War Sri Lanka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pattu Central-Chenkalady, Eravur Town

Invitation for Bids (IFB) High Commission of India Grant Number: Col/DC/228/01/2018 Grant Name: Construction of 3,200 Sanitary Units, to enhance the Public health in Batticaloa District of Sri Lanka Estimated Cost Contract Required Bid No Description of Work Excluding Period Grade VAT (SLR in millions) Sri Lankan Bidder: C4 or above/ equivalent Construction of 3,200 (Building) Col/DC/228/01/ Sanitary Units, to enhance the 300 09 months Indian 2018 Public health in Batticaloa District of Sri Lanka Bidder: Class-IV or above/ equivalent (Building) 1. Government of India has approved a Grant for Construction of 3,200 Sanitary Units, to enhance the Public health in Batticaloa District of Sri Lanka based on the proposal submitted by Ministry of Mahaweli, Agriculture, Irrigation and Rural Development, Sri Lanka with the objective of providing a solution for the scarcity of sanitary facilities in Batticaloa District. 2. The Government of India invites sealed bids from eligible and qualified bidders who had experience in construction of Sanitary units to construct 3200 numbers of Sanitary units , to enhance the public health in Koralai Pattu North- Vaharai, Koralai Pattu Central- Valachchenai, Koralai Pattu West-Oddamawadi, Koralai Pattu-Valachchenai, Koralai Pattu South-Kiran, Eravur Pattu Central-Chenkalady, Eravur Town – Eravur, Manmunei North -barricaloa, Manmunei West -Vavunathivu, Manmunei Pattu -Arayampathi, Kattankudy, Manmunei South West-Paddpali, Manmunei South & eruvil Pattu Kaluwanchikudy and Porativ Pattu-Vellaveli under Six packages. The Construction period is 09 Months. 3. Bidding will be conducted through National Competitive Bidding Procedure – Single Stage – Two envelope bidding procedure. (Single stage Two envelop: Bidder has to submit technical and financial bids and duplicate of it separately in four different sealed envelope). -

Beautification and the Embodiment of Authenticity in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2014-2015: Penn Humanities Forum Undergraduate Color Research Fellows 5-2015 Ornamenting Fingernails and Roads: Beautification and the Embodiment of Authenticity in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka Kimberly Kolor University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2015 Part of the Asian History Commons Kolor, Kimberly, "Ornamenting Fingernails and Roads: Beautification and the Embodiment of uthenticityA in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka" (2015). Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2014-2015: Color. 7. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2015/7 This paper was part of the 2014-2015 Penn Humanities Forum on Color. Find out more at http://www.phf.upenn.edu/annual-topics/color. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2015/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ornamenting Fingernails and Roads: Beautification and the Embodiment of Authenticity in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka Abstract In post-conflict Sri Lanka, communal tensions continue ot be negotiated, contested, and remade. Color codes virtually every aspect of daily life in salient local idioms. Scholars rarely focus on the lived visual semiotics of local, everyday exchanges from how women ornament their nails to how communities beautify their open—and sometimes contested—spaces. I draw on my ethnographic data from Eastern Sri Lanka and explore ‘color’ as negotiated through personal and public ornaments and notions of beauty with a material culture focus. I argue for a broad view of ‘public,’ which includes often marginalized and feminized public modalities. This view also explores how beauty and ornament are salient technologies of community and cultural authenticity that build on histories of ethnic imaginaries. -

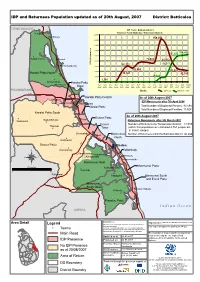

IDP and Returnees Population Updated As of 20Th August, 2007 District: Batticaloa

