Pax Ecclesia: Globalization and Catholic Literary Modernism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Bishop Blougram's Apology', Lines 39~04. Quoted in a Sort of Life (Penguin Edn, 1974), P

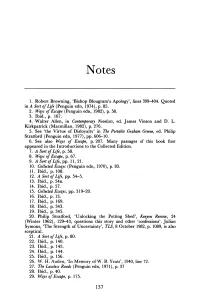

Notes 1. Robert Browning, 'Bishop Blougram's Apology', lines 39~04. Quoted in A Sort of Life (Penguin edn, 1974), p. 85. 2. Wqys of Escape (Penguin edn, 1982), p. 58. 3. Ibid., p. 167. 4. Walter Allen, in Contemporary Novelists, ed. James Vinson and D. L. Kirkpatrick (Macmillan, 1982), p. 276. 5. See 'the Virtue of Disloyalty' in The Portable Graham Greene, ed. Philip Stratford (Penguin edn, 1977), pp. 606-10. 6. See also Ways of Escape, p. 207. Many passages of this book first appeared in the Introductions to the Collected Edition. 7. A Sort of Life, p. 58. 8. Ways of Escape, p. 67. 9. A Sort of Life, pp. 11, 21. 10. Collected Essays (Penguin edn, 1970), p. 83. 11. Ibid., p. 108. 12. A Sort of Life, pp. 54-5. 13. Ibid., p. 54n. 14. Ibid., p. 57. 15. Collected Essays, pp. 319-20. 16. Ibid., p. 13. 17. Ibid., p. 169. 18. Ibid., p. 343. 19. Ibid., p. 345. 20. Philip Stratford, 'Unlocking the Potting Shed', KeT!Jon Review, 24 (Winter 1962), 129-43, questions this story and other 'confessions'. Julian Symons, 'The Strength of Uncertainty', TLS, 8 October 1982, p. 1089, is also sceptical. 21. A Sort of Life, p. 80. 22. Ibid., p. 140. 23. Ibid., p. 145. 24. Ibid., p. 144. 25. Ibid., p. 156. 26. W. H. Auden, 'In Memory ofW. B. Yeats', 1940, line 72. 27. The Lawless Roads (Penguin edn, 1971), p. 37 28. Ibid., p. 40. 29. Ways of Escape, p. 175. 137 138 Notes 30. Ibid., p. -

The Importance of the Catholic School Ethos Or Four Men in a Bateau

THE AMERICAN COVENANT, CATHOLIC ANTHROPOLOGY AND EDUCATING FOR AMERICAN CITIZENSHIP: THE IMPORTANCE OF THE CATHOLIC SCHOOL ETHOS OR FOUR MEN IN A BATEAU A dissertation submitted to the Kent State University College of Education, Health, and Human Services in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Ruth Joy August 2018 A dissertation written by Ruth Joy B.S., Kent State University, 1969 M.S., Kent State University, 2001 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2018 Approved by _________________________, Director, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Natasha Levinson _________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Averil McClelland _________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Catherine E. Hackney Accepted by _________________________, Director, School of Foundations, Leadership and Kimberly S. Schimmel Administration ........................ _________________________, Dean, College of Education, Health and Human Services James C. Hannon ii JOY, RUTH, Ph.D., August 2018 Cultural Foundations ........................ of Education THE AMERICAN COVENANT, CATHOLIC ANTHROPOLOGY AND EDUCATING FOR AMERICAN CITIZENSHIP: THE IMPORTANCE OF THE CATHOLIC SCHOOL ETHOS. OR, FOUR MEN IN A BATEAU (213 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Natasha Levinson, Ph. D. Dozens of academic studies over the course of the past four or five decades have shown empirically that Catholic schools, according to a wide array of standards and measures, are the best schools at producing good American citizens. This dissertation proposes that this is so is partly because the schools are infused with the Catholic ethos (also called the Catholic Imagination or the Analogical Imagination) and its approach to the world in general. A large part of this ethos is based upon Catholic Anthropology, the Church’s teaching about the nature of the human person and his or her relationship to other people, to Society, to the State, and to God. -

