Tsunami Response in Sri Lanka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beautification and the Embodiment of Authenticity in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2014-2015: Penn Humanities Forum Undergraduate Color Research Fellows 5-2015 Ornamenting Fingernails and Roads: Beautification and the Embodiment of Authenticity in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka Kimberly Kolor University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2015 Part of the Asian History Commons Kolor, Kimberly, "Ornamenting Fingernails and Roads: Beautification and the Embodiment of uthenticityA in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka" (2015). Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2014-2015: Color. 7. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2015/7 This paper was part of the 2014-2015 Penn Humanities Forum on Color. Find out more at http://www.phf.upenn.edu/annual-topics/color. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2015/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ornamenting Fingernails and Roads: Beautification and the Embodiment of Authenticity in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka Abstract In post-conflict Sri Lanka, communal tensions continue ot be negotiated, contested, and remade. Color codes virtually every aspect of daily life in salient local idioms. Scholars rarely focus on the lived visual semiotics of local, everyday exchanges from how women ornament their nails to how communities beautify their open—and sometimes contested—spaces. I draw on my ethnographic data from Eastern Sri Lanka and explore ‘color’ as negotiated through personal and public ornaments and notions of beauty with a material culture focus. I argue for a broad view of ‘public,’ which includes often marginalized and feminized public modalities. This view also explores how beauty and ornament are salient technologies of community and cultural authenticity that build on histories of ethnic imaginaries. -

A Case Study of Kalmunai Municipal Area in Ampara District

Available online at www.worldscientificnews.com WSN 59 (2016) 35-51 EISSN 2392-2192 Emerging challenges of urbanization: a case study of Kalmunai municipal area in Ampara district M. B. Muneera* and M. I. M. Kaleel** Department of Geography, Faculty of Arts and Culture South Eastern University of Sri Lanka, Sri Lanka *,**E-mail address: [email protected] , [email protected] ABSTRACT Urban population refers to people living in urban areas as defined by national statistical offices. It is calculated using World Bank population estimates and urban ratios from the United Nations World Urbanization Prospects. Aggregation of urban and rural population may not add up to total population because of different country coverages. The study based on the Kalmunai MC area and the main objective of this study is to identify the emerging challenges of urbanization in the study area. The study used the methodologies are primary data collection as questionnaire, interview, observation and the secondary data collection and SWOT analysis to made for getting the better result. The study finds that the SWOT analysis process provided a number of results and ideas for future planning. Collecting the results around themes has highlighted the breadth of ideas within KMC. A number of common issues emerged which require immediate action and clearly relate to developing KMC as a resilient urban. However, to generate energy requires heap quantities of plastic wastage and as a result of the process a byproduct of methane will be produced. Nevertheless, this process is not much financially viable as the quantities are limited in Sri Lanka. Control of water pollution is the demand of the day cooperation of the common man, social organizations, natural government and non - governmental organizations; is required for controlling water pollution through different curative measures. -

Post-Tsunami Reconstruction Needs Assessment Northeast Planning and Development Secretariat

Post-Tsunami Reconstruction Needs Assessment for the NorthEast (NENA) Planning and Development Secretariat Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam January 2005 Contents Page 1 Introduction 1 2 Background 2 3 Overview 4 4 Needs Assessment- Sectoral Summaries 7 4.1 Resettlement 7 4.2 Housing 8 4.3 Health 11 4.4 Education 13 4.5 Roads & Bridges 15 4.6 Livelihood, Employment & Micro Finance 17 4.7 Fisheries 18 4.8 Agriculture 21 4.9 Tourism, Culture and Heritage 22 4.10 Environment 23 4.11 Water & Sanitation 25 4.12 Telecommunication 27 4.13 Power 28 4.14 Public Sector Infrastructure 29 4.15 Urban Development 29 4.16 Cooperative Movement 30 4.17 Coastal Protection 30 4.18 Local Government 32 4.19 Disaster Preparedness 33 5.0 Indicative Costs 34 Annex 1 Acronyms 35 Annex 2 Needs Assessment Team 36 Annex 3 Next to Needs 38 Post Tsunami Reconstruction – NorthEast Needs Assessment(NENA) Planning and Development Secretariat/LTTE 2 Post-Tsunami Reconstruction Needs Assessment for the NorthEast 1.0 Introduction The tsunami that struck the coast of Sri Lanka on 26th December 2004 is by far the worst natural disaster the country has experienced in living memory. The Northeast of the island took the greatest and direct impact and the full force of the fierce waves changing the lives of people and the landscape along more than 800 km of the coastline for ever. Within a few devastating minutes, tens of thousands of lives were lost, and billions of dollars worth of infrastructure, equipment and materials were shattered or washed to the seas; thousands more were wounded. -