IDP and Returnees Population updated as of 20th August, 2007 District: Batticaloa TRINCOMALEETRINCOMALEE IDP Trend - Batticaloa District Verugal ! Returnees Trend - Batticaloa / Trincomalee Districts 180,000 Kathiravely ! 159,355 160,000 140,000 120,000 97,405 104,442 ! 100,000 Kaddumurivu ! Vaharai 72,986 80,000 81,312 IDPs/Returnees 60,272 68,971 ! Pannichankerny 60,000 52,685 40,000 51,901 Koralai Pattu North A 1 38,121 42,595 5 20,000 15,524 ! 1,140 Kirimichchai 0 ! Koralai Pattu Marnkerny April May June July Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar April May June July August West 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 POLONNARUWAPOLONNARUWA Months IDP Trend Returnees' Trend A11 Koralai Pattu Central As of 20th August 2007 Vahaneri ! ! IDP Movements after 7th April 2006 Odamavadi Valachchenai ! Koralai Pattu Total Number of Displaced Persons: 42,595 Total Number of Displaced Families: 11,528 Koralai Pattu South As of 20th August 2007 ! ! Eravur Pattu Kudumbimalai Kiran Returnees Movements after 9th March 2007 Vadamunai ! Eravur Number of Returnees to Trincomalee District: 13,589 Tharavai ! Town (within this population an estimated 4,761 people are in transit camps) ! Chenkalady ! Eravur Manmunai Number of Returnees within the Batticaloa District: 90,853 ! A1 North 5 Irralakulam Eravur Pattu A5 Batticaloa ! Pankudavely Kattankudy ! ! Karadiyanaru Vavunathivu ! Kattankudy ! Aythiyamalai ! Arayampathy ® Manmunai West ! Manmunai Pattu Kilometers ! Kokkadicholai Unnichai 020 Pullumalai ! ! Paddipalai -

A Case Study of Kalmunai Municipal Area in Ampara District

Available online at www.worldscientificnews.com WSN 59 (2016) 35-51 EISSN 2392-2192 Emerging challenges of urbanization: a case study of Kalmunai municipal area in Ampara district M. B. Muneera* and M. I. M. Kaleel** Department of Geography, Faculty of Arts and Culture South Eastern University of Sri Lanka, Sri Lanka *,**E-mail address: [email protected] , [email protected] ABSTRACT Urban population refers to people living in urban areas as defined by national statistical offices. It is calculated using World Bank population estimates and urban ratios from the United Nations World Urbanization Prospects. Aggregation of urban and rural population may not add up to total population because of different country coverages. The study based on the Kalmunai MC area and the main objective of this study is to identify the emerging challenges of urbanization in the study area. The study used the methodologies are primary data collection as questionnaire, interview, observation and the secondary data collection and SWOT analysis to made for getting the better result. The study finds that the SWOT analysis process provided a number of results and ideas for future planning. Collecting the results around themes has highlighted the breadth of ideas within KMC. A number of common issues emerged which require immediate action and clearly relate to developing KMC as a resilient urban. However, to generate energy requires heap quantities of plastic wastage and as a result of the process a byproduct of methane will be produced. Nevertheless, this process is not much financially viable as the quantities are limited in Sri Lanka. Control of water pollution is the demand of the day cooperation of the common man, social organizations, natural government and non - governmental organizations; is required for controlling water pollution through different curative measures. -

'ICC Cannot Act Against US, Israel and Sri Lanka'

