subfamilies is supported, with the exception of Eubriinae, which is paraphyletic when including Afroeubria. Here a new subfamily, Afroeubriinae (subfam.n.), is formally estab- lished for Afroeubria. The analysis also indicated that the ‘streamlined’ larva is a derived adaptive radiation. Here, suprageneric taxonomy and the evolution of some significant characters are discussed. Keys are provided to the subfamilies and genera of Psephenidae considering larvae, adults and pupae. Introduction type specimens and the association of adults and immature stages by rearing, five new genera were proposed for Ori- Psephenidae, the ‘water penny’ beetles, are characterized by ental taxa and a well-resolved phylogenetic tree was ob- the peculiar larval body shape (Figs 4–7). -

FOOTBALL CROWD BEHAVIORAL RESPONSES to a UNIVERSITY MARCHING BAND's MUSICAL PROMPTS by AMANDA L. SMITH a THESIS Presented To

FOOTBALL CROWD BEHAVIORAL RESPONSES TO A UNIVERSITY MARCHING BAND’S MUSICAL PROMPTS by AMANDA L. SMITH A THESIS Presented to the School of Music and Dance and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music June 2018 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Amanda L. Smith Title: Football Crowd Behavioral Responses to a University Marching Band’s Musical Prompts This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Music degree in the School of Music and Dance by: Dr. Eric Wiltshire Chair Dr. Melissa Brunkan Member Dr. Beth Wheeler Member and Sara D. Hodges Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2018. ii © 2018 Amanda L. Smith iii THESIS ABSTRACT Amanda L. Smith Master of Music School of Music and Dance June 2018 Title: Football Crowd Behavioral Responses to a University Marching Band’s Musical Prompts Decades of market research have investigated how music can influence consumer purchase, food consumption, and alcoholic drinking. Before market researchers declared music an influencer of atmospheric perception, sociologists discovered the sway of music on crowd collective action in sporting events, political rallies, and societal unrest. There remains a lack of research on how live music may influence football fan behavior during a game. Therefore, this study observed the number of behavioral responses from university students elicited by a university marching band’s music prompts (N = 11) at an American university football game. -

Rare Aquatic Insects, Or How Valuable Are Bugs? Richard W

Great Basin Naturalist Memoirs Volume 3 The Endangered Species: A Symposium Article 8 12-1-1979 Rare aquatic insects, or how valuable are bugs? Richard W. Baumann Monte L. Bean Life Science Museum and Department of Zoology, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah 84602 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbnm Recommended Citation Baumann, Richard W. (1979) "Rare aquatic insects, or how valuable are bugs?," Great Basin Naturalist Memoirs: Vol. 3 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbnm/vol3/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist Memoirs by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. RARE AQUATIC INSECTS, OR HOW VALUABLE ARE BUGS? Richard W. Bauinann' Abstract.— Insects are an important element in the analysis of aquatic ecosystems, (1) because the limited dis- persal abilities of many aquatic species means that they must make a living under existing conditions, and (2) be- cause they are often sensitive to slight changes in water and stream quality, thus making excellent indicators of the physical and chemical conditions in a system. Examples of rare, ecologically sensitive species are presented from the Plecoptera, Ephemeroptera, and Trichoptera. Detailed studies of rare aquatic insect species should produce impor- tant information on critical habitats that will be useful in the protection of endangered and threatened species in other groups of animals and plants. I use the term rare instead of endangered the distribution patterns of certain species fit or threatened, because no aquatic insects are nicely with a model of island biogeography. -

T TA /Î-T Dissertation Ij L Y L I Information Service

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a manuscript sent to us for publication and microfilming. While the most advstnced technology has been used to pho tograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. Pages in any manuscript may have indistinct print. In all cases the best available copy has been filmed. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Manuscripts may not always be complete. When it is not possible to obtain missing pages, a note appears to indicate this. 2. When copyrighted materials are removed from the manuscript, a note ap pears to indicate this. 3. Oversize materials (maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sec tioning the original, beginning at the upper left hand comer and continu ing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is also filmed as one exposure and is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 35mm slide or in black and white paper format. * 4. Most photographs reproduce acceptably on positive microfilm or micro fiche but lack clarify on xerographic copies made from the microfilm. For an additional charge, all photographs are available in black and white standard 35mm slide format.* *For more information about black and white slides or enlarged paper reproductions, please contact the Dissertations Customer Services Department. T TA /Î-T Dissertation i J l Y l i Information Service University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 N. -

