SRI LANKA DISPLACED POPULATION by DISTRICT GIS Unit Sri Lanka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beautification and the Embodiment of Authenticity in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2014-2015: Penn Humanities Forum Undergraduate Color Research Fellows 5-2015 Ornamenting Fingernails and Roads: Beautification and the Embodiment of Authenticity in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka Kimberly Kolor University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2015 Part of the Asian History Commons Kolor, Kimberly, "Ornamenting Fingernails and Roads: Beautification and the Embodiment of uthenticityA in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka" (2015). Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2014-2015: Color. 7. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2015/7 This paper was part of the 2014-2015 Penn Humanities Forum on Color. Find out more at http://www.phf.upenn.edu/annual-topics/color. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2015/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ornamenting Fingernails and Roads: Beautification and the Embodiment of Authenticity in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka Abstract In post-conflict Sri Lanka, communal tensions continue ot be negotiated, contested, and remade. Color codes virtually every aspect of daily life in salient local idioms. Scholars rarely focus on the lived visual semiotics of local, everyday exchanges from how women ornament their nails to how communities beautify their open—and sometimes contested—spaces. I draw on my ethnographic data from Eastern Sri Lanka and explore ‘color’ as negotiated through personal and public ornaments and notions of beauty with a material culture focus. I argue for a broad view of ‘public,’ which includes often marginalized and feminized public modalities. This view also explores how beauty and ornament are salient technologies of community and cultural authenticity that build on histories of ethnic imaginaries. -

A Case Study of Kalmunai Municipal Area in Ampara District

Available online at www.worldscientificnews.com WSN 59 (2016) 35-51 EISSN 2392-2192 Emerging challenges of urbanization: a case study of Kalmunai municipal area in Ampara district M. B. Muneera* and M. I. M. Kaleel** Department of Geography, Faculty of Arts and Culture South Eastern University of Sri Lanka, Sri Lanka *,**E-mail address: [email protected] , [email protected] ABSTRACT Urban population refers to people living in urban areas as defined by national statistical offices. It is calculated using World Bank population estimates and urban ratios from the United Nations World Urbanization Prospects. Aggregation of urban and rural population may not add up to total population because of different country coverages. The study based on the Kalmunai MC area and the main objective of this study is to identify the emerging challenges of urbanization in the study area. The study used the methodologies are primary data collection as questionnaire, interview, observation and the secondary data collection and SWOT analysis to made for getting the better result. The study finds that the SWOT analysis process provided a number of results and ideas for future planning. Collecting the results around themes has highlighted the breadth of ideas within KMC. A number of common issues emerged which require immediate action and clearly relate to developing KMC as a resilient urban. However, to generate energy requires heap quantities of plastic wastage and as a result of the process a byproduct of methane will be produced. Nevertheless, this process is not much financially viable as the quantities are limited in Sri Lanka. Control of water pollution is the demand of the day cooperation of the common man, social organizations, natural government and non - governmental organizations; is required for controlling water pollution through different curative measures. -

Post-Tsunami Reconstruction Needs Assessment Northeast Planning and Development Secretariat

Post-Tsunami Reconstruction Needs Assessment for the NorthEast (NENA) Planning and Development Secretariat Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam January 2005 Contents Page 1 Introduction 1 2 Background 2 3 Overview 4 4 Needs Assessment- Sectoral Summaries 7 4.1 Resettlement 7 4.2 Housing 8 4.3 Health 11 4.4 Education 13 4.5 Roads & Bridges 15 4.6 Livelihood, Employment & Micro Finance 17 4.7 Fisheries 18 4.8 Agriculture 21 4.9 Tourism, Culture and Heritage 22 4.10 Environment 23 4.11 Water & Sanitation 25 4.12 Telecommunication 27 4.13 Power 28 4.14 Public Sector Infrastructure 29 4.15 Urban Development 29 4.16 Cooperative Movement 30 4.17 Coastal Protection 30 4.18 Local Government 32 4.19 Disaster Preparedness 33 5.0 Indicative Costs 34 Annex 1 Acronyms 35 Annex 2 Needs Assessment Team 36 Annex 3 Next to Needs 38 Post Tsunami Reconstruction – NorthEast Needs Assessment(NENA) Planning and Development Secretariat/LTTE 2 Post-Tsunami Reconstruction Needs Assessment for the NorthEast 1.0 Introduction The tsunami that struck the coast of Sri Lanka on 26th December 2004 is by far the worst natural disaster the country has experienced in living memory. The Northeast of the island took the greatest and direct impact and the full force of the fierce waves changing the lives of people and the landscape along more than 800 km of the coastline for ever. Within a few devastating minutes, tens of thousands of lives were lost, and billions of dollars worth of infrastructure, equipment and materials were shattered or washed to the seas; thousands more were wounded. -