Vol. 30 No. 208 Tuesday 19th July, 2011, 40 pages Rs. 20 Registered in Sri Lanka as a Newspaper - Late City Edition COULD FATIGUE AND FITCH UPGRADES THE DANGER OF ENGLISH EDUCATION DROWSINESS WHILE SRI LANKA’S MOVING BACK AND POLITICS IN THE DRIVING BE NO 1 SOVEREIGN RATINGS FROM DEVOLUTION NINETIES... 10 11 12 KILLER ON OUR ROADS? Financial Review Ranil demands Select Committee on foul petrol ‘ICC cannot act against BY PIYASENA DISSANAYAKE UNP and Opposition Leader Ranil Wickremesinghe yesterday demanded that a parliamentary select committee US, Israel and Sri Lanka’ be appointed with regard to importing substandard petrol. ead of the International Criminal generally deal only with matters from Wickremesinghe said that he would Court Sang-Hyun Song has said countries that have endorsed the Rome request the government to consider Hthat his court has no jurisdiction Statute. And even then, it can only step the appointment to act on matters from non-signatory in if national legal systems are unwill- of the PSC as States such as Sri Lanka, Israel and the ing or unable to act. an urgent mat- US, a report in The Australian said. “The ICC, under any circumstances, ter and that Song, who runs a tribunal that sits will not and cannot and should not just this sugges- above national legal systems, says his jump over the national boundary of tion request- court complements national systems of sovereign states and stir around the ing the criminal justice. But some critics — par- normally functioning judicial system appointment of ticularly in the US — have described the of a sovereign state,” President Song the relevant ICC as a threat to national sovereignty. -

Post-Tsunami Reconstruction Needs Assessment Northeast Planning and Development Secretariat

Post-Tsunami Reconstruction Needs Assessment for the NorthEast (NENA) Planning and Development Secretariat Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam January 2005 Contents Page 1 Introduction 1 2 Background 2 3 Overview 4 4 Needs Assessment- Sectoral Summaries 7 4.1 Resettlement 7 4.2 Housing 8 4.3 Health 11 4.4 Education 13 4.5 Roads & Bridges 15 4.6 Livelihood, Employment & Micro Finance 17 4.7 Fisheries 18 4.8 Agriculture 21 4.9 Tourism, Culture and Heritage 22 4.10 Environment 23 4.11 Water & Sanitation 25 4.12 Telecommunication 27 4.13 Power 28 4.14 Public Sector Infrastructure 29 4.15 Urban Development 29 4.16 Cooperative Movement 30 4.17 Coastal Protection 30 4.18 Local Government 32 4.19 Disaster Preparedness 33 5.0 Indicative Costs 34 Annex 1 Acronyms 35 Annex 2 Needs Assessment Team 36 Annex 3 Next to Needs 38 Post Tsunami Reconstruction – NorthEast Needs Assessment(NENA) Planning and Development Secretariat/LTTE 2 Post-Tsunami Reconstruction Needs Assessment for the NorthEast 1.0 Introduction The tsunami that struck the coast of Sri Lanka on 26th December 2004 is by far the worst natural disaster the country has experienced in living memory. The Northeast of the island took the greatest and direct impact and the full force of the fierce waves changing the lives of people and the landscape along more than 800 km of the coastline for ever. Within a few devastating minutes, tens of thousands of lives were lost, and billions of dollars worth of infrastructure, equipment and materials were shattered or washed to the seas; thousands more were wounded. -

Batticaloa District

LAND USE PLAN BATTICALOA DISTRICT 2016 Land Use Policy Planning Department No.31 Pathiba Road, Colombo 05. Tel.0112 500338,Fax: 0112368718 1 E-mail: [email protected] Secretary’s Message Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC) made several recommendations for the Northern and Eastern Provinces of Sri Lanka so as to address the issues faced by the people in those areas due to the civil war. The responsibility of implementing some of these recommendations was assigned to the different institutions coming under the purview of the Ministry of Lands i.e. Land Commissioner General Department, Land Settlement Department, Survey General Department and Land Use Policy Planning Department. One of The recommendations made by the LLRC was to prepare Land Use Plans for the Districts in the Northern and Eastern Provinces. This responsibility assigned to the Land Use Policy Planning Department. The task was completed by May 2016. I would like to thank all the National Level Experts, District Secretary and Divisional Secretaries in Batticaloa District and Assistant Director (District Land Use.). Batticaloa and the district staff who assisted in preparing this plan. I also would like to thank Director General of the Land Use Policy Planning Department and the staff at the Head Office their continuous guiding given to complete this important task. I have great pleasure in presenting the Land Use Plan for the Batticaloa district. Dr. I.H.K. Mahanama Secretary, Ministry of Lands 2 Director General’s Message I have great pleasure in presenting the Land Use Plan for the Batticaloa District prepared by the officers of the Land Use Policy Planning Department. -

