A Study of Character and Fate in the Novels of Graham Greene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pax Ecclesia: Globalization and Catholic Literary Modernism

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2011 Pax Ecclesia: Globalization and Catholic Literary Modernism Christopher Wachal Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Wachal, Christopher, "Pax Ecclesia: Globalization and Catholic Literary Modernism" (2011). Dissertations. 181. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/181 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2011 Christopher Wachal LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO PAX ECCLESIA: GLOBALIZATION AND CATHOLIC LITERARY MODERNISM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN ENGLISH BY CHRISTOPHER B. WACHAL CHICAGO, IL MAY 2011 Copyright by Christopher B. Wachal, 2011 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Nothing big worth undertaking is undertaken alone. It would certainly be dishonest for me to claim that the intellectual journey of which this text is the fruition has been propelled forward solely by my own energy and momentum. There have been many who have contributed to its completion – too many, perhaps, to be done justice in so short a space as this. Nonetheless, I would like to extend my sincere thanks to some of those whose assistance I most appreciate. My dissertation director, Fr. Mark Bosco, has been both a guide and an inspiration throughout my time at Loyola University Chicago. -

Graham Greene Exhibition Catalogue

The Cherry Record Collection of Josephine Reid’s Papers and Books Relating to Our thanks to the following donors who made the acquisition possible: Paul Almond (1949) GRAHAM GREENE Professor John Stephenson (1953) Professor John-Christopher Spender (1957) Roger Jefferies (1957) Paul Lewis (1958) Peter Buckman (1959) Matthew Nimetz (1960) Doug Rosenthal (1961) Alan James (1962) Stephen Crew (1964) Jim Rogers (1964) Emeritus Professor Paul Crittenden (1965) Alan Heeks (1966) Geoff Wright (1967) Neil Record (1972) Julie Record Richard Jones (1977) Mark Storey (1981) Danny Truell (1982) Alison Roberts (1984) Claire Foster-Gilbert (1984) Virginia Preston (1985) Richard Locke (1985) Jonathan Lewin (1992) Adam Dixon (1994) Sarah Longair (1998) Jo Valentine (2001) Jeff Kulkarni (2001) Sean McDaniel (2002) Alice McDaniel (2003) Blackwell Charitable Trust Friends of the National Libraries ISBN 978-1-78280-500-7 An exhibition held at BALLIOL COLLEGE HISTORIC COLLECTIONS CENTRE 9 781782 805007 > ST CROSS CHURCH, ST CROSS ROAD, OXFORD 25 & 26 April 2015 EXHIBITION AND CATALOGUE BY Naomi Tiley Librarian, Balliol College Anna Sander Archivist, Balliol College FOREWORD BY Sir Anthony Kenny Master of Balliol College 1978–1989 Seamus Perry COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Fellow Librarian, Balliol College Studio portrait of Josephine Reid taken in the late 1940s or early Neil Record 1950s. Photographer unknown. Balliol 1972 Handwriting © Josephine Reid’s Estate Details from postcards from Graham Greene to Josephine Reid © Verdant SA. The organisers are indebted to -

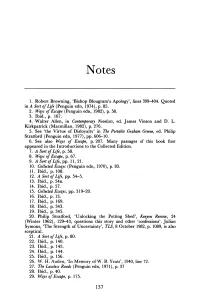

'Bishop Blougram's Apology', Lines 39~04. Quoted in a Sort of Life (Penguin Edn, 1974), P

Notes 1. Robert Browning, 'Bishop Blougram's Apology', lines 39~04. Quoted in A Sort of Life (Penguin edn, 1974), p. 85. 2. Wqys of Escape (Penguin edn, 1982), p. 58. 3. Ibid., p. 167. 4. Walter Allen, in Contemporary Novelists, ed. James Vinson and D. L. Kirkpatrick (Macmillan, 1982), p. 276. 5. See 'the Virtue of Disloyalty' in The Portable Graham Greene, ed. Philip Stratford (Penguin edn, 1977), pp. 606-10. 6. See also Ways of Escape, p. 207. Many passages of this book first appeared in the Introductions to the Collected Edition. 7. A Sort of Life, p. 58. 8. Ways of Escape, p. 67. 9. A Sort of Life, pp. 11, 21. 10. Collected Essays (Penguin edn, 1970), p. 83. 11. Ibid., p. 108. 12. A Sort of Life, pp. 54-5. 13. Ibid., p. 54n. 14. Ibid., p. 57. 15. Collected Essays, pp. 319-20. 16. Ibid., p. 13. 17. Ibid., p. 169. 18. Ibid., p. 343. 19. Ibid., p. 345. 20. Philip Stratford, 'Unlocking the Potting Shed', KeT!Jon Review, 24 (Winter 1962), 129-43, questions this story and other 'confessions'. Julian Symons, 'The Strength of Uncertainty', TLS, 8 October 1982, p. 1089, is also sceptical. 21. A Sort of Life, p. 80. 22. Ibid., p. 140. 23. Ibid., p. 145. 24. Ibid., p. 144. 25. Ibid., p. 156. 26. W. H. Auden, 'In Memory ofW. B. Yeats', 1940, line 72. 27. The Lawless Roads (Penguin edn, 1971), p. 37 28. Ibid., p. 40. 29. Ways of Escape, p. 175. 137 138 Notes 30. Ibid., p. -