Copyright by Maeri Megumi 2014

Copyright by Maeri Megumi 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Maeri Megumi Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Religion, Nation, Art: Christianity and Modern Japanese Literature Committee: Kirsten C. Fischer, Supervisor Sung-Sheng Yvonne Chang Anne M. Martinez Nancy K. Stalker John W. Traphagan Susan J. Napier Religion, Nation, Art: Christianity and Modern Japanese Literature by Maeri Megumi, B.HOME ECONOMICS; M.A.; M.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2014 Acknowledgements I would like to express the deepest gratitude to my advisor and mentor, Dr. Kirsten Cather (Fischer). Without her guidance and encouragement throughout the long graduate student life in Austin, Texas, this dissertation would not have been possible. Her insight and timely advice have always been the source of my inspiration, and her positive energy and patience helped me tremendously in many ways. I am also indebted to my other committee members: Dr. Nancy Stalker, Dr. John Traphagan, Dr. Yvonne Chang, Dr. Anne Martinez, and Dr. Susan Napier. They nourished my academic development throughout the course of my graduate career both directly and indirectly, and I am particularly thankful for their invaluable input and advice in shaping this dissertation. I would like to thank the Department of Asian Studies for providing a friendly environment, and to the University of Texas for offering me generous fellowships to make my graduate study, and this dissertation, possible. -

Notes on Contributors 7 6 7

NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS 7 6 7 NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS ALLEN, Walter. Novelist and Literary Critic. Author of six novels (the most recent being All in a Lifetime, 1959); several critical works, including Arnold Bennett, 1948; Reading a Novel, 1949 (revised, 1956); Joyce Cary, 1953 (revised, 1971); The English Novel, 1954; Six Great Novelists, 1955; The Novel Today, 1955 (revised, 1966); George Eliot, 1964; and The Modern Novel in Britain and the United States, 1964; and of travel books, social history, and books for children. Editor of Writers on Writing, 1948, and of The Roaring Queen by Wyndham Lewis, 1973. Has taught at several universities in Britain, the United States, and Canada, and been an editor of the New Statesman. Essays: Richard Hughes; Ring Lardner; Dorothy Richardson; H. G. Wells. ANDERSON, David D. Professor of American Thought and Language, Michigan State University, East Lansing; Editor of University College Quarterly and Midamerica. Author of Louis Bromfield, 1964; Critical Studies in American Literature, 1964; Sherwood Anderson, 1967; Anderson's "Winesburg, Ohio," 1967; Brand Whitlock, 1968; Abraham Lincoln, 1970; Robert Ingersoll, 1972; Woodrow Wilson, 1975. Editor or Co-Editor of The Black Experience, 1969; The Literary Works of Lincoln, 1970; The Dark and Tangled Path, 1971 ; Sunshine and Smoke, 1971. Essay: Louis Bromfield. ANGLE, James. Assistant Professor of English, Eastern Michigan University, Ypsilanti. Author of verse and fiction in periodicals, and of an article on Edward Lewis Wallant in Kansas Quarterly, Fall 1975. Essay: Edward Lewis Wallant. ASHLEY, Leonard R.N. Professor of English, Brooklyn College, City University of New York. Author of Colley Cibber, 1965; 19th-Century British Drama, 1967; Authorship and Evidence: A Study of Attribution and the Renaissance Drama, 1968; History of the Short Story, 1968; George Peele: The Man and His Work, 1970. -

Hunger on the Rise in Corporate America Try Where Five Years of a Bloody Campaign Led by the Regime in Riyadh Have Shattered the Health System

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 12 Pages Price 40,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 39th year No.13638 Monday APRIL 13, 2020 Farvardin 25, 1399 Sha’aban 19, 1441 Iran says investigating Afghanistan thanks Iran Can the Iranian Top Iranian scholar possibility of coronavirus for free services to refugees clubs ask players to Hassan Anusheh as biological warfare 3 during COVID-19 10 take pay cut? 11 passes away at 75 12 Tax income up 31% in a year TEHRAN — Iran’s tax revenue has as value added tax (VAT)”, IRIB reported. increased 31 percent in the past Ira- Parsa also said that the country has nian calendar year (ended on March gained projected tax income by 102 percent Hunger on the rise 19), Omid- Ali Parsa, the head of Iran’s in the past year, and put the average tax National Tax Administration (INTA), income growth at 21 percent during the announced. previous five years. Putting the country’s tax income at 1.43 The head of National Tax Administra- quadrillion rials (about $34.04 billion) in tion further mentioned preventing from tax the previous year, the official said, “We could evasion as one of the prioritized programs collect 250 trillion rials (about $5.9 billion) of INTA. 4 in corporate See page 3 Discover Ozbaki hill that goes down 9,000 years in history America TEHRAN — “Nine thousand years of his- Ozbaki hill indicate some kind of com- tory.” It’s a phrase that may seem enough mercial link between Susa in Khuzestan to draw the attention of every history buff and this in Tehran province,” according across the globe. -