Divisional Secretariats Contact Details

Divisional Secretariats Contact Details District Divisional Secretariat Divisional Secretary Assistant Divisional Secretary Life Location Telephone Mobile Code Name E-mail Address Telephone Fax Name Telephone Mobile Number Name Number 5-2 Ampara Ampara Addalaichenai [email protected] Addalaichenai 0672277336 0672279213 J Liyakath Ali 0672055336 0778512717 0672277452 Mr.MAC.Ahamed Naseel 0779805066 Ampara Ampara [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Dammarathana Road,Indrasarapura,Ampara 0632223435 0632223004 Mr.H.S.N. De Z.Siriwardana 0632223495 0718010121 063-2222351 Vacant Vacant Ampara Sammanthurai [email protected] Sammanthurai 0672260236 0672261124 Mr. S.L.M. Hanifa 0672260236 0716829843 0672260293 Mr.MM.Aseek 0777123453 Ampara Kalmunai (South) [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Kalmunai 0672229236 0672229380 Mr.M.M.Nazeer 0672229236 0772710361 0672224430 Vacant - Ampara Padiyathalawa [email protected] Divisional Secretariat Padiyathalawa 0632246035 0632246190 R.M.N.Wijayathunga 0632246045 0718480734 0632050856 W.Wimansa Senewirathna 0712508960 Ampara Sainthamarathu [email protected] Main Street Sainthamaruthu 0672221890 0672221890 Mr. I.M.Rikas 0752800852 0672056490 I.M Rikas 0777994493 Ampara Dehiattakandiya [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Dehiattakandiya. 027-2250167 027-2250197 Mr.R.M.N.C.Hemakumara 027-2250177 0701287125 027-2250081 Mr.S.Partheepan 0714314324 Ampara Navithanvelly [email protected] Divisional secretariat, Navithanveli, Amparai 0672224580 0672223256 MR S.RANGANATHAN 0672223256 0776701027 0672056885 MR N.NAVANEETHARAJAH 0777065410 0718430744/0 Ampara Akkaraipattu [email protected] Main Street, Divisional Secretariat- Akkaraipattu 067 22 77 380 067 22 800 41 M.S.Mohmaed Razzan 067 2277236 765527050 - Mrs. A.K. Roshin Thaj 774659595 Ampara Ninthavur Nintavur Main Street, Nintavur 0672250036 0672250036 Mr. T.M.M. -

