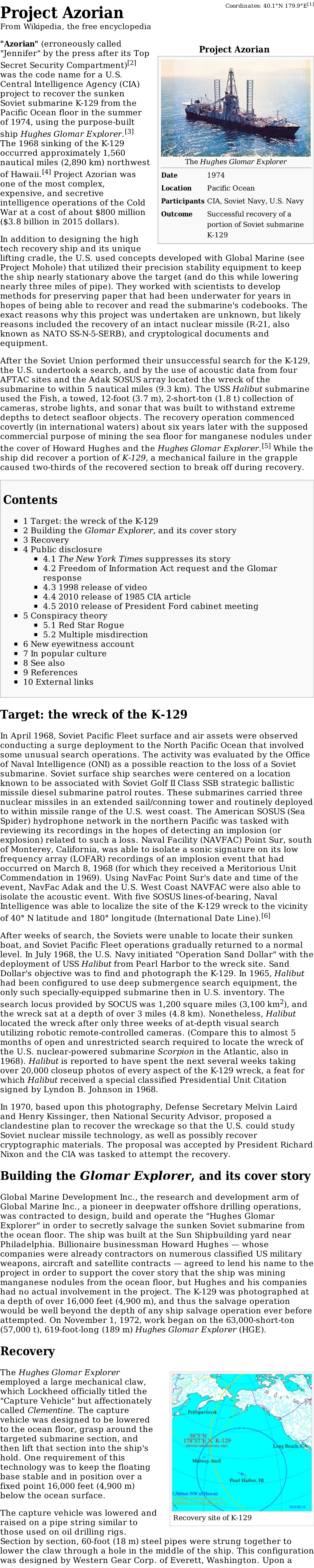

Project Azorian Coordinates: 40.1°N 179.9°E from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Princeton Diplomatic Invitational 2020

Top Secret // ORCON // JENNIFER Princeton Diplomatic Invitational 2020 Project Azorian Chairs: Kris Hristov & Scott Overbey Crisis Director: Gabriel Peña 1 Top Secret // ORCON // JENNIFER Top Secret // ORCON // JENNIFER CONTENTS CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................... 2 LETTERS FROM THE STAFF ......................................................................................... 3 COMMITTEE DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................... 5 24 hour format .................................................................................................................... 6 Committee Sessions 1&2 ................................................................................................... 6 Committee Session 3 through 6 ........................................................................................ 6 CURRENT STATUS ............................................................................................................ 7 A Brief Summary of Nuclear Weapons ........................................................................... 7 MAD About You: Nuclear Tactics .................................................................................. 9 Rocketmen: Delivery Systems ......................................................................................... 11 The Red Banner Fleet: The Soviet Nuclear Navy ........................................................ 12 K-129 -

Ebook Download Dark Side of Camelot, the Ebook

DARK SIDE OF CAMELOT, THE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Seymour M. Hersh | 528 pages | 01 Sep 1998 | Little, Brown & Company | 9780316360678 | English | New York, United States Dark Side of Camelot, the PDF Book Time for the Grab Bag! Hersh asked me a year or two ago if I'd learned anything new; when I told him that a former C. That said, I did not like this book. Does anyone still think John F. A hero. Democracy Now. Hersh has accused the Obama administration of lying about the events surrounding the death of Osama bin Laden and disputed the claim that the Assad regime used chemical weapons on civilians in the Syrian Civil War. Basically what happened is that those women who were arrested with young boys, children, in cases that have been recorded, the boys were sodomized, with the cameras rolling, and the worst above all of them is the soundtrack of the boys shrieking. No trivia or quizzes yet. Some of Hersh's speeches concerning the Iraq War have described violent incidents involving U. Archived from the original PDF on March 26, Friend Reviews. Retrieved September 27, Retrieved May 16, To widen my studies I also include prominent biographies and many other Kennedy tomes. Nothing in ''The Dark Side of Camelot'' gives off even a whiff of the dead-fish aroma of the trust fund for Marilyn's Mom, but Kennedy loyalists, joined by others who just don't want to know, are using Hersh's terrible misstep to dismiss what he has dug up as trifling gossip and unsupported hearsay. -