Name List of Sworn Translators in Sri Lanka

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Sworn Translator Appointments Details 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages November Rasheed.H.M. 76,1st Cross Jaffna Sinhala - Tamil Street,Ninthavur 12 Sinhala - English Sivagnanasundaram.S. 109,4/2,Collage Colombo Sinhala - Tamil Street,Kotahena,Colombo 13 Sinhala - English Dreyton senaratna 45,Old kalmunai Baticaloa Sinhala - Tamil Road,Kalladi,Batticaloa Sinhala - English 1977 November P.M. Thilakarathne Chilaw 0777892610 Sinhala - English P.M. Thilakarathne kirimathiyana East, Chilaw English - Sinhala Lunuwilla. S.D. Cyril Sadanayake 26, De silva Road, 331490350V Kalutara 0771926906 English - Sinhala Atabagoda, Panadura 1979 July D.A. vincent Colombo 0776738956 English - Sinhala 1 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 1992 July H.M.D.A. Herath 28, Kolawatta, veyangda 391842205V Gampaha 0332233032 Sinhala - English 2000 June W.A. Somaratna 12, sanasa Square, Gampaha 0332224351 English - Sinhala Gampaha 2004 July kalaichelvi Niranjan 465/1/2, Havelock Road, Colombo English - Tamil Colombo 06 2008 May saroja indrani weeratunga 1E9 ,Jayawardanagama, colombo English - battaramulla Sinhala - 2008 September Saroja Indrani Weeratunga 1/E/9, Jayawadanagama, Colombo Sinhala - English Battaramulla 2011 July P. Maheswaran 41/B, Ammankovil Road, Kalmunai English - Sinhala Kalmunai -2 Tamil - K.O. Nanda Karunanayake 65/2, Church Road, Gampaha 0718433122 Sinhala - English Gampaha 2011 November J.D. Gunarathna "Shantha", Kalutara 0771887585 Sinhala - English Kandawatta,Mulatiyana, Agalawatta. 2 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 2012 January B.P. Eranga Nadeshani Maheshika 35, Sri madhananda 855162954V Panadura 0773188790 English - French Mawatha, Panadura 0773188790 Sinhala - 2013 Khan.C.M.S. -

Provincial Roads Project

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: 48445 - LK PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A Public Disclosure Authorized PROPOSED.CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 66.1 MILLION (US$105 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA FOR A Public Disclosure Authorized PROVINCIAL ROADS PROJECT November 11,2009 Sustainable Development Unit Sri Lanka Country Management Unit South Asia Region This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the Public Disclosure Authorized performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective October 3 1,2009) Currency Unit = Rupees 114.25Rupees = US$1 1.58989US$ = SDR 1 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 ADB Asian Development Bank MLGPC Ministry of Local Government and Provincial Councils AGAOA Association of Government MOT Ministry of Transport Accounts Organizations of Asia AG Auditor General MOFP Ministry of Finance and Planning BP Bank Procedure NCP North Central Province CAS Country Assistance Strategy NEA National Environmental Act CEA Central Environmental NPRDD Northern Provincial Road Authority Development Department CFAA Country Financial NPV Net Project Value EPRDD Eastern Provincial Road PMR Project Management Report Development Department EAMF Environmental Assessment PDO Project Development Objective and Management Framework FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Environmental Management PRP I EMPs I Plans Economic Internal rate of RDA Road Development Authority I 1 Return FM Financial Management RFA Reimbursable Forei n Aid FRs Financial Regulations ROW Right Of Way I ~ 1 GAAP I Governance and RIJ Resettlement Plan Accountability Action Plan GOSL Government of Sri Lanka RSAP HDM4 Highway Design and SEPSA Management Version 4 HIV/AIDS Human Immunodeficiency SBD Virus/ Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome . -

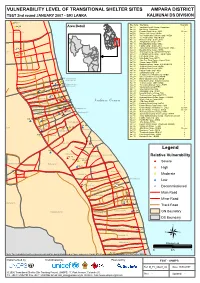

VULNERABILITY LEVEL of TRANSITIONAL SHELTER SITES AMPARA DISTRICT TSST 2Nd Round JANUARY 2007 - SRI LANKA KALMUNAI DS DIVISION

VULNERABILITY LEVEL OF TRANSITIONAL SHELTER SITES AMPARA DISTRICT TSST 2nd round JANUARY 2007 - SRI LANKA KALMUNAI DS DIVISION *#Kal_16 Site Code Site Name Total Vul. Kal_02 *# Area Detail Kal_01 Varathan RiceMill Camp - Samaritans 1 Kal_02 Bar Camp - Samaritan 1 Periyaneelavanai 01B Kal_04 Ponniah Road Camp - WDC Decom Kal_06 Vishnu Kovil Camp - NHDA 1 Kal_07 VC Road Muslim Division Camp - NHDA 1 Kal_08 V.C.Road Camp - WDC/NHDA 1 Kal_12 Moossa Camp - Sewa Lanka 2 Kal_15 Sanganthurai Camp - JVP 1 Kal_16 Masjidul Aqbar Camp - WDC 1 Kal_17 Hudha Camp - Sewa Lanka 1 Kal_04 Kal_18 Aqbar Jummah Mosque Road Camp - WDC 3 0* Kal_19 Masjidul Aqbar Camp - NHDA 2 ai 01A Kal_20 S.M.Road Camp - UNHCR/EHED/FCE 2 *#Kal_01 Kal_21 Al-Manar Central Camp - FORUT/WDC 1 Kal_22 Hijra Road Camp - JVP 2 Kal_23 Hijra Road Camp -MFCD 2 Kal_24 Sam Sum Road Camp - Islamic Relief 1 Kal_25 Shums Camp - EHED 2 Kal_26 Maqbooliya Lane Camp - EHED/UNHCR 2 Kal_27 Al-Minah Road Camp - NHDA 1 Kal_28 Al-Minan Road Camp - WDC 1 Kal_30 Hajiyar Road Camp - WDC 1 Kal_31 Sahanthura Camp - JVP 2 Kal_33 Sellappa Cross Road Camp - EHED 1 Kal_34 Valluvar(AI-Minan Camp)-EHED 2 Kal_17 Kal_12 Periyaneelavanai Kal_35 Maha Vidyalaya Camp - EHED 2 *# Muslim Sec.02 Kal_07 *# Kal_37 Khali Kovil Camp - NHDA/Sevalanka 2 *# *# *# Kal_38 Thathan Camp - MSF / EHED 1 Kal_06 Periyaneelavanai Kal_39 Thiroufathy Amman Camp - EHED 1 Kal_08 Muslim Sec.01 Kal_68 Kal_40 Vipulananda Camp-EHED 1 Periyaneelavanai 02 Kal_69 Kal_20 Kal_41 Visuvasikal Illam Camp 1 *# Kal_15 *# Kal_19 *# Kal_27*# *# *# Kal_43 -

JNSF March 2010 SC 1

J.Natn.Sci.Foundation Sri Lanka 2010 38 (1): 59-64 SHORT COMMUNICATION Wave record and flow regimes of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami in Sri Lanka Ananda Gunatilaka 10, Thumbovila, Piliyandala. Submitted: 10 May 2009; Accepted: 17 July 2009 Abstract: Tsunami waves that impacted upon the coastline (including Sri Lanka) recorded water level variations over of Sri Lanka on the 26 th December 2004 were investigated several days 2. The shoaling waves generated a complex with respect to their hydrodynamic interactions and resulting flow regime, with extensive inundation of the low coastal complex flow regimes. Field surveys showed that a large island plain and deposited a sand-sheet 2-22 cm thick over an with a narrow and steep continental shelf was subjected to area of ~120-140 km 2. The lost and unaccounted for lives destructive waves, which swept around a 900 km swathe of exceeded 39,000 in Sri Lanka, with over half a million coastline from the eastern seaboard (facing the seismic source in Sumatra) to the western or shadow side with comparable people being displaced. Property and infrastructure magnitude and intensity. Waves impacted the coastline directly damage was estimated at ~ US$ 2 billion. Around (orthogonally) and were also reflected and refracted according 4 million people inhabit a 1 km wide coastal zone. to the geomorphology of the coastline. Three waves of different magnitude and competence inundated the coastal plain as far as An international tsunami survey team (ITST) made 2 km inland in about four hours. The maximum wave heights and a rapid four day survey of selected coastal areas within run-up elevations exceeded 12 m. -