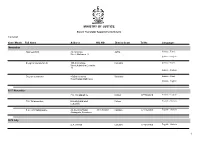

Name List of Sworn Translators in Sri Lanka

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Sworn Translator Appointments Details 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages November Rasheed.H.M. 76,1st Cross Jaffna Sinhala - Tamil Street,Ninthavur 12 Sinhala - English Sivagnanasundaram.S. 109,4/2,Collage Colombo Sinhala - Tamil Street,Kotahena,Colombo 13 Sinhala - English Dreyton senaratna 45,Old kalmunai Baticaloa Sinhala - Tamil Road,Kalladi,Batticaloa Sinhala - English 1977 November P.M. Thilakarathne Chilaw 0777892610 Sinhala - English P.M. Thilakarathne kirimathiyana East, Chilaw English - Sinhala Lunuwilla. S.D. Cyril Sadanayake 26, De silva Road, 331490350V Kalutara 0771926906 English - Sinhala Atabagoda, Panadura 1979 July D.A. vincent Colombo 0776738956 English - Sinhala 1 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 1992 July H.M.D.A. Herath 28, Kolawatta, veyangda 391842205V Gampaha 0332233032 Sinhala - English 2000 June W.A. Somaratna 12, sanasa Square, Gampaha 0332224351 English - Sinhala Gampaha 2004 July kalaichelvi Niranjan 465/1/2, Havelock Road, Colombo English - Tamil Colombo 06 2008 May saroja indrani weeratunga 1E9 ,Jayawardanagama, colombo English - battaramulla Sinhala - 2008 September Saroja Indrani Weeratunga 1/E/9, Jayawadanagama, Colombo Sinhala - English Battaramulla 2011 July P. Maheswaran 41/B, Ammankovil Road, Kalmunai English - Sinhala Kalmunai -2 Tamil - K.O. Nanda Karunanayake 65/2, Church Road, Gampaha 0718433122 Sinhala - English Gampaha 2011 November J.D. Gunarathna "Shantha", Kalutara 0771887585 Sinhala - English Kandawatta,Mulatiyana, Agalawatta. 2 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 2012 January B.P. Eranga Nadeshani Maheshika 35, Sri madhananda 855162954V Panadura 0773188790 English - French Mawatha, Panadura 0773188790 Sinhala - 2013 Khan.C.M.S. -

Page Three Tuesday 26Th May, 2009

The Island Page Three Tuesday 26th May, 2009 ! World View News ! Financial Review ! Leisure Land INSIDE: "308 children lost both parents in war Over 9,000 Tigers to be prosecuted First Lady visits orphans, The Army said 9,100 taken into custody. LTTE suspects would be He also said they would produced before court. be rehabilit ated depending Army spokesman on the nature of crime they Brigadier Udaya have committed. Nanayakkara said that the Among those in custody promises better accommodation suspects include those who were some area leaders. surrendered to the authori - (NP) ties and those who were by Shamindra Ferdinando charge of the Northern The former Commandant asked the children whether they Province told The Island yes - of the elite STF said that p ar- knew the name of the Sri Lankan The government plans to look terday that Mrs. Rajap aksa ent s of some of the children President. A six-year-old boy had af ter 308 children who had lost both had directed Vavuniya now held at the welfare centre promptly said Mahinda Rajapaksa, their p arent s in the war . They are Government Agent Mrs P. M. had been killed while fleeing the police of ficial said. TNA complains not now housed at a welfare centre P. Charles to find a sep arate the LTTE-held area. The Senior DIG said that Mrs established at Menik Farm in the place out side the welfare cen - Responding to our queries, he Rajapaksa had distributed a stock of V avuniya District. tre to house these p arentless said that the children had urgently needed supplies among the allowed to see Moon First lady Mrs. -

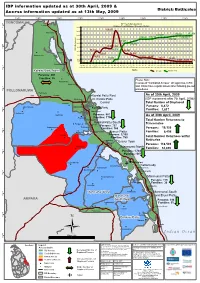

IDP Numbers and Access 30042009 GA Figures

IDP information updated as at 30th April, 2009 & District: Batticaloa Access information updated as at 13th May, 2009 81°15'0"E 81°20'0"E 81°25'0"E 81°30'0"E 81°35'0"E 81°40'0"E 81°45'0"E 81°50'0"E 81°55'0"E TRINCOMALEE (! IDP Trend - Batticaloa District Verugal Returnees Trend - Batticaloa / Trincomalee Districts 8°15'0"N 180,000 159,355 (! 160,000 Kathiravely 136,084 137,659 140,000 127,837 119,527 120,742 136,555 120,000 132,728 97,405 100,000 108,784 72,986 80,000 81,312 8°10'0"N IDPs/Returnees 60,272 68,971 60,000 51,901 (! Vaharai (! 52,685 38,230 Kaddumurivu 40,000 38,121 26,484 24,987 17,600 18,171 12,551 20,000 8,020 1,140 8,543 6,872 (! 0 Panichankerny Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May June July Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2009 2009 2009 2009 8°5'0"N Months IDP Trend Returnees' Trend Koralai Pattu North A 1 Persons: 201 5 Families: 55 (! Please Note: Kirimichchai In areas of "Controlled Access" UN agencies, ICRC Mankerny (! and INGO have regular access after following pre-set procedures. -