Andrew Martin Is an Author, Journalist and Broadcaster. His Previous Books with Profile Are Underground, Overground and Belles and Whistles

ANDREW MARTIN is an author, journalist and broadcaster. His previous books with Profile are Underground, Overground and Belles and Whistles. He has written for the Guardian, Evening Standard, Independent on Sunday, Daily Telegraph and New Statesman, amongst many others. His ‘Jim Stringer’ series of novels based around railways is published by Faber. His latest novel, Soot, is set in late eighteenth-century York. Praise for Night Trains ‘You do not have to be a trainspotter to enjoy this book. It is social history, a kind of epitaph to a way of travel that seems to be lost, at least in Europe.’ Spectator ‘A delightful book … charmingly combines Martin’s own travels, as he recreates journeys on famous trains such as the Orient Express, with a serious, occasionally geeky, history of those elegant wagons lits of the past … Even if you’re not into the detail of rail gauges, this book is the perfect companion as you wait for the 8.10 from Hove.’ Observer ‘Excellent … Mr Martin paints a vivid picture of this world on rails … he proves a witty companion who wears his knowledge lightly’ Country Life ‘Andrew Martin has cornered the train market. He is the Bard of the Buffer, the Balladeer of the Blue Train, the Laureate of Lost Property … I picked up Night Trains knowing that I would be entertained, but also in the hope that his many years of experience would teach me how to sleep on a sleeper … Andrew Martin is the best sort of travel writer: inquisitive, knowledgeable, lively, congenial. He is also very funny, while never letting the humour drive reality, rather than vice versa. -

Nesetrilovai Reflection1930s O

University of Pardubice Faculty of Arts and Philosophy Reflection of the 1930´s British Society in Graham Greene´s Brighton Rock Iva Nešetřilová Bachelor thesis 2017 Prohlašuji: Tuto práci jsem vypracovala samostatně. Veškeré literární prameny a informace, které jsem v práci využila, jsou uvedeny v seznamu použité literatury. Byla jsem seznámena s tím, že se na moji práci vztahují práva a povinnosti vyplývající ze zákona č. 121/2000 Sb., autorský zákon, zejména se skutečností, že Univerzita Pardubice má právo na uzavření licenční smlouvy o užití této práce jako školního díla podle § 60 odst. 1 autorského zákona, a s tím, že pokud dojde k užití této práce mnou nebo bude poskytnuta licence o užití jinému subjektu, je Univerzita Pardubice oprávněna ode mne požadovat přiměřený příspěvek na úhradu nákladů, které na vytvoření díla vynaložila, a to podle okolností až do jejich skutečné výše. Souhlasím s prezenčním zpřístupněním své práce v Univerzitní knihovně. V Pardubicích dne 17.3.2017 Iva Nešetřilová Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Mgr. Olga Roebuck, M.Litt. Ph.D. for giving me the opportunity to choose this topic, for her professional help, advice, and, especially, for the time she had spent when consulting my work. Annotation This paper examines and analyses the reflection of British Society in the novel Brighton Rock by Graham Green. The first part explores the situation in Britain around the 1930s, the period when the book was written and published, and briefly focuses on the changing landscape brought about by the Depression and aftermath of the First World War. The emphasis is confined mostly to how these changes affected the lower classes, and a brief description of what constitutes working class is provided. -

