Sharon Knolle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“White Christmas”—Bing Crosby (1942) Added to the National Registry: 2002 Essay by Cary O’Dell

“White Christmas”—Bing Crosby (1942) Added to the National Registry: 2002 Essay by Cary O’Dell Crosby’s 1945 holiday album Original release label “Holiday Inn” movie poster With the possible exception of “Silent Night,” no other song is more identified with the holiday season than “White Christmas.” And no singer is more identified with it than its originator, Bing Crosby. And, perhaps, rightfully so. Surely no other Christmas tune has ever had the commercial or cultural impact as this song or sold as many copies--50 million by most estimates, making it the best-selling record in history. Irving Berlin wrote “White Christmas” in 1940. Legends differ as to where and how though. Some say he wrote it poolside at the Biltmore Hotel in Phoenix, Arizona, a reasonable theory considering the song’s wishing for wintery weather. Some though say that’s just a good story. Furthermore, some histories say Berlin knew from the beginning that the song was going to be a massive hit but another account says when he brought it to producer-director Mark Sandrich, Berlin unassumingly described it as only “an amusing little number.” Likewise, Bing Crosby himself is said to have found the song only merely adequate at first. Regardless, everyone agrees that it was in 1942, when Sandrich was readying a Christmas- themed motion picture “Holiday Inn,” that the song made its debut. The film starred Fred Astaire and Bing Crosby and it needed a holiday song to be sung by Crosby and his leading lady, Marjorie Reynolds (whose vocals were dubbed). Enter “White Christmas.” Though the film would not be seen for many months, millions of Americans got to hear it on Christmas night, 1941, when Crosby sang it alone on his top-rated radio show “The Kraft Music Hall.” On May 29, 1942, he recorded it during the sessions for the “Holiday Inn” album issued that year. -

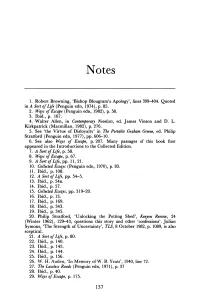

'Bishop Blougram's Apology', Lines 39~04. Quoted in a Sort of Life (Penguin Edn, 1974), P

Notes 1. Robert Browning, 'Bishop Blougram's Apology', lines 39~04. Quoted in A Sort of Life (Penguin edn, 1974), p. 85. 2. Wqys of Escape (Penguin edn, 1982), p. 58. 3. Ibid., p. 167. 4. Walter Allen, in Contemporary Novelists, ed. James Vinson and D. L. Kirkpatrick (Macmillan, 1982), p. 276. 5. See 'the Virtue of Disloyalty' in The Portable Graham Greene, ed. Philip Stratford (Penguin edn, 1977), pp. 606-10. 6. See also Ways of Escape, p. 207. Many passages of this book first appeared in the Introductions to the Collected Edition. 7. A Sort of Life, p. 58. 8. Ways of Escape, p. 67. 9. A Sort of Life, pp. 11, 21. 10. Collected Essays (Penguin edn, 1970), p. 83. 11. Ibid., p. 108. 12. A Sort of Life, pp. 54-5. 13. Ibid., p. 54n. 14. Ibid., p. 57. 15. Collected Essays, pp. 319-20. 16. Ibid., p. 13. 17. Ibid., p. 169. 18. Ibid., p. 343. 19. Ibid., p. 345. 20. Philip Stratford, 'Unlocking the Potting Shed', KeT!Jon Review, 24 (Winter 1962), 129-43, questions this story and other 'confessions'. Julian Symons, 'The Strength of Uncertainty', TLS, 8 October 1982, p. 1089, is also sceptical. 21. A Sort of Life, p. 80. 22. Ibid., p. 140. 23. Ibid., p. 145. 24. Ibid., p. 144. 25. Ibid., p. 156. 26. W. H. Auden, 'In Memory ofW. B. Yeats', 1940, line 72. 27. The Lawless Roads (Penguin edn, 1971), p. 37 28. Ibid., p. 40. 29. Ways of Escape, p. 175. 137 138 Notes 30. Ibid., p. -