Floods Col Road Accessibility in the East 10Jan11

Accessibility in the North and East, Sri Lanka As of 11th January 2011 . I ndian JAFFNA Pallai ! !A9 Pooneryn ! Paranthan ; ! 9°30'0"N ! Killinochchi KILLINOCHCHI !A35 Akkarayankulam Kokkavil ! ! ! Puthukudiyiruppu ! ; ! A9 ! Jeyapuram Thirumurukandy A32 ! ; ; A34 Oddusudan MULAITIVU! !! Tunukkai !A9 Nedunkerny ! 9°0'0"N VAVUNIYA !A14 MANNAR Vavuniya ! A30 ! !A29 A12 A14! Mankulam ! ! ; ! Trincomalee ! Horowpotana TRINCOMALEE !A6 8°30'0"N A9 ! A12 ; ! Kantale ANURADHAPURA ! Anuradhapura A15 Serunuwara ! ; !! A12 ! A9 A15 ! ; ! Vakarai ! A11 ! ! ; Habarana A28 POLONNARUWA PUTTALAM ! A6 A11 ! Polonnaruwa ! 8°0'0"N ! !A10 ! ; Manampitiya A3 ! ; BATTICALOA Batticaloa ! KURUNEGALA !A6 A3 MATALE !A5 ! !A4 ! Kanchanankuda ! Cheddipalayam !A9 A10 Maha Oya ! ! ; A27 ; ! ! Valaichchenai Navithanveli ! 7°30'0"N Padiyathalawa ! Kalmunai ! Chadayathalawa !A5 ! ! Samanthurai A26 ! !A6 !Teldiniya A26 ; !Kandy ! Mahiyangana! ;Ampara ! ! Kundasale ; Inginiyagala AMPARA A1 KANDY T ! ! A3 A1 ! ! KEGALLE ! Bibile !A25 GAMPAHA A21 !A5 ! A5 ! !A4 BADULLA A1 A7 ! ! A25 Colombo A5 ! 7°0'0"N ! NUWARA ELIYA! !A4 A4 COLOMBO ! MONERAGALA A4 ! !A4 !A8 !A18 RATHNAPURA A2 ! A2 KALUTARA ! 6°30'0"N A18 NOTE: ! Following Inaccessible Roads could not be located in the map due to insufficient base data: A17 ! HAMBANTOTA GALLE AMPARA DISTRICT Kanchanankuda - Shaahamam Road MATARA Nainakkaadu - Samanthurai Road !A2 Mallihaitivu - Malwatta Road A2 Walathapitty - Palaveli Road ! 6°0'0"N BATTICALOA DISTRICT Koralaipattu North (Vaharai) DS - Omadiyamadu, Kattumuruppu, Thonithanmadu Koralaipattu West (Oddamavady) DS - Kawattemunai Eravur Town - Eravur DS Road, Ayiyankerny, Meechunhar, Meerakerny, Eravur 06 Manmunai South and Evavur Pattu (Kalavanchikudy) DS - Thethithivu, Kudiyiruppu, Settipalayam, Pottani, Eruvil Koramadu 79°0'0"E 79°30'0"E 80°0'0"E 80°30'0"E 81°0'0"E 81°30'0"E 82°0'0"E Map data source: Disaster Management Centre of Sri Lanka (DMC) Legend UNDSS - Sri Lanka, DMC - Sri Lanka Ministry of Disaster Management ! XX Road Name Disaster Event Disclaimers: BMICH, Baudhaloka Mawatha, Colombo 7.