Divisional Secretariats Contact Details

Divisional Secretariats Contact Details District Divisional Secretariat Divisional Secretary Assistant Divisional Secretary Life Location Telephone Mobile Code Name E-mail Address Telephone Fax Name Telephone Mobile Number Name Number 5-2 Ampara Ampara Addalaichenai [email protected] Addalaichenai 0672277336 0672279213 J Liyakath Ali 0672055336 0778512717 0672277452 Mr.MAC.Ahamed Naseel 0779805066 Ampara Ampara [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Dammarathana Road,Indrasarapura,Ampara 0632223435 0632223004 Mr.H.S.N. De Z.Siriwardana 0632223495 0718010121 063-2222351 Vacant Vacant Ampara Sammanthurai [email protected] Sammanthurai 0672260236 0672261124 Mr. S.L.M. Hanifa 0672260236 0716829843 0672260293 Mr.MM.Aseek 0777123453 Ampara Kalmunai (South) [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Kalmunai 0672229236 0672229380 Mr.M.M.Nazeer 0672229236 0772710361 0672224430 Vacant - Ampara Padiyathalawa [email protected] Divisional Secretariat Padiyathalawa 0632246035 0632246190 R.M.N.Wijayathunga 0632246045 0718480734 0632050856 W.Wimansa Senewirathna 0712508960 Ampara Sainthamarathu [email protected] Main Street Sainthamaruthu 0672221890 0672221890 Mr. I.M.Rikas 0752800852 0672056490 I.M Rikas 0777994493 Ampara Dehiattakandiya [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Dehiattakandiya. 027-2250167 027-2250197 Mr.R.M.N.C.Hemakumara 027-2250177 0701287125 027-2250081 Mr.S.Partheepan 0714314324 Ampara Navithanvelly [email protected] Divisional secretariat, Navithanveli, Amparai 0672224580 0672223256 MR S.RANGANATHAN 0672223256 0776701027 0672056885 MR N.NAVANEETHARAJAH 0777065410 0718430744/0 Ampara Akkaraipattu [email protected] Main Street, Divisional Secretariat- Akkaraipattu 067 22 77 380 067 22 800 41 M.S.Mohmaed Razzan 067 2277236 765527050 - Mrs. A.K. Roshin Thaj 774659595 Ampara Ninthavur Nintavur Main Street, Nintavur 0672250036 0672250036 Mr. T.M.M. -