HOLLYWOOD – the Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition

HOLLYWOOD – The Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition Paramount MGM 20th Century – Fox Warner Bros RKO Hollywood Oligopoly • Big 5 control first run theaters • Theater chains regional • Theaters required 100+ films/year • Big 5 share films to fill screens • Little 3 supply “B” films Hollywood Major • Producer Distributor Exhibitor • Distribution & Exhibition New York based • New York HQ determines budget, type & quantity of films Hollywood Studio • Hollywood production lots, backlots & ranches • Studio Boss • Head of Production • Story Dept Hollywood Star • Star System • Long Term Option Contract • Publicity Dept Paramount • Adolph Zukor • 1912- Famous Players • 1914- Hodkinson & Paramount • 1916– FP & Paramount merge • Producer Jesse Lasky • Director Cecil B. DeMille • Pickford, Fairbanks, Valentino • 1933- Receivership • 1936-1964 Pres.Barney Balaban • Studio Boss Y. Frank Freeman • 1966- Gulf & Western Paramount Theaters • Chicago, mid West • South • New England • Canada • Paramount Studios: Hollywood Paramount Directors Ernst Lubitsch 1892-1947 • 1926 So This Is Paris (WB) • 1929 The Love Parade • 1932 One Hour With You • 1932 Trouble in Paradise • 1933 Design for Living • 1939 Ninotchka (MGM) • 1940 The Shop Around the Corner (MGM Cecil B. DeMille 1881-1959 • 1914 THE SQUAW MAN • 1915 THE CHEAT • 1920 WHY CHANGE YOUR WIFE • 1923 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS • 1927 KING OF KINGS • 1934 CLEOPATRA • 1949 SAMSON & DELILAH • 1952 THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH • 1955 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS Paramount Directors Josef von Sternberg 1894-1969 • 1927 -

The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and Its American Legacy

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 3 (2010) 109–120 The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and its American legacy Jacqui Miller Liverpool Hope University (United Kingdom) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The French New Wave was an essentially pan-continental cinema. It was influenced both by American gangster films and French noirs, and in turn was one of the principal influences on the New Hollywood, or Hollywood renaissance, the uniquely creative period of American filmmaking running approximately from 1967–1980. This article will examine this cultural exchange and enduring cinematic legacy taking as its central intertext Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samourai (1967). Some consideration will be made of its precursors such as This Gun for Hire (Frank Tuttle, 1942) and Pickpocket (Robert Bresson, 1959) but the main emphasis will be the references made to Le Samourai throughout the New Hollywood in films such as The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971), The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974) and American Gigolo (Paul Schrader, 1980). The article will suggest that these films should not be analyzed as isolated texts but rather as composite elements within a super-text and that cross-referential study reveals the incremental layers of resonance each film’s reciprocity brings. This thesis will be explored through recurring themes such as surveillance and alienation expressed in parallel scenes, for example the subway chases in Le Samourai and The French Connection, and the protagonist’s apartment in Le Samourai, The Conversation and American Gigolo. A recent review of a Michael Moorcock novel described his work as “so rich, each work he produces forms part of a complex echo chamber, singing beautifully into both the past and future of his own mythologies” (Warner 2009). -

Cervantes and the Spanish Baroque Aesthetics in the Novels of Graham Greene

TESIS DOCTORAL Título Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene Autor/es Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Director/es Carlos Villar Flor Facultad Facultad de Letras y de la Educación Titulación Departamento Filologías Modernas Curso Académico Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene, tesis doctoral de Ismael Ibáñez Rosales, dirigida por Carlos Villar Flor (publicada por la Universidad de La Rioja), se difunde bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Unported. Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden solicitarse a los titulares del copyright. © El autor © Universidad de La Rioja, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2016 publicaciones.unirioja.es E-mail: [email protected] CERVANTES AND THE SPANISH BAROQUE AESTHETICS IN THE NOVELS OF GRAHAM GREENE By Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Supervised by Carlos Villar Flor Ph.D A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At University of La Rioja, Spain. 2015 Ibáñez-Rosales 2 Ibáñez-Rosales CONTENTS Abbreviations ………………………………………………………………………….......5 INTRODUCTION ...…………………………………………………………...….7 METHODOLOGY AND STRUCTURE………………………………….……..12 STATE OF THE ART ..……….………………………………………………...31 PART I: SPAIN, CATHOLICISM AND THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN (CATHOLIC) NOVEL………………………………………38 I.1 A CATHOLIC NOVEL?......................................................................39 I.2 ENGLISH CATHOLICISM………………………………………….58 I.3 THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN -

Introduction

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. Graham Greene (ed.), The Old School (London: Jonathan Cape, 1934) 7-8. (Hereafter OS.) 2. Ibid., 105, 17. 3. Graham Greene, A Sort of Life (London: Bodley Head, 1971) 72. (Hereafter SL.) 4. OS, 256. 5. George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier (London: Gollancz, 1937) 171. 6. OS, 8. 7. Barbara Greene, Too Late to Turn Back (London: Settle and Bendall, 1981) ix. 8. Graham Greene, Collected Essays (London: Bodley Head, 1969) 14. (Hereafter CE.) 9. Graham Greene, The Lawless Roads (London: Longmans, Green, 1939) 10. (Hereafter LR.) 10. Marie-Franc;oise Allain, The Other Man (London: Bodley Head, 1983) 25. (Hereafter OM). 11. SL, 46. 12. Ibid., 19, 18. 13. Michael Tracey, A Variety of Lives (London: Bodley Head, 1983) 4-7. 14. Peter Quennell, The Marble Foot (London: Collins, 1976) 15. 15. Claud Cockburn, Claud Cockburn Sums Up (London: Quartet, 1981) 19-21. 16. Ibid. 17. LR, 12. 18. Graham Greene, Ways of Escape (Toronto: Lester and Orpen Dennys, 1980) 62. (Hereafter WE.) 19. Graham Greene, Journey Without Maps (London: Heinemann, 1962) 11. (Hereafter JWM). 20. Christopher Isherwood, Foreword, in Edward Upward, The Railway Accident and Other Stories (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972) 34. 21. Virginia Woolf, 'The Leaning Tower', in The Moment and Other Essays (NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1974) 128-54. 22. JWM, 4-10. 23. Cockburn, 21. 24. Ibid. 25. WE, 32. 26. Graham Greene, 'Analysis of a Journey', Spectator (September 27, 1935) 460. 27. Samuel Hynes, The Auden Generation (New York: Viking, 1977) 228. 28. ]WM, 87, 92. 29. Ibid., 272, 288, 278. -

Star Spangled Rhythm À¸™À¸±À¸À¹À¸ªà

Star Spangled Rhythm นัà¸à ¹à ¸ªà¸”ง รายà¸à ¸²à¸£ (Cast) Albert Dekker https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/albert-dekker-2092070/movies Katherine Dunham https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/katherine-dunham-272637/movies Paulette Goddard https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/paulette-goddard-95050/movies Barbara Pepper https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/barbara-pepper-2884013/movies Frances Gifford https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/frances-gifford-3080821/movies Preston Sturges https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/preston-sturges-546204/movies Mary Martin https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/mary-martin-285483/movies Victor Moore https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/victor-moore-2474547/movies Alan Ladd https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/alan-ladd-346280/movies Cecil Kellaway https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/cecil-kellaway-891104/movies Dick Powell https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/dick-powell-287977/movies Jerry Colonna https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/jerry-colonna-923250/movies Eddie Dew https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/eddie-dew-1282757/movies Ernest Truex https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/ernest-truex-776601/movies Virginia Brissac https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/virginia-brissac-3560666/movies James Millican https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/james-millican-3161279/movies Irving Bacon https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/irving-bacon-3116093/movies Edgar Dearing https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/edgar-dearing-5337205/movies Edward Fielding https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/edward-fielding-16064063/movies Lynne Overman https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/lynne-overman-3269588/movies Ellen Drew https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/ellen-drew-275764/movies Veronica Lake https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/veronica-lake-84232/movies Dona Drake https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/actors/dona-drake-3035962/movies Cecil B. -