Abdul Majeed Mohamed Navaz; Date Of

DR. ABDUL MAJEED MOHAMED NAVAZ 264/1, Maccamady Road, Maruthamunai, kalmunai, Sri Lanka e-mail: [email protected]/ [email protected] +94 718200513 (mobile), +94 672220863 (Home) CAREER OBJECTIVE: TO BE AN ACADEMIC ADMINISTRATOR WITH A FOCUS ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT. PERSONAL DETAILS Full Name : Abdul Majeed Mohamed Navaz; Date of Birth : 28 July 1969 Address : 264/1, Maccamady Road, Maruthamunai, Kalmunai, Sri Lanka T/Phone : +94 672220863 (Residence) Mobile : +94 718200513 Present Post Senior Lecturer –I (Head of the Department) Official address : Department of English Language Teaching South Eastern University of Sri Lanka, University Park, Oluvil, Sri Lanka. Official Phone : +94 672255179 Email : [email protected] Alternative email : [email protected] Nationality : Sri Lankan Civil Status : Married Present Assignment: Head of the department and Coordinator for BA TESL (Teaching English as a Second Language) special degree. ACADEMIC QUALIFICATIONS: PhD in Applied Linguistics/TESOL (Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages) at University of Nottingham, UK, November 2007 - May 2012. Certificate in TESOL, University of Oregon, USA (Online course), 2012 MA in Linguistics (English), University of Kelaniya, 2001 - February 2002. One year Programme (Subjects: Applied Linguistics, Phonetics, Syntax, Communication Disabilities, Morphology, and Historical Linguistics) 1 Postgraduate Diploma in Teaching English Language and Literature, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Distinction Pass (batch top) 2000 - September 2002. B.Sc. Agric Science (Hons.); University of Peradeniya, English Medium, Second Class; 1991 - December 1995, Majoring in Agric Extension. PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATIONS: English Teacher appointed on MERIT basis by the department of Education in 1990. EXPERIENCE: English Assistant Teacher, Dept. of Education, Secondary level: 1990 - 1997. -

Eastern Province

Resettlement Due Diligence Report June 2017 SRI: Second Integrated Road Investment Program Eastern Province Prepared by Road Development Authority, Ministry of Higher Education and Highways for the Government of Sri Lanka and the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 30 May 2017) Currency unit – Sri Lanka Rupee (SLRl} SLR1.00 = $ 0.00655 $1.00 = Rs 152.63 ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank DSD - Divisional Secretariat Division DS - Divisional Secretariat EP - Eastern Province EPL - Environmental Protection License DDR - Due Diligence Report FGD - Focus Group Discussion GDP - Gross Domestic Production GoSL - Government of Sri Lanka GN - Grama Niladari GND - Grama Niladari Division GRC - Grievance Redress Committee GSMB - Geological Survey and Mines Bureau HH - Household iRoad - Integrated Road Investment Program iRoad 2 - Second Integrated Road Investment Program IR - Involuntary Resettlement MoHEH - Ministry of Higher Education and Highways NWS&DB - National Water Supply and Drainage Board OFC - Other Field Crops PS - Pradeshiya Sabha PPE - Personal Protective Equipment’s RDA - Road Development Authority RF - Resettlement Framework ROW - Right of Way SAPE - Survey and Preliminary Engineering SLR - Sri Lankan Rupees This resettlement due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