Name List of Sworn Translators in Sri Lanka

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Sworn Translator Appointments Details 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages November Rasheed.H.M. 76,1st Cross Jaffna Sinhala - Tamil Street,Ninthavur 12 Sinhala - English Sivagnanasundaram.S. 109,4/2,Collage Colombo Sinhala - Tamil Street,Kotahena,Colombo 13 Sinhala - English Dreyton senaratna 45,Old kalmunai Baticaloa Sinhala - Tamil Road,Kalladi,Batticaloa Sinhala - English 1977 November P.M. Thilakarathne Chilaw 0777892610 Sinhala - English P.M. Thilakarathne kirimathiyana East, Chilaw English - Sinhala Lunuwilla. S.D. Cyril Sadanayake 26, De silva Road, 331490350V Kalutara 0771926906 English - Sinhala Atabagoda, Panadura 1979 July D.A. vincent Colombo 0776738956 English - Sinhala 1 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 1992 July H.M.D.A. Herath 28, Kolawatta, veyangda 391842205V Gampaha 0332233032 Sinhala - English 2000 June W.A. Somaratna 12, sanasa Square, Gampaha 0332224351 English - Sinhala Gampaha 2004 July kalaichelvi Niranjan 465/1/2, Havelock Road, Colombo English - Tamil Colombo 06 2008 May saroja indrani weeratunga 1E9 ,Jayawardanagama, colombo English - battaramulla Sinhala - 2008 September Saroja Indrani Weeratunga 1/E/9, Jayawadanagama, Colombo Sinhala - English Battaramulla 2011 July P. Maheswaran 41/B, Ammankovil Road, Kalmunai English - Sinhala Kalmunai -2 Tamil - K.O. Nanda Karunanayake 65/2, Church Road, Gampaha 0718433122 Sinhala - English Gampaha 2011 November J.D. Gunarathna "Shantha", Kalutara 0771887585 Sinhala - English Kandawatta,Mulatiyana, Agalawatta. 2 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 2012 January B.P. Eranga Nadeshani Maheshika 35, Sri madhananda 855162954V Panadura 0773188790 English - French Mawatha, Panadura 0773188790 Sinhala - 2013 Khan.C.M.S. -

Provincial Roads Project

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: 48445 - LK PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A Public Disclosure Authorized PROPOSED.CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 66.1 MILLION (US$105 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA FOR A Public Disclosure Authorized PROVINCIAL ROADS PROJECT November 11,2009 Sustainable Development Unit Sri Lanka Country Management Unit South Asia Region This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the Public Disclosure Authorized performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective October 3 1,2009) Currency Unit = Rupees 114.25Rupees = US$1 1.58989US$ = SDR 1 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 ADB Asian Development Bank MLGPC Ministry of Local Government and Provincial Councils AGAOA Association of Government MOT Ministry of Transport Accounts Organizations of Asia AG Auditor General MOFP Ministry of Finance and Planning BP Bank Procedure NCP North Central Province CAS Country Assistance Strategy NEA National Environmental Act CEA Central Environmental NPRDD Northern Provincial Road Authority Development Department CFAA Country Financial NPV Net Project Value EPRDD Eastern Provincial Road PMR Project Management Report Development Department EAMF Environmental Assessment PDO Project Development Objective and Management Framework FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Environmental Management PRP I EMPs I Plans Economic Internal rate of RDA Road Development Authority I 1 Return FM Financial Management RFA Reimbursable Forei n Aid FRs Financial Regulations ROW Right Of Way I ~ 1 GAAP I Governance and RIJ Resettlement Plan Accountability Action Plan GOSL Government of Sri Lanka RSAP HDM4 Highway Design and SEPSA Management Version 4 HIV/AIDS Human Immunodeficiency SBD Virus/ Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome . -

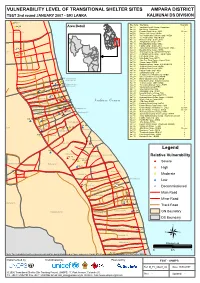

VULNERABILITY LEVEL of TRANSITIONAL SHELTER SITES AMPARA DISTRICT TSST 2Nd Round JANUARY 2007 - SRI LANKA KALMUNAI DS DIVISION