© Copyrighted by Charles Ernest Davis

SELECTED WORKS OF LITERATURE AND READABILITY Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Davis, Charles Ernest, 1933- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 00:54:12 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/288393 This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 70-5237 DAVIS, Charles Ernest, 1933- SELECTED WORKS OF LITERATURE AND READABILITY. University of Arizona, Ph.D., 1969 Education, theory and practice University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan © COPYRIGHTED BY CHARLES ERNEST DAVIS 1970 iii SELECTED WORKS OF LITERATURE AND READABILITY by Charles Ernest Davis A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF SECONDARY EDUCATION In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY .In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 9 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by Charles Ernest Davis entitled Selected Works of Literature and Readability be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy PqulA 1- So- 6G Dissertation Director Date After inspection of the final copy of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Committee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:" *7-Mtf - 6 7-So IdL 7/3a This approval and acceptance is contingent on the candidate's adequate performance and defense of this dissertation at the final oral examination; The inclusion of this sheet bound into the library copy of the dissertation is evidence of satisfactory performance at the final examination. -

Poetry at Catholic Imagination Conference at the Catholic

Poetry at Catholic Imagination Conference At the Catholic Imagination Conference, I saw the poets Lawrence Joseph and Fanny Howe read some of their poems and talk about their lives in relation to their poetry. First, Fanny Howe read some of her work and talked a little bit about when she had written them. Then, Lawrence Joseph followedby doing the sarrie thing. After they had finished there was a guy who sat up there with them and asked them questions to go a little deeper into their thoughts about their poetry and relating it to God and the Catholic religion. I have never been fl-big poetry reader� but I do enjoy it when I read it. I think that poets are very interesting people with a special way of thinking that they can organize all their thoughts into a specific set of words that without being large in length can have the strongest messages. I was able to take some notes during the conference and write some of the things that both Lawrence Joseph and Fanny Howe said in general and specific to religion that were interesting to me. "I believe that God doesn't love me" This was what Fanny said in the beginning of her discussion. I was really surprised when I heard this, and I felt like many other people in the room were too. Some of the things she said were a very interesting way of approaching religion and I thought that was mind opening to hear her talk about. She went on to discuss prayer and poetry and said, "Poetry is the ultimate act of attention nothing courageous about it, attention is prayer, attention to what God isn't paying attention to". -

American Catholics in the Protestant Imagination Carroll, Michael P

American Catholics in the Protestant Imagination Carroll, Michael P. Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Carroll, Michael P. American Catholics in the Protestant Imagination: Rethinking the Academic Study of Religion. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.3479. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/3479 [ Access provided at 23 Sep 2021 22:11 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. American Catholics in the Protestant Imagination This page intentionally left blank American Catholics in the Protestant Imagination Rethinking the Academic Study of Religion michael p. carroll The Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore This book has been brought to publication with the generous assistance of the J. B. Smallman Publication Fund and the Faculty of Social Science of The University of Western Ontario. © 2007 The Johns Hopkins University Press All rights reserved. Published 2007 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 246897531 The Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Carroll, Michael P., 1944– American Catholics in the Protestant imagination : rethinking the academic study of religion / Michael P. Carroll. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8018-8683-6 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8018-8683-X (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Catholics—United States—History. 2. Catholics—United States— Historiography. I. Title. BX1406.3.C375 2007 282Ј.73—dc22 2007006282 A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Through a Glass Darkly-Healing and the Religious Imagination

HEALING SPACES Through a Glass Darkly Healing and the Religious Imagination ZENI FOX, PhD he use of design to create healing environments draws upon many aspects of human creativity. One source is religious imagination, which is the capacity to envision the T transcendent when perceiving a specific, concrete and earthly reality. Two examples — one from the Middle Ages that reflects traditional themes and one recent example focused on the contemporary world — allow for an entry point for the exploration of the relationship between healing and the religious imagination. Years ago, the BBC created a video, “The Many of Art in New York City mounted the exhibition, Images of Christ.” It included one image of the “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagi- crucifixion that depicted Jesus covered with nation.” It drew the largest attendance of any exhi- sores from St. Anthony’s Fire, a disease that was bition there, ever.1 The exhibit opened with a quo- a great scourge in medieval times. Known as the tation from the late Fr. Andrew Greeley, a noted “Isenheim Altarpiece,” it is a triptych considered sociologist and author, about the religious imagi- to be the German 16th-century painter Matthias nation: “Catholics live in an enchanted world: a Grünewald’s greatest work. It was commissioned world of statues and holy water, stained glass and by the Hospital Brothers of St. Anthony, an order votive candles, saints and religious medals, rosary founded for the purpose of caring for those suf- beads and holy pictures. But these Catholic para- fering from St. Anthony’s Fire and the plague. -