Tsunami Foreword Layout

AFTER THE TSUNAMI Rapid Environmental Assessment United Nations Environment Programme CONTENTS Foreword 4 Executive Summary 6 Indonesia 16 Thailand 36 Sri Lanka 56 Maldives 76 Seychelles 96 Yemen 112 Somalia 126 Acronyms 138 Contributors 140 2 Maruthamunai, Sri Lanka. Minhaz Haque, aged 15, stands in the rain near his destroyed house in Maruthamunai village, eastern Sri Lanka. He says there is nothing left, not even the foundation, as if the house was never there. © Shehzad Noorani/Still Pictures “...there is nothing left, not even the foundation, as if the house was never there...” 3 FOREWORD by Klaus Toepfer Executive Director UNEP Although several weeks have passed since the Asian tsunami devastated coastal communities in 12 countries around the Indian Ocean, we are still struggling to comprehend the magnitude of the human losses. The suffering and destruction that was left in the tsunami’s wake have prompted an unprecedented global response. Determined and resilient local communities, with help from national and international organizations and governments, have mobilized relief and started recovery. Now, as attention turns to reconstruction, the focus has changed to look at the underlying issues and plan for sustainable re- development. UNEP’s mission in this context is clear: to provide and coordinate environmental expertise that can rapidly assess the extent of damage to ecosystems and environmental infrastructure; to identify, and bring to the international community’s immediate attention, urgent environmental risks; and to ensure that the environment is fully integrated into the region’s reconstruction and development agenda. In a part of the world where tourism, fisheries and agriculture form the economic base, the protection of ecosystems and the sound management of natural resources are crucial to the region’s development. -

Conflict, Coastal Vulnerability, and Resiliency in Tsunami-Affected Communities of Sri Lanka”, in Tsunami Recovery in Sri Lanka: Ethnic and Regional Dimensions, M

Facts on the Seashore: Conflict, Population Displacement, and Coastal Vulnerability on the Eve of the Sri Lankan Tsunami Randall Kuhn Josef Korbel School of International Studies University of Denver Abstract The concept of a complex emergency implies a negative interaction between manmade and natural disaster, yet few studies have quantified the magnitude or nature of such interactions. This study studies the impact of population movements during the Sri Lanka civil war on the Boxing Day Tsunami. In contrast to Northern Sri Lanka, which saw wholesale ethnic cleansing, eastern Sri Lanka experienced a gradual and selective process of political and economic exclusion, resulting in the net migration of socioeconomically disadvantaged minority populations towards previously unsettled coastal areas. I quantify these effects, finding that a large majority of homes destroyed in the tsunami did not exist prior to the civil war. Coastal population growth rates were substantially higher than those found in comparable interior areas, as were aggregate rates of socioeconomic vulnerability. Specific instances of displacements and encroachment illustrate how conflict creates incentives for population exposure to environmental risk. The study leverages a unique combination of community surveys, Geographic Information System (GIS) data, public records, official damage reports, ground truth estimates of tsunami impact, and archival evidence of historic population movements. The results are based on the attached paper “Conflict, Coastal Vulnerability, and Resiliency in Tsunami-Affected Communities of Sri Lanka”, in Tsunami Recovery in Sri Lanka: Ethnic and Regional Dimensions, M. Gamburd, D. McGilvray, eds., Taylor and Francis, November 2009. In particular, this paper will expand upon the section entitled “Results of the Community Study: Facts on the Ground” using new community displacement histories and GIS mapping collected in January 2009. -

Symposium Geography 2013 Layout 1

Ashvin Wickramasooriya(1) Analysis of land suitability for development activities in Eastern and Northern coasts of Sri Lanka using spatial technology (1) Faculty of Applied Sciences, South Eastern University of Sri Lanka, Sammanthurai, Sri Lanka. Abstract: Natural resources in North and Eastern experiencing coastal flooding. Also the Eastern and provinces of Sri Lanka were severely affected due to the Northern coasts of Sri Lanka were seriously affected by civil war. This was more significant along the coastal the tsunami which took place in December, 2004. This zone from Mannar to Batticaloa. It has been has created severe environmental and socio-economic establishing more economic development activities in impacts in the region. After this incident, a 100 meter Northern and Eastern provinces after the war. Arial coastal buffer zone has recommended by the Coast photography, Geographical Information Systems (GIS) Conservation Department. However, it was not data and satellite images have proven their importance implemented due to various reasons. Set back limits are as additional tools in identifying prospective areas for also to be considered when identifying land suitability natural resources and also for locating suitable sites for for development activities in the coastal zone. establishing new development activities. In this study integrated approach of remote sensing techniques, The study area Arial photo interpretation and GIS techniques were applied to produce reliable information for The study area covers coastal zones (as defined in identification of most suitable locations for the the Coast Conservation Act No. 57 of 1981) of development activities in the Northern and Eastern Northern and Eastern provinces of Sri Lanka (Figure coastal zones of Sri Lanka.