VULNERABILITY LEVEL OF TRANSITIONAL SHELTER SITES AMPARA DISTRICT TSST 2nd round JANUARY 2007 - SRI LANKA KALMUNAI DS DIVISION *#Kal_16 Site Code Site Name Total Vul. Kal_02 *# Area Detail Kal_01 Varathan RiceMill Camp - Samaritans 1 Kal_02 Bar Camp - Samaritan 1 Periyaneelavanai 01B Kal_04 Ponniah Road Camp - WDC Decom Kal_06 Vishnu Kovil Camp - NHDA 1 Kal_07 VC Road Muslim Division Camp - NHDA 1 Kal_08 V.C.Road Camp - WDC/NHDA 1 Kal_12 Moossa Camp - Sewa Lanka 2 Kal_15 Sanganthurai Camp - JVP 1 Kal_16 Masjidul Aqbar Camp - WDC 1 Kal_17 Hudha Camp - Sewa Lanka 1 Kal_04 Kal_18 Aqbar Jummah Mosque Road Camp - WDC 3 0* Kal_19 Masjidul Aqbar Camp - NHDA 2 ai 01A Kal_20 S.M.Road Camp - UNHCR/EHED/FCE 2 *#Kal_01 Kal_21 Al-Manar Central Camp - FORUT/WDC 1 Kal_22 Hijra Road Camp - JVP 2 Kal_23 Hijra Road Camp -MFCD 2 Kal_24 Sam Sum Road Camp - Islamic Relief 1 Kal_25 Shums Camp - EHED 2 Kal_26 Maqbooliya Lane Camp - EHED/UNHCR 2 Kal_27 Al-Minah Road Camp - NHDA 1 Kal_28 Al-Minan Road Camp - WDC 1 Kal_30 Hajiyar Road Camp - WDC 1 Kal_31 Sahanthura Camp - JVP 2 Kal_33 Sellappa Cross Road Camp - EHED 1 Kal_34 Valluvar(AI-Minan Camp)-EHED 2 Kal_17 Kal_12 Periyaneelavanai Kal_35 Maha Vidyalaya Camp - EHED 2 *# Muslim Sec.02 Kal_07 *# Kal_37 Khali Kovil Camp - NHDA/Sevalanka 2 *# *# *# Kal_38 Thathan Camp - MSF / EHED 1 Kal_06 Periyaneelavanai Kal_39 Thiroufathy Amman Camp - EHED 1 Kal_08 Muslim Sec.01 Kal_68 Kal_40 Vipulananda Camp-EHED 1 Periyaneelavanai 02 Kal_69 Kal_20 Kal_41 Visuvasikal Illam Camp 1 *# Kal_15 *# Kal_19 *# Kal_27*# *# *# Kal_43 -

Club Health Assessment MBR0087

Club Health Assessment for District 306 C2 through January 2021 Status Membership Reports Finance LCIF Current YTD YTD YTD YTD Member Avg. length Months Yrs. Since Months Donations Member Members Members Net Net Count 12 of service Since Last President Vice Since Last for current Club Club Charter Count Added Dropped Growth Growth% Months for dropped Last Officer Rotation President Activity Account Fiscal Number Name Date Ago members MMR *** Report Reported Report *** Balance Year **** Number of times If below If net loss If no When Number Notes the If no report on status quo 15 is greater report in 3 more than of officers thatin 12 months within last members than 20% months one year repeat do not haveappears in two years appears appears appears in appears in terms an active red Clubs less than two years old 144565 Colombo Ananda Alumni 12/29/2020 Newly 20 20 0 20 100.00% 0 0 N N/R Chartered 144601 Colombo Capital 12/29/2020 Newly 26 26 0 26 100.00% 0 0 N SC N/R Chartered 144533 Colombo Knights 12/29/2020 Newly 21 21 0 21 100.00% 0 0 N N/R Chartered P,T,M,SC 139377 Colombo National Tourist Guide 09/11/2019 Active 19 6 14 -8 -29.63% 23 1 0 N 7 lecturer 139376 Godagama Sunrise 09/11/2019 Active(1) 15 0 1 -1 -6.25% 19 1 0 2 R M,MC,SC N/A 137878 Kottawa Ladies Dignity 04/08/2019 Active(1) 12 3 4 -1 -7.69% 21 2 0 None N P 11 143788 Nugegoda 2020 Stars 12/14/2020 Newly 21 21 0 21 100.00% 0 0 N SC N/R Chartered Clubs more than two years old SC 98009 AKKARAIPATTU 11/15/2006 Active 15 0 0 0 0.00% 15 0 R 9 Exc Award (06/30/2016) SC 61386 BADULLA -