Graham Greene and the Idea of Childhood

GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD APPROVED: Major Professor /?. /V?. Minor Professor g.>. Director of the Department of English D ean of the Graduate School GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD THESIS Presented, to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Martha Frances Bell, B. A. Denton, Texas June, 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. FROM ROMANCE TO REALISM 12 III. FROM INNOCENCE TO EXPERIENCE 32 IV. FROM BOREDOM TO TERROR 47 V, FROM MELODRAMA TO TRAGEDY 54 VI. FROM SENTIMENT TO SUICIDE 73 VII. FROM SYMPATHY TO SAINTHOOD 97 VIII. CONCLUSION: FROM ORIGINAL SIN TO SALVATION 115 BIBLIOGRAPHY 121 ill CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A .narked preoccupation with childhood is evident throughout the works of Graham Greene; it receives most obvious expression its his con- cern with the idea that the course of a man's life is determined during his early years, but many of his other obsessive themes, such as betray- al, pursuit, and failure, may be seen to have their roots in general types of experience 'which Green® evidently believes to be common to all children, Disappointments, in the form of "something hoped for not happening, something promised not fulfilled, something exciting turning • dull," * ar>d the forced recognition of the enormous gap between the ideal and the actual mark the transition from childhood to maturity for Greene, who has attempted to indicate in his fiction that great harm may be done by aclults who refuse to acknowledge that gap. -

The Broken Ideals of Love and Family in Film Noir

1 Murder, Mugs, Molls, Marriage: The Broken Ideals of Love and Family in Film Noir Noir is a conversation rather than a single genre or style, though it does have a history, a complex of overlapping styles and typical plots, and more central directors and films. It is also a conversation about its more common philosophies, socio-economic and sexual concerns, and more expansively its social imaginaries. MacIntyre's three rival versions suggest the different ways noir can be studied. Tradition's approach explains better the failure of the other two, as will as their more limited successes. Something like the Thomist understanding of people pursuing perceived (but faulty) goods better explains the neo- Marxist (or other power/conflict) model and the self-construction model. Each is dependent upon the materials of an earlier tradition to advance its claims/interpretations. [Styles-studio versus on location; expressionist versus classical three-point lighting; low-key versus high lighting; whites/blacks versus grays; depth versus flat; theatrical versus pseudo-documentary; variety of felt threat levels—investigative; detective, procedural, etc.; basic trust in ability to restore safety and order versus various pictures of unopposable corruption to a more systemic nihilism; melodramatic vs. colder, more distant; dialogue—more or less wordy, more or less contrived, more or less realistic; musical score—how much it guides and dictates emotions; presence or absence of humor, sentiment, romance, healthy family life; narrator, narratival flashback; motives for criminality and violence-- socio- economic (expressed by criminal with or without irony), moral corruption (greed, desire for power), psychological pathology; cinematography—classical vs. -

Altering Environments Affect the Psychological State Caitlin Hesketh SUNY Geneseo

Proceedings of GREAT Day Volume 2010 Article 24 2011 Altering Environments Affect the Psychological State Caitlin Hesketh SUNY Geneseo Follow this and additional works at: https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/proceedings-of-great-day Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Hesketh, Caitlin (2011) "Altering Environments Affect the Psychological State," Proceedings of GREAT Day: Vol. 2010 , Article 24. Available at: https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/proceedings-of-great-day/vol2010/iss1/24 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the GREAT Day at KnightScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of GREAT Day by an authorized editor of KnightScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hesketh: Altering Environments Affect the Psychological State Altering Environments Affect the Psychological State Submitted by: Caitlin Hesketh During the 1950s, the decade subsequent to the At this point in the novel Graham does publishing of Eric Ambler’s Journey into Fear, not see the necessity of taking action to save his Graham Greene’s, The Ministry of Fear, and life. He cannot comprehend how closely he is Henry Green’s, Back, a new subfield of tied to the inner workings of the war and states: Psychology was established: Environmental Nonsense, Kopeikin! You must be out of Psychology. This subfield “studies the your senses. What conceivable reason relationship between environments and human could anyone have for wanting to kill behavior and how they affect one another” me? I’m the most harmless man alive. (Conaway). These characters’ actions, thoughts, (Ambler, 42) and beliefs undergo alteration due to the It is clear at this point in the novel that physical or emotional setting that they are in. -