Cervantes and the Spanish Baroque Aesthetics in the Novels of Graham Greene

TESIS DOCTORAL Título Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene Autor/es Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Director/es Carlos Villar Flor Facultad Facultad de Letras y de la Educación Titulación Departamento Filologías Modernas Curso Académico Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene, tesis doctoral de Ismael Ibáñez Rosales, dirigida por Carlos Villar Flor (publicada por la Universidad de La Rioja), se difunde bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Unported. Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden solicitarse a los titulares del copyright. © El autor © Universidad de La Rioja, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2016 publicaciones.unirioja.es E-mail: [email protected] CERVANTES AND THE SPANISH BAROQUE AESTHETICS IN THE NOVELS OF GRAHAM GREENE By Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Supervised by Carlos Villar Flor Ph.D A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At University of La Rioja, Spain. 2015 Ibáñez-Rosales 2 Ibáñez-Rosales CONTENTS Abbreviations ………………………………………………………………………….......5 INTRODUCTION ...…………………………………………………………...….7 METHODOLOGY AND STRUCTURE………………………………….……..12 STATE OF THE ART ..……….………………………………………………...31 PART I: SPAIN, CATHOLICISM AND THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN (CATHOLIC) NOVEL………………………………………38 I.1 A CATHOLIC NOVEL?......................................................................39 I.2 ENGLISH CATHOLICISM………………………………………….58 I.3 THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN -

Introduction

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. Graham Greene (ed.), The Old School (London: Jonathan Cape, 1934) 7-8. (Hereafter OS.) 2. Ibid., 105, 17. 3. Graham Greene, A Sort of Life (London: Bodley Head, 1971) 72. (Hereafter SL.) 4. OS, 256. 5. George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier (London: Gollancz, 1937) 171. 6. OS, 8. 7. Barbara Greene, Too Late to Turn Back (London: Settle and Bendall, 1981) ix. 8. Graham Greene, Collected Essays (London: Bodley Head, 1969) 14. (Hereafter CE.) 9. Graham Greene, The Lawless Roads (London: Longmans, Green, 1939) 10. (Hereafter LR.) 10. Marie-Franc;oise Allain, The Other Man (London: Bodley Head, 1983) 25. (Hereafter OM). 11. SL, 46. 12. Ibid., 19, 18. 13. Michael Tracey, A Variety of Lives (London: Bodley Head, 1983) 4-7. 14. Peter Quennell, The Marble Foot (London: Collins, 1976) 15. 15. Claud Cockburn, Claud Cockburn Sums Up (London: Quartet, 1981) 19-21. 16. Ibid. 17. LR, 12. 18. Graham Greene, Ways of Escape (Toronto: Lester and Orpen Dennys, 1980) 62. (Hereafter WE.) 19. Graham Greene, Journey Without Maps (London: Heinemann, 1962) 11. (Hereafter JWM). 20. Christopher Isherwood, Foreword, in Edward Upward, The Railway Accident and Other Stories (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972) 34. 21. Virginia Woolf, 'The Leaning Tower', in The Moment and Other Essays (NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1974) 128-54. 22. JWM, 4-10. 23. Cockburn, 21. 24. Ibid. 25. WE, 32. 26. Graham Greene, 'Analysis of a Journey', Spectator (September 27, 1935) 460. 27. Samuel Hynes, The Auden Generation (New York: Viking, 1977) 228. 28. ]WM, 87, 92. 29. Ibid., 272, 288, 278. -

Graham Greene and the Idea of Childhood

GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD APPROVED: Major Professor /?. /V?. Minor Professor g.>. Director of the Department of English D ean of the Graduate School GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD THESIS Presented, to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Martha Frances Bell, B. A. Denton, Texas June, 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. FROM ROMANCE TO REALISM 12 III. FROM INNOCENCE TO EXPERIENCE 32 IV. FROM BOREDOM TO TERROR 47 V, FROM MELODRAMA TO TRAGEDY 54 VI. FROM SENTIMENT TO SUICIDE 73 VII. FROM SYMPATHY TO SAINTHOOD 97 VIII. CONCLUSION: FROM ORIGINAL SIN TO SALVATION 115 BIBLIOGRAPHY 121 ill CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A .narked preoccupation with childhood is evident throughout the works of Graham Greene; it receives most obvious expression its his con- cern with the idea that the course of a man's life is determined during his early years, but many of his other obsessive themes, such as betray- al, pursuit, and failure, may be seen to have their roots in general types of experience 'which Green® evidently believes to be common to all children, Disappointments, in the form of "something hoped for not happening, something promised not fulfilled, something exciting turning • dull," * ar>d the forced recognition of the enormous gap between the ideal and the actual mark the transition from childhood to maturity for Greene, who has attempted to indicate in his fiction that great harm may be done by aclults who refuse to acknowledge that gap. -