JNSF March 2010 SC 1

J.Natn.Sci.Foundation Sri Lanka 2010 38 (1): 59-64 SHORT COMMUNICATION Wave record and flow regimes of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami in Sri Lanka Ananda Gunatilaka 10, Thumbovila, Piliyandala. Submitted: 10 May 2009; Accepted: 17 July 2009 Abstract: Tsunami waves that impacted upon the coastline (including Sri Lanka) recorded water level variations over of Sri Lanka on the 26 th December 2004 were investigated several days 2. The shoaling waves generated a complex with respect to their hydrodynamic interactions and resulting flow regime, with extensive inundation of the low coastal complex flow regimes. Field surveys showed that a large island plain and deposited a sand-sheet 2-22 cm thick over an with a narrow and steep continental shelf was subjected to area of ~120-140 km 2. The lost and unaccounted for lives destructive waves, which swept around a 900 km swathe of exceeded 39,000 in Sri Lanka, with over half a million coastline from the eastern seaboard (facing the seismic source in Sumatra) to the western or shadow side with comparable people being displaced. Property and infrastructure magnitude and intensity. Waves impacted the coastline directly damage was estimated at ~ US$ 2 billion. Around (orthogonally) and were also reflected and refracted according 4 million people inhabit a 1 km wide coastal zone. to the geomorphology of the coastline. Three waves of different magnitude and competence inundated the coastal plain as far as An international tsunami survey team (ITST) made 2 km inland in about four hours. The maximum wave heights and a rapid four day survey of selected coastal areas within run-up elevations exceeded 12 m. -

Ampara for the Year 2017

1 ලාක කාය සාධන ලාතාල හා 燒귔 tUlhe;j nrayhw;W mwpf;ifAk; fzf;fwpf;ifAk; ANNUAL PERFORMANCE REPORT & ACCOUNTS 2017 뷒ස්ත්රික්ලේකමකකායායඅපාර khtl;l nrayfk; - mk;ghiw DISTRICT SECRETARIAT AMPARA 2 Subject Page No. 01. District Administration 1.1 Massage of the District Secretary 06 1.2 Mission,Vision,Statement, Objectives & Activities of the District Secretariat 08 1.3 Historical Background of Ampara District 09 1.4 District Secretariat and Attached Institution 11 1.5 Grama Niladhary Divisions and Organization chart of the District Secretariat 12 1.6 Duty and Responsible of the Administration Branch of the District Secretariat 15 1.7 Cadre Details of the District Secretariat & Divisional Secretariats 16 1.8 Details of Government Quarters assigned to the District Secretariat 17 1.9 Details of Charges for Circuit Bungalow 18 1.10 Details of Income earned from Circuit Bungalow 19 02 Populations 2.1 Total Population of Ampara District by DS Division on Sex Ratio 21 2.2 Percentage distribution of Population by ethnic group and D.S Division -2016 22 03. Agriculture 3.1 Paddy Cultivation 24 3.2 OFC and Other Highland Crops Cultivation 25 3.3 Fruit Crops Cultivation 26 04. Education 4.1 School Type and Medium-2017 28 4.2 National School Type and Medium-2017 29 4.3 Provincial School Type and Medium-2017 30 4.4 Education Zone and Education Division-2017 31 3 05. Development 5.1 District Secretariat development Works-(270) 2017 34 5.2 Ministry of National Policies &Economic Affairs (104) (DCB) 35 5.3 Rural Infrastructure Development Programme – 2017 36 5.4 Rural Sports Ground Development - 2017 37 5.5 Ministry of Resettlement Works-(145) 2017 39 5.6 District Development Programmes implemented by 41 District Secretariats Ampara - 2017 5.7 Activities of District Samurdhi Unit 42 5.8. -