The Art of Empathy Translation.Pdf

共感の芸術 • Sztuka empatii • L’art de l’empathie • Изкуството на емпатия • Empati Sanat • 同情的藝術 • A Arta de empatie • Nghệ thuật của đồng • هبئاش یب یدردمه زا رنه • művészet, az empátia • Уметност емпатије -Arti i Empatia • Sanaa ya uelewa • Umjetnost em • فطاعتلا نف • cảm • Taiteen empatiaa • Ubuciko Uzwela patije • 공감의 예술 • Umění empatie • L’arte di empatia • Η τέχνη της ενσυναίσθησης • Kunsten å empati • El arte de la empatía • ang sining ng makiramay • یلدمه رنه • Die Kunst der Empathie • A arte da empatia • National Endowment for the Arts Искусство сопереживания • 共感の芸術 • Sztuka empatii • L’art de l’empathie • Изкуството на емпатия • -Arta de em • هبئاش یب یدردمه زا رنه • Empati Sanat • 同情的藝術 • A művészet, az empátia • Уметност емпатије Arti i Empatia • Sanaa ya • فطاعتلا نف • patie • Nghệ thuật của đồng cảm • Taiteen empatiaa • Ubuciko Uzwela uelewa • Umjetnost empatije • 공감의 예술 • Umění empatie • L’arte di empatia • Η τέχνη της ενσυναίσθησης El arte de la empatía • ang sining • یلدمه رنه • Kunsten å empati • Die Kunst der Empathie • A arte da empatia • ng makiramay • Искусство сопереживания • 共感の芸術 • Sztuka empatii • L’art de l’empathie • Изкуството هبئاش یب یدردمه زا رنه • на емпатия • Empati Sanat • 同情的藝術 • A művészet, az empátia • Уметност емпатије -Arti i Em • فطاعتلا نف • Arta de empatie • Nghệ thuật của đồng cảm • Taiteen empatiaa • Ubuciko Uzwela • patia • Sanaa ya uelewa • Umjetnost empatije • 공감의 예술 • Umění empatie • L’arte di empatia • Η τέχνη El arte de • یلدمه رنه • της ενσυναίσθησης • Kunsten å empati • Die Kunst der Empathie -

Sing Me a Sad Song and Make Me Feel Better": Exploring Rewards Related to Liking Familiar Sad Music

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 10-3-2015 "Sing me a sad song and make me feel better": Exploring rewards related to liking familiar sad music John D. Hogue Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons, and the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Hogue, John D., ""Sing me a sad song and make me feel better": Exploring rewards related to liking familiar sad music" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 469. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/469 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "SING ME A SAD SONG AND MAKE ME FEEL BETTER": EXPLORING REWARDS RELATED TO LIKING FAMILIAR SAD MUSIC John D. Hogue 79 Pages Hogue (2013) tested some of Levinson's (1997) theoretical ideas about why people like listening to songs that make them sad. Particularly, Hogue tested Levinson's ideas of communion, mediation, savoring feeling, and how absorption interacted with the songs to affect communion and the emotion. Hogue, however, did not use musical stimuli that were familiar to the participants, which is a precursor to Levinson's (1997) theory. This thesis retested Levinson's theory comparing familiar songs against unfamiliar songs and songs from another participant. Data were collected from 82 participants. Each participant provided songs that induced happiness and songs that induced sadness. -

Cyclic Defrost Magazine Issue 11

SUSPEND YOUR DISBELIEF! UPDATE ##### “Guaranteed to turn heads” FLUX “Caribou’s new album is fan-fucking-tastic" RIP & BURN #### “It still sounds like nothing else on Featuring members of: the planet” MODEST MOUSE,THE BETA BAND MUSIC WEEK BLOOD BROTHERS, BUILT TO SPILL “Fresh and groundbreaking... FREE ASSOCIATION,AIRBORN AUDIO a welcome PITCHFORKMEDIA PRETTY GIRLS MAKE GRAVES return from the 8.4/10 influential artist” “A highly ANTI-POP CONSORTIUM organic blend of MURDER CITY DEVILS underground hip-hop and and indie-rock” ROOTS MANUVA STYLUS B+ FORMERLY DAN SNAITH’S “Short, blunt and skitless, AGCT seethes with everything post-aught genre-fucking needs” NEW ALBUM OUT NOW ON SELF-TITLED DEBUT OUT NOW ON ISSUE 11 CONTENTS CDITORIAL 4 COVER DESIGNER: JOE SCERRI/LAKE LUSTRE Hola! Welcome to issue eleven. This issue is our first mass assault on Europe with by Bim Ricketson two thousand copies touching down at Sonar 2005 in Barcelona along with a double CD sampler of Australian music courtesy of Austrade and the Australia Council. Perhaps 8 VELURE you are one of the lucky folk sitting back in the Catalunyan sun sipping on cava sud- We welcome your contributions and contact: by Anna Burns denly discovering that there is some great music on the other side of the world, or PO Box a2073 10 MONKFLY/FREQUENCY LAB alternately you are sitting snug and warm on a couch under a doona in share house- Sydney South by Angela Stengel hold in wintery St Kilda or Newtown wondering ‘where can I get a copy of this CD?’. -