A Mechanically Marvelous Sea Saga: Plumbing the Depths of Cold War Paranoia Jack Mcguinn, Senior Editor

addendum A Mechanically Marvelous Sea Saga: Plumbing the Depths of Cold War Paranoia Jack McGuinn, Senior Editor In the summer of 1974, long before Argo, there was “AZORIAN” — the code name for a CIA gambit to recover cargo entombed in a sunk- en Soviet submarine — the K-129 — from the bottom of the Pacific Ocean. The challenge: exhume — intact — a 2,000-ton submarine and its suspicious cargo from 17,000 feet of water. HowardUndated Robard Hughes Jr. photo of a young Howard Hughes — The Soviet sub had met its end (no one ($3.7 billion in 2013 dollars),” but none entrepreneur, inventor, movie producer — whose claims to know how, and the Russians of it came out of Hughes’ pocket. Jimmy Stewart-like weren’t talking) in 1968, all hands lost, Designated by ASME in 2006 as “a appearance here belies some 1,560 nautical miles northwest of historical mechanical engineering land- the truly bizarre enigma he would later become. Hawaii. After a Soviet-led, unsuccessful mark,” the ship had an array of mechani- search for the K-129, the U.S. undertook cal and electromechanical systems with one of its own and, by the use of gath- heavy-duty applications requiring robust But now, the bad news: After a num- ered sophisticated acoustic data, located gear boxes; gear drives; linear motion ber of attempts, the ship’s “custom claw” the vessel. rack-and-pinion systems; and precision managed to sustain a firm grip on the What made this noteworthy was that teleprint (planetary, sun, open) gears. submarine, but at about 9,000 feet the U-boat was armed with nuclear mis- One standout was the Glomar’s roughly two-thirds of the (forward) hull siles. -

Who Watches the Watchmen? the Conflict Between National Security and Freedom of the Press

WHO WATCHES THE WATCHMEN WATCHES WHO WHO WATCHES THE WATCHMEN WATCHES WHO I see powerful echoes of what I personally experienced as Director of NSA and CIA. I only wish I had access to this fully developed intellectual framework and the courses of action it suggests while still in government. —General Michael V. Hayden (retired) Former Director of the CIA Director of the NSA e problem of secrecy is double edged and places key institutions and values of our democracy into collision. On the one hand, our country operates under a broad consensus that secrecy is antithetical to democratic rule and can encourage a variety of political deformations. But the obvious pitfalls are not the end of the story. A long list of abuses notwithstanding, secrecy, like openness, remains an essential prerequisite of self-governance. Ross’s study is a welcome and timely addition to the small body of literature examining this important subject. —Gabriel Schoenfeld Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute Author of Necessary Secrets: National Security, the Media, and the Rule of Law (W.W. Norton, May 2010). ? ? The topic of unauthorized disclosures continues to receive significant attention at the highest levels of government. In his book, Mr. Ross does an excellent job identifying the categories of harm to the intelligence community associated NI PRESS ROSS GARY with these disclosures. A detailed framework for addressing the issue is also proposed. This book is a must read for those concerned about the implications of unauthorized disclosures to U.S. national security. —William A. Parquette Foreign Denial and Deception Committee National Intelligence Council Gary Ross has pulled together in this splendid book all the raw material needed to spark a fresh discussion between the government and the media on how to function under our unique system of government in this ever-evolving information-rich environment. -

Final Report: National Register of Historic Places/California Register of Historical Resources Evaluation for The

Prepared for: FINAL REPORT: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES/CALIFORNIA REGISTER OF HISTORICAL RESOURCES EVALUATION FOR THE POINT SUR NAVFAC, POINT SUR Central Coast Lighthouse Keepers STATE HISTORIC PARK, CALIFORNIA P.O. Box 223014 Carmel, CA 93922 And Monterey District 2211 Garden Road Monterey, CA 93940 Prepared by: P.O. Box 721 Pacific Grove, California 93950 April 2013 Point Sur NAVFAC Final National/California Register Evaluation PAST Consultants, LLC April 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................... 1 II. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 3 Project Description..................................................................................................... 4 Project Team .............................................................................................................. 5 Organization of the Report ........................................................................................ 5 Methodology and Research Materials ...................................................................... 6 Previous Evaluations and Correspondence ............................................................... 8 Federal Guidelines for the Documentation and Historical Evaluation of Cold War Properties.................................................................................................. -

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Mandatory Declassification Review (MDR) Log, 2010-2016

Description of document: Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Mandatory Declassification Review (MDR) Log, 2010-2016 Requested date: 24-October-2016 Released date: 21-November-2016 Posted date: 12-December-2016 Source of document: Freedom of Information Act Request Information and Privacy Coordinator Central Intelligence Agency Washington, D.C. 20505 Fax: 703-613-3007 The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. Central Intelligence Agency Washington. D.C. 20505 21 November 2016 Reference: F-2017-00161 This is a final response to your 24 October 2016 Freedom of Information Act request for copies of the Mandatory Declassification Review (MDR) Log maintained by the Central Intelligence Agency. -