First Report of Genus Chroococcidiopsis (Cyanobacteria) from Sri Lanka: a Potential Threat to Human Health

J.Natn.Sci.Foundation Sri Lanka 2013 41 (1): 65-68 RESEARCH NOTE First report of genus Chroococcidiopsis (cyanobacteria) from Sri Lanka: a potential threat to human health D.N. Magana-Arachchi * and R.P. Wanigatunge Institute of Fundamental Studies, Hantana Road, Kandy. Revised: 24 October 2012 ; Accepted: 19 November 2012 Keywords: Chroococcidiopsis , cyanobacteria, 16S rRNA Members of the genus Chroococcidiopsis are very gene. primitive, photosynthetic, coccoid cyanobacteria and they have the capability to survive under high radiation, Cyanobacteria (Cyanophytes, Cyanoprokaryotes) are extreme temperatures, osmotic stress and extreme pH a large group of photosynthetic bacteria and one of values. Genus Chroococcidiopsis have been found in the most fascinating groups of organisms on the earth. freshwater, marine, hypersaline environments (Dor et They show a considerable morphological diversity. al ., 1991), hot springs, nitrate caves (Geitler, 1933; Microscopy is the classical method of cyanobacterial Friedmann, 1962), hot and cold deserts, airspaces of LGHQWL¿FDWLRQDQGFRPPXQLW\DVVHVVPHQW,WLVGLI¿FXOW porous rocks from Antarctic valleys and in several to classify cyanobacteria into accurate taxonomic groups lichens as cyanobionts (Büdel et al., 2000). VLQFHF\DQREDFWHULDOPRUSKRORJ\YDULHVVLJQL¿FDQWO\LQ UHVSRQVH WR ÀXFWXDWLRQV RI HQYLURQPHQWDO FRQGLWLRQV While investigating the biodiversity of cyanobacteria Consequently, molecular biological techniques have in different parts of Sri Lanka, Chroococcidiopsis become a popular tool for phylogenetic -

An Ecological Risk Assessment of Sediments in a Developing Environment—Batticaloa Lagoon, Sri Lanka

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article An Ecological Risk Assessment of Sediments in a Developing Environment—Batticaloa Lagoon, Sri Lanka Madurya Adikaram 1,* , Amarasooriya Pitawala 2, Hiroaki Ishiga 3, Daham Jayawardana 4 and Carla M. Eichler 5 1 Department of Physical Sciences, Faculty of Applied Sciences, South Eastern University, Sammanthurai 32200, Sri Lanka 2 Department of Geology, Faculty of Science, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya 20400, Sri Lanka; [email protected] 3 Department of Geosciences, Graduate School of Science and Engineering, Shimane University, Shimane 690-8501, Japan; [email protected] 4 Department of Forestry and Environmental Science, Sri Jayawardhanapura University, Gangodawila, Nugegoda 10250, Sri Lanka; [email protected] 5 Department of Geosciences, Texas Tech University, Science Building 307, 1053 Main St, Lubbock, TX 79401, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +94-718-318-140 Abstract: The land-sea interface is considered as a threatening environment due to anthropogenic development activities. Unplanned developments can cause effects on important ecosystems, wa- ter and human health as well. In this study, the influence of rapid regional development on the accumulation of trace elements to the sediments of an important ecosystem, Batticaloa lagoon, Sri Lanka was examined. Surface sediment pollution status and ecological risk was compared with that of the recent sedimentary history of about 1 m depth. Sediment core samples were collected and analyzed for grain size, organic matter and carbonate contents and trace elements (As, Pb, Zn, Cu, Ni and Cr) by the X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) technique. The chemical results of core samples and recently published data of surface sediments of the same project were evaluated by pollution load index (PLI), potential ecological risk index (PERI) and sediment quality guidelines (SQG).