Allen Tate Papers Correspondence and Manuscripts 1923-1974

ALLEN TATE PAPERS CORRESPONDENCE AND MANUSCRIPTS 1923-1974 MSS # 431 Arranged and described by Molly Dohrmann July 2006 SPECIAL COLLECTIONS Jean and Alexander Heard Library Vanderbilt University 419 21st. Avenue South Nashville, Tennessee 37240 Telephone: (615) 322-2807 ALLEN TATE PAPERS Biographical Note John Orley Allen Tate was born near Winchester, Kentucky November 19, 1899. He graduated from Vanderbilt University Magna Cum Laude, Phi Beta Kappa in 1922. During this time at Vanderbilt he became one of the Fugitive poets who published their magazine The Fugitive during the years 1922-1925. Later he contributed an essay to the Agrarian manifesto I’ll Take My Stand (1930) and in 1936 he was co-editor with Herbert Agar of Who Owns America? He published poetry throughout his long career and was an accomplished man of letters writing one novel The Fathers (1938), criticism, and biographies.Tate was also the editor at The Sewanee Review from 1944-46. He received many awards for his poetry including the Bollingen Prize in 1956 and held the Chair of Poetry at the Library of Congress in 1943-44. Allen Tate was also a teacher with appointments at among others the Women’s College of the University of North Carolina, Princeton, New York University, and the University of Minnesota where he taught from 1951 until his retirement in 1968. He was married twice to the writer Caroline Gordon from 1924 to 1959. They had a daughter Nancy born in 1924. After his divorce from Caroline Gordon in 1959 he married poet Isabella Gardner. And after his divorce from Gardner in 1966 he married his former student at Minnesota Helen Heinz. -

Journal of the Short Story in English, 67

Journal of the Short Story in English Les Cahiers de la nouvelle 67 | Autumn 2016 Special Issue: Representation and Rewriting of Myths in Southern Short Fiction Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/jsse/1745 ISSN: 1969-6108 Publisher Presses universitaires de Rennes Printed version Date of publication: 1 December 2016 ISBN: 0294-0442 ISSN: 0294-04442 Electronic reference Journal of the Short Story in English, 67 | Autumn 2016, « Special Issue: Representation and Rewriting of Myths in Southern Short Fiction » [Online], Online since 01 December 2018, connection on 03 December 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/jsse/1745 This text was automatically generated on 3 December 2020. © All rights reserved 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword Michelle Ryan-Sautour and Linda Collinge-Germain Introduction Gérald Préher and Emmanuel Vernadakis Articles The "Rape Complex" in Short Fiction from the American South Ineke Bockting Ellen Glasgow's "Jordan's End": Antigone in the South Inès Casas From "Faithful Old Servant" to "Bantu Woman": Katherine Anne Porter's Approach to the Mammy Myth in "The Old Order" Susana Maria Jiménez-Placer Myth and Metaphor in James Agee's "1928 Story" Rémi Digonnet Myth for the Masses: Erskine Caldwell's "Daughter" Amélie Moisy Frontiers of Myth and Myths of the Frontier in Caroline Gordon's "Tom Rivers" and "The Captive" Elisabeth Lamothe William Faulkner's "My Grandmother Millard" (1943) and Caroline Gordon's "The Forest of the South" (1944): Comic and Tragic Versions of the Southern Belle Myth Françoise -

A Study of Character and Fate in the Novels of Graham Greene

THE DESPERATE HERO: A STUDY OF CHARACTER AND FATE IN THE NOVELS OF GRAHAM GREENE by TRISTAN R. EASTON B.A., University of British Columbia, 1969 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of English We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, 1973 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of English The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date September 23, 1973 ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis will be to show how Graham Greene's vision of man's position in the modern world changes and deepens as the author matures as a man and a novelist. The thesis will be primarily concerned with the relationship of the central characters of Greene's novels to their environment. I will try to show how this relationship, which in Greene's early novels is often fatalistic and deterministic, changes as Greene becomes more concerned with the possibilities of a spiritual and moral 'awakening' within his heroes which can perhaps counter• balance the forces of determinism.