MAINE STREAM EXPLORERS Photo: Theb’S/FLCKR Photo

MAINE STREAM EXPLORERS Photo: TheB’s/FLCKR Photo: A treasure hunt to find healthy streams in Maine Authors Tom Danielson, Ph.D. ‐ Maine Department of Environmental Protection Kaila Danielson ‐ Kents Hill High School Katie Goodwin ‐ AmeriCorps Environmental Steward serving with the Maine Department of Environmental Protection Stream Explorers Coordinators Sally Stockwell ‐ Maine Audubon Hannah Young ‐ Maine Audubon Sarah Haggerty ‐ Maine Audubon Stream Explorers Partners Alanna Doughty ‐ Lakes Environmental Association Brie Holme ‐ Portland Water District Carina Brown ‐ Portland Water District Kristin Feindel ‐ Maine Department of Environmental Protection Maggie Welch ‐ Lakes Environmental Association Tom Danielson, Ph.D. ‐ Maine Department of Environmental Protection Image Credits This guide would not have been possible with the extremely talented naturalists that made these amazing photographs. These images were either open for non‐commercial use and/or were used by permission of the photographers. Please do not use these images for other purposes without contacting the photographers. Most images were edited by Kaila Danielson. Most images of macroinvertebrates were provided by Macroinvertebrates.org, with exception of the following images: Biodiversity Institute of Ontario ‐ Amphipod Brandon Woo (bugguide.net) – adult Alderfly (Sialis), adult water penny (Psephenus herricki) and adult water snipe fly (Atherix) Don Chandler (buigguide.net) ‐ Anax junius naiad Fresh Water Gastropods of North America – Amnicola and Ferrissia rivularis -

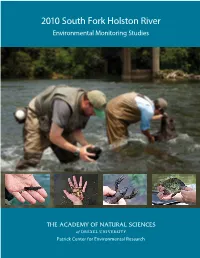

2010 South Fork Holston River Environmental Monitoring Studies

2010 South Fork Holston River Environmental Monitoring Studies Patrick Center for Environmental Research 2010 South Fork Holston River Environmental Monitoring Studies Report No. 10-04F Submitted to: Eastman Chemical Company Tennessee Operations Submitted by: Patrick Center for Environmental Research 1900 Benjamin Franklin Parkway Philadelphia, PA 19103-1195 April 20, 2012 Executive Summary he 2010 study was the seventh in a series of comprehensive studies of aquatic biota and Twater chemistry conducted by the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University in the vicinity of Kingsport, TN. Previous studies were conducted in 1965, 1967 (cursory study, primarily focusing on al- gae), 1974, 1977, 1980, 1990 and 1997. Elements of the 2010 study included analysis of land cover, basic environmental water chemistry, attached algae and aquatic macrophytes, aquatic insects, non-insect macroinvertebrates, and fish. For each study element, field samples were collected and analyzed from Scientists from the Academy's Patrick Center for Environmental Research zones located on the South Fork Holston River have conducted seven major environmental monitoring studies on the (Zones 2, 3 and 5), Big Sluice (Zone 4), mainstem South Fork Holston River since 1965. Holston River (Zone 6), and Horse Creek (Zones HC1and HC2), the approximate locations of which are shown below. The design of the 2010 study was very similar to that of previous surveys, allowing comparisons among surveys. In addition, two areas of potential local impacts were assessed for the first time: Big Tree Spring (BTS, located on the South Fork within Zone 2) and Kit Bottom (KU and KL in the Big Sluice, upstream of Zone 4). -

A List of Cuban Lepidoptera (Arthropoda: Insecta)

TERMS OF USE This pdf is provided by Magnolia Press for private/research use. Commercial sale or deposition in a public library or website is prohibited. Zootaxa 3384: 1–59 (2012) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2012 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A list of Cuban Lepidoptera (Arthropoda: Insecta) RAYNER NÚÑEZ AGUILA1,3 & ALEJANDRO BARRO CAÑAMERO2 1División de Colecciones Zoológicas y Sistemática, Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática, Carretera de Varona km 3. 5, Capdevila, Boyeros, Ciudad de La Habana, Cuba. CP 11900. Habana 19 2Facultad de Biología, Universidad de La Habana, 25 esq. J, Vedado, Plaza de La Revolución, La Habana, Cuba. 3Corresponding author. E-mail: rayner@ecologia. cu Table of contents Abstract . 1 Introduction . 1 Materials and methods. 2 Results and discussion . 2 List of the Lepidoptera of Cuba . 4 Notes . 48 Acknowledgments . 51 References . 51 Appendix . 56 Abstract A total of 1557 species belonging to 56 families of the order Lepidoptera is listed from Cuba, along with the source of each record. Additional literature references treating Cuban Lepidoptera are also provided. The list is based primarily on literature records, although some collections were examined: the Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática collection, Havana, Cuba; the Museo Felipe Poey collection, University of Havana; the Fernando de Zayas private collection, Havana; and the United States National Museum collection, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC. One family, Schreckensteinidae, and 113 species constitute new records to the Cuban fauna. The following nomenclatural changes are proposed: Paucivena hoffmanni (Koehler 1939) (Psychidae), new comb., and Gonodontodes chionosticta Hampson 1913 (Erebidae), syn. -