The Implausibility of Secrecy, 65 Hastings L.J

University of Florida Levin College of Law UF Law Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 2-1-2014 The mplI ausibility of Secrecy Mark Fenster University of Florida Levin College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub Part of the Administrative Law Commons, National Security Commons, and the Politics Commons Recommended Citation Mark Fenster, The Implausibility of Secrecy, 65 Hastings L.J. 309 (2014), available at http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub/347 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fenster_21 (M. Stevens) (Do Not Delete) 1/29/2014 6:39 PM Articles The Implausibility of Secrecy Mark Fenster Government secrecy frequently fails. Despite the executive branch’s obsessive hoarding of certain kinds of documents and its constitutional authority to do so, recent high-profile events—among them the WikiLeaks episode, the Obama administration’s infamous leak prosecutions, and the widespread disclosure by high-level officials of flattering confidential information to sympathetic reporters—undercut the image of a state that can classify and control its information. The effort to control government information requires human, bureaucratic, technological, and textual mechanisms that regularly founder or collapse in an administrative state, sometimes immediately and sometimes after an interval. Leaks, mistakes, and open sources all constitute paths out of the government’s informational clutches. -

Nixon's Wars: Secrecy, Watergate, and the CIA

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Online Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship January 2016 Nixon's Wars: Secrecy, Watergate, and the CIA Chris Collins Eastern Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: https://encompass.eku.edu/etd Part of the Defense and Security Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Collins, Chris, "Nixon's Wars: Secrecy, Watergate, and the CIA" (2016). Online Theses and Dissertations. 352. https://encompass.eku.edu/etd/352 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Online Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nixon’s Wars: Secrecy, Watergate, and the CIA By Christopher M. Collins Bachelor of Arts Eastern Kentucky University Richmond, Kentucky 2011 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Eastern Kentucky University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December, 2016 Copyright © Christopher M. Collins, 2016 All rights reserved ii Acknowledgments I could not have completed this thesis without the support and generosity of many remarkable people. First, I am grateful to the entire EKU history department for creating such a wonderful environment in which to work. It has truly been a great experience. I am thankful to the members of my advisory committee, Dr. Robert Weise, Dr. Carolyn Dupont, and especially Dr. Thomas Appleton, who has been a true friend and mentor to me, and whose kind words and confidence in my work has been a tremendous source of encouragement, without which I would not have made it this far. -

2010 Annual Report

The National Security Archive The George Washington University Phone: 202/994-7000 Gelman Library, Suite 701 Fax: 202/994-7005 2130 H Street, N.W. www. nsarchive.org Washington, D.C. 20037 [email protected] Annual Report for 2010 The following statistics provide a performance index of the Archive‘s work in 2010: Freedom of Information and declassification requests filed – 1,482 Freedom of Information and declassification appeals filed – 219 Pages of U.S. government documents released as the result of Archive requests – 70,759 including such newsmaking revelations as the Taliban‘s use of Pakistani tribal areas to regroup after the 2001 U.S. invasion of Afghanistan, leading directly to their resurgence in 2005; the Colombian military‘s execution of guerrilla prisoners and the Palace of Justice cafeteria staff during the 1985 hostage tragedy in Bogota; the CIA‘s coverup of the limited success of the 1974 Glomar Explorer attempt to raise a sunken Soviet submarine; President Nixon‘s consideration of nuclear attacks against North Korea in 1969; President Clinton‘s 1999 correspondence with Iranian president Khatami about the Khobar Towers bombing in Saudi Arabia. Pages of declassified documents delivered to publisher – 25,092 in two reference collections: Colombia and the United States: Political Violence, Narcotics, and Human Rights, 1948-2010; and The United States and the Two Koreas (1969-2000). Declassified documents delivered to truth commissions and human rights investigators – 21,560 documents to the Museum of Memory and Human Rights in Santiago, Chile as part of its permanent commemoration of human rights violations committed during the Pinochet dictatorship; 3,360 documents to Uruguay‘s Universidad de la Republica for use by researchers; 200 documents to Argentina‘s Federal Oral Criminal Tribunal No. -