Wireless Women: the “Mass” Retreat of Brighton Rock Jeffrey Sconce Northwestern University

47 Wireless Women: The “Mass” Retreat of Brighton Rock Jeffrey Sconce Northwestern University All popular fi ction must feature a romantic couple, and so it is in the open- ing pages of Brighton Rock (1938) that Graham Greene introduces Pinkie and Rose, the teenagers whose abrasive courtship and perverse marriage will both enact and travesty this convention as the novel unfolds. When Pinkie fi rst meets Rose, she is working at Snow’s as a waitress. Entering the establishment, Pinkie encounters a wireless set “droning a programme of weary music broadcast by a cinema organist—a great vox humana trembl[ing] across the crumby stained desert of used cloths: the world’s wet mouth lamenting over life” (24). This reference to the weary lamentations of wireless remains an isolated detail until moments before Pinkie takes his fatal plunge over the cliff in the novel’s closing pages. Having taken Rose up the coast from Brighton with plans to facilitate her suicide, the couple sits for a few awkward moments in an empty hotel lounge. As Rose works on her half of the couple’s double-suicide note, to be left behind for the benefi t of “Daily Express readers, to what one called the world” (260), wireless makes a brief but meaningful re-appearance as that world speaks back. “The wireless was hidden behind a potted plant; a violin came wailing out, the notes shaken by atmospherics,” writes Greene (250). Later, the violin fades away and “a time signal pinged through the rain. A voice behind the plant gave them the weather report—storms coming up from the Continent, a depression in the Atlantic, tomorrow’s forecast” (251). -

"Freedom and Alienation in Graham Greene's "Brighton Rock," Albert Camus' "The Plague," and Other Related Texts."

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses "Freedom and alienation in Graham Greene's "Brighton Rock," Albert Camus' "The Plague," and other related texts." Breeze, Brian How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Breeze, Brian (2005) "Freedom and alienation in Graham Greene's "Brighton Rock," Albert Camus' "The Plague," and other related texts.". thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa42557 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ FREEDOM AND ALIENATION in Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock, Albert Camus’ The Plague, and other related texts. BRIAN BREEZE M.Phil. 2005 UNIVERSITY OF WALES SWANSEA PRIFYSGOL CYMRU ABERTAWE ProQuest N um ber: 10805306 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

The Ambivalent Catholic Modernity of Graham Greene’S

THE AMBIVALENT CATHOLIC MODERNITY OF GRAHAM GREENE’S BRIGHTON ROCK AND THE POWER AND THE GLORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In English By Karl O’Hanlon, B.A. Washington D.C. 28 th April, 2010 THE AMBIVALENT CATHOLIC MODERNITY OF GRAHAM GREENE’S BRIGHTON ROCK AND THE POWER AND THE GLORY Karl O’Hanlon, B.A. Thesis Advisor: John Pfordresher, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This thesis argues that the “religious sense” which emerged from Graham Greene’s Catholicism provides the basis for the critique of the ethics of modernity in his novels Brighton Rock (1938) and The Power and the Glory (1940). In his depiction of the self-righteous Ida Arnold in Brighton Rock , Greene elicits some problems inherent in modern ethical theory, comparing secular “right and wrong” unfavourably with a religious sense of “good and evil.” I suggest that the antimodern aspects of Pinkie in Brighton Rock are ultimately renounced by Greene as potentially dangerous, and in The Power and the Glory his critique of modernity evolves to a more ambivalent dialectic, in which facets of modernity are affirmed as well as rejected. I argue that this evolution in stance constitutes Greene’s search for a new philosophical and literary idiom – a “Catholic modernity.” ii With sincere thanks to John Pfordresher, for the great conversations about Greene, encouragement, careful reading, and patience in waiting for new chapter drafts, without which this thesis would have been much the poorer. -

The Mystery of Evil in Five Works by Graham Greene

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1984 The Mystery of Evil in Five Works by Graham Greene Stephen D. Arata College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Arata, Stephen D., "The Mystery of Evil in Five Works by Graham Greene" (1984). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625259. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-6j1s-0j28 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Mystery of Evil // in Five Works by Graham Greene A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Stephen D. Arata 1984 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts /;. WiaCe- Author Approved, September 1984 ABSTRACT Graham Greene's works in the 1930s reveal his obsession with the nature and source of evil in the world. The world for Greene is a sad and frightening place, where betrayal, injustice, and cruelty are the norm. His books of the 1930s, culminating in Brighton Rock (1938), are all, on some level, attempts to explain why this is so.