Molecular Systematics of Noctuoidea (Insecta, Lepidoptera)

TURUN YLIOPISTON JULKAISUJA ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS TURKUENSIS SARJA - SER. AII OSA - TOM. 268 BIOLOGICA - GEOGRAPHICA - GEOLOGICA MOLECULAR SYSTEMATICS OF NOCTUOIDEA (INSECTA, LEPIDOPTERA) REZA ZAHIRI TURUN YLIOPISTO UNIVERSITY OF TURKU Turku 2012 From the Laboratory of Genetics, Division of Genetics and Physiology, Department of Biology, University of Turku, FIN-20012, Finland Supervised by: Docent Niklas Wahlberg University of Turku Finland Co-advised by: Ph.D. J. Donald Lafontaine Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes Canada Ph.D. Ian J. Kitching Natural History Museum U.K. Ph.D. Jeremy D. Holloway Natural History Museum U.K. Reviewed by: Professor Charles Mitter University of Maryland U.S.A. Dr. Tommi Nyman University of Eastern Finland Finland Examined by: Dr. Erik J. van Nieukerken Netherlands Centre for Biodiversity Naturalis, Leiden The Netherlands Cover image: phylogenetic tree of Noctuoidea ISBN 978-951-29-5014-0 (PRINT) ISBN 978-951-29-5015-7 (PDF) ISSN 0082-6979 Painosalama Oy – Turku, Finland 2012 To Maryam, my mother and father MOLECULAR SYSTEMATICS OF NOCTUOIDEA (INSECTA, LEPIDOPTERA) Reza Zahiri This thesis is based on the following original research contributions, which are referred to in the text by their Roman numerals: I Zahiri, R, Kitching, IJ, Lafontaine, JD, Mutanen, M, Kaila, L, Holloway, JD & Wahlberg, N (2011) A new molecular phylogeny offers hope for a stable family-level classification of the Noctuoidea (Lepidoptera). Zoologica Scripta, 40, 158–173 II Zahiri, R, Holloway, JD, Kitching, IJ, Lafontaine, JD, Mutanen, M & Wahlberg, N (2012) Molecular phylogenetics of Erebidae (Lepidoptera, Noctuoidea). Systematic Entomology, 37,102–124 III Zaspel, JM, Zahiri, R, Hoy, MA, Janzen, D, Weller, SJ & Wahlberg, N (2012) A molecular phylogenetic analysis of the vampire moths and their fruit-piercing relatives (Lepidoptera: Erebidae: Calpinae). -

Opcu V30 1938 39 02.Pdf

CORNELL UNIVERSITY OFFICIAL PUBLICATION Vol. 30 July 15, 1938 No. 2 Forty-sixth Annual President's Report by Edmund Ezra Day 1937-38 With appendices containing a summary of financial operations, and reports of the Deans and other officers PUBLISHED BY CORNELL UNIVERSITY AT ITHACA, N. Y. Monthly in September, October, and November Semi-monthly, December to August inclusive [Entered as second-class matter, December 14, 1916, at the post office at Ithaca, New York, under the act of August 24, 1912] CONTENTS PAGES President's Report 5 Summary of Financial Operations ... 22 Appendices I Report of the Dean of the University Faculty i II Report of the Dean of the Graduate School iv III Report of the Dean of the College of Arts and Sci ences . xii IV Report of the Dean of the Law School xix V Report of the Dean of the Medical College xxvi VI Report of the Acting Secretary of the Ithaca Divi sion of the Medical College xxx VII Report of the Dean of the New York State Veteri nary College xxxiii VIII Report of the New York State College of Agricul ture and of the Cornell University Agricultural Experiment Station xxxvi IX Report of the New York State Agricultural Experi ment Station at Geneva xl X Report of the Dean of the New York State College of Home Economics , xlii XI Report of the Acting Dean of the College of Archi tecture xlvi XII Report of the Dean of the College of Engineering . 1 XIII Report of the Director of the Graduate School of Education Iii XIV Report of the Administrative Board of the Summer Session lvii XV Report of the Dean of Women.