Glomar” Is Such an Apt Name for Preemptive Denial of FOIA Claims1

Case 1:18-cv-02048-TSC Document 18-3 Filed 02/28/19 Page 1 of 2 Exhibit B 1 Why “Glomar” is such an apt name for preemptive denial of FOIA claims1 The invocation of a so-called Glomar response to Freedom of Information Act requests, though usually inappropriate, is oddly symbolic. The USNS Hughes Glomar Explorer was a ship built in 1971 under CIA’s Project Azorian to recover the Soviet submarine K-129 which sank in 1968. The CIA spent $1.68 billion ($10.63 billion in current value) in a no-bid contract to build the massive, sole- purpose ship. Glomar Explorer’s cover story was that it would “extract manganese nodules” from the ocean floor. But the nautical boondoggle ultimately failed. During an attempt to winch the K-129 to the surface, the submarine broke up, and the most-sought items such as codebooks and nuclear missiles were lost. The vessel was subsequently reflagged the GSF Explorer and roamed the seas like an albatross, searching for a buyer and a new purpose. The massive sums of taxpayer dollars that paid to build and sail the vessel were never recouped and in 2015 it was announced the ship would be sold for scrap. Ever since “boilerplate” refusals to properly respond to public interest FOIA requests about publicly known programs became known as “Glomar” responses. Essential details of Project Azorian were ultimately disclosed in the news media, starting with reporter Jack Anderson in the mid-1970's who claimed, "Navy experts have told us that the sunken sub contains no real secrets and that the project, therefore, is a waste of the taxpayers’ money."2 1 Excerpt from ECF 13-1, FOIA Case 1:15-cv-01431-TSC, pages 2-3 2 Robarge, David (March 2012). -

Project Azorian

doi:10.3723/ut.30.055 International Journal of the Society for Underwater Technology, Vol 30, No 1, p 55–56, 2011 Project Azorian: For the United States there ‘special operations’ nuclear sub- was the opportunity to discover marine USS Halibut towing prim- Book Review The CIA and the first-hand more about Soviet itive underwater cameras in the nuclear warhead and missile tech- deep ocean, pictures were Raising of the nology and to obtain vital code obtained which showed that at books and cryptographic devices. least one of the K-129 ’s R-21 K-129 In addition, the United States nuclear-tipped missiles remained had serious concerns that K-129 in place. Norman Polmar and could have been a ‘rogue’ sub- The United States intelligence Michael White marine that had attempted an community was able (until later unauthorised missile launch on compromised by spies) to con- Published by Naval Institute the Hawaiian islands. The only ceal its discovery from the Soviets Press, Annapolis, Maryland way to know for sure would be to and commission the construction raise part, or all, of the wreck of of a supposed ‘seabed mining’ Hardback edition, 2010 the K-129 from some 5000m ship, the Glomar Explorer, with help ISBN 978 1 59114 690 2 depth – in an era before the pro- from Howard Hughes. The 238 pages including Annexes duction of deep-ocean remotely Glomar Explorer was equipped operated vehicles (ROV), or with a giant claw intended to high-resolution seafloor mapping scoop the remains of the K-129 When I give talks to the general systems. -

Acta Asiatica Varsoviensia No. 32 Was Granted a Financial Support of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education, Grant No

Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures Polish Academy of Sciences ACTA ASIATICA VARSOVIENSIA No. 32 Warsaw 2019 Editor-in-Chief Board of Advisory Editors NICOLAS LEVI ABDULRAHMAN AL-SALIMI MING-HUEI LEE Editorial Assistant IGOR DOBRZENIECKI THUAN NGUYEN QUANG KENNETH OLENIK English Text Consultant JOLANTA JO HARPER SIERAKOWSKA-DYNDO Subject Editor BOGDAN SKŁADANEK KAROLINA ZIELIŃSKA HAIPENG ZHANG Acta Asiatica Varsoviensia no. 32 was granted a financial support of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education, grant no. 709/P-DUN/2019 © Copyright by Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw 2019 PL ISSN 0860–6102 eISSN 2449–8653 ISBN 978–83–7452–091–1 Contents ARTICLES: • ROBERT WINSTANLEY-CHESTERS: Forests in Pyongyang’s web of life: trees, history and politics in North Korea ............................. 5 • LARISA ZABROVSKAIA: Russia’s position on Korean conceptions of reunification ................................................................... 25 • BILL STREIFER, IREK SABITOV: Vindicating the USS Swordfish ............................................................................................... 43 • NATALIA KIM: Discourse on motherhood and childrearing: the role of women in North Korea ......................................................... 61 • ROSA MARIA RODRIGUO CALVO: Parallel development and humanitarian crisis in North Korea, a case of extremes .................. 81 • NICOLAS LEVI: A historical approach to the leadership of the Organisation and Guidance Department