November 2019

MOVIES A TO Z NOVEMBER 2019 D 8 1/2 (1963) 11/13 P u Bluebeard’s Ten Honeymoons (1960) 11/21 o A Day in the Death of Donny B. (1969) 11/8 a ADVENTURE z 20,000 Years in Sing Sing (1932) 11/5 S Ho Booked for Safekeeping (1960) 11/1 u Dead Ringer (1964) 11/26 S 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) 11/27 P D Bordertown (1935) 11/12 S D Death Watch (1945) 11/16 c COMEDY c Boys’ Night Out (1962) 11/17 D Deception (1946) 11/19 S –––––––––––––––––––––– A ––––––––––––––––––––––– z Breathless (1960) 11/13 P D Dinky (1935) 11/22 z CRIME c Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948) 11/1 Bride of Frankenstein (1935) 11/16 w The Dirty Dozen (1967) 11/11 a Adventures of Don Juan (1948) 11/18 e The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) 11/6 P D Dive Bomber (1941) 11/11 o DOCUMENTARY a The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) 11/8 R Brief Encounter (1945) 11/15 Doctor X (1932) 11/25 Hz Alibi Racket (1935) 11/30 m Broadway Gondolier (1935) 11/14 e Doctor Zhivago (1965) 11/20 P D DRAMA c Alice Adams (1935) 11/24 D Bureau of Missing Persons (1933) 11/5 S y Dodge City (1939) 11/8 c Alice Doesn’t Live Here Any More (1974) 11/10 w Burn! (1969) 11/30 z Dog Day Afternoon (1975) 11/16 e EPIC D All About Eve (1950) 11/26 S m Bye Bye Birdie (1963) 11/9 z The Doorway to Hell (1930) 11/7 S P R All This, and Heaven Too (1940) 11/12 c Dr. -

Blackface Behind Barbed Wire

Blackface Behind Barbed Wire Gender and Racial Triangulation in the Japanese American Internment Camps Emily Roxworthy THE CONFUSER: Come on, you can impersonate a Negro better than Al Jolson, just like you can impersonate a Jap better than Marlon Brando. [...] Half-Japanese and half-colored! Rare, extraordinary object! Like a Gauguin! — Velina Hasu Houston, Waiting for Tadashi ([2000] 2011:9) “Fifteen nights a year Cinderella steps into a pumpkin coach and becomes queen of Holiday Inn,” says Marjorie Reynolds as she applies burnt cork to her face [in the 1942 filmHoliday Inn]. The cinders transform her into royalty. — Michael Rogin, Blackface, White Noise (1996:183) During World War II, young Japanese American women performed in blackface behind barbed wire. The oppressive and insular conditions of incarceration and a political climate that was attacking the performers’ own racial status rendered these blackface performances somehow exceptional and even resistant. 2012 marked the 70th anniversary of the US government’s deci- sion to evacuate and intern nearly 120,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast. The mass incarceration of Issei and Nisei in 1942 was justified by a US mindset that conflated every eth- nic Japanese face, regardless of citizenship status or national allegiance, with the “face of the TDR: The Drama Review 57:2 (T218) Summer 2013. ©2013 New York University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology 123 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/DRAM_a_00264 by guest on 01 October 2021 enemy.”1 While this racist reading of the Japanese (American) face has been widely condemned in the intervening 70 years, the precarious semiotics of Japanese ethnicity are remarkably pres- ent for contemporary observers attempting to apprehend the relationship between a Japanese (American